CHAPTER 39 Surgical Management of Axial Pain

Epidemiology and Natural History

Having an appreciation of the factors that affect the health of the population is important in understanding the individual who seeks treatment. A study of adolescents concerning the prevalence of musculoskeletal pain in Finland revealed only approximately 25% of 18-year-old girls and about 50% of boys with no report of neck or arm pain in the last 6 months.1 Of these self-reports to questions about musculoskeletal pain, only a small single-digit percentage sought medical consultation. The author’s of the Finnish study note that this prevalence is high, but that the relevance of such reported pain is questionable without knowing the magnitude of the pain-related disability.

It is known from population-based sectional survey studies that numerous individuals complain of acute or chronic neck pain.2–4 The overall prevalence of “troubles or neck pain” was 34.4% in a Norwegian registry, with 13.8% of that group reporting chronic neck pain of greater than 6 months’ duration.2 Similar numbers were reported by Makela and colleagues4 in a study of chronic neck pain in Finland. In an article on the Saskatchewan population published in 2000, Cotes and colleagues3 found that 54% of 1131 respondents had experienced neck pain in the previous 6 months. Of that group, 5% reported that they were “highly disabled” because of neck pain. A comprehensive review by Manchikanti and colleagues5 suggested that the prevalence of people with high pain intensity with disability owing to neck pain is 15%, with 25% to 60% having chronic symptoms 1 year or longer after the initial episode. Complaints of neck pain in the population are common, if the question is asked, but only a small percentage are plagued enough to seek care; if they do seek care, a fair number of people have persistent pain that may lead to surgical consultation.

Why Understanding the Natural History of a Condition Is Crucial

In patients with apparent mechanical axial pain resulting from a degenerative condition, observation with nonoperative recommendations would be appropriate for most patients. When reviewing natural history studies, there is the inherent selection bias of individuals who sought care because of the severity of their symptoms. Many individuals who report pain on population surveys of prevalence of symptoms would not seek out care. In a population questionnaire study, Badcock and colleagues6 found that 11.7% of questionnaire responders had neck pain and that 21% sought general practice consultation; 77% of responders seeking consultation had persistent symptoms, which was a greater percentage of persistent disability than among responders who did not seek out consultation.

Gore and colleagues7 published a classic series on the long-term follow-up of patients who present with neck pain. With a minimum 10-year follow-up, clinical and radiographic data were reported on 205 patients with a chief complaint of neck pain. Of that group, “79% had a decrease in pain, and 43% were pain free; however, 32% had moderate to severe pain.”7 The investigators noted that a specific injury and severity of the initial pain were suggestive of having an unsatisfactory long-term outcome.

In an earlier edition of this text, Rothman8 stated that “it does not appear that cervical disc degeneration is a brief, self limiting disorder, but rather a chronic disease, productive of significant pain and incapacity over an extended period of time.” DePalma and Subin9 reported in 1965 that among patients treated nonoperatively for “cervical syndrome,” only 45% of those presenting for treatment with a chief complaint of neck pain or neck with arm pain had a long-term satisfactory outcome. In a series of the results of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) for cervical spondylosis, DePalma and colleagues10 reported that 21% had complete relief at 3 months with nonoperative care, whereas 22% had no relief. In a 5-year follow-up study of patients presenting with significant complaints of pain secondary to cervical disc degeneration, Rothman and Rashbaum11 noted that 23% remained partially or totally disabled.

When one looks at more recent publications, these classic studies are mirrored. Walker and colleagues12 performed a randomized clinical trial of manual physical therapy and exercise compared with minimal intervention in 94 patients presenting with neck pain, with or without arm pain. At 1-year follow-up, 62% of patients perceived success with treatment, which means that 38% had persistent symptoms, and only 32% in the minimum intervention group perceived treatment success, which means that 68% had persistent complaints. A classic study of the natural history of cervical spondylosis by Lees and Turner13 and a review in the 1980s showed that patients presenting with cervical radiculopathy do not typically progress to myelopathy. Two thirds of patients treated with nonoperative care had consistent complaints of pain, although not severe in all.

Etiology

In relation to trauma, numerous patients are seen who have a rear-end mechanism motor vehicle accident as the etiology for their complaint of neck pain—that is, a “whiplash” injury. The Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders produced a monograph concluding that patients should be reassured that whiplash-associated disorder is “almost always” self-limited and that it “rarely results in permanent harm.”14 In rebuttal, Freeman and colleagues15 performed a methodologic critique of the literature and stated, “there is no epidemiologic or scientific basis in the literature for the following statement: whiplash injuries do not lead to chronic pain, rear end impact collisions that do not result in vehicle damage are unlikely to cause injury, and whiplash trauma is biomechanically comparable with common movements of daily living.”

Although currently there is an emphasis on performing better designed studies of early nonoperative management of whiplash-associated injuries, a rich history of observational studies does not exist.16 McNab17 reported on 266 patients, out of an original group of 575 patients with soft tissue neck injuries, who were 2 years after settlement of court issues, so as to minimize the bias of legal secondary gain. Of these 266 patients, 145 were available for review, with 121 reporting persistent pain; at minimum, 45% (121 of 266) had symptoms 2 years after court settlement per their injury.17,18 In a similar type of study, Hohl19 noted that of 146 patients who had no pr-existing degenerative condition, 45% had persistent pain 5 years after injury, and in a continuing series from the United Kingdom following patients with whiplash injuries, 66% were noted to have complaints of pain at 2 years after injury, with 10-year follow-up revealing reports of “intrusive pain” and 28% “severe” pain in 12%.20–22 In a prospective Scandinavian series of 93 patients, Hildingsson and Toolanen23 noted complete recovery in 42%, mild discomfort in 14%, and significant residual complaints in 44%. Likewise, Jonsson and colleagues24 reported that 28% (14 of 50) of patients with whiplash distortions had persistent symptoms. Although changing from a tort to no-fault system, to eliminate compensation for pain and suffering, decreases the percentages with whiplash injury from a motor vehicle accident, Cassidy and colleagues25 wrote that the prognosis for individuals with whiplash injury is affected by “… Intrinsic factors such as age, sex, and initial intensity of the pain.” In a series on early aggressive care for patients with whiplash injury, Cote and colleagues26 noted that their “results add to the body of evidence suggesting that early aggressive treatment of whiplash injuries does not promote faster recovery.”

When seeing a patient with whiplash-associated injuries, it would seem that clinicians may counsel them that “usually” or “more often” their pain will subside as they heal themselves and that only a “low percentage” will have long-term permanent damage. This counseling is in contrast, however, to the wording that the patient “almost always” gets better and “rarely has permanent harm” as suggested by the Quebec Task Force.14 In perhaps 10% to 20% of an original whiplash injury population, a surgeon would benefit a patient by proceeding with a diagnostic evaluation to objectify specific anatomic pathologies that may be remedied with open or minimally invasive surgical intervention.

Patient Evaluation

History

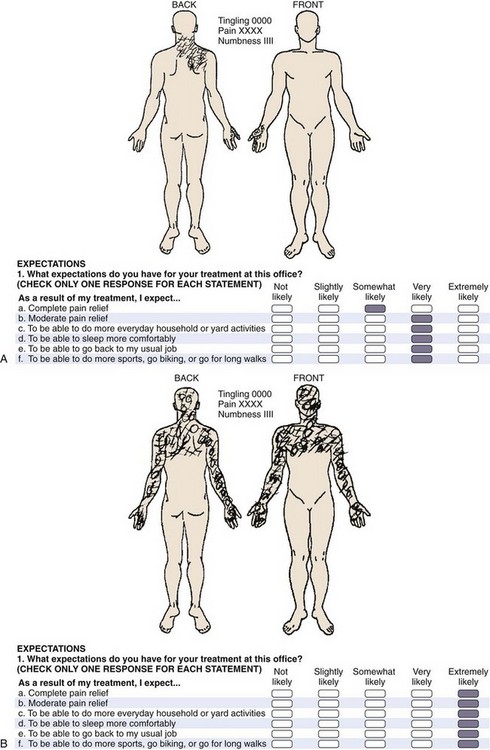

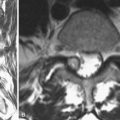

One needs to assess the onset (traumatic vs. nontraumatic, acute vs. insidious) and the location of the pain and whether it is local, referred (basioccipital, upper trapezial, or periscapular), or radicular into the arm. A specific assessment of the component that is related to neck pain versus arm pain is crucial (e.g., 80% neck pain and headaches vs. 20% arm pain). Neurologic symptoms of numbness, tingling, weakness, sphincter dysfunction, or ataxia are sought. The pattern of pain is important. Is the pain worse with flexion activities? Does it increase as the day goes on and respond to rest? This finding would suggest a discogenic source, which is a common presenting condition. Unilateral radiation to the upper trapezial and interscapular region that restricts turning the head to that side suggests a radicular component. A history of a known diagnosis of cancer or infection is noted, and constitutional symptoms of night pain, rest pain, fever, and weight loss are reviewed. The social history documents the presence or absence of litigation, workers’ compensation activity, and use of tobacco. The family history may suggest a genetic predisposition. The patient’s self-reported documentation should be reviewed (e.g., pain diagrams, visual analog scale [VAS], self-reported functional scale, SF-36, patient expectations). The pain diagram can be very useful in the assessment of axial mechanical pain with the continuum of those suggesting an anatomic source that makes one think more of a surgical option versus those suggesting a nonorganic source where one thinks less of invasive testing to determine a surgical option (Fig. 39–1A).

The psychosocial evaluation is critical. True malingerers are rare but do exist.27 Symptom amplification, drug-seeking behavior, work-related litigation, motor vehicle accident litigation, clinical depression, and frank psychiatric dysfunction all can have an impact on the patient’s self-perceived outcome as it relates to the success of elective surgical intervention for axial neck pain. A patient with a nonorganic diagram (Fig. 39–1B) who presents with a history of daily intake of high doses of narcotics, with active litigation, and who smokes two packs of cigarettes per day would suggest delay in surgical management. In a published series in 2002 on axial neck pain, the author and colleagues were unable to correlate a negative outcome with the presence or absence of litigation or cigarette smoking.28 A series from Cleveland documented that of patients who took daily narcotics for greater than 6 months, 51% (24 of 47) reported good to excellent outcome, and 32% (15 of 47) had a poor result.29 These findings contrast with patients without chronic narcotic use having 86% (38 of 44) good to excellent outcomes and no patients with a poor outcome.29

Radiographic Evaluation

The outpatient evaluation should be sequential. A history and physical examination are followed by plain radiographs before magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). The author routinely obtains an anteroposterior, lateral, and flexion-extension lateral radiographic series. Open-mouth or oblique views do not need to be routinely obtained. These radiographs are ordered for destructive processes that indicate tumor or infection (and the history of axial neck pain did not suggest such) or for the presence of foraminal stenosis, for which one would typically obtain advanced imaging. The presence of spondylosis, as evidenced by loss of disc height, subchondral sclerosis, cyst formation, or osteophyte formation, and the presence of listhesis with any dynamic component to suggest mechanical instability are documented. Using these factors, the author and colleagues have reported on a quantitive radiographic scoring system, which yields a cervical degenerative index.30,31 This objective assessment may be useful to follow patients regarding the progression of disease or patients who have had surgery regarding the development of adjacent segment degeneration. The index is an expansion of Gore’s assessment, and a higher score indicates more radiographic pathology at more levels. In a young patient with multilevel spondylosis, one would tend to encourage nonoperative treatment. The presence of spondylosis on radiographs is nonspecific and does exist in asymptomatic individuals, but the review of plain radiographs is still quite useful.32,33

Advanced Imaging

In a patient who has dominant axial mechanical neck pain, who has failed 12 months of nonoperative care, including an active rehabilitative component, in whom a psychosocial contraindication does not exist, and who perceives his or her pain to be so severe to consider surgical options, the next step is MRI. If MRI is contraindicated (e.g., pacemaker or metal fragment in the eye), a CT myelogram is done. The scan is reviewed for tumor, infection, or neurologic compression, but in this subgroup of axial pain, a special note is made of disc morphology, annular tears, small central herniations, listhesis with facet arthrosis, and the number of levels of involvement. In a patient who has a clinical correlation of C6 pattern, such as the previously mentioned patient with 90% neck pain and 10% arm pain, who has a central to right small C5-6 herniated nucleus pulposus with pristine-appearing C4-5 and C6-7 levels, no additional testing may be necessary. A C5-6 ACDF may be an option, but in this group of patients with axial pain, this type of clear-cut scenario is uncommon, and additional testing is more often advised. Also, numerous asymptomatic individuals have degenerative change on their studies, and the presence of these changes increases with age.34–37

The debate on the rational basis to use discography continues.38,39 Nordin and colleagues,38 citing a critical review of the literature, stated that “no evidence supports using provocative discography, anesthetic facet, or medial branch blocks in evaluating neck pain.” Manchikanti and colleagues39 reported on a comprehensive search of the literature, using a modified Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ) level of evidence evaluation, and documented that “cervical discography plays a significant role in selecting surgical candidates in improving outcomes, despite concerns regarding the false positive rate, lack of standardization, and assorted potential confounding factors.” Because of this discrepancy, perhaps related to the bias of the groups, an expanded review of discography is planned. In the author’s experience, discography is a useful clinical tool.

Advanced Invasive Diagnostics

Discography as a diagnostic tool is controversial. If one wishes to consider surgical options in patients with axial neck pain, of whom many have a discogenic source, the use of discography should be considered to maximize the surgical success rate.28,35,40–45 This topic is discussed later in the section on surgical outcomes for axial neck pain.

To provide a surgical solution, objectification is the crucial factor. Because of the numerous asymptomatic individuals with positive MRI studies, procedures based on MRI alone for level selection in patients with dominant axial pain would have to have a very strong clinical correlation, such as a component of radiculopathy that fits with a specific herniated nucleus pulposus. Schellhas and colleagues35 published an article on the prospective correlation of discography and MRI in asymptomatic subjects and subjects with neck pain. These investigators concluded that MRI did not reliably identify the source of discogenic pain because annular tears often escape detection. It was not surprising that degenerative anatomic findings existed in the asymptomatic group. In only 3 of the 40 discs studied in asymptomatic individuals was there an elicited pain response, however, suggesting a favorable specificity and positive predictive value.35

The use of cervical discography is common practice at the author’s center. It is ordered at multiple levels and is similar in nature to the practices of other authors.37,40,41 The key is to have a significant (>6 of 10) concordant reproduction of the patient’s presenting axial pain at the affected disc level with little or no pain at the adjacent control level. This concordant pain is the pain that the patient desires to be alleviated with surgical intervention.

Regarding the complications of discography, the published rates of discitis are very low (≤1%).35,40,46 This low rate encompasses the technical skill of the discographer, size of the needle, and use of antibiotics.

Comments on facet joint blocks or medial facet rami blocks are limited here. The author knows of no peer review literature that bases a decision to proceed with fusion surgery dictated by this testing. Most of the literature on these blocks has been with the diagnostic value of an anatomic source, and specifically in patients with whiplash-associated disorder.47–49 Although some publications have suggested relief of pain associated with whiplash and in patients with chronic axial neck pain (with or without traumatic etiology), the author’s experience has not favorably reproduced those outcomes.

Surgical Outcomes for Axial Neck Pain

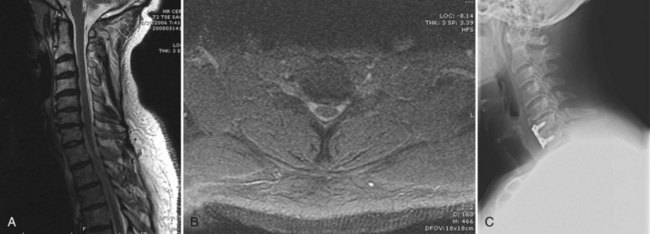

The pragmatic question to the surgeon is this: “Does your selection process, based on whatever criterion you choose, yield a reproducible, discernible impact on the patient’s chief complaint, which at 2- to 5-year follow-up would lead that patient to repeat the procedure and self-rate that surgical intervention as successful?” The currently discussed diagnostic workup approach has led the author to reply to that question with an affirmative response (Fig. 39–2).

Although prospective randomized trials are considered of higher value, much can also be gleaned from the cohort observational–based surgical literature.28,37,41–45,50–55 In a clever tongue-in-cheek meta-analysis of the protective effect to the gravitational force affected by a parachute, Smith and Pell56 found no published prospective randomized trials of such! No one doubts the value of a parachute, or for that matter of a hip arthroplasty, yet one does discount surgical treatment of axial pain.

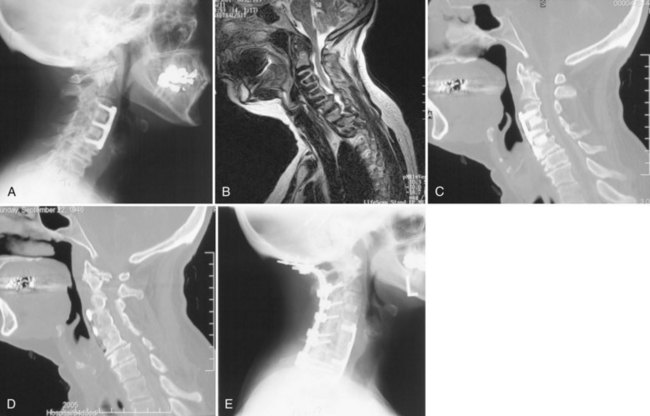

In a series of 112 consecutive patients, the author and his colleagues were able to obtain 87 responses to an extensive follow-up questionnaire at an average of 4.4 years. In this group, 20 patients had multilevel procedures, whereas 67 had single-level or two-level ACDF. The author and colleagues reported by fusion level and etiology (traumatic, workers’ compensation, or degenerative) but found no statistical difference among the groups. Pain improvement was noted in 93% (81 of 87), with the average VAS decreasing from 8.4 before surgery to 3.8 at long-term follow-up. On a 6-point Likert scale of excellent, very good, good, fair, poor, or terrible, 82% (71 of 87) self-rated their outcome to be good, very good, or excellent. Two modified cervical functional assessments were used, with the patient reporting an average 50% improvement on both. A negative correlation with the presence or absence of compensation or litigation or with tobacco use was not documented. The author and colleagues estimated that the 112 patients represented 4% of the surgical practice of the attending physicians involved during the acquisition phase (Fig. 39–3).

In a 2004 publication on the value of MRI and discography in the patient selection process for ACDF, Zheng and colleagues37 reported on 55 patients with 76% good or excellent results, 18% fair results, and 6% poor results. In 1999, Palit and colleagues41 reported on 38 patients for “dominant neck pain, with no symptoms or signs of radiculopathy or myelopathy.” They used the “patient satisfaction index,” with 79% (30 of 38) indicating satisfaction with their surgical outcome and 21% (8 of 38) indicating they were not satisfied. Table 39–1 outlines series with similar diagnostic criteria after ACDF for neck pain (some in patients with arm pain) that show consistent results. The results in these series suggest that ACDF is a reasonable surgical option for neck pain in well-selected patients.

TABLE 39–1 Results of Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion for Axial Pain

| Study | No. Patients | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Zheng et al37 | 55 | 76% good or excellent, 18% fair, 6% poor |

| Garvey et al28 | 87 | 82% good or excellent, 16% fair, 2% poor |

| Ratliff and Voorhies52 | 20 | 85% satisfaction |

| Motimaya et al51 | 14 | 78.6% satisfaction |

| Palit et al41 | 38 | 79% satisfactory, 21% not satisfactory |

| Whitecloud54 | 34 | 70% good or excellent, 12% fair, 18% poor |

| Roth44 | 71 | 93% good or excellent, 1% fair, 6% poor |

| White et al53 | 28 | 62% good or excellent, 23% fair, 23% poor |

| Riley et al42 | 93 | 72% good or excellent, 18% fair, 10% poor |

| Simmons et al45 | 30 with neck pain; 51 with neck and arm pain | 78% good or excellent, 15% fair, 7% poor |

| William et al55 | 15 | 1 excellent, 3 good, 5 fair, 6 poor |

| Dohn50 | 34 | 62% good or excellent, 24% fair, 15% poor |

| Robinson, et al2 | 56 | 73% good or excellent, 22% fair, 5% poor |

Current readers must also appreciate the wealth of information available from the publications of the pioneers of ACDF surgery. In 1962, Robinson and colleagues43 reported on their continued ACDF experience. This series was of 56 patients with 80% (45 of 56) reporting neck pain, 45% (25 of 56) noting occipital pain, and 46% (26 of 56) having interscapular radiation. A traumatic etiology was noted in 68% (38 of 56), with 25 being indirect, such as a “rear-end automobile collision.” Discography was used in 84% (47 of 56) of patients. The investigators switched from preoperative use to intraoperative testing owing to the patients complaining of pain with the actual procedure. In this classic series, 73% (41 of 56) considered themselves to have good or excellent results, with 22% (12 of 56) fair and 5.5% (3 of 56) poor. Pseudarthrosis was noted in 16% (9 of 56); 4 of the 9 patients were symptomatic. The stated conclusion was “when other treatment seems impractical, anterior interbody fusion appears to be a good surgical treatment for degenerative joint and disc disease of the cervical spine.”

In 1969, Riley and colleagues42 noted quite similar results in 93 consecutive cases. In a review paper, Riley57 commented on psychosocial issues. He noted that “prolonged pain is associated with a definite emotional response which may be more disabling than the pain itself.” He noted a series of patients with chronic neck pain who also as a group were irritable and depressed, who did not generate warm patient-physician relationships, but who did respond to surgical treatment, with the disappearance of their emotional characteristics when they had successful relief of their pain.

Pseudarthrosis

Pseudarthrosis is a common diagnosis for patients presenting with a chief complaint of neck pain. Although an anatomic pseudarthrosis may exist, one must be certain that this is the source of the “neck pain.” Adjacent levels need to be assessed, and the original diagnosis that led to ACDF that resulted in pseudarthrosis should be reviewed. With that stated, the literature supports that conversion to a solid arthrodesis yields 70% to 80% good to excellent clinical outcomes.58–60 The reports vary regarding repeat anterior procedures, posterior procedures, and combinations of both. The key is to have a specific objective diagnosis and then remedy that pathologic process.

Some patients present with new or continued complaints of neck pain after having had fusion surgery. Although the presence of an anatomic pseudarthrosis can be documented by radiographic or CT scan evaluation, one must assess the patient carefully to determine that this objective finding of pseudarthrosis is the specific etiology for the pain. The original diagnosis that led to ACDF, the timing of onset of neck pain (usually early but not immediate), and the health of the adjacent segment all must be considered. With that noted, the literature supports 70% to 80% good to excellent outcomes with conversion to a solid arthrodesis.58–62 Reports vary regarding anterior, posterior, or combined approaches, but Carreon and colleagues62 noted a greater effectiveness of the posterior approach.

Disc Arthroplasty

Cervical disc arthroplasty has been a very hot topic in recent years. Much has been published. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) investigational device exemption studies and others have allowed clinicians to garner much information about the patient’s perceived outcomes as related to neck and arm pain in both arthroplasty groups and their control groups.63–67 When one looks at the detailed data of these studies, an interesting point is that with inclusion criteria specifically having the patient treated for radiculopathy or myelopathy, the studies generally all report VAS scores for neck pain and arm pain. Generally, the VAS preoperatively is roughly equal for the arm and neck pain components—that is, each is in an approximate 7 to 8 of 10 points range, and on average decreases to a 2 to 3 of 10 points range postoperatively. What this means is that to the patient, neck pain is significant, and for outcomes, predictably it is relieved, just as is the arm pain.

When one asks what makes a patient satisfied with the outcome of surgery, Skolasky and colleagues68 noted regarding fusions that “clinical improvement, especially in neck pain, after surgery is associated with improved patient satisfaction.” In the arthroplasty control group of ACDF, Anderson and colleagues69 studied 26 potential variables, as related to overall clinical success, and found that workers’ compensation status and weak narcotic use were negative predictors, whereas higher preoperative NDI scores and normal sensory examinations were positive predictors.

Summary

Key Points

1 Garvey T, Transfeldt E, Malcolm J, et al. Outcome of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion as perceived by patients treated for dominant axial-mechanical cervical spine pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:1887-1895.

2 Robinson R, Walker E, Ferlic D, et al. The results of anterior interbody fusion of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44:1569-1587.

This is a pioneer’s work on ACDF for cervical discogenic syndrome, still valuable 50 years later.

3 Gore D, Sepic S, Gardner G, et al. Neck pain: A long-term follow-up of 205 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1987;12:1-5.

This is a classic natural history study on patients presenting with neck pain caused by spondylosis.

4 Schellhas K, Smith M, Gundry C, et al. Cervical discogenic pain: Prospective correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in asymptomatic subjects and pain sufferers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:300-311.

5 Heller JG, Sasso RC, Papadopoulos SM, et al. Comparison of BRYAN cervical disc arthroplasty with anterior cervical decompression and fusion: Clinical and radiographic results of a randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:101-107.

1 Auvinen JP, Paananen MVJ, Tammelin TH, et al. Musculoskeletal pain combinations in adolescents. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1192-1197.

2 Bovim G, Schrader H, Sand T. Neck pain in the general population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:1307-1309.

3 Cote P, Cassidy J, Carroll L. The factors associated with neck pain and its related disability in the Saskatchewan population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1109-1117.

4 Makela M, Heliovaara M, Sievers K, et al. Prevalence, determinants and consequences of chronic neck pain in Finland. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:1356-1367.

5 Manchikanti L, Singh V, Datta S, et al. Comprehensive review of epidemiology, scope and impact of spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2009;12:35-70.

6 Badcock LJ, Lewis M, Hay EM, et al. Consultation and the outcome of shoulder-neck pain: A cohort study in the population. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2694-2699.

7 Gore D, Sepic S, Gardner G, et al. Neck pain: A long term follow-up of 205 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1987;12:1-5.

8 Rothman R. The Spine, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1982.

9 DePalma A, Subin D. Study of the cervical syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1965;38:135-141.

10 DePalma A, Rothman R, Lewinnek G, et al. Anterior interbody fusion for severe cervical degeneration. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1972;134:755-758.

11 Rothman R, Rashbaum R. Pathogenesis of signs and symptoms of cervical disc degeneration. In: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 1978. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1978:203-215.

12 Walker MJ, Boyles RE, Young BA, et al. The effectiveness of manual physical therapy and exercise for mechanical neck pain: A randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:2371-2378.

13 Lees F, Turner J. Natural history and prognosis of cervical spondylosis. BMJ. 1963;2:1607-1610.

14 Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20(8S):3s-73s.

15 Freeman M, Croft A, Rossignol A, et al. A review and methodologic critique of the literature refuting whiplash syndrome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:86-98.

16 Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carette S, et al. Protocol of a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of physician education and activation versus two rehabilitation programs for the treatment of whiplash-associated disorders: The University Health Network Whiplash Intervention Trial. Trials. 2008;9:75.

17 MacNab I. Acceleration injuries of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1964;46:1797-1799.

18 MacNab I. The “whiplash syndrome.”. Orthop Clin North Am. 1971;2:389-403.

19 Hohl M. Soft-tissue injuries of the neck in automobile accidents: Factors influencing prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:1675-1682.

20 Bannister G, Gargan M. Prognosis of whiplash injuries: A review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;7:557-569.

21 Gargan M, Bannister G. Long-term prognosis of soft-tissue injuries of the neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:901-903.

22 Watkinson A, Gargan M. Prognostic factors in soft tissue injuries of the cervical spine. Injury. 1991;23:307-309.

23 Hildingsson C, Toolanen G. Outcome after soft-tissue injury of the cervical spine: A prospective study of 93 car accident victims. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61:357-359.

24 Jonsson H, Cesarini K, Sahlstedt B, et al. Findings and outcome in whiplash-type neck distortions. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:2733-2743.

25 Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Pierre Cote DC, et al. Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1179-1186.

26 Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Cassidy JD, et al. Early aggressive care and delayed recovery from whiplash: Isolated finding or reproducible result? Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:599-600.

27 Shapiro A, Roth R. The effect of litigation on recovery from whiplash. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;7:531-556.

28 Garvey T, Transfeldt E, Malcolm J, et al. Outcome of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion as perceived by patients treated for dominant axial-mechanical cervical spine pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:1887-1895.

29 Lawrence JT, London N, Bohlman HH, et al. Preoperative narcotic use as a predictor of clinical outcome: Results following anterior cervical arthrodesis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:2074-2078.

30 Ofiram E, Garvey TA, Schwender JD, et al. Cervical degenerative index: A new quantitative radiographic scoring system for cervical spondylosis with interobserver and intraobserver reliability testing. J Orthop Traumatol. 2009;10:21-26.

31 Ofiram E, Garvey TA, Schwender JD, et al. Cervical degenerative changes in idiopathic scoliosis patients who underwent long fusion to the sacrum as adults: Incidence, severity, and evolution. J Orthop Traumatol. 2009;10:27-30.

32 Friedenberg Z, Miller W. Degenerative disc disease of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1963;45:1171-1178.

33 Gore D, Sepic S, Gardner G. Roentgenographic findings of the cervical spine in asymptomatic people. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1986;11:521-524.

34 Boden S, McCowin P, Davis D, et al. Abnormal magnetic resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1178-1184.

35 Schellhas K, Smith M, Gundry C, et al. Cervical discogenic pain: Prospective correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in asymptomatic subjects and pain sufferers. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:300-311.

36 Teresi L, Lufkin R, Reicher M, et al. Asymptomatic degenerative disk disease and spondylosis of the cervical spine: MR imaging. Radiology. 1987;164:83-88.

37 Zheng Y, Liew S, Simmons E. Value of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in determining the level of cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:2140-2145.

38 Nordin M, Carragee EJ, Hogg-Johnson S, et al. Assessment of neck pain and its associated disorders: results of the Bone and Joint Decade 2000-2010 Task Force on Neck Pain and Its Associated Disorders. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009;32(2 Suppl):S117-S140.

39 Manchikanti L, Dunbar EE, Wargo BW, et al. Systematic review of cervical discography as a diagnostic test for chronic spinal pain. Pain Physician. 2009;12:305-321.

40 Grubb S, Kelly C. Cervical discography: Clinical implications from 12 years of experience. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1382-1389.

41 Palit M, Schofferman J, Goldthwaite N, et al. Anterior discectomy and fusion for the management of neck pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:2224-2228.

42 Riley L, Robinson R, Johnson K, et al. The results of anterior interbody fusion of the cervical spine. J Neurosurg. 1969;30:127-133.

43 Robinson R, Walker E, Ferlic D, et al. The results of anterior interbody fusion of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44:1569-1587.

44 Roth D. A new test for the definitive diagnosis of the painful-disk syndrome. JAMA. 1976;235:1713-1714.

45 Simmons E, Bhalla S, Butt W. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: A clinical and biomechanical study with eight-year follow-up. With a note on discography: Technique and interpretation of results. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1969;51:225-237.

46 Zeidman S, Thompson K. Cervical discography. In The Cervical Spine Research Society: The Cervical Spine, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Raven; 1998:205-216.

47 Barnsley L, Lord S, Wallis B, et al. The prevalence of chronic cervical zygapophysial joint pain after whiplash. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:20-26.

48 Bogduk N, April C. On the nature of neck pain, discography and cervical zygapophysial joint blocks. Pain. 1993;54:213-217.

49 Lord S, Barnsley L, Wallis B, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721-1726.

50 Dohn D. Anterior interbody fusion for treatment of cervical disk condition. JAMA. 1966;197:897-900.

51 Motimaya A, Arici M, George D, et al. Diagnostic value of cervical discography in the management of cervical discogenic pain. Conn Med. 2000;64:395-398.

52 Ratliff J, Voorhies R. Outcome study of surgical treatment for axial neck pain. South Med J. 2001;94:595-602.

53 White A, Southwick W, Panjabi M. Clinical instability in the lower cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1976;1:15-27.

54 Whitecloud T. Management of radiculopathy and myelopathy by the anterior approach. In The Cervical Spine Research Society: The Cervical Spine, 2nd ed, Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1989:644-658.

55 William J, Allen M, Harkess J. Late results of cervical discectomy and interbody fusion: Some factors influencing the results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1968;50:277-286.

56 Smith G, Pell J. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2003;327:1459-1461.

57 Riley L. Various pain syndromes which may result from osteoarthritis of the cervical spine. Maryland State Med J. 1969;18:103-105.

58 Farey I, McAfee P, Davis R, et al. Pseudarthrosis of the cervical spine after anterior arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;70:1171-1177.

59 Lowery GL, Swank ML, McDonough RF. Surgical revision for failed anterior cervical fusions: Articular pillar plating or anterior revision? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:2436-2441.

60 Zdeblick TA, Hughes SS, Riew KD, et al. Failed anterior cervical discectomy and arthrodesis: Analysis and treatment of thirty-five patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:523-532.

61 Kuhns CA, Geck MJ, Wang JC, et al. An outcomes analysis of the treatment of cervical pseudarthrosis with posterior fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:2424-2429.

62 Carreon L, Glassman SD, Campbell MJ. Treatment of anterior cervical pseudoarthrosis: Posterior fusion versus anterior revision. Spine J. 2006;6:154-156.

63 Heller JG, Sasso RC, Papdopoulos SM, et al. Comparison of BRYAN cervical disc arthroplasty with anterior cervical decompression and fusion: Clinical and radiographic results of a randomized, controlled, clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:101-107.

64 Murrey D, Janssen M, Delamarter R, et al. Results of the prospective randomized, controlled multicenter Food and Drug Administration investigational device exemption study of the ProDisc-C total disc replacement versus anterior discectomy and fusion for the treatment of 1-level symptomatic cervical disc disease. Spine J. 2008;9:275-286.

65 Mummaneni PV, Burkus JK, Haid RW, et al. Clinical and radiographic analysis of cervical disc arthroplasty compared with allograft fusion: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:198-209.

66 Sasso RC, Smucker JD, Hacker RJ, et al. Artificial disc versus fusion: A prospective randomized study with 2-year follow-up on 99 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:2933-2940.

67 Barbagallo GM, Assietti R, Corbino L, et al. Early results and review of the literature of a novel hybrid surgical technique combining cervical arthrodesis and disc arthroplasty for treating multilevel degenerative disc disease: Opposite of complementary techniques? Eur Spine J. 2009;18(Suppl 1):29-39.

68 Skolasky RL, Albert TJ, Vaccaro AR, et al. Patient satisfaction in the cervical spine research society outcomes study: Relationship to improved clinical outcome. Spine J. 2009;9:232-239.

69 Anderson PA, Subach BR, Riew KD. Predictors of outcome after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: A multivariate analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:161-166.