CHAPTER 75 Surgery: Thoracic Disc Disease

INTRODUCTION

Compared with the cervical and lumbar spine, degenerative thoracic disc pathology is relatively uncommon. When present, however, it can produce symptoms of axial or mechanical back pain, radiculopathy, or myelopathy. Surgery is effective for treating many forms of thoracic disc pathology that have failed nonoperative treatment.

INDICATIONS

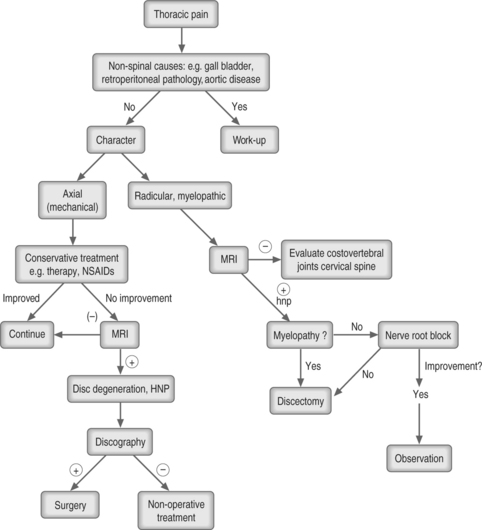

Indications for surgical intervention include myelopathy, progressive neurologic deficit, confirmed radiculopathy, or mechanical axial back pain persisting at an unacceptable level in those who have failed adequate nonsurgical treatment (Fig. 75.1). If surgery is contemplated, it should be directed at the levels with confirmed pathology as seen on axial diagnostic imaging.

Thoracic disc herniations are the most common manifestation of thoracic disc degeneration requiring surgical treatment (Fig. 75.2). With the advent of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) the frequency with which the diagnosis of a herniated disc is made has increased. It is important to remember, however, that thoracic disc herniations can be seen in an otherwise asymptomatic population. Wood et al.1 found, in their study of asymptomatic individuals, that 37% of those studied had at least one herniation, half of whom had multiple protrusions and many with actual deformation of the spinal cord. In addition, because of the relative paucity of classic clinical findings such as those seen with herniations in the lumbar spine, complaints can often be vague, especially when it is principally axial pain. Historically, a large number of other pathologic conditions including not only lumbar disc disease and neurogenic claudication, but also cardiac, abdominal (e.g. gall bladder), intrathoracic pathologies, and even multiple sclerosis have been mistakenly diagnosed. When myelopathy is found, cervical involvement should be evaluated to rule out concomitant pathology.

Making the correct diagnosis begins with MRI, especially for evaluating mechanical back pain. When evaluating spinal cord encroachment, myelography with computed tomography (CT) is another option, but it is invasive, although its sensitivity and specificity are comparable with that of MRI.2,3 CT can also be used to describe calcifications at the disc level, or ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament or ligamentum flavum. Defining the precise pathology is important, as it will often influence the surgical approach. Many feel that obtaining both an MRI as well as a CT-myelogram is indicated for those scheduled for surgery.

In instances where the presentation is less clear – typically mechanical or axial pain – further confirmation of the pathology can be obtained with discographic evaluation. When performed by experienced and skilled technicians, it is a safe and reliable procedure to confirm and locate the site of axial thoracic pain.4,5 It can be especially useful in situations of multiple levels of thoracic pathology with varying grades of disc herniations. A strict contraindication, however, is a large prolapse with spinal cord deformation wherein the instillation of a saline contrast would run the risk of further cord compression. Thus, discography is probably somewhat limited to those situations of smaller or no actual disc protrusion.

TECHNIQUE

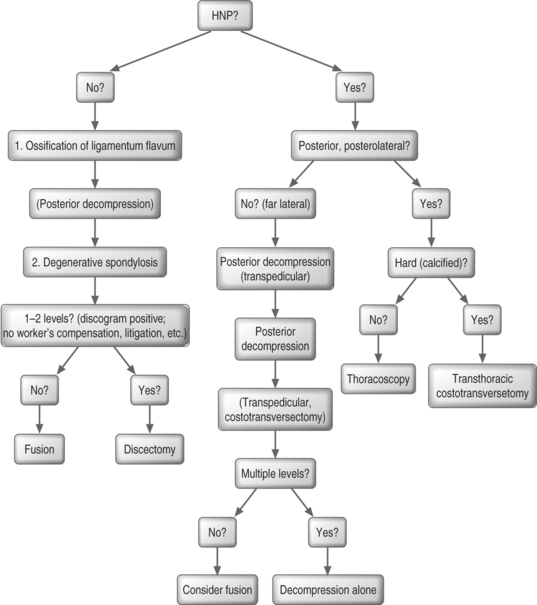

Numerous surgical approaches have been described for the treatment of thoracic disc pathology (Fig. 75.3). In general, a degenerated disc that is believed to be the source of axial back pain can be treated with a subtotal discectomy and interbody fusions. This applies, in the author’s view, to those situations in which the pathology extends over one or two levels. It is the author’s view that for pathology that extends over several levels, a stabilizing posterior instrumented fusion with or without an anterior fusion is an option for axial back pain, in the properly selected individual. Here, discography may well help the decision-making process. For neuropathology due to herniated discs, typically an anterior decompression and fusion is preferred unless the disc is well-confined laterally and accessible posteriorly.

Posterior laminectomies are generally regarded as poor approaches for decompression of an anteriorly compromised spinal canal because of a historically high rate of unimproved or worsened neurological status.6 One review of 135 patients treated with laminectomy noted almost one-third being made worse by the procedure.7

The transthoracic approach is the most straightforward method of decompressing anteriorly based compression of the spinal cord and carries the highest likelihood of achieving neurological improvement with a relatively lower incidence of serious complications.8 The entire disc space can be seen and wide decompression performed without any manipulation of the spinal cord (Fig. 75.4). The chest is entered one or two levels above the herniation via a thoracotomy. The rib head overlying the disc space is removed, followed by removal of the base of the pedicle, allowing visualization of the dura. The posterior third of the adjacent endplates is removed, creating a cavity into which the posterior cortex plus the protruding disc fragment can then be safely pulled and then removed with a curette.

Thoracoscopy is a relatively recent technology which can allow thoracic discectomy,9 fusion with bone graft, if desired, and even instrumentation. Thoracoscopy is best suited for soft (noncalcified) herniations and degenerative discs. It holds the possibility of less morbidity when compared with the traditional transthoracic approach. A thoracic surgeon, well trained in this technique, may be recommended as well as time spent in the training laboratory before beginning. The major advantage of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery is that it avoids a large open thoracotomy with its attendant morbidity – chest wall pain, shoulder dysfunction, longer hospitalization – but the learning curve is large and a direct comparison with open procedures is still lacking. Anand and Regan10 described their experience with 100 patients and felt they were able to achieve clinical results similar to open thoracotomy techniques.

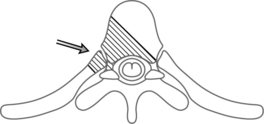

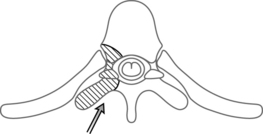

The costotransversectomy approach may be indicated under certain circumstances such as when a disc herniation is in an extremely posterolateral position or when the pathology is in the uppermost thoracic spine, an area sometimes difficult to reach with a transthoracic approach (Fig. 75.5). One to three rib heads as well as the transverse processes are usually removed with this approach, hence the name. Occasionally, the intercostal neurovascular bundles may need to be sacrificed in order to gain exposure. Once adequate visualization is obtained, the technique of decompression and fusion is similar to that of the transthoracic thoracotomy approach. If the herniation is centralized, or intradural, it may be more difficult to visualize across the entire disc with this technique as apposed to the more traditional transthoracic approach. In addition, if the facet is removed during the exposure, one should consider a prophylactic fusion, to prevent possible sagittal plane decompensation.

Fig. 75.5 The approach (arrow) and bony resection (hatched lines) in the costotransversectomy approach.

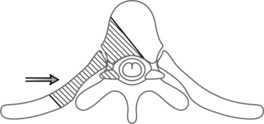

A transpedicular approach is another choice, and although it generally provides less exposure than the transthoracic or costotransversectomy approachs, yet it is suitable for a posterolateral or foraminal herniation (Fig. 75.6). Its advantage is that it avoids a thoracotomy, although the actual access to the disc is still somewhat limited.

Finally, performing surgery at the wrong level can be a common error when treating thoracic disc pathology, whether the procedure is open or with thoracoscopy. The thoracic anatomy can be more variable than in the lumbar or cervical spines with different numbers of vertebrae and ribs. A chest radiograph is important in the preoperative work-up to be able to count the ribs and verify the correct level. The MRI has to be just as accurate and should, if possible, include sagittal plane images that allow counting down to the sacrum for level verification. A myelogram can be very helpful, identify focal protrusions if present, and also allow counting of ribs to accurately note the pathologic level.

1 Wood KB, Garvey TA, Gundry C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the thoracic spine: evaluation of asymptomatic individuals. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1995;77:1631-1638.

2 Thornbury JR, Fryback DG, Turski PA, et al. Disk-caused nerve compression in patients with acute low-back pain: diagnosis with MR, CT myelography, and plain CT. Radiology. 1993;186(3):731-738.

3 Anderson RE. Magnetic resonance imaging versus computed tomography – which one? Postgrad Med. 1989;85(3):79-83. 86–87

4 Wood KB, Schellhas KP, Garvey TA, et al. Thoracic discography in healthy individuals. A controlled prospective study of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals. Spine. 1999;24(15):1548-1555.

5 Schellhas KP, Pollie SR, Dorwat RH. Thoracic discography: a safe and reliable technique. Spine. 1994;19:2103-2109.

6 Bohlman HH, Freehafter A, Dejak J. The results of treatment of acute injuries of the upper thoracic spine with paralysis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1985;67:360-369.

7 Fessler RG, Sturgill M. Complications of surgery for thoracic disc disease [Review]. Surg Neurol. 1998;49(6):609-618.

8 Bohlman HH, Zdeblick TA. Anterior excision of herniated thoracic discs. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1988;70:1038-1047.

9 Regan JJ, Ben-Yeshay A, Mack M. Video-assisted thorascopic excision of herniated thoracic disc: description of technique and preliminary experience in the first 29 cases. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11(3):183-191.

10 Anand N, Regan JJ. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for thoracic disc disease. Spine. 2002;27(8):871-879.