Surgery for Pyosalpinx, Tubo-ovarian Abscess, and Pelvic Abscess

Infections emanating from the tube may result in a variety of abscesses that may require surgical intervention. With the exception of a pelvic abscess, which is typically managed by incision and drainage, tubal abscesses are excised if intensive antibiotic treatment fails to elicit a response.

Operative management of these infections utilizes a combination of techniques, including adhesiolysis, salpingectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, and even hysterectomy.

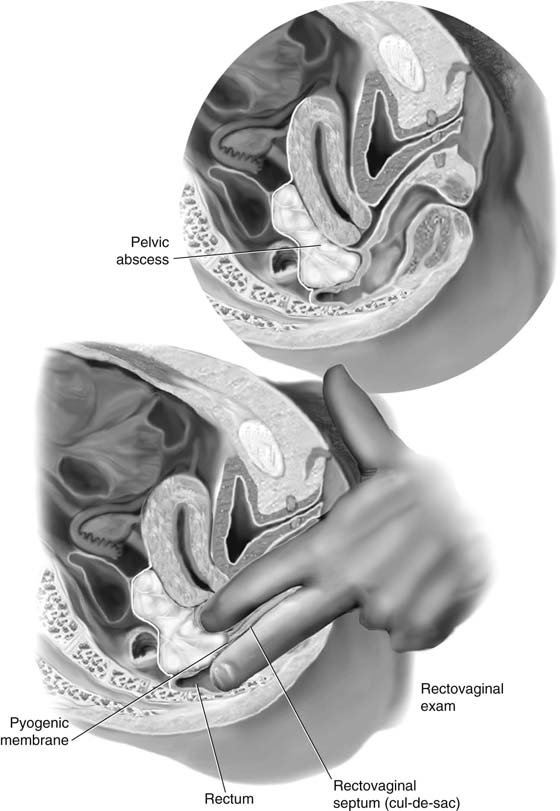

The criteria for drainage of a pelvic abscess are (1) walling-off of the pus (i.e., creation of a pyogenic membrane), and (2) fluctuance (i.e., “pointing” of the abscess just before an anticipated spontaneous rupture). Typically in this location, the pointing process is manifested as the leading edge of the pyogenic membrane dissecting a space within the rectovaginal septum (i.e., between the rectum and vagina). This, of course, is best demonstrated by performance of a rectovaginal examination and palpation of the bulge in the septum.

Drainage is performed transvaginally. The cervix is grasped with a single-toothed tenaculum. The vagina has been carefully and gently prepared with povidone-iodine (Betadine) or another suitable surgical preparatory solution. A weighted or Sims retractor is placed along the posterior vaginal wall.

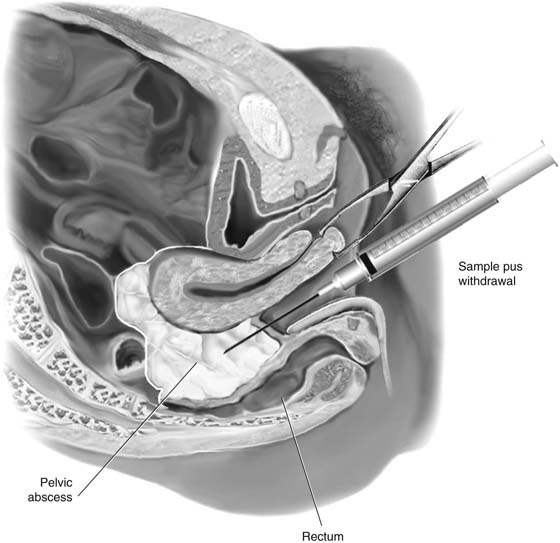

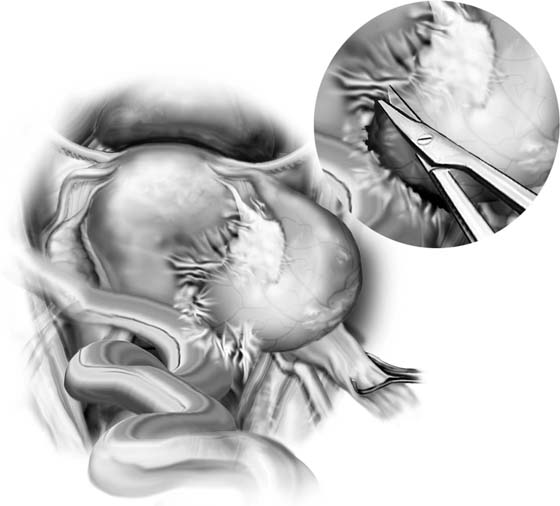

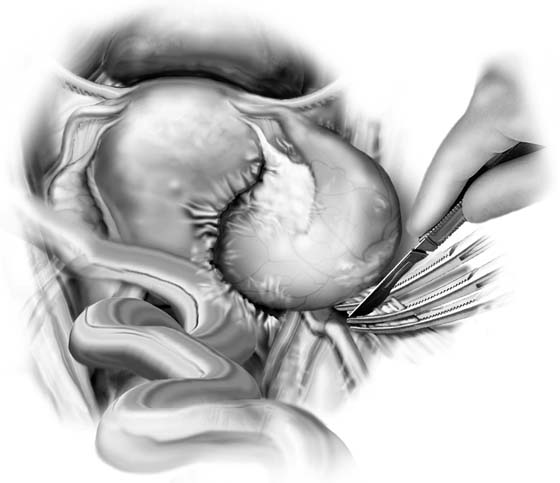

Just before incising into the lower cul-de-sac (septum), the surgeon double-gloves and performs a rectovaginal examination to establish the exact position of the rectum relative to the contemplated incision site (Fig. 23–1). Next, an incision is cut into the cul-de-sac. This may be facilitated by careful insertion of an 18-gauge needle attached to a syringe into the abscess and withdrawal of a sample of pus, followed by cutting directly along the track of the needle with a scalpel (Fig. 23–2).

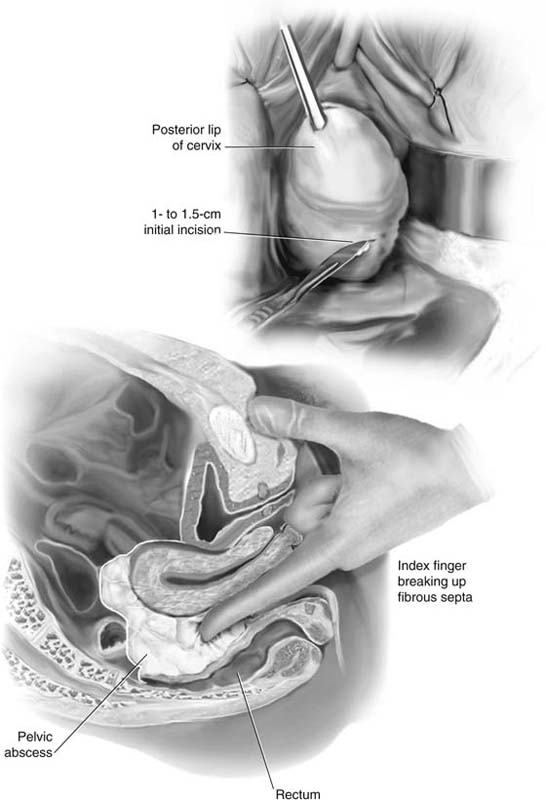

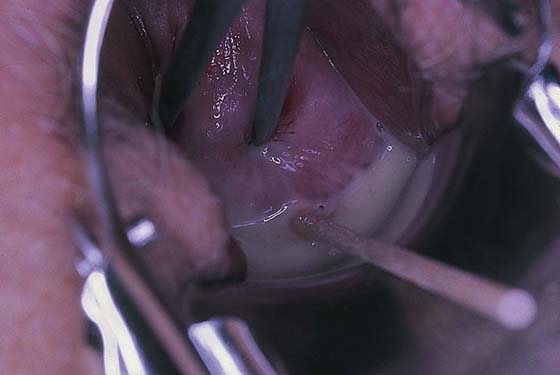

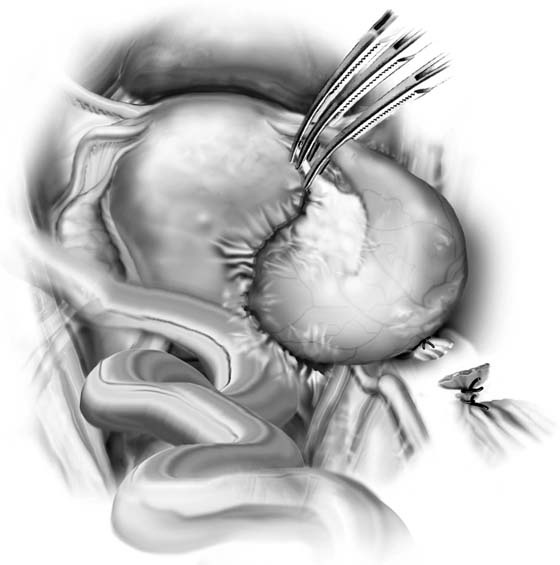

As soon as a 1- to 1.5-cm incision is made, the operator’s index finger is inserted into the abscess cavity to (1) provide a guide for enlarging the incision, and (2) break up fibrous septa to enhance drainage (Fig. 23–3). After appropriate culture samples have been obtained and a large rubber drain or two have been inserted into the abscess cavity, and its edges are sutured to the incision edges with 2-0 chromic catgut, a large safety pin is attached to the exposed end of the drain(s) (Figs. 23–4 and 23–5).

FIGURE 23–1 A pelvic abscess is illustrated via a hemisection through the pelvis. Fluctuance is identified by performing a rectovaginal examination and verifying that the abscess has begun to dissect the rectovaginal septum.

FIGURE 23–2 The posterior lip of the cervix is grasped with a tenaculum. The cervix and the uterus are pulled downward and anteriorly. An 18-gauge needle is inserted into the bulging cul-de-sac mass. The plunger on the syringe is withdrawn and pus is sucked into the syringe.

FIGURE 23–3 With the needle track used as a guide, a scalpel cuts into the abscess cavity. Flow of pus signals entry through the pyogenic membrane. The surgeon’s index finger is inserted into the abscess cavity. Fibrous septa are broken up.

FIGURE 23–4 Pus drained from a pelvic abscess fills the posterior vaginal fornix. A cotton-tipped applicator is inserted into the abscess cavity.

FIGURE 23–5 The initial incision is enlarged to 3 to 4 cm to permit better drainage. A large drain is placed into the abscess cavity and is anchored with two or three 2-0 chromic catgut stitches. It is advised that the total length of the drain be measured and recorded before it is placed, and that the drain length be remeasured and recorded when it is removed. A safety pin should always be inserted into the outside extremity of the drain.

A tubo-ovarian abscess that does not “point” (localize) into the inferior portion of the pelvis but instead enlarges into the upper abdomen may rupture intraperitoneally. This results in spreading of peritonitis from the lower abdomen and pelvis into the upper abdomen, creating an emergency situation. An enlarging tubo-ovarian abscess is a hazard for rupture because the ovary, in contrast to the oviduct, does not have the capacity to expand when pus collects within its substance. Hence, an enlarging tubo-ovarian mass is unpredictable and should be excised (Fig. 23–6).

The tube is grasped at its distal extreme with a Babcock clamp. The infundibulopelvic ligament is grasped with a Babcock clamp, and a traction suture of 0 or 1-0 Vicryl is placed through the utero-ovarian ligament. Dissection is carried upward and retroperitoneally to separate the ovarian vessels from the ureter above the point where the two structures cross into the pelvis over the common iliac artery (Fig. 23–7). The infundibulopelvic ligament is triply clamped and sectioned. The dissection is carried inferiorly to facilitate separation of the tubo-ovarian complex from surrounding structures. The mass is invariably stuck to the intestine, which must be sharply separated from the abscess (Fig. 23–8).

Next, the distal tube and the utero-ovarian ligament are together triply clamped (Fig. 23–9). The tubo-ovarian abscess now is isolated and can be excised (Fig. 23–10A, B). Hemostasis is secured by doubly suture-ligating beneath the two clamps left on the infundibulopelvic and utero-ovarian pedicles.

The ureter, small and large intestines, and opposite adnexa are carefully examined for any disease or injury. Vascular pedicles are rechecked for bleeding (Fig. 23–11). Copious irrigation is performed. Drains are inserted into the cul-de-sac and lateral gutter. These are brought out of the abdomen through separate stab wounds.

FIGURE 23–6 The right adnexa is involved in a common infectious mass: a tubo-ovarian abscess.

FIGURE 23–7 The infundibulopelvic ligament is grasped with a Babcock clamp for traction. The utero-ovarian ligament, if visible, likewise may be grasped for traction. Adhesions between the mass and neighboring structures (in this figure, intestine) are sharply divided.

FIGURE 23–8 The infundibulopelvic ligament is secured from its close neighbor, the ureter. The ligament containing the ovarian vessels is triply clamped, divided, and doubly suture-ligated with 0 Vicryl.

FIGURE 23–9 The oviduct and the utero-ovarian ligament are likewise triply clamped, cut, and doubly suture-ligated.

FIGURE 23–10 A. The large, pus-filled mass is excised en masse. The mass should be cut open while fresh, and a variety of cultures obtained. The specimens should be immediately sent to bacteriology. B. On occasion, a hysterectomy may be performed together with the salpingo-oophorectomy. Depending on the patient’s clinical condition, this may be a total or a subtotal hysterectomy.

FIGURE 23–11 After the diseased adnexa have been excised, the ureter is carefully inspected for its integrity before the peritoneum is closed. Gutter drains should also be placed before closure.