Surgical Anatomy of the Bladder and Ureter

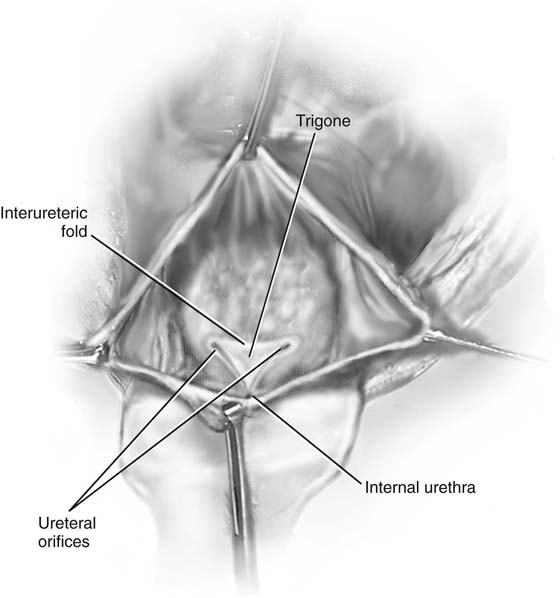

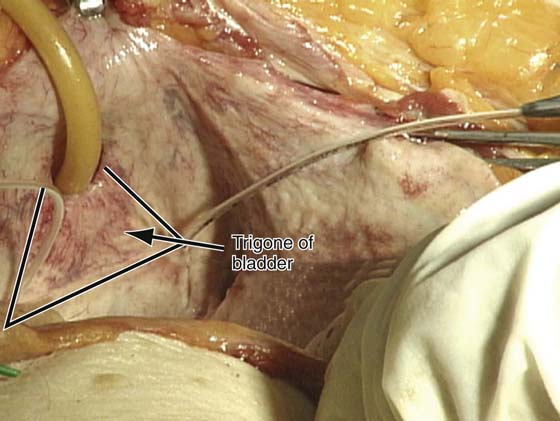

The bladder is a hollow, muscular organ, its main function being that of a reservoir. Secondary to the distensibility of its muscular wall, it has the inherent ability to maintain a low pressure even when fully distended so as to maximum capacity. When empty, the adult bladder lies behind the pelvic symphysis and is a pelvic organ. When full, the bladder rises well above the symphysis and can readily be palpated and percussed. The empty bladder is described as having an apex, a superior surface, two anterior lateral surfaces, a base or posterior surface, and a neck (Figs. 86–1 and 86–2). The apex reaches a short distance above the pelvic bone and ends with a fibrous cord derivative of the urachus, which originally connects the bladder to the allantois. This fibrous cord extends from the apex of the bladder to the umbilicus between the peritoneum and the transversalis fascia. It raises a ridge of peritoneum called the median umbilical ligament. The superior surface is the only surface of the bladder covered by peritoneum. The superior surface of the bladder is in relation to the uterus and the ileum. The base of the bladder faces posteriorly and is separated from the rectum by the uterus and vagina. The anterior lateral surfaces on each side of the bladder are in relation to the obturator internus, levator ani muscles, and pelvic bone (Figs. 86–3 and 86–4). However, the bladder is actually separated from the pelvic bone by the retropubic space (see Chapter 31). The interior of the bladder is completely covered by several layers of transitional epithelium (see Fig. 86–1). A loose underlying connective tissue permits considerable stretching of the mucosa; for that reason, the mucosal lining is wrinkled when the bladder is empty but quite smooth and flat when the bladder is distended. This arrangement exists throughout except over the trigone area, where the mucous membrane is fairly adherent to the underlying musculature of the superficial trigone. This is why the trigone is always smooth whether the bladder is full or empty (see Fig. 86–4).

The ureter is about 28 to 32 cm long in the adult and runs half its course in the abdomen and half in the pelvis after it crosses the iliac vessels (Fig. 86–5). During abdominal or vaginal surgery, the ureter may be inadvertently bruised, lacerated, ligated, partially or completely transected, or mishandled in such a way that the blood supply is disturbed and necrosis develops at a later time. The anatomy of the entire ureter has been reviewed in and Chapter 36 and Chapter 37.

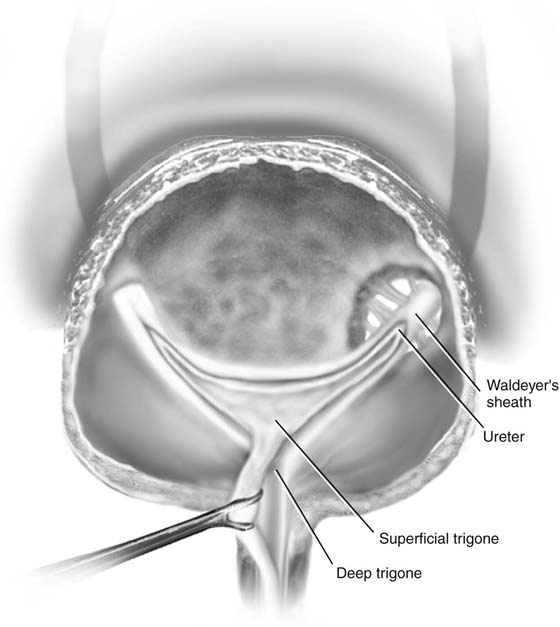

The ureter enters the pelvis by crossing over the iliac vessels where the common iliac artery divides into the external iliac and hypogastric vessels. At this point, the ureter lies medial to the branches of the anterior division of the hypogastric artery and lateral to the peritoneum of the cul-de-sac. It is attached to the peritoneum of the lateral pelvic wall. The ureter passes beneath the uterine artery approximately 1.5 cm lateral to the cervix. As it proceeds more distally, the ureter courses along the lateral side of the uterosacral ligament and enters the endopelvic fascia of the parametrium (cardinal ligament) (Figs. 86–5 through 86–11). The ureter then enters the envelope of the endopelvic fascia and follows the lateral true ligament of the bladder, accompanied by a few vesical vessels and a component of the autonomic pelvic plexus, to run in front of the vagina and enter the bladder base. The intravesical ureter is about 1.5 cm long and is divided into an intramural segment that is totally surrounded by the bladder wall and a submucosal segment (about 0.8 cm long) directly under the bladder mucosa. All the ureteral muscles extend uninterrupted into the base of the bladder and continue as the trigone. The juxtavesical ureter (the distal 3 to 4 cm) as well as the intramural segment of the intravesical ureter is surrounded by a fibromuscular sheath—Waldeyer’s sheath (Fig. 86–12). As this sheath is traced upward, its muscular element gradually fuses with the ureteral musculature and becomes an integral part of the ureteral wall. In this manner, Waldeyer’s sheath proximally fuses with the intrinsic musculature of the ureter and distally acts as an added fixation linking the ureter proper and the detrusor (see Fig. 86–12).

The trigone is composed of superficial and deep layers (see Fig. 86–12). The longitudinal fibers of the intravesical ureter diverge at the ureteral orifice and continue uninterrupted at the base of the bladder as the superficial trigone. Some fibers run across the base of the trigone between one submucosal ureter and the other. The rest fan out and converge at the internal meatus to proceed downward into the urethra in the midline posteriorly. In the female, the same fibers terminate at the level of the external meatus. All the fibers forming Waldeyer’s sheath continue downward uninterrupted into the base of the bladder, forming the deep trigone. The upper fibers proceed medially to meet those from the other side, forming the base of the trigonal structure—the interureteric ridge, or Mercier’s bar. There is muscular communication between the superficial and deep trigone. They can be easily dissected from one another. The two layers of the trigone are in direct continuation with the lower ureter, with no interruption or loss of any of the musculature. One can say that the ureter does not end at the ureteral orifice but continues uninterrupted as a flat sheet instead of a tubular structure.

FIGURE 86–1 Abdominal view of the inside of the urinary bladder. Note the structure of the urinary trigone, ureteral orifices, and interureteric fold, or ridge. Also note the smooth appearance of the trigone and the wrinkled appearance of the mucosal lining of the bladder.

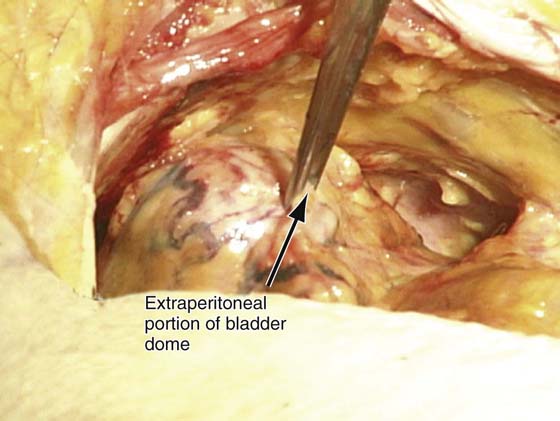

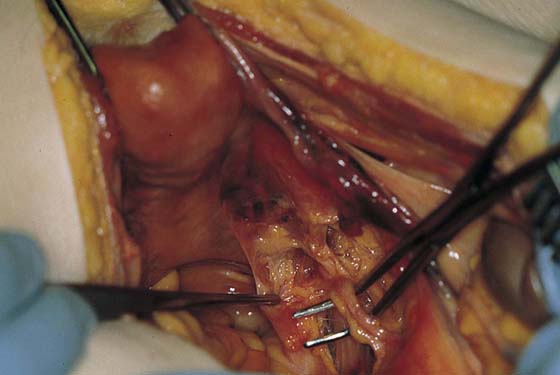

FIGURE 86–2 The bladder from the retropubic space is visualized. The pick-ups are holding the dome of the bladder in its extraperitoneal portion.

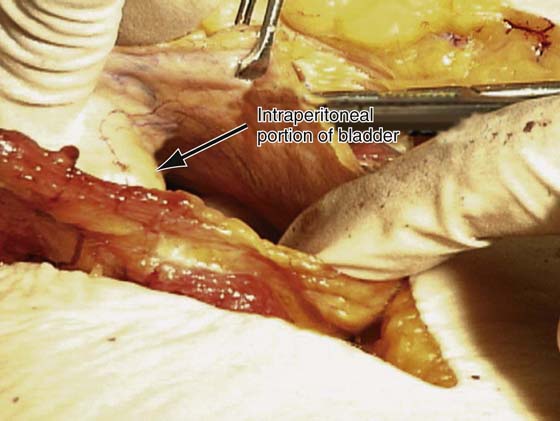

FIGURE 86–3 The peritoneum has been opened and the interperitoneal portion of the bladder is shown.

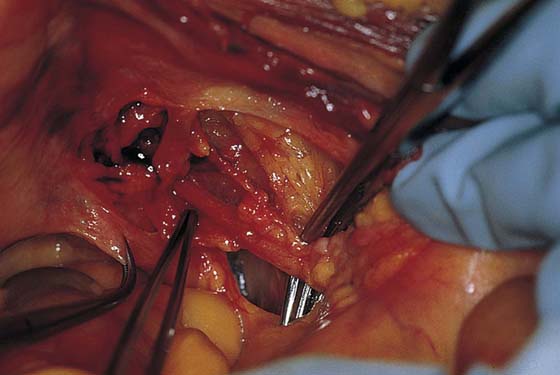

FIGURE 86–4 The bladder has been opened and the trigone of the bladder is shown in this cadaver. Note: Both ureteral orifices have been threaded with a pediatric feeding tube. This figure depicts the normal intravesical anatomy of the bladder and the trigone.

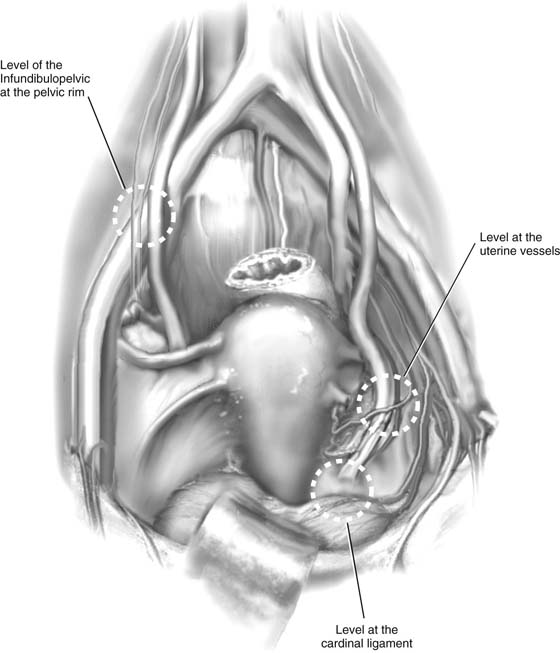

FIGURE 86–5 This drawing shows the anatomy of the pelvic ureter. Circled areas are anatomic sites where the ureter is most likely to be injured during gynecologic surgery.

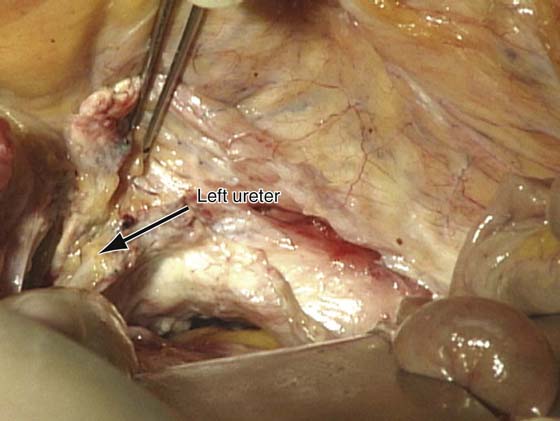

FIGURE 86–6 The relationship of the left ureter to the apex of the vagina is shown.

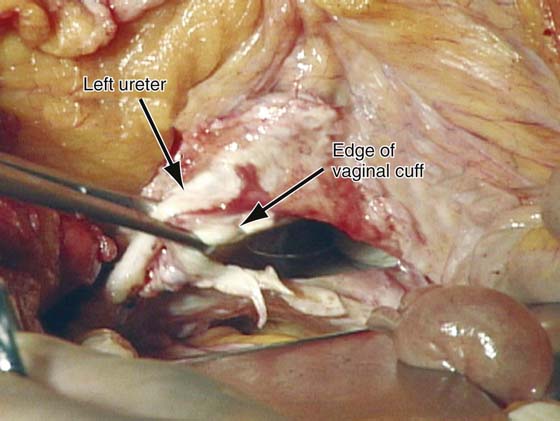

FIGURE 86–7 The vaginal cuff has been opened, and pick-ups have been used to grasp the lateral edge of the vaginal cuff and the left ureter as it enters the urinary bladder. Note the close proximity of the ureter to the vaginal cuff at this anatomic location.

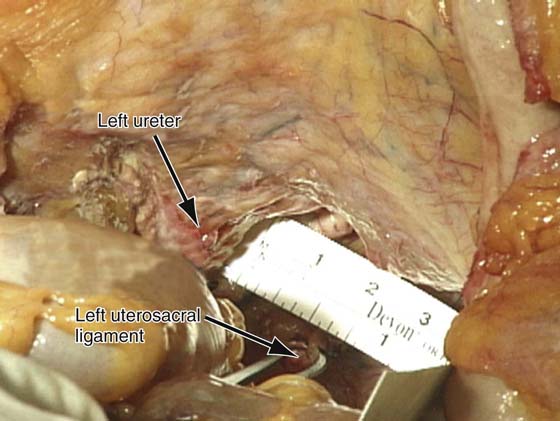

FIGURE 86–8 This figure demonstrates the relationship between the left ureter and the left uterosacral ligament in the lower portion of the pelvis. Note that in this specific cadaver, the ureter was approximately 2 cm lateral to the left uterosacral ligament.

FIGURE 86–9 The relationship of the right ureter to the right uterosacral ligament is shown.

FIGURE 86–10 This figure illustrates the relationship of the right ureter to the right uterosacral ligament at the level of the ischial spine. Note that the distance between the two structures was about 4 cm in this specific cadaver.

FIGURE 86–11 The backs of pick-ups point to where the right ureter enters the fascial tunnel of the cardinal ligament. The right-angle clamp to the left of the pick-ups is on the right uterosacral ligament close to its insertion into the uterus.

FIGURE 86–12 Waldeyer’s sheath connected by a few fibers to the detrusor muscle in the ureteral hiatus. This muscular sheath inferior to the ureteral orifice becomes the deep trigone. The musculature of the ureters continues downward as the superficial trigone.