Chapter 51 Surgical Approaches to the Orbit

The surgical treatment of orbital processes presents a border area between different surgical specialties, including otorhinolaryngology, oral/maxillofacial surgery, ophthalmology, and neurosurgery. Neurosurgeons encounter more neural tumors such as meningiomas and optic pathway gliomas in contrast to ear, nose, and throat (ENT) or head and neck surgeons, who more often deal with secondary lesions such as mucoceles and paranasal sinus neoplasms. Patients treated by ophthalmologists have a greater incidence of thyroid-related orbitopathy and inflammatory pseudotumor. 1

History

The history of orbital approaches begins in the 19th century. Krönlein performed the first extracranial orbitotomy in 1889 and Berke in 1954. 2,3 Kennerdell and Maroon picked up this approach in 1988.4 Niho5 chose a transethmoidal approach in 1970, Colohan6 a frontal trans-sinusoidal path in 1985, and Hassler7 a transconjunctival approach in 1994.

Regarding the transcranial approaches, the subfrontal approaches published by Dandy8 in 1941 and Housepian9 in 1978 are well recognized. Naffziger10 chose a frontolateral pterional approach in 1948. In 1964 and 1975, Yasargil11 reported about experiences with the same approach. Kennerdell and Maroon4 also operated via this frontolateral approach. Seeger and Hassler used a pterional extradural approach in 1983 and 1985.12 Dolenc13,14 opened the orbit by unroofing it while operating on parasellar lesions and tracing them through the orbital roof directly or through the superior orbital fissure in 1983. Hassler15 described a contralateral pterional approach in 1994.

Choice of Surgical Approach

The choice of surgical approach is largely determined by the location, extension, and type of the lesion. The goals of the surgery such as biopsy, debulking, or gross-total resection have to be considered. The general guidelines recommend choosing the most direct approach, not to cross the optic nerve, and to avoid or hide skin incisions. In anterior locations, bone removal should be avoided. Today, there is a tendency towards less invasive approaches. Thus, the transcranial approaches are performed less frequently in favor of minimally invasive extracranial approaches. In most cases, the lateral orbitotomy and increasingly also the supraorbital orbitotomy are used to treat orbital pathologies. Anterior approaches without osteotomy such as superior or lower-eyelid incisions, sub-brow incision or inferior transconjunctival or subciliary incisions may be used for smaller anterior lesions.16

One of the more recently developed approaches, such as the transconjunctival, pterional (frontotemporal) contralateral, or pterional extradural approach, can be used as an alternative to a classic extracranial approach (lateral orbitotomy) or a more extensive transcranial approach.7,12,17,18 Some specialists may choose to operate through the neighboring paranasal sinuses (transethmoidal or transmaxillary approach).

Topographic Distribution

Certain types of lesions occur at certain locations (Table 51-1). Thus, the most common intraconal processes affecting the optic nerve are optic nerve glioma, optic sheath meningioma, and lymphoma. Other intraconal processes include cavernoma, neurinoma, and metastases. The intraconal space is delimited by the conus, which connects the four rectus muscles to each other. The extraconal compartment takes up only a small amount of space within the orbit, surrounding the muscular conus like a tube. The most common extraconal processes are dermoid tumor (dermoid cyst) and pleomorphic adenoma of the lacrimal gland. The subperiosteal compartment is defined as the potential space between the periosteum and the bony orbit. Mucoceles are the most common processes affecting this compartment. The bony orbit and the sphenoid wing can be the site of an osteoma, a malignant tumor, or fibrous dysplasia, but the most common process affecting these structures is a sphenoid wing meningioma. Meningiomas are often found at the orbital apex, the superior orbital fissure, and the cavernous sinus. The intracranial periorbital dura mater heading toward the optic nerve may be infiltrated by an optic sheath meningioma or by other types of meningioma of variable size and extent. Pleomorphic adenomas and carcinomas arise within the lacrimal gland and duct system. Lymphomas and infections can affect the preseptal segment or the lids.

| Intraconal (optic nerve) | Optic nerve glioma, optic nerve sheath meningioma |

| Intraconal | Cavernoma, schwannoma, metastases, lymphoma, lymphangioma |

| Extraconal | Dermoid cyst, pleomorphic adenoma of the lacrimal gland, pseudotumor |

| Subperiosteal | Mucocele |

| Sphenoid wing, bony orbit | Meningioma, osteoma, malignant tumor, fibrous dysplasia |

| Orbital apex, superior orbital fissure, cavernous sinus | Meningioma, cavernoma |

| Lacrimal gland, duct system | Pleomorphic adenoma, carcinoma |

| Muscles | Endocrine orbitopathy, rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Preseptal, lid | Lymphomas, infections, lipoma |

Surgical Techniques

Supraorbital Orbitotomy

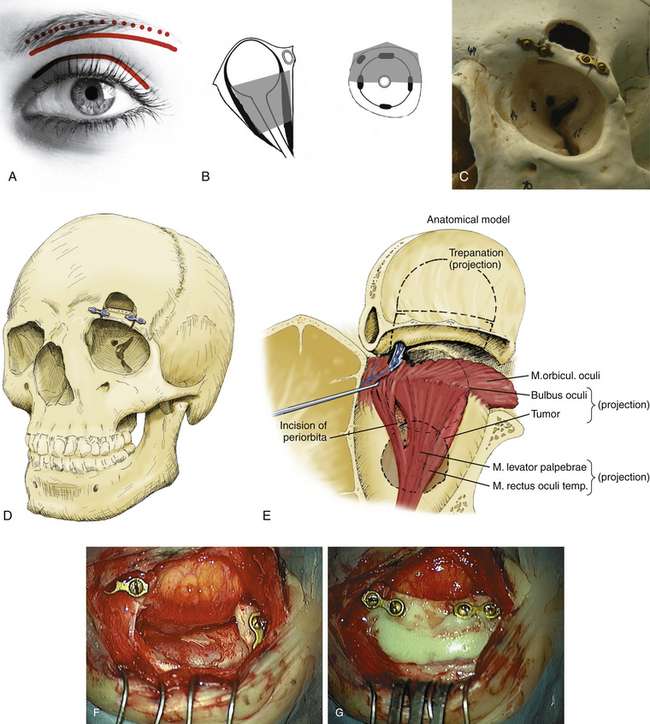

The more lateralized supraorbital approach has been used by neurosurgeons for vascular lesions of the anterior segment of the Circle of Willis and some tumorous lesions from the intradural side during the last two decades (Fig. 51-1).19

Eyebrow incision may also be used for a transperiostal approach to the superior orbit (Table 51-2) (Fig. 51-1A).20,21 Lesions are approached by simple skin incisions of 4 cm along the orbital rim (Fig. 51-1A). After detachment of the periosteum, the supraorbital nerve is dissected and the periorbita is exposed. An osteotomy of the middle part of the supraorbital rim is performed using a reciprocating saw. Miniplates are fitted on both sides of the orbital rim (Fig. 51-1C to G). A small 2 × 3 cm frontobasal osteoclastic trepanation is carried out respecting the lateral border of the frontal sinus (Fig. 51-1C to E). In case of accidental opening of the frontal sinus, the mucous tissue is removed and the tear is closed with subcutaneous fat and fibrin glue. The basal dura of the frontal lobe is pushed away and the orbital roof is removed (Fig. 51-1F). The periorbita is opened and the levator palpebrae and superior rectus muscles are identified (Fig. 51-1E). In deeper intraconal lesions, three self-retaining retractors are positioned in the orbital fat; the tumor is exposed and removed. In extraconal tumors no spatula are necessary. There is no limitation of size of the tumor. The angle of approach allows tumor removal far behind the globe with minimal manipulation of brain and orbit. The surgical corridor is quite broad (3 to 3.5 cm). Finally, the periorbita is closed with sutures in intraconal lesions. In extraconal lesions the periorbita is partially resected and replaced by a dural patch, fixed with fibrin glue. The orbital rim is replaced and fixed by miniosteosynthesis (Fig. 51-1G). The frontobasal trepanation is filled with polymethyl-methacrylate. The orbital roof is not reconstructed. The muscular and subcutaneous layers are closed with interrupted sutures. A small suction drain is placed for 1 day and the skin is closed with a reabsorbable 6-0 suture. Two weeks postoperatively, the cosmetic result is good.

The supraorbital approach can be used in all kinds of intra- and extraconal pathologies that are located cranially to the optic nerve (Fig. 51-1B). It combines the extracranial approach in the eyebrow with the advantages of a frontobasal craniotomy. Thus, it is a mixed approach between the purely extracranial and transcranial approaches. The main advantages are only minimal orbital and brain retraction and it also is not limited by the size of the lesion. The only drawback consists in temporary hypaesthesia in the territory of the supraorbital nerve.

The eyelid crease approach (Fig. 51-1A) is useful for biopsies of lacrimal gland lesions, such as lymphoma, sarcoidosis, or pseudotumor.22 Superior extraconal lesions can be reached via a supraorbital or sub-brow incision. Larger extra- and intra-conal lesions require a superior supraorbital approach with an osteotomy as described above.

Lateral Orbitotomy

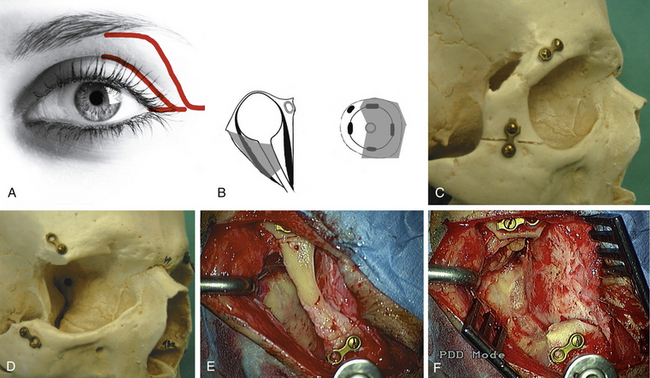

Lateral orbitotomy provides excellent exposure of the temporal compartment of the orbit and it is indicated for well defined periorbital and intraconal tumors which are located lateral, dorsal and basal to the optic nerve (Table 51-2) (Fig. 51-2B).20 It is useful for lacrimal gland tumors, retrobulbar lesions, such as cavernomas, and can be extended for posterior lesions.

In the past, the skin incision started superiorly and laterally in the eyebrow and was extended posteriorly along the zygomatic bone (Fig. 51-2A). Nowadays, the incision is usually smaller and runs along the lid crease towards the corner of the eye to the lateral canthus or even lateral to it (Fig. 51-2A). Then the temporalis fascia is incised, beginning at the midportion of the frontozygomatic bone and extending posteriorly the length of the skin incision. A reciprocating saw is used to incise the lateral rim of the orbit above the zygomaticofrontal suture line and inferiorly at the superior margin of the zygomatic arch (Fig. 51-2C and E). During the osteotomy the globe is protected with a retractor. The anterior edge of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone may be further reduced with rongeurs (Fig. 51-2D and F). The lateral orbit can be approached between the superior and lateral rectus muscles. Finally, a patch of artificial dura is placed to avoid a prolapse of the temporalis muscle into the orbit. Then the frontozygomatic bone is closed using plate and screw fixation. Alternatively, the bone may be held in position by nonabsorbable 4-0 nylon sutures. The periorbita and the slip of the temporalis muscle and periosteum are attached to the lateral orbital margin with 4-0 vicryl sutures.

There are numerous modifications of this lateral approach. The lateral canthothomy (Fig. 51-2A) presents the approach with the smallest incision, sufficient for lateral decompression in endocrine orbitopathy. An osteotomy is not required in all cases. Several anterior approaches through an eyelid crease incision, supraorbital or sub-brow incision are available to approach the anterior third of the orbit.22

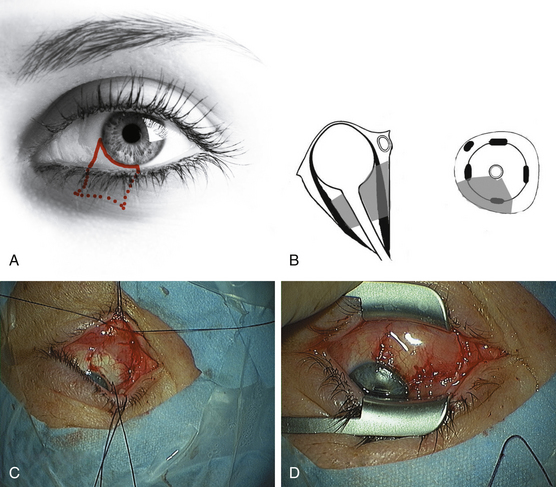

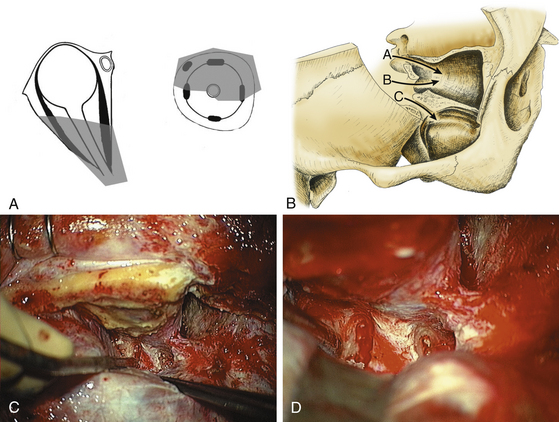

Transconjunctival Approaches

The inferior transconjunctival approach17,23 is restricted to basal and medial intra- and extraconal tumors (Fig. 51-3A and B) (Table 51-2). Following antiseptic preparation, the eyelids held apart, the conjunctiva is incised inferiorly along the corneal edge and the flap created thereby is opened in a caudal direction (Fig. 51-3A and C). The inferior rectus muscle is hooked with a suture and retracted laterally, and the inferior oblique muscle is hooked and retracted caudally. After a superficial preparation and dissection of the layers of connective tissue and orbital fat, the lesion surface can be seen and approached. Due to the small access the tumor is removed piecemeal. After hemostasis, the inferior rectus muscle is released and the conjunctiva is closed with 8 to 10/0 suture (Fig. 51-3D). Limits of the transconjunctival approach are inability to deal with deep intraconal lesions and lesions of the apex (Fig. 51-3B). The advantage is that even masses larger than the eyeball can be removed transconjunctivally without bone destruction and without scars.

Subciliary and transcutaneous lower lid incisions are alternatives to access the inferior orbital rim and floor (Fig. 51-4). The medial transconjunctival approach with release of the insertion of the medial rectus muscle and readapt ion at its ends is used by our ophthalmologists to access the medial anterior orbit for biopsy or fenestration of the optic nerve sheath in pseudotumor cerebri. The transcaruncular approach is an alternative to reach the extraconal medial orbital wall and may be combined with the transconjunctival approach for repair of large medial orbital wall fractures.24

Transantral Approach

The transantral approach18 is performed by ENT surgeons to deal with basal intra- and extra-conal lesions in direct contact to the sinus (Table 51-2). The canine fossa is infiltrated for hemostasis and incised. The mucosa of the mouth is elevated from the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus. An osteotomy is made into the anterior wall with an osteotome and mallet. Using a Kerrison punch, the anterior wall is removed. Any manipulation of the infraorbital neurovascular bundle should be avoided. The bone can be removed up to the orbital rim to provide visualization. The medial orbital floor is removed under preservation of the infraorbital nerve. Then the medial wall and the inferior aspect of the orbital apex are removed. A longitudinal incision of the periorbita is made. Today, endoscopic endonasal approaches are used to approach the medial and inferomedial orbit.25

Transcranial Approaches

Pterional Approach

The pterional approach is a standard operation well described in the literature.26 This approach provides an excellent view of the superior and lateral aspects of the posterior orbit and the optic canal as well as the superior orbital fissure and the anterior temporal fossa (Fig. 51-5A) (Table 51-2). The upper part of the medial orbit can also be exposed. If necessary, the ipsilateral orbital canal can be opened (Fig. 51-5B).

Extradural Pterional Approach

The extradural pterional approach12,27 is an excellent approach to tumors near the superior and inferior orbital fissure and the cavernous sinus (Fig. 51-5B).

Example: Endocrine Orbitopathy, Neurosurgical Approach

This approach provides good access to the superior and lateral walls, facilitates adequate proptosis reduction without induction of double vision, relieves the pressure at the orbital apex, allows decompression of the superior orbital fissure and optic canal, and leaves only scars behind the hair line. This approach is an alternative to other two- or three-wall decompressions and should be taken into consideration in patients with severe ophthalmopathy at greatest risk for permanent visual disability if left untreated.27

Example: Spheno-Orbital Meningioma

The hyperostotic bone is drilled away until the normal shape of the bone (compared with the contralateral side) is remodeled.28 The craniotomy is usually extended to the middle of the orbital rim and the dura mater is dissected from the sphenoid bone. The first steps of the operation are entirely extradural and involve drilling the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone down to the superior orbital fissure (Fig. 51-5C and D) and the bone of the lateral orbital wall down to the foramen rotundum until the beginning of the inferior orbital fissure is exposed. Then a partial anterior clinoidectomy is performed, and the optic canal is unroofed extradurally (Fig. 51-5C and D) whenever tumor involvement is present. The extent of orbital access is tailored for each individual patient. The periorbita is only opened if there is tumor infiltration of intraorbital structures. The lateral periorbital tumor is dissected from the beginning of the superior orbital fissure to the annulus of Zinn and intraorbitally to the superior rectus and levator muscles or the lateral rectus muscle. In cases of infiltration of the ocular muscles, only the exophytic tumor is removed and muscles are not resected. Usually, the tumor is located only in the lateral and/or superior region. Following resection of the anterior temporal bone, the intracranial tumor is removed. Opening of the dura over the cavernous sinus is not recommended in patients without cranial neuropathy. The basal dura is excised as far as possible up to the superior orbital fissure and the optic canal.

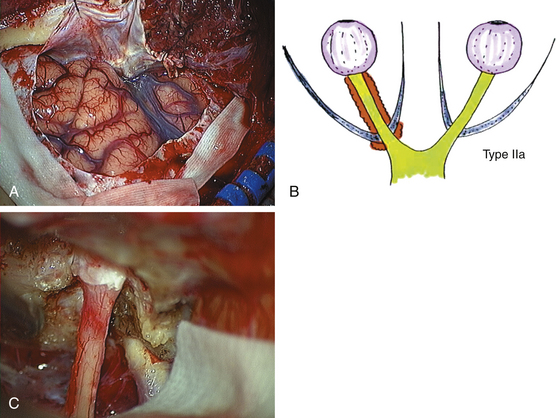

Intradural Pterional Approach

Example: Optic Nerve Sheath Meningioma

For intradural procedures, the sylvian fissure is routinely opened (Fig. 51-6A and B).29 The basal cisterns are incised to drain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The ipsilateral optic nerve and carotid artery are identified and the intracranial tumor is first coagulated and resected along the dura around the optic canal. Preservation of the small feeding vessels between the carotid artery and the optic nerve is important and can be reached by sucking the tumor within the arachnoidal plane. At this step mainly irrigation instead of coagulation should be used. The ipsilateral optic canal should always be opened (Fig. 51-6C). We favor early lateral opening of the dural part of the optic canal to avoid narrowing of the optic nerve through this band. The dura is resected around the optic canal and the bony optic canal is decompressed. The drilling should begin laterally until the floor of the optic canal is reached to prevent any contact to the nerve. Finally, the optic canal is unroofed. In case of lacerating the medially located sphenoid sinus or ethmoidal cells, subcutaneous tissue with fibrin glue is inserted. The tumor around the optic nerve and the dura is carefully removed (Fig. 51-6C). In tumors infiltrating the nerve, resection is limited to the exophytic part. In blind patients with disfiguring painful proptosis, a prechiasmatic trans-section of the optic nerve is performed intradurally and the intraorbital part is removed as well. The intraorbital optic nerve is trans-sected just behind the globe and deep in the apex.

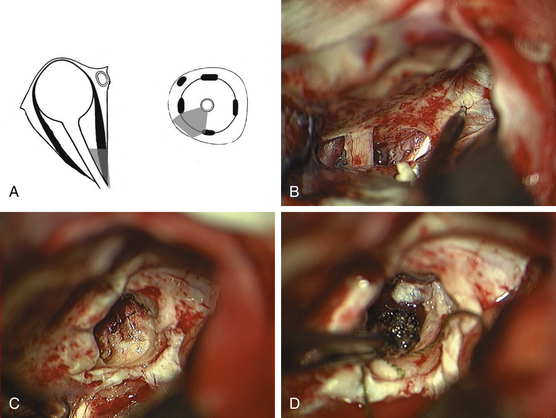

Contralateral Pterional Approach

The contralateral pterional approach is required for lesions of the posterior medial portion of the orbit, located inferior and medial to the optic nerve (Fig. 51-7A).7,20 A standard pterional approach is performed. The proximal sylvian fissure is opened. The sphenoid plane is reached intradurally subfrontally, and both optic nerves and the optic chiasm are visualized. Neuronavigation should be used to define the entrance point at the sphenoid plane and a rectangular patch of dura is removed over this area (Fig. 51-7B). Using a diamond drill, the sphenoid sinus and posterior ethmoidal cells are unroofed and its mucous membrane is exposed (Fig. 51-7C). Care must be taken not to injure the membrane, but rather to dissect it from the bone and to push it anteriorly into the ethmoidal sinus. The posterior medial wall of the contralateral orbit is then exposed with a diamond drill. The periorbita is incised. Between the superior oblique and medial rectus muscles, the lesion can be identified, and dissected carefully from the optic nerve (Fig. 51-7D). Therefore, the axis of the optic nerve should be visualized in extension from the contralateral intradural entrance point to the intraorbital course. After resection, abdominal fat is packed into the sinuses with fibrin glue. The sphenoid sinus is then sealed with a patch of lyophilized dura.

Orbitozygomatic Approach

The combined pterional and orbitozygomatic approach may be useful in selected cases to access extensive tumors of the lateral and laterobasal orbit and orbital apex and tumors extending from the orbit to the superior orbital fissure and temporal fossa.30

There is an ongoing discussion about one-piece versus two-piece orbitozygomatic craniotomy.31 The two-piece orbitozygomatic craniotomy allows for more extensive orbital roof removal and better visualization of the basal frontal lobe.

Surgical Adjuvants

Neuronavigation became a standard procedure in neurosurgery. Accuracy improved due to improved software and registration processes, as well as framework became less complicated. Neuronavigation and more recent modalities at our center in Heidelberg such as intraoperative CT and MR imaging have helped us in the surgical management of difficult orbital apical tumors and are recommended in the contralateral pterional approach to localize small lesions in the apex in an operative distance about 11 to 13 cm from the entrance at the skull to the lesion. Neuronavigation in other intraconal lesions sometimes offers little advantage due to the dissection and dislocation of the orbital fat. However, neuronavigation is useful in defining the dural opening in small lesions within the superior orbital fissure approached via an ipsilateral extradural pterional way. Instruments such as drills and suction may be used as localizing wands with neuronavigation. More than one image localizer can be used at a time. Neuronavigation is often used in endoscopic cases. Endoscopic techniques have evolved dramatically and are effective in approaching the ethmoidal or maxillary sinuses. In the past, endoscopic use in orbital surgery was limited to optic canal decompression and thyroid decompression. This minimally invasive endoscopic surgery has progressed to a “maximally invasive endoscopic” surgery of the skull base in some centers.

Discussion

Operative Approaches

The choice of approach depends on the location, size, demarcation, and histologic type of the lesion. The least traumatic approach should be chosen. The procedures that can be performed range from open biopsies for confirmation of a diagnosis to the subtotal resection of diffusely infiltrating processes with preservation of function and the complete excision of well-circumscribed lesions. Very extensive surgery, with wide excision of bone followed by complicated reconstructive techniques, is rarely necessary. In general, open operations in the orbit are performed by one of two types of approach: transcranial or direct extracranial (Table 51-2).1,18,32–37

A transcranial approach is preferable for processes extending behind the orbit into the cranial cavity or located in the optic canal or the superior orbital fissure.20,28 A classic pterional approach is a standard technique and is also used by the authors for orbital apex tumors.38 An exclusively extradural pterional approach can be used to decompress the optic nerve in the optic canal and superior orbital fissure, as well as for tumor biopsy or resection.12 Usually, a subfrontal approach with significant brain retraction is not necessary for intraorbital tumors. However, there is an indication for this approach in large periorbital tumors with secondary orbital involvement.

Processes located exclusively within the orbit can be reached by a wide variety of relatively noninvasive extracranial approaches, including lateral orbitotomy,2,39 the transethmoidal40–42 and transconjunctival approaches,7,17,23,43 and the frontal-sinusoidal approach.1,44

Lateral Orbitotomy

The basic approach to tumors lateral to the optic nerve is the lateral orbitotomy. This approach is useful for well-circumscribed periorbital and intraconal tumors and for tumors located dorsally, basally, and laterally to the optic nerve, as well as for tumors of the lacrimal gland. Tumors of the orbital apex or located medial to the optic nerve should not be operated on via this approach. Shields and Shields36 describe a less extensive superolateral orbitotomy as an alternative to this lateral orbitotomy to remove tumors located laterally in the orbit. Carta et al.39 advocated a posterolateral orbitotomy for the orbital apex. This approach, through a small opening on the orbital and temporal portions of the greater wing of the sphenoid, allowed adequate exposure of the orbital apex. Goldberg et al.45 presented a deep transorbital approach to the apex and cavernous sinus. By enlarging the bony incision of a classic lateral orbitotomy to include a generous marginotomy and removing the deep sphenoid wing up to the superior orbital fissure, they obtained good exposure of the lateral orbital apex. We recommend a standard pterional approach to orbital apex tumors.

Transconjunctival Approach

The authors favor a transconjunctival approach for basal, medial intra- and extra-conal tumors, and particularly for biopsies of intraconal processes. Even masses larger than the eyeball can be removed transconjunctivally without bone destruction and an excellent cosmetic result.23 Gdal-On and Gelfand43 also favor a transconjunctival extraction for intraconal cavernoma. About 10% of the patients had to undergo secondary lateral orbitotomy, because the tumor could not be identified via the transconjunctival approach. For small lesions, image guidance is required.23 The transcaruncular approach is available for medial orbital fracture repair.24

Transantral Approach

Basal lesions in direct contact to the sinus may be approached transantrally. Kennerdell et al.44 used a posterior inferior orbitotomy through the maxillary sinus to treat patients with orbital apex tumors between the optic nerve and inferior rectus. Mir-Salim and Berghaus42 performed an endonasal microsurgical transethmoidal access to remove an intraconal hemangioma. However, this is a long operative distance with limited view. Herman et al.40 reported on a transnasal endoscopic approach in a case of inferomedial and posterior intraconal cavernoma. Endoscopic endonasal techniques became more frequent to approach the medial and inferomedial orbit.25,46

Supraorbital Approach

Our new supraorbital approach21 occupies an intermediate position between the extra- and trans-cranial approaches. Well-circumscribed processes superior to the optic nerve can be reached either intra- or extra-conally through an eyebrow incision. The supraorbital approach is particularly useful for the removal of cavernomas and schwannomas.20 The earliest technical note of a supraorbital approach via a bicoronal flap, Jane et al. described a burr hole behind the zygomatic process with detached temporal muscle in 1982.47 Maus and Goldman48 used a transorbital craniotomy through a suprabrow approach to remove a cavernoma of the orbital apex. Our supraorbital approach is comparable to this approach but less invasive considering the extent of bone removal. The major advantage is that only a small transient resection of the upper supraorbital rim is necessary to create a focused surgical corridor. Brain and orbital manipulations are minimized. The size of the lesion is not a limiting factor. This extradural approach is also well tolerated in elderly patients. The hypaesthesic area in the territory of the supraorbital nerve usually recovers within 7 months. The cosmetic result compared to the lateral orbitotomy is much better, hiding the scar completely within the eyebrow. This new approach presents quite a useful addition to the variety of currently utilized operative techniques.

Pterional Approaches

The ipsilateral pterional approach is our standard neurosurgical approach to tumors of the superior orbital fissure, optic canal, and orbital apex. Tumors located dorsal to the optic nerve, lateral, extra- and intra-conal tumors can be easily reached. Only tumors medial and basal to the optic nerve should not be operated on via this approach. These lesions in the posterior intraconal space can also be approached by a pterional contralateral way.7 This route leads from the contralateral side through the sphenoid and ethmoidal sinus without opening the mucous membrane. This approach provides excellent exposure and straight access to the lesion. A transethmoidal operation has more limited space and an unfavorable angle for dissection.

Tumors of the superior orbital fissure such as cavernomas or neurofibromas are best approached extradurally. Detailed anatomic knowledge is essential to perform a lateral-to-medial dissection and incise the periorbital between the lateral and superior rectus muscle.12,16

The authors’ classification scheme38 distinguishes intraorbital (type 1) from intracanalicular (type 2) optic sheath meningiomas and from those that are both intraorbital and intracanalicular (type 3). When an intraorbital tumor (type 1) begins to affect visual acuity, it should be treated with radiation at first,49–51 and any large exophytic tumor mass should be resected. For type 2 tumors, surgical decompression of the optic canal can stave off the impending loss of vision. Type 3 tumors growing toward the intracranial compartment are best treated with extradural decompression of the optic canal, intracranial tumor resection, and postoperative irradiation of the intraorbital portion.38

Al-Mefty O., Fox J.L. Superolateral orbital exposure and reconstruction. Surg Neurol. 1985;23:609-613.

Bejjani G.K., Cockerham K.P., Kennerdell J.S., Maroon J.C. A reappraisal of surgery for orbital tumors. Part I: extraorbital approaches. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;10(5):E2.

Berke R.N. Modified Krönlein operation. AMA Arch Ophth. 1954;51:609-632.

Cockerham K.P., Bejjani G.K., Kennerdell J.S., Maroon J.C. Surgery for orbital tumors. Part II: transorbital approaches. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;10(5):E3.

Dandy W. Results following the transcranial operative attack on orbital tumors. Arch Ophthalmol. 1941;25:191-216.

Dolenc V.V. Direct microsurgical repair of intracavernous vascular lesions. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:824-831.

Hassler W.E., Eggert H. Extradural and intradural microsurgical approaches to lesions of the optic canal and the superior orbital fissure. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1985;74:87-93.

Hassler W.E., Meyer B., Rohde V., Unsöld R. Pterional approach to the contralateral orbit. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:552-554.

Hassler W., Schick U. The supraorbital approach—a minimally invasive approach to the superior orbit. Acta Neurochir. 2009;151:605-612.

Hejazi N., Hassler W., Farghaly F. Transconjunctival microsurgical approach to the orbit: a retrospective preliminary review and analysis of experience with the first 15 operative cases. Neurosurg Q. 1999;9:197-208.

Housepian E.M. Microsurgical anatomy of the orbital apex and principles of transcranial orbital exploration. Clin Neurosurg. 1978;25:556-573.

Jane A.J., Sung Park T., Pobereskin L.H., et al. The supraorbital approach: technical note. Neurosurgery. 1982;11:537-542.

Kennerdell J.S., Maroon J.C., Malton M.L. Surgical approaches to orbital tumors. Clin Plast Surg. 1988;15:237-282.

Krönlein R. Zur Pathologie und operativen Behandlung der Dermoidzysten der Orbita. Beitr Klin Chir. 1889;4:149-163. (German)

Mauriello J.A., Flanagan J.C. Surgical approaches to the orbit. In: Mauriello J.A., Flanagan J.C. Management of orbital and ocular adnexal tumors and inflammations. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 1990:149-169.

Naffziger H.C. Exophthalmos. Some principles of surgical management from the neurosurgical aspect. Am J Surg. 1948;75:25-41.

Rhoton A.L., Natori Y. Microsurgical Anatomy and Operative Approaches. In: The Orbit and Sellar Region. New York and Stuttgart: Thieme; 1996:208-308.

Rohde V., Schaller K., Hassler W. The combined pterional and orbitocygomatic approach to extensive tumours of the lateral and latero-basal orbit and orbital apex. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;132:127-130.

Schick U., Bleyen J., Bani A., Hassler W. Management of meningiomas en plaque of the sphenoid wing. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:208-214.

Schick U., Dott U., Hassler W. Surgical management of meningiomas involving the optic nerve sheath. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:951-959.

Shields J.A., Shields C.L., Scartozzi R. Survey of 1264 patients with orbital tumors and simulating lesions: The 2002 Montgomery Lecture, part 1. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:997-1008.

Turbin R.E., Pokorny K. Diagnosis and treatment of optic nerve sheath meningioma. Cancer Control. 2004;11:334-341.

Yasargil M.G., Fox J.L. The microsurgical approach to intracranial aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 1975;3:7-14.

1. Shields J.A., Shields C.L., Scartozzi R. Survey of 1264 patients with orbital tumors and simulationg lesions: the 2002 Montgomery Lecture, part 1. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:997-1008.

2. Krönlein R. Zur Pathologie und operativen Behandlung der Dermoidzysten der Orbita. Beitr Klin Chir. 1889;4:149-163.

3. Berke R.N. Modified Krönlein operation. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1954;51:609-632.

4. Kennerdell J.S., Maroon J.C., Malton M.L. Surgical approaches to orbital tumors. Clin Plast Surg. 1988;15:237-282.

5. Niho S., Niho M., Niho K. Decompression of the optic canal by the transethmoidal route and decompression of the superior orbital fissure. Can J Ophthalmol. 1970;5:22-40.

6. Colohan A.R., Jane J.A., Newman S.A., et al. Frontal sinus approach to the orbit. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:811-813.

7. Hassler W., Schaller C., Farghaly F., et al. Transconjunctival approach to a large cavernoma of the orbit. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:859-862.

8. Dandy W. Results following the transcranial operative attack on orbital tumors. Arch Ophthalmol. 1941;25:191-216.

9. Housepian E.M. Microsurgical anatomy of the orbital apex and principles of transcranial orbital exploration. Clin Neurosurg. 1978;25:556-573.

10. Naffziger H.C. Exophthalmos. Some principles of surgical management from the neurosurgical aspect. Am J Surg. 1948;75:25-41.

11. Yasargil M.G., Fox J.L. The microsurgical approach to intracranial aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 1975;3:7-14.

12. Hassler W.E., Eggert H. Extradural and intradural microsurgical approaches to lesions of the optic canal and the superior orbital fissure. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1985;74:87-93.

13. Dolenc V.V. Direct microsurgical repair of intracavernous vascular lesions. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:824-831.

14. Dolenc V.V. Anatomy and Surgery of the Cavernous Sinus. Wien, New York: Springer; 1989.

15. Hassler W.E., Meyer B., Rohde V., Unsöld R. Pterional approach to the contralateral orbit. Neurosurg. 1994;34:552-554.

16. Bejjani G.K., Cockerham K.P., Kennerdell J.S., Maroon J.C. A reappraisal of surgery for orbital tumors. Part I: extraorbital approaches. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;10(5):E2.

17. Hejazi N., Classen R., Hassler W. Orbital and cerebral cavernomas: comparison of clinical, neuroimaging and neuropathological features. Neurosurg Rev. 1999;22:28-33.

18. Mauriello J.A., Flanagan J.C. Surgical approaches to the orbit. In: Mauriello J.A., Flanagan J.C. Management of orbital and ocular adnexal tumors and inflammations. Berlin, Heidelberg, and New York: Springer; 1990:149-169.

19. Reisch R., Perneczky A. Ten-year experience with the supraorbital subfrontal approach through an eyebrow skin incision. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:242-255.

20. Schick U., Dott U., Hassler W. Surgical treatment of orbital cavernomas. Surg Neurol. 2003;60:234-244.

21. Hassler W., Schick U. The supraorbital approach—a minimally invasive approach to the superior orbit. Acta Neurochir. 2009;151:605-612.

22. Cockerham K.P., Bejjani G.K., Kennerdell J.S., Maroon J.C. Surgery for orbital tumors. Part II: transorbital approaches. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;10(5):E3.

23. Hejazi N., Hassler W., Farghaly F. Transconjunctival microsurgical approach to the orbit: a retrospective preliminary review and analysis of experience with the first 15 operative cases. Neurosurg Q. 1999;9:197-208.

24. Lee C.S., Yoon J.S., Lee S.Y. Combined transconjunctival and transcaruncular approach for repair of large medial orbital wall fractures. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:291-296.

25. Düz B., Secer H.I., Gonul E. Endoscopic approaches to the orbit: a cadaveric study. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2009;52:107-113.

27. Schick U., Hassler W. Decompression of endocrine orbitopathy via an extended extradural pterional approach. Acta Neurochir. 2005;147:143-149.

28. Schick U., Bleyen J., Bani A., Hassler W. Management of meningiomas en plaque of the sphenoid wing. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:208-214.

29. Schick U., Dott U., Hassler W. Surgical management of meningiomas involving the optic nerve sheath. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:951-959.

30. Rohde V., Schaller K., Hassler W. The combined pterional and orbitocygomatic approach to extensive tumours of the lateral and latero-basal orbit and orbital apex. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;132:127-130.

31. Tanriover N., Ulm A.J., Rhoton A.L.Jr., et al. One-piece versus two-piece orbitozygomatic craniotomy: quantitative and qualitative considerations. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(4 suppl 2):ONS229-ONS237.

32. Al-Mefty O., Fox J.L. Superolateral orbital exposure and reconstruction. Surg Neurol. 1985;23:609-613.

33. Delfini R., Missori P., Tarantino R. Primary benign tumors of the orbital cavity: comparative data in a series of patients with optic nerve glioma, sheath meningioma or neurinoma. Surg Neurol. 1996;45:147-154.

34. Gunalp I. Gunduz. Vascular tumors of the orbit. Doc Ophthalmol. 1995;89:337-345.

35. Natory Y., Rhoton A.L. Transcranial approach to the orbit. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:78-86.

36. Shields J.A., Shields C. Vascular and hemorrhagic lesions. In: Shields J.A., Shields C. Atlas of Orbital Tumors. Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:45-73.

37. Van der Wal K.G.H., De Visscher J.G.A.M., Boukes R.J., et al. Surgical treatment of proptosis bulbi by three-wall orbital decompression. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:140-142.

38. Schick U., Hassler W. Neurosurgical management of orbital inflammations and infections. Acta Neurochir. 2004;146:571-580.

39. Carta F., Siccardi D., Cossu M., et al. Removal of tumours of the orbital apex via a postero-lateral orbitotomy. J Neurosurg Sci. 1988;42:185-188.

40. Herman P., Lot G., Silhouette B., et al. Transnasal endoscopic removal of an orbital cavernoma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:147-150.

41. Lund V., Larkin G., Fells P., et al. Orbital decompression for thyroid disease: a comparison of external and endoscopic techniques. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:1051-1055.

42. Mir-Salim P.A., Berghaus A. Endonasal, microsurgical approach to the retrobulbar region exemplified by intraconal hemangioma. HNO. 1999;47:192-195.

43. Gdal-On M., Gelfand Y.A. Surgical outcome of transconjunctival cryosurgical extraction of orbital cavernous hemangioma. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1998;29:969-973.

44. Kennerdell J.S., Maroon J.C., Celin S. The posterior inferior orbitotomy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;14:277-280.

45. Goldberg R.A., Shorr N., Arnold A.C., et al. Deep transorbital approach to the apex and the cavernous sinus. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;14:336-341.

46. Karaki M., Kobayashi R., Kobayashi E., et al. Computed tomographic evaluation of anatomic relationship between the paranasal structures and orbital contents for endoscopic endonasal transethmoidal approach to the orbit. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(1 suppl 1):ONS15-ONS19.

47. Jane A.J., Sung Park T., Pobereskin L.H., et al. The supraorbital approach: technical note. Neurosurgery. 1982;11:537-542.

48. Maus M., Goldman H.W. Removal of orbital apex hemangioma using new transorbital craniotomy through suprabrow approach. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;15:166-170.

49. Miller N.R. Primary tumours of the optic nerve and its sheath. Eye. 2004;18:1026-1037.

50. Pitz S., Becker G., Schiefer U., et al. Stereotactic fractionated irradiation of the optic nerve sheath meningioma: a new treatment alternative. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1265-1268.

51. Turbin R.E., Pokorny K. Diagnosis and treatment of optic nerve sheath meningioma. Cancer Control. 2004;11:334-341.