CHAPTER 87 Surgical Decompression for Spinal Stenosis

DEFINITION

Lumbar spinal stenosis is an abnormal narrowing of the osteoligamentous vertebral canal and/or the intervertebral foramina, which is responsible for compression of the thecal sac and/or the caudal nerve roots; narrowing of the vertebral canal may involve one or more levels and, at a single level, may affect the entire canal or a part of it.1 Thus, abnormal narrowing of the spinal canal may be considered as stenosis if two criteria are fulfilled: the narrowing involves the osteoligamentous spinal canal, and it causes compression of the neural structures.

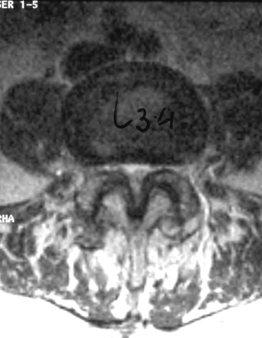

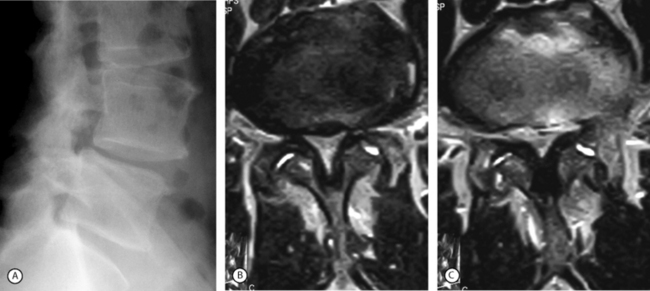

The second criterion emphasizes the concept of compression of the thecal sac and nerve roots. The term stenosis indicates a disproportion between the caliber of the container and the volume of the content. If the content is solid or semifluid, as in the vertebral canal, the dimensional disproportion results in compression of the content by the walls of the container. However, the disproportion is not strictly related to the anteroposterior dimensions of the vertebral canal, as believed by Verbiest.2 Severe compression of the neural structures may occur even if the sagittal dimensions of the canal are within normal limits. On the other hand, a midsagittal diameter of 10 mm or less does not necessarily lead to compression of the cauda equina.3 This is probably due to the fact that the neural structures develop in harmony with the dimensions of the canal. When this does not occur, the reserve space available for the thecal sac and/or the caudal nerve roots is variably reduced and, therefore, acquired constrictive conditions of even minor degree are sufficient to cause stenosis. If the narrowing is not severe enough to cause compression of the neural structures, the spinal canal is to be considered narrow but not stenotic. Therefore, a diagnosis of stenosis cannot be made solely on the basis of measurements of the size of the vertebral canal or the area of the thecal sac in the axial sections. The radiologic diagnosis of stenosis should be predicated upon the demonstration of compression of the neural structures, whether clinically symptomatic or asymptomatic, by an abnormally narrow osteoligamentous spinal canal (Fig. 87.1).

CLASSIFICATION

Site of constriction

Lumbar spinal stenosis can be distinguished, based on the site of constriction, as stenosis of the spinal canal or central stenosis, isolated stenosis of the nerve root canal or lateral stenosis, and stenosis of the intervertebral foramen (Table 87.1).

| CENTRAL STENOSIS | |

| Primary | |

| Congenital | |

| Developmental | |

| Achondroplastic | |

| Constitutional | |

| Secondary | |

| Degenerative | |

| Simple | |

| With degenerative spondylolisthesis or scoliosis | |

| Late sequelae of fractures or infections | |

| Paget’s disease | |

| Combined | |

| Association of primary and secondary forms at the same vertebral level | |

| ISOLATED LATERAL STENOSIS | |

| Primary | |

| Secondary | |

| Combined | |

| STENOSIS OF THE INTERVERTEBRAL FORAMEN | |

| Primary | |

| Secondary | |

| Combined | |

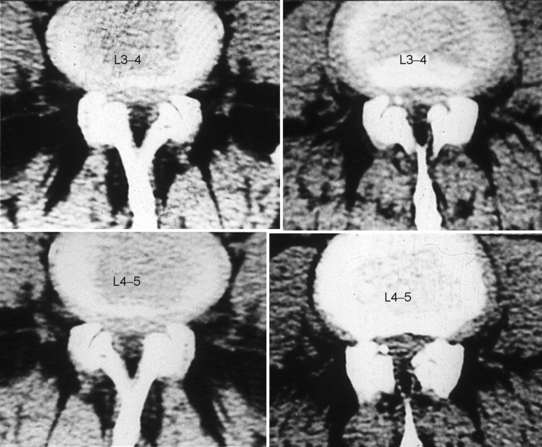

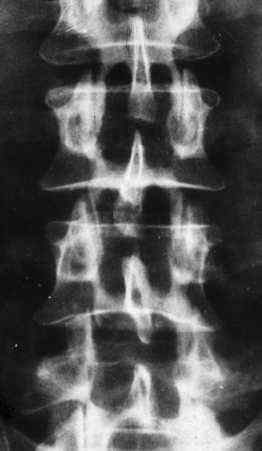

In stenosis of the spinal canal, the entire area of the canal, as viewed on the axial plane, is usually constricted (Fig. 87.2). In other words, both the central portion of the canal and the lateral parts, occupied by the emerging nerve roots, are constricted. Therefore, the expression stenosis of the spinal canal is more correct than that of central stenosis, which would indicate constriction only of the central area. However, the authors will use the latter term because it has become the one commonly adopted.

The nerve root canal or radicular canal corresponds to the lateral portion of the spinal canal (Fig. 87.3). This canal, which is more of an anatomical concept than a true canal, is the semitubular structure in which the nerve root, exiting from the thecal sac, travels before entering the intervertebral foramen. As for the central form, in the last decade, the term lateral stenosis has become the most widely used for this type of stenosis.

Type of stenosis

Three forms of stenosis can be identified: primary, secondary and combined (see Table 87.1).

Primary forms

Central stenosis

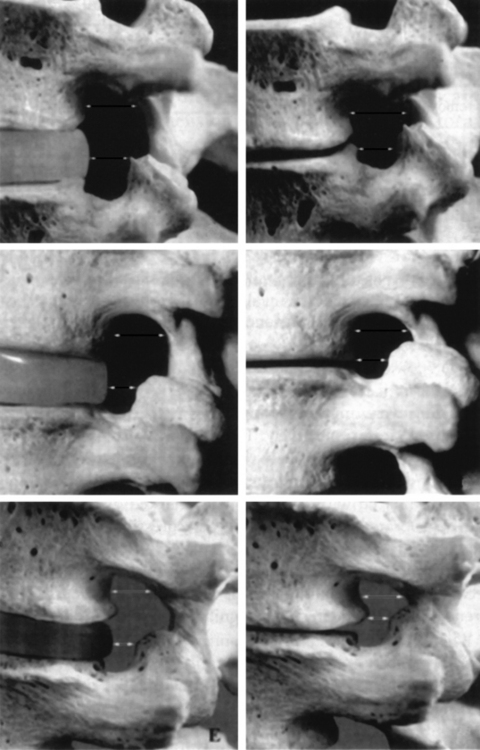

Developmental stenosis includes achondroplastic and constitutional forms. In the former, the midsagittal and/or interpedicular diameters of the spinal canal are abnormally short and the nerve root canals are severe narrowed due to abnormal shortness of the pedicles. In constitutional stenosis the cause of the defective vertebral development is unknown. In the authors’ experience, two types of constitutional abnormality may be identified: (1) a short midsagittal diameter of the spinal canal, and (2) an exceedingly sagittal orientation and/or shortness of the pedicles (Fig. 87.4). In the latter type, the spinal canal is abnormally narrow, mainly or only, in the inter-articular diameter.

Secondary forms

Central stenosis

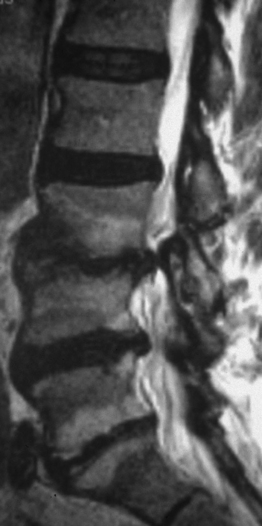

If the sagittal dimensions of the spinal canal are normal, or at the lower limits, and compression of the caudal nerve roots is the result of one or more acquired conditions, such as spondylotic changes of the facet joints, abnormal thickening of the ligamenta flava, and bulging of the intervertebral discs, then this form is defined as simple degenerative stenosis (Fig. 87.6).

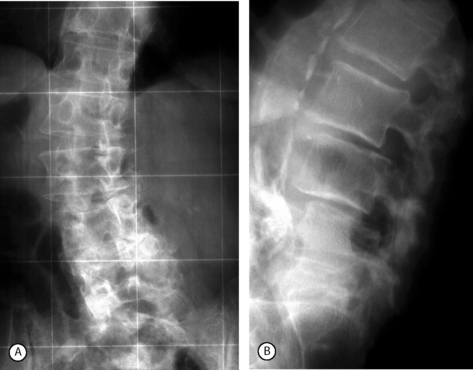

Very often, however, degenerative spondylolisthesis of the cranial vertebra of the motion segment is also present at one or, occasionally, two or more levels (Fig. 87.7). Degenerative spondylolisthesis is consistently responsible for narrowing of the spinal canal, but may not cause lateral or central stenosis. This is because the presence, type, and severity of stenosis is related to several factors, such as the constitutional dimensions of the spinal canal, the orientation (more or less sagittal), and the severity of degenerative changes of the facet joints, and the amount of vertebral slipping, which may in some cases play a minor role. For example, a grade I spondylolisthesis in a patient with a constitutionally large spinal canal produces no significant narrowing of the canal, would be categorized as no stenosis. In contrast, the same or even lesser grade of spondylolisthesis in a patient with a primarily narrow canal can be associated with clinically significant stenosis. The type of stenosis, that is whether stenosis is central or lateral, depends on the orientation of the articular processes and the length of the pedicles. Usually, stenosis initially presents as lateral and then central in later stages. Instability, that is hypermobility on flexion–extension radiographs, is one of the main characteristics of degenerative spondylolisthesis. However, in many cases there is no appreciable hypermobility of the slipped vertebra. The authors consider the latter condition as a potential instability, which can become unstable as a result of surgery. Such a scenario may arise following removal of a large part of one or both facet joints, unilateral or bilateral discectomy, or when destabilizing factors unable to stabilize a normal vertebra intervene, such as disc degeneration or severe degenerative changes of the facet joints. In degenerative spondylolisthesis, the intervertebral disc often bulges into the intervertebral foramen to cause stenosis. However, true stenosis of the foramen is rarely present as the foramen becomes larger in the sagittal dimensions in the presence of slipping of the cranial vertebra.

Lateral stenosis

Most often, this form of stenosis is degenerative in nature. Usually, degenerative stenosis involves only the lateral portions of the spinal canal in the initial stages and become central in more advanced stages when spondylotic changes becomes more severe. This is particularly true for degenerative spondylolisthesis.

Lateral stenosis can occur due to a cyst of the facet joint when it compress the emerging root in the nerve root canal (Fig. 87.8).

INDICATIONS FOR SURGERY

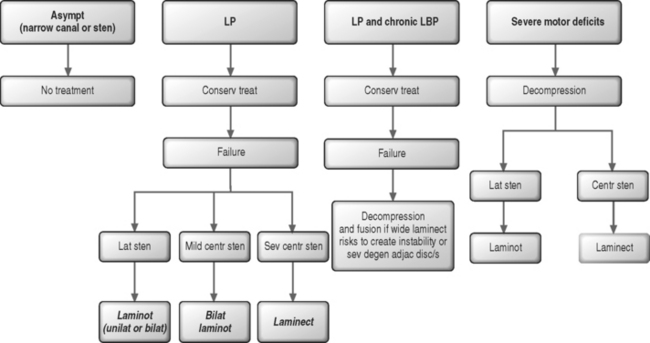

In patients with leg symptoms, surgery is indicated when comprehensive conservative management as described in other chapters of this book have been carried out for 4–6 months without resulting in significant improvement (Fig. 87.9). The exception to this recommendation is for patients with a severe motor and/or sensory deficit consistent with cauda equina syndrome, who require emergent neural decompression.

Usually, there is no need for spinal fusion. Arthrodesis may be indicated when there is a concern that wide surgical decompression could result in postoperative instability. Additionally, fusion may be required for the patient that is experiencing simultaneous radicular pain from spinal stenosis and axial back pain due to internal disc disruption syndrome (see Fig. 87.9).

Advanced age

Surgical decompression may offer significant relief of symptoms also to patients older than 70 years.5–8 In the authors’ experience, there is no significant difference in the results of surgery between the patients in early senile age and those aged 80–90 years old, provided the stenosis is severe and the patient’s general health is satisfactory.

Comorbidity

In one study,7 a high rate of comorbid illnesses was found to be inversely related to the rate of satisfactory results after surgery. Another study9 compared the long-term results of surgery in 24 diabetic and 22 nondiabetic patients. In the diabetic group there was a 41% rate of satisfactory results, compared with 90% in the nondiabetic group. Different results, however, were observed in a similar study,10 in which the outcome was satisfactory in 72% of the diabetic and 80% of the nondiabetic patients. Neither the duration of the diabetes before surgery nor its type correlated with the outcome. A mistaken preoperative diagnosis was the main cause of failure in diabetic patients. In many of the failures, diabetic neuropathy or angiopathy had elicited symptoms that had been confused with pseudoclaudication.

Previous surgery

Surgery for spinal stenosis tends to give less satisfactory results in patients who had previously undergone decompressive procedures in the lumbar spine.7,11–14 This is particularly true when stenosis is at the same level or levels at which the previous surgery for disc herniation or stenosis had been performed.15

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Definition of terms

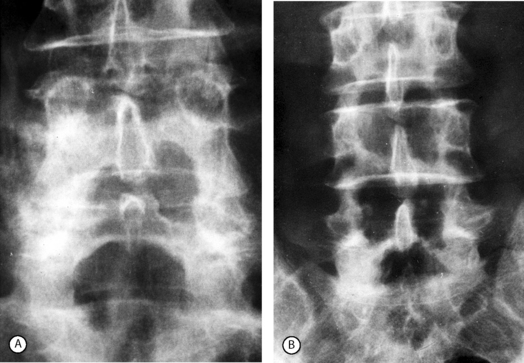

Decompression of the lumbar spinal canal can be carried out by total laminectomy, also defined as bilateral or complete laminectomy (Fig. 87.10). More focal decompression can be accomplished with a laminotomy, also called keyhole laminotomy, hemilaminectomy, or partial hemilaminectomy. Laminotomy consists in the removal of the caudal portion of the proximal lamina, the cranial portion of the distal lamina and a varying portion of the articular processes, together with a part of, or the entire, ligamentum flavum on the side of surgery. Laminotomy can be performed at a single level on one side or both sides (Fig. 87.11). Less frequently it is performed at multiple levels (Fig. 87.12).

Fig. 87.11 Unilateral laminotomy (arrow) (A) and bilateral laminotomy (arrows) (B) at two contiguous levels.

The term foraminotomy indicates removal of a part of the posterior wall of the intervertebral foramen, while the term foraminectomy refers to complete excision of the wall of the foramen.

Types of stenosis

Stenosis without concurrent spondylolisthesis or scoliosis

Central stenosis

Extent of decompression

The long-term results of surgery may deteriorate with time because of regrowth of the resected portion of the posterior vertebral arch.16 This is more likely to occur when a narrow decompression is performed. The authors believe that decompression should be as wide as possible in the lateral portion of the spinal canal, while at the same time preserving vertebral stability. The optimal facetectomy is that in which the medial two-thirds of the superior and inferior articular processes are removed. An important concept is that in lumbar stenosis radicular symptoms originate from compression of the nerve root after it has emerged from the thecal sac, that is in the radicular canal, rather than within the thecal sac.

Methods of decompression

In the past few years, the technique of multiple laminotomy, or its variants, has become widely used in the treatment of central spinal stenosis because it preserves vertebral stability better than central laminectomy does.17,18 However, a major role is still played by total laminectomy, which often allows for a more effective decompression of the neural structures. Multiple laminotomy is the treatment of choice for constitutional stenosis because the patients are usually middle-aged, the stenosis is rarely severe, and disc excision is often necessary in addition to decompression.18 Similarly, a multilevel laminotomy is preferred for degenerative or combined stenosis when narrowing of the spinal canal is mild or moderate, particularly if a disc excision has been planned. Total laminectomy is typically more effective for severe stenosis, providing that the involved segments are stable preoperatively. When this is not the case, the choice is between multiple laminotomy and total laminectomy combined with fusion of the decompressed segments.

Isolated lateral stenosis

In this condition, only one vertebral level is usually involved.

Discectomy should generally be planned for patients in whom preoperative investigations show evidence of a bulging intervertebral disc at the stenotic level. Preoperatively, however, it is often difficult to determine the precise role played by the intervertebral disc in the etiology of nerve root compression. In these cases, the decision about whether to carry out disc excision must be made on the basis of the operative findings after exploring the canal.

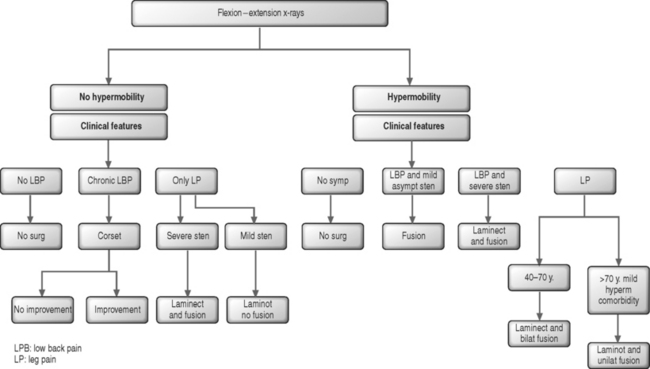

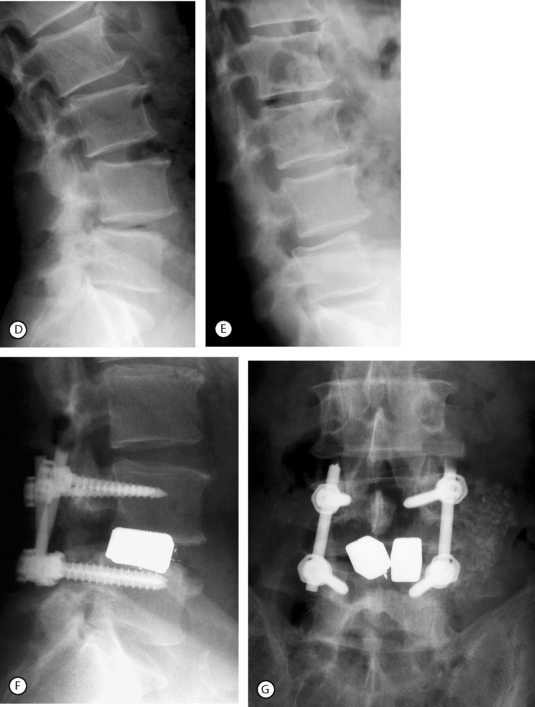

Degenerative spondylolisthesis

In the authors’ experience, bilateral laminotomy, or even total laminectomy, may be carried out with no concomitant fusion in patients with mild olisthesis, no vertebral hypermobility on flexion–extension radiographs, mild central stenosis or any degree of isolated lateral stenosis, and mild or no back pain (Fig. 87.13). Similarly, in elderly patients with moderate olisthesis and marked resorption of the disc below, no vertebral hypermobility, and stenosis requiring total laminectomy, there may be no indication for fusion. This tenet is particularly applicable in the absence of significant chronic low back pain or in the presence of comorbid diseases which require a rapid operation. The indications for monolateral laminotomy with no fusion are: moderate central stenosis in elderly patients with unilateral symptoms; lateral stenosis only on one side; and unilateral additional pathology, such as a ipsilateral synovial cyst provided there is no contralateral leg pain and no chronic back pain.

In the presence of moderate or severe olisthesis, vertebral hypermobility even of mild degree, and/or severe central stenosis and chronic back pain patients should undergo decompression and fusion (see Fig. 87.13). In these instances, the association of an arthrodesis allows the surgeon to decompress the neural structures as widely as necessary.

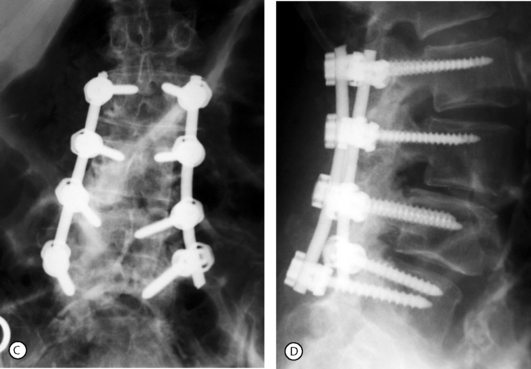

Posterolateral (intertransverse process) fusion with no pedicle screw instrumentation is the gold standard because the fusion is less rigid and a small residual mobility of the fused vertebrae remains, which decreases the mechanical stresses on the adjacent motion segments. However, the drawbacks are the necessity of a prolonged, rigid immobilization following surgery. Posterolateral instrumented fusion, using pedicle screw fixation, has become the most common procedure (Fig. 87.14). The procedure can be done at multiple levels when olisthesis is present at more than one level (Fig. 87.15). In both cases it requires no, or a short period of, postoperative immobilization.

Internal fixation may be bilateral or unilateral. The latter, which decreases the potential morbidity of the bilateral fixation (increased stress on the adjacent unfused segments) was found to give similar results in terms of fusion rate as the bilateral instrumentation.20 The authors have performed bilateral bone grafting and unilateral instrumentation or unilateral bone grafting and instrumentation in 36 cases with a 97% rate of solid fusion. The advantages of the unilateral instrumentation are a shorter operative time, decreased risk of neurological complications, and reduced costs. The main indications are: back pain with mild segmental instability in the elderly, or concern of producing gross instability after a total laminectomy.

Some surgeons prefer to perform a posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) in lieu of a posterolateral fusion. This procedure, when used in tandem with pedicle screw instrumentation, provides excellent results and a high rate of solid fusion. The devices inserted in the disc space are normally represented by cages filled with bone chips. An alternative is to use blocks of porous tantalum (hedrocel), the stiffness of which is very similar to that of subchondral bone. Animal model studies have shown bone ingrowth within the pores of the implant and maturation of the osteoid in some 3 months. The authors have used blocks of hedrocel for 3 years with excellent results of this interbody fusion (Fig. 87.16). In 16 cases followed for at least 2 years, there has been no observed migration of the implant or loosening of the pedicle screws. The authors have invariably observed a tight union between the implant and the adjacent vertebral endplates as assessed by MRI and/or plain X-rays.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Total laminectomy

Disinsertion of paraspinal muscles

Elevation of the paraspinal muscles from their insertion starts at the most cranial of the exposed vertebrae. A broad periosteal elevator is introduced deep to the muscle mass and allowed to slip along the outer surface of the spinous process and lamina to detach the paraspinal muscles from the bone surface until the lateral border of the facet joints is reached. Dry sponges are then packed, using the periosteal elevator, beneath the muscle mass. This maneuver is aimed at both disengaging the paraspinal muscles from the lateral portion of the laminae and apophyseal joints, and arresting bleeding from the posterior branches of the lumbar arteries and veins. Sponges packed at the level of two contiguous vertebrae are subsequently removed and, while retracting the muscle mass, the residual musculotendinous attachments to the base of the spinous processes and interspinous ligaments are sectioned. When decompression is needed at more than one motion segment, dry sponges are again packed into the depth of the wound and the vertebrae and intervertebral spaces below are exposed.

Opening of the spinal canal

An alternative technique, which the authors prefer, is to perform laminectomy using chisels. After removal of the spinous processes and detachment of the ligamentum flavum from the lamina of the proximal vertebra, a chisel is used to remove, first, the caudal half of the lamina of the proximal vertebra and then the medial half of the inferior articular process of the same vertebra. The proximal portion of the lamina of the distal vertebra can be removed partly by the chisel (posterior portion) and partly using a rongeur (deep portion, closer to the thecal sac and nerve root). After removal of the ligamentum flavum as extensively as possible and exposure of the thecal sac, the residual lateral portions of the articular processes are removed using both chisels, 1 or 2 cm in width, and punch rongeurs. When using chisels, these should be orientated at 45° in a mediolateral and posteroanterior direction to undermine the articular processes, that is to remove only the ventral portion of the bone in order to preserve vertebral stability.12

Laminotomy

Single level

A Taylor retractor is installed against the external aspect of the articular processes and held by a metal weight of some 2 kg. The ligamentum flavum is detached using a curette from the deep surface of the proximal lamina, and the distal one-third to half of it is excised using a gouge forceps or a punch rongeur. The ligamentum flavum is disinserted from the proximal border of the distal lamina. This allows a rongeur to be introduced under the lamina, about one-third of which is initially removed. Rongeurs of varying sizes are used to excise the medial half to two-thirds of the facet joint as well as the ligamentum flavum inserted on the facets. An alternative method is to use a chisel, or a high-speed microdrill, to remove a portion of the proximal lamina and the medial portion of the inferior articular process of the proximal vertebra. The remaining ligamentum flavum is excised by cutting it with a scalpel or a rongeur.

RESULTS OF SURGERY

Overall results

Central stenosis

Of the 92 patients followed by Verbiest,2 for 1–20 years, 18% had no significant symptoms. In the remaining cases, back pain was the most frequent symptom. The highest rate of excellent results was obtained in the patients with the most severe stenoses. Lassale et al.21 evaluated 128 patients 2–14 years after surgery using a grading scale of 0 to 20. Satisfactory results were observed in 83% of patients. On the grading scale, four profiles were identified: a stable result (60%), regular improvement (14%), improvement with episodic aggravation of symptoms (19%), and subsequent worsening (8%). In a prospective study22 of 140 patients, an average leg pain improvement of 82% and back pain improvement of 71% was found a mean of 3 years after surgery. Similar results were reported in other series of the 1970s and 1980s.12,23–25 In a series of 77 patients,26 average age of 65 years of age, who were followed for 2–5 years, 83% had a satisfactory result. Younger patients had a greater reduction in severity scores. However, satisfaction was similar in both older and younger patients.

Postacchini et al.27 reviewed 64 patients at a mean of 8 years (range, 4–21 years) after surgery. The long-term results were excellent or good in 67% of patients and fair or poor in 33%. However, of the patients with unsatisfactory results, 15% already showed an unsatisfactory outcome in the first year after surgery. Thus, only 13% of patients had a deterioration of the result with time. The majority of the patients who underwent radiographs during the follow-up period and/or at the most recent follow-up showed regrowth of the resected portion of the posterior vertebral arch.16 Regrowth was marked in 13% of cases (Fig. 87.17). In two cases, the regrowth produced recurrence of stenosis, which required repeat surgery.

In a study in which 37 patients were followed for a minimum of 10 years, no impairment in activity of daily living was found in 62% of the cases.28 The rate of improvement was evaluated as excellent or good in 57%, fair in 22% and poor in 22%.

Lateral stenosis

Proportions of satisfactory results ranging 79–93% were obtained by several authors using laminotomy or total laminectomy.17,29–31 Venner and Crock32 reviewed 45 patients with stenosis of the S1 radicular canal and isolated resorption of the fifth lumbar disc. An excellent result was obtained by 62% and a good result by 25% of patients. Results were satisfactory in 83% of 43 cases followed for 3 years on average by Postacchini;15 good to excellent outcomes were observed in 90% of patients with preoperative motor deficit or reflex changes and in 71% of those without neurological deficits.

Degenerative spondylolisthesis

Several studies, particularly in past decades, have reported satisfactory results with decompression alone.33–36 In the past two decades, fusion (with or without pedicle screw instrumentation) has been associated more and more often to decompression,37–42 with very high percentages of satisfactory results. In the authors’ experience, the association of arthrodesis is mandatory in the presence of gross instability, particularly when total laminectomy is carried out. In other situations (such as mild olisthesis and potential instability or unilateral decompression, in patients with no back pain) only decompression can be performed with excellent outcomes.

1 Postacchini F. Lumbar spinal stenosis and pseudostenosis. Definition and classification of pathology. Ital J Orthop Traumatol. 1983;9:339-351.

2 Verbiest H. Results of surgical treatment of idiopathic developmental stenosis of the lumbar vertebral canal. A review of twenty-seven years experience. J Bone Joint Surg. 1977;59B:181-188.

3 Postacchini F, Ripani M, Carpano S. Morphometry of the lumbar vertebrae. An anatomic study in two caucasoid ethnic groups. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1983;172:296-303.

4 Cinotti G, De Santis P, Nofroni I, et al. Stenosis of the intervertebral foramen. Anatomic study on predisposing factors. Spine. 2002;27:223-229.

5 Herron LD, Mangelsdorf C. Lumbar spinal stenosis: results of surgical treatment. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4:26-33.

6 Johnsson KE, Udén A, Rosén I. The effect of decompression on the natural course of spinal stenosis. A comparison of surgically treated and untreated patients. Spine. 1991;16:615-619.

7 Katz IN, Lipson SJ, Larson MG, et al. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73A:809-811.

8 Sanderson PL, Wood PLR. Surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis in old people. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75B:393-397.

9 Simpson JM, Silveri CP, Balderstone RA, et al. The results of operations on the lumbar spine in patients who have diabetes mellitus. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75A:1823-1829.

10 Cinotti G, Postacchini F, Weinstein JN. Lumbar spinal stenosis and diabetes. Outcome of surgical decompression. J Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76B:215-219.

11 Boccanera L, Pelliccioni S, Laus M. Stenosis of the lumbar vertebral canal (a study of 25 cases operated on). Ital J Orthop Traumat. 1984;10:227-236.

12 Getty CJM. Lumbar spinal stenosis. The clinical spectrum and the results of operation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62B:481-485.

13 Herron LD, Mangelsdorf C. Lumbar spinal stenosis: results of surgical treatment. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4:26-33.

14 Nasca RJ. Rationale for spinal fusion in lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1989;14:451-454.

15 Postacchini F. Lumbar spinal stenosis. Vienna: Springer Verlag, 1989.

16 Postacchini F, Cinotti G. Bone regrowth after surgical decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74B:862-869.

17 Aryanpur J, Ducker T. Multilevel lumbar laminotomies: an alternative to laminectomy in the treatment of lumbar stenosis. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:429-433.

18 Postacchini F, Cinotti G, Perugia D, et al. The surgical treatment of central lumbar stenosis. Multiple laminotomy compared with total laminectomy. J Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75B:386-392.

19 Grob D, Humke T, Dvorak J. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Decompression with and without arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77A:1036-1041.

20 Kabins MB, Weinstein JN, Spratt KF, et al. Isolated L4–L5 fusion using the variable screw placement system: unilateral versus bilateral. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5:39-49.

21 Lassale B, Deburge A, Benoist M. Resultatts à long terme du traitment chirurgical des stenoses lombaires operées. Rev Rheum. 1985;52:27-33.

22 Herron LD, Mangelsdorf C. Lumbar spinal stenosis: results of surgical treatment. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4:26-33.

23 Paine KWE. Results of decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin Orthop. 1976;115:96-100.

24 Hasue M, Kida H, Inoue K, et al. Lumbar spinal stenosis. A clinical study of symptoms and therapeutic results. Int Orthop (SICOT). 1977;1:133-137.

25 Tsuji H, Tamaki T, Itoh T, et al. Redundant nerve roots in patients with degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1985;10:72-82.

26 Hansray KKH, Cammisa FP, O’Leary PF, et al. Decompressive surgery for typical lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin Ortop. 2001;384:11-17.

27 Postacchini F, Cinotti G, Gumina S, et al. Long-term results of surgery in lumbar stenosis: 8-year review of 64 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;Suppl 251:78-80.

28 Iguchi T, Kurihara A, Nakayama J, et al. Minimum 10-year outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 2000;25:1754-1759.

29 Choudury AR, Taylor JC. Occult lumbar spinal stenosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1977;40:506-510.

30 Tile M, McNeil SR, Zarins RK, et al. Spinal stenosis. Results of treatment. Clin Orthop. 1976;115:104-108.

31 Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Wedge JH, Yong-Hing K, et al. Lumbar spinal nerve lateral entrapment. Clin Orthop. 1982;169:171-178.

32 Venner RM, Crock HV. Clinical studies of isolated disc resorption in the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63B:491-494.

33 Cauchoix J, Benoist M, Chasseing V. Degenerative spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop. 1976;115:122-129.

34 Rosenberg NJ. Degenerative spondylolisthesis. Surgical treatment. Clin Orthop. 1976;117:112-120.

35 Herron LD, Trippi AC. Degenerative spondylolisthesis. The results of treatment by decompressive laminectomy without fusion. Spine. 1989;14:534-538.

36 Epstein NE, Epstein JA, Carras R, et al. Degenerative spondylolisthesis with an intact neural arch: a review of 60 cases with an analysis of clinical findings and the development of surgical management. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:555-561.

37 Hanley EN. Decompression and distraction–derotation arthrodesis for degenerative spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1986;11:269-276.

38 Knox BD, Harvell JC, Nelson PB, et al. Decompression and Luque rectangle fusion for degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord. 1989;2:223-228.

39 Herkowitz HN, Kurz LT. Degenerative spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis. A prospective study comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73A:802-808.

40 Caputy AJ, Lussenhop AJ. Long-term evaluation of decompressive surgery for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:669-676.

41 Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Chang LC, et al. Seven-to10-year outcome of decompressive surgery for degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1996;21:92-98.

42 Garfin SR, Herkowitz HN, Mirkovic S. Spinal stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1999;81A:572-586.