Surgery for Vulvar Vestibulitis Syndrome (Vulvodynia)

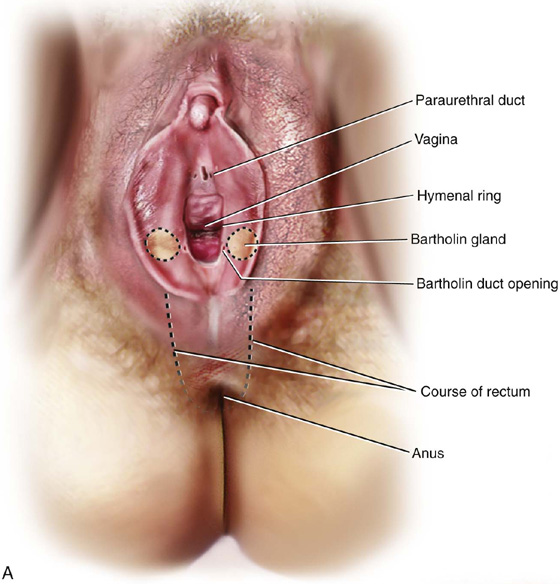

Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome is a disorder of unknown cause that produces erythema, hyperesthesia, and extreme discomfort to light pressure, principally around the Bartholin duct and the underlying Bartholin gland. Although other vulvar mucous glands (i.e., the paraurethral and minor vestibular glands) may be sensitive to touch, major signs and symptoms are related mainly to Bartholin glands (Fig. 67–1A through C). Afflicted women complain of a burning raw feeling during and after sexual intercourse to such a degree that apareunia eventuates. All patients in whom this diagnosis is made should undergo a conservative regimen over a period of 2 to 4 months. If conservative treatment does not lead to substantial amelioration of symptoms and an objective decrease in erythema and light touch–induced pain, then the patient should be offered the surgical option (Fig. 67–2).

Surgery for the treatment of vestibulitis presents two options. The first and simpler procedure is vestibulectomy with or without excision of the paraurethral duct(s) and vaginal advancement. This operation excises the inflamed tissue(s) to include depth into Colles’ fascia and margins to Hart’s line, as well as removal of a centimeter of the lower vagina. The advantage of this operation is shortened operative time (1.5 hours or less) and less morbidity in the form of postoperative pudendal neuralgia (Fig. 67–3A through E).

The alternative operation includes radical excision of the Bartholin glands, vestibulectomy, and vaginal advancement. This operation requires 2.5 hours to perform and is associated with a 15% to 20% risk of postoperative pudendal neuralgia. It is currently recommended for severe cases of vestibulitis; for cyst formation post simple vestibulectomy; and for failure of the simple vestibulectomy operation.

Success rates for the above procedures vis-à-vis elimination of entry pain associated with intercourse is greater than 90%. Additionally, the vestibular pain is unlikely to return. Both operations are performed with the patient in the low to medium lithotomy position. The operating microscope is recommended to perform this surgery most effectively.

Simple Vestibulectomy

The initial part of this surgery is identical with the technique used for Bartholin gland excision.

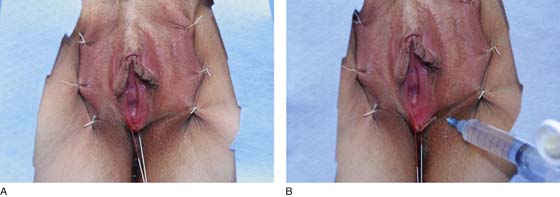

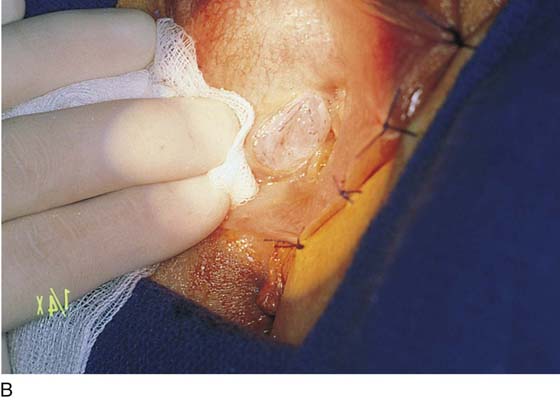

Stay sutures of 0 Vicryl retract the labia to expose the vestibule, and a 1 : 100 solution of vasopressin is injected via a 25-gauge needle into the subdermis of the vestibule (Fig. 67–4A, B).

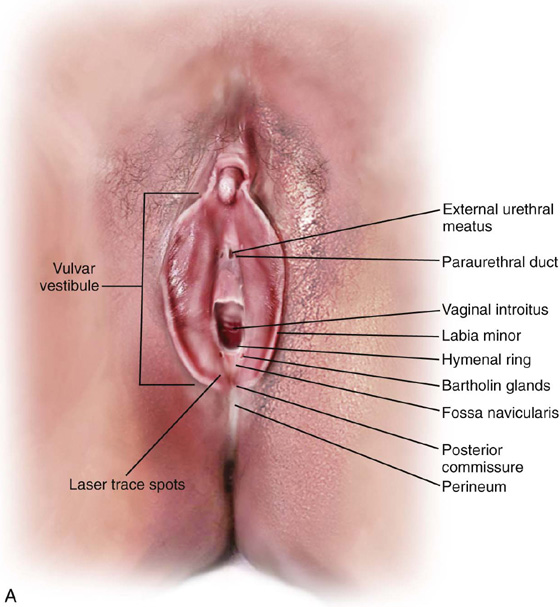

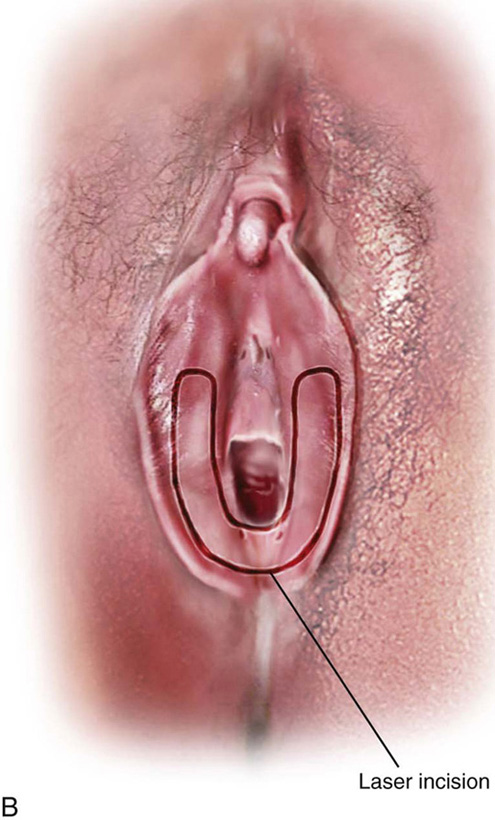

A carbon dioxide (CO2) laser is coupled to a microscope via a micromanipulator. The laser control is adjusted to deliver a 1- to 1.5-mm spot at a focal distance of 300 mm. The format is set for a superpulsed beam at 12 W power. The laser beam traces the dimensions of the incision, and the trace spots are then connected by incising the vestibular skin (Fig. 67–5A, B). The initial incision is U-shaped.

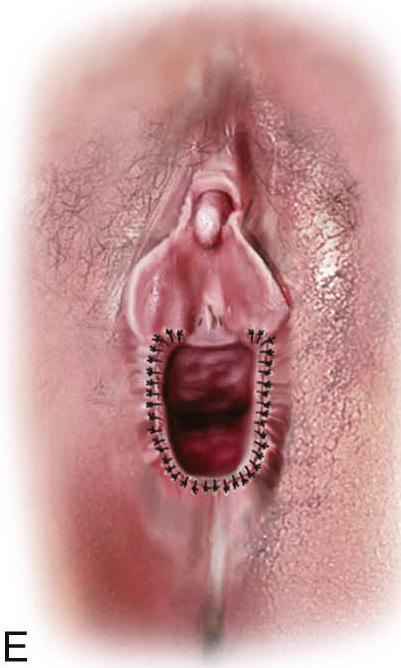

Next, with a Stevens tenotomy, the vestibule with attached Colles’ fascia is sharply excised (Fig. 67–6). Additionally, a 0.5- to 1-cm margin of the lower vagina (which includes the hymenal ring) is removed. Hemostasis and wound approximation are obtained by placing a series of pleating fascial stitches of 3-0 Vicryl (Fig. 67–7A). Next, the skin is closed with interrupted 3-0 Vicryl stitches. Cosmetically, the operative result is quite good. At the same time, the vaginal inlet has been reshaped and widened to permit two fingerwidths (2.5 to 4 cm) for easy coital entry (Fig. 67–7B).

Vestibulectomy With Radical Bartholin Gland Excision

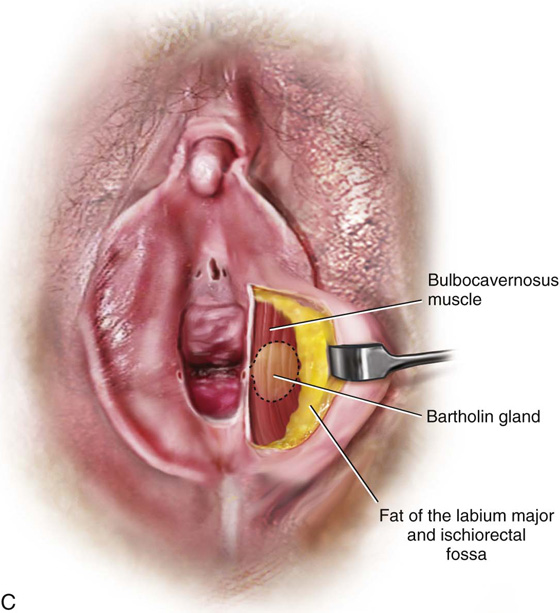

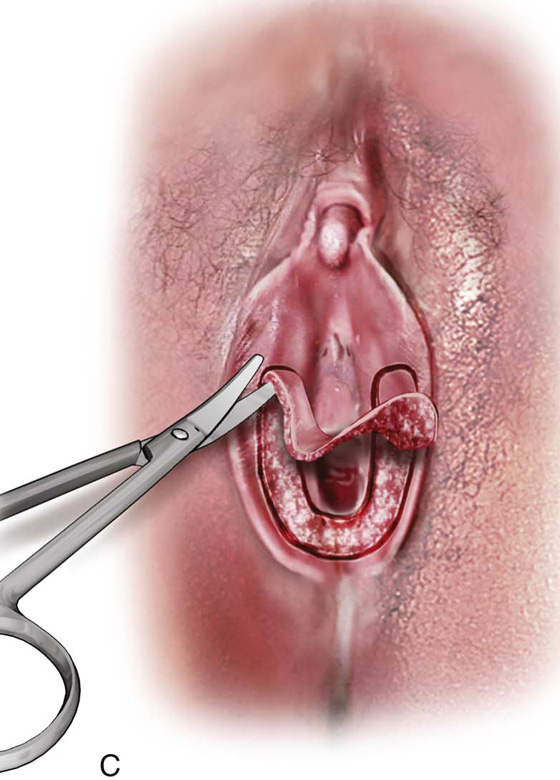

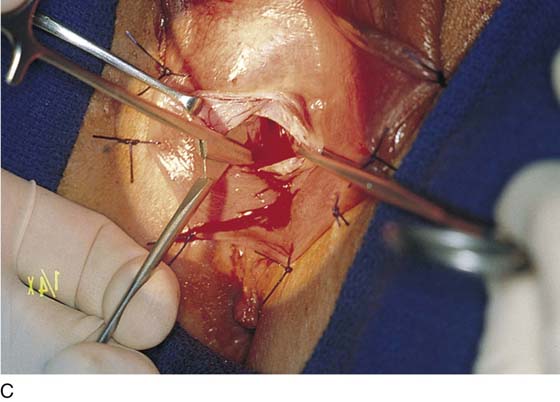

This operation is more complex. It begins with the same trace incision described for simple vestibulectomy (Fig. 67–8A, B). A mosquito clamp is then inserted parallel to and along the outer wall of the vagina to develop a space 2 cm deep from the introital surface (Fig. 67–8C).

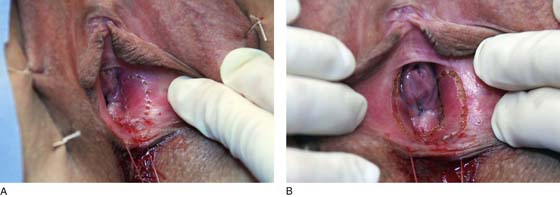

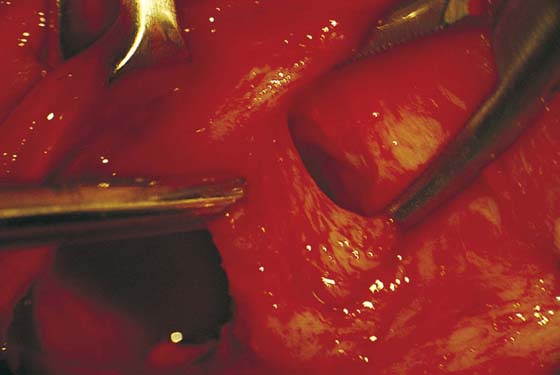

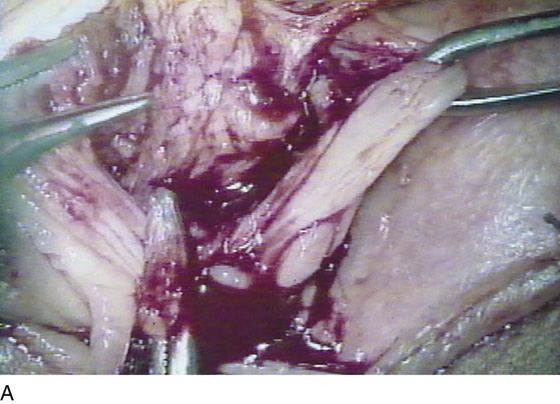

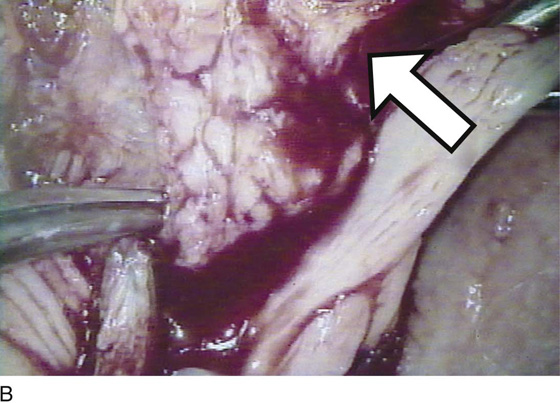

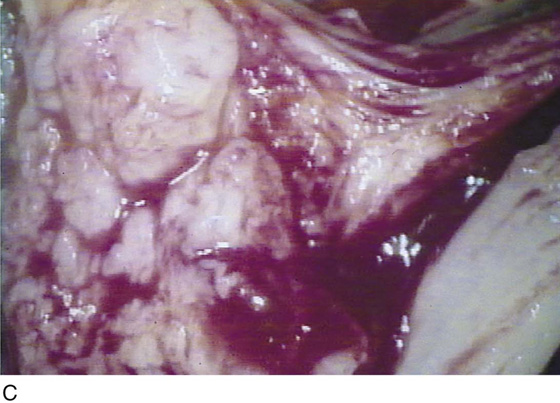

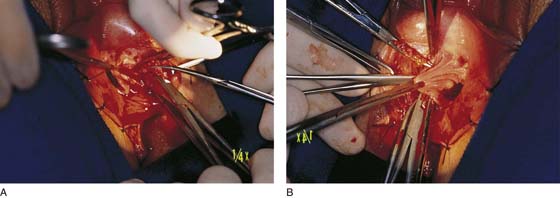

Next, the mosquito clamp is moved 1 to 1.5 cm laterally to develop a similar space into the fat of the ischiorectal fossa (Fig. 67–8D). The two spaces differ significantly. The medical space is dominated above (superiorly) by the vestibular bulb and the vaginal wall sinuses. The lateral space contains a few small arteries and veins, but principally fatty tissue. At this point, the bulbocavernosus muscle is identified (Fig. 67–9). Immediately below the muscle is the Bartholin gland (Fig. 67–10). Under magnification, the lobules and the texture of the gland can be identified as distinct from surrounding muscle, fat, and connective tissue (Fig. 67–10B, C). The gland is isolated anteriorly and posteriorly by the application of mosquito clamps (Fig. 67–11). The gland is excised and all pedicle sutures ligated with 4-0 Vicryl. All vessels are suture-ligated, and the field is secured from bleeding and irrigated (Fig. 67–12A, B). The fossa previously occupied by the gland measures approximately 1 to 1.5 cm from the surface of the vestibule. The dead space is closed with interrupted 3-0 Vicryl sutures. A doubly gloved finger is placed in the anus to verify its location relative to the operative field, as well as its integrity. Next, the vestibular skin is cut away (Fig. 67–13A through C). The vagina is advanced to cover the defect and is closed transversely to the surrounding perineal skin (Fig. 67–14). The overall effect is to actually enlarge the vaginal opening.

FIGURE 67–1 A. This drawing illustrates the topographic anatomy of the vestibule and Bartholin glands/ducts. It also shows the relationship of the paraurethral ducts to the ureter. Noteworthy is the relationship of the anus to the posterior aspect of the vestibule and lower vagina. B. A deep dissection of the vestibule (left) and a superficial dissection (right) are shown here. The bulbocavernosus muscle has been removed on the left side. The arterial blood supply emanates from the internal pudendal artery. The vessel enters the perineum with the pudendal artery. The vessel enters the perineum with the pudendal nerve medial to the ischial tuberosity (i.e., from a posterolateral direction). C. The bulbocavernosus muscle overlies the Bartholin gland; lateral to the gland is the fat of the labium majus and ischiorectal fossa.

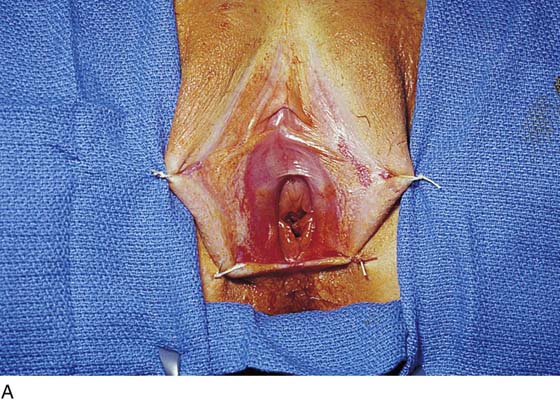

FIGURE 67–2 Preoperative view of the vestibule in a woman afflicted with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. Note the erythema around the Bartholin ducts, as well as the vascular ectasia (punctation).

FIGURE 67–3 A through E. The technique of simple vestibulectomy is illustrated here. A. Initially, carbon dioxide (CO2) laser spots trace the boundaries of the U-shaped incision. B. Via a tightly focused laser beam, the dots are connected and a deeper incision is completed (C) with Stevens scissors. The skin and a thickness of Colles’ fascia are removed, and the specimen sent to pathology. D. Hemostasis and wound apposition are accomplished with fascial pleating stitches. E. Finally, the skin is closed with interrupted sutures. The vagina has been advanced, and the introitus has been widened.

FIGURE 67–4 A. Exposure to the vestibule is provided by suturing back the labia majora. The suture at the fossa navicularis is not tied but is pulled caudad for traction. B. A 1 : 100 dilution of vasopressin is injected subdermally to provide hemostasis, as well as a heat sink to absorb the carbon dioxide (CO2) laser beam.

FIGURE 67–5 A. Trace spots are placed via the attached carbon dioxide (CO2) laser into the vestibule. This outlines where the incision will be placed. B. The trace spots are connected via a deeper incision. Note that the completed incision is U-shaped.

FIGURE 67–6 The vestibule and a 3-mm margin of Colles’ fascia are cut away.

FIGURE 67–7 A. Pleating sutures are placed in Colles’ fascia. This technique pulls the vagina outward toward the distal margin of the incision. B. The skin is closed, advancing the vagina and widening the introitus.

FIGURE 67–8 A. The labia are sutured back for retraction and continuous exposure of the vestibule. B. A 2-cm bloodless incision is made immediately lateral to and above and below the right Bartholin duct opening. C. A mosquito clamp dissects the space between the bulb, the Bartholin gland, and the inner wall of the vagina. Invariably, some bleeding will occur from the bulb. D. A second space is dissected lateral to the gland and the bulb. This space is dissected into the fat of the labium majus and the ischiorectal fossa.

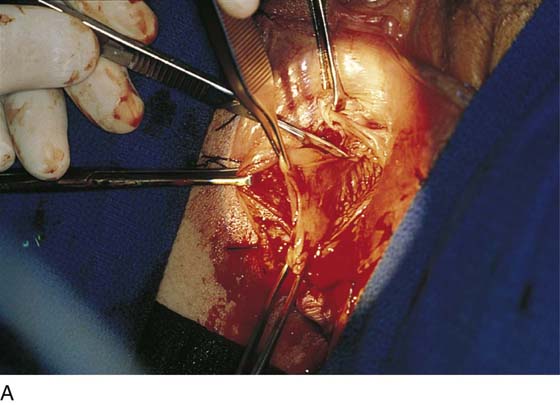

FIGURE 67–9 The edge of the bulbocavernosus muscle is held in the clamps overlying the Bartholin gland.

FIGURE 67–10 A. The lobed Bartholin gland clings to the bulbocavernosus muscle. The scissors point to the gland. B. Higher magnification of part A. The arrow points to the bulbocavernosus muscle. The scissors point to the gland. C. Further magnification of part B. This shows the distinct lobed pattern of the Bartholin gland.

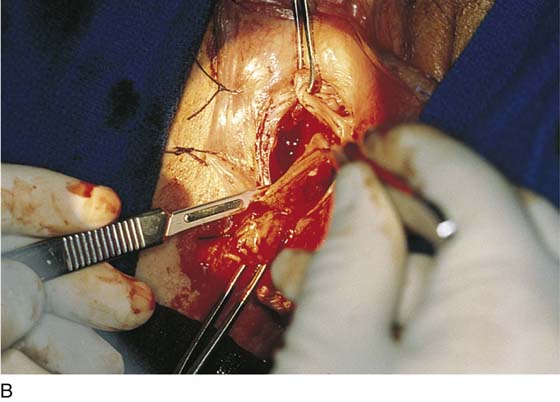

FIGURE 67–11 The gland is isolated between the upper and lower clamps. The lateral edge of the incision is pulled with an Allis clamp to provide exposure. Medially, the vagina is retracted with an Allis clamp.

FIGURE 67–12 A. The Bartholin gland is cut free from the surrounding tissue with Stevens scissors. B. The gland has been excised on the right side. The pedicles will be suture-ligated with 4-0 Vicryl sutures. The right wall of the vagina is pulled caudally with an Allis clamp.

FIGURE 67–13 A. The lower vagina, hymen, and medial aspect of the vestibule are excised with a sharp scalpel. B. The lateral aspect of the vestibule (abutting the labium majus) is excised. C. The excised vestibular tissue is sent to pathology in a separate container from that used for the excised Bartholin gland.

FIGURE 67–14 The wounds have been closed bilaterally and the vagina advanced. The new introitus is enlarged.