Surgery for Other Benign Lesions of the Vulva

Inclusion Cyst

An epidermal inclusion cyst is another name for a sebaceous cyst. They are common wherever hair and sebaceous glands are present (Fig. 78–1). They create a swelling and may be painful to the touch. If they become secondarily infected, they will be associated with cellulitis and may form an actual abscess. The cysts form as a result of blockage of the duct exiting the skin surface from the underlying sebaceous gland or hair follicle. When the duct is obstructed, the fatty secretion of the gland and shed-off squamous cells distend the duct and create the cyst (Fig. 78–2).

Initial treatment for an inclusion cyst is the application of hot, wet compresses to the lesion to liquefy the secretion and drain the obstructed duct, with subsequent elimination of the cyst. For recurrent, persistent, or enlarging cysts, the treatment is surgical excision.

For cysts 1 cm or smaller, an elliptical incision is made in the skin encompassing the cyst. The incision is carried deeply to circumscribe the cyst and is wedged inward to meet below the cyst. The entire section, including skin, subcutaneous tissue, cyst wall, and contents, is removed en masse.

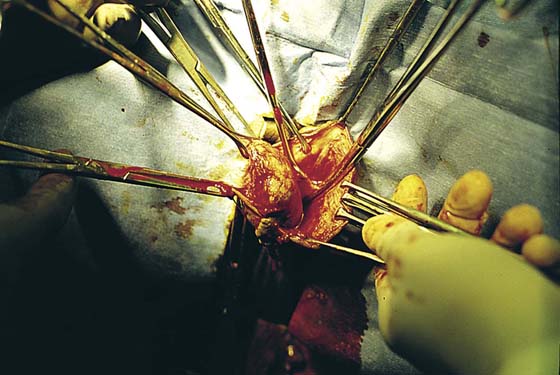

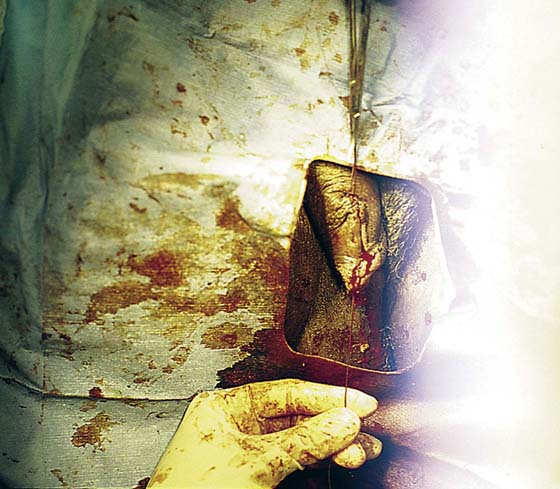

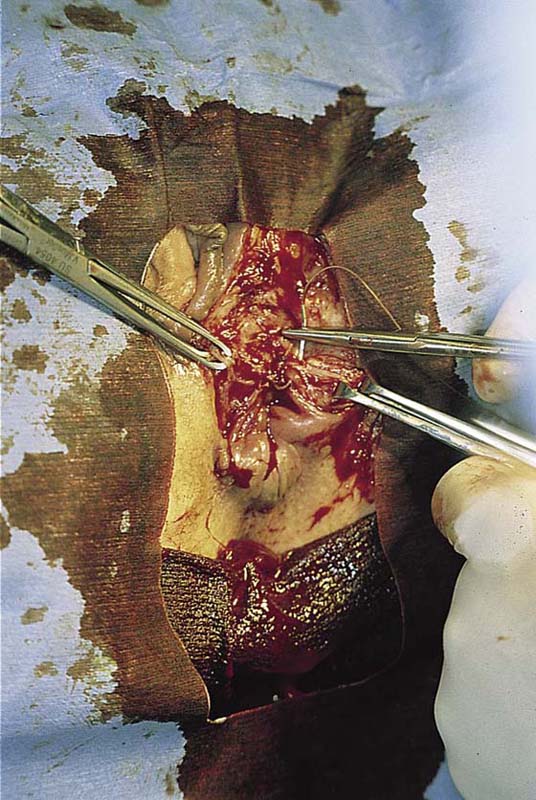

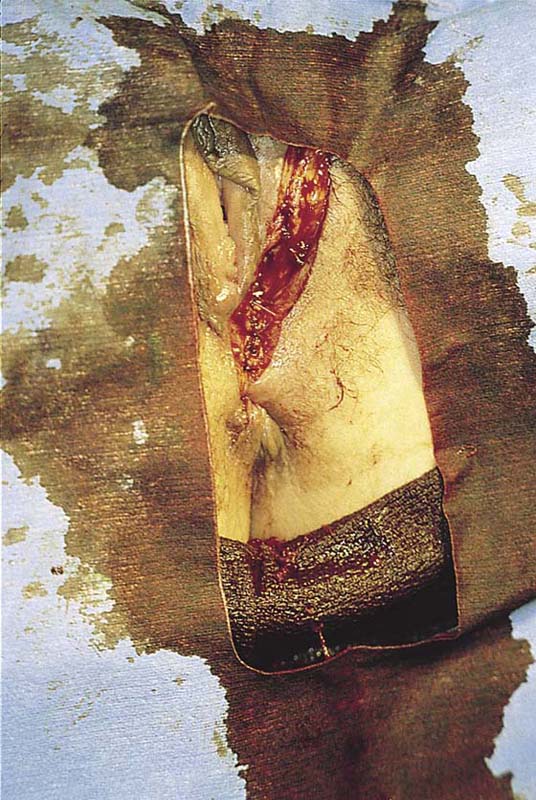

Cysts larger than 1 cm are removed by making a straight-line incision over the mass to the level of the cyst wall beneath the epithelium (Fig. 78–3). The edge of the skin is elevated with Adson-Brown forceps, and the skin margins are dissected away from the cyst wall with Stevens tenotomy scissors. The margins of the skin flaps are then held with Allis clamps for traction, and the cyst wall is completely circumscribed by sharp dissection with the Stevens scissors (Fig. 78–4). The cyst wall should not be grabbed with clamps because this will result in rupture, leakage of contents, and difficulty in extracting the entire cyst (Fig. 78–5). When the entire cyst is freed, it is removed. Excess skin is trimmed, and the wound is closed in layers with 3-0 Vicryl (Fig. 78–6).

FIGURE 78–1 Three sebaceous cysts are seen in the hair-bearing area (right labium majus) of the vulva. These common cysts can be simply excised by making an elliptical incision at the base of the cyst and wedging the incision into the subcutaneous tissue. The wound is closed with two or three interrupted 3-0 Vicryl sutures.

FIGURE 78–2 This large cyst was very painful and was rapidly increasing in size. The differential diagnosis included a cyst of the canal of Nuck with herniated intestine or fat, as well as a large sebaceous (inclusion) cyst.

FIGURE 78–3 An incision is made directly over the mass and is extended to just superior to the mass and to the lower pole of the labium majus.

FIGURE 78–4 With Stevens scissors, the mass is separated from the skin margins and flaps are developed. Allis clamps are applied to the skin margins of the flap for traction. The base of the cyst is separated from the connective tissue. The latter is clamped with tonsil clamps for hemostasis.

FIGURE 78–5 The cyst is completely excised. From the leaking foul-smelling material, it is identified grossly as a sebaceous cyst. The cyst is placed in fixative and sent to pathology.

Hidradenoma

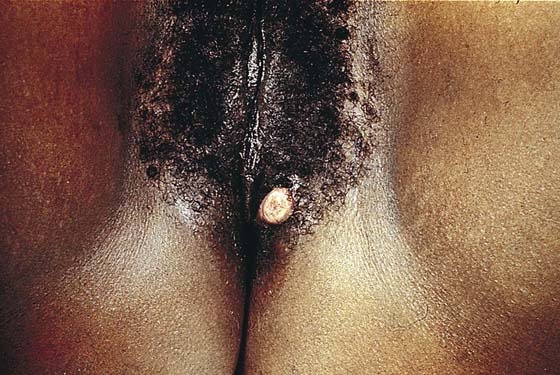

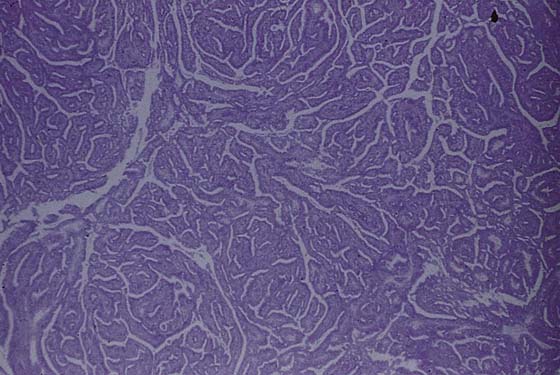

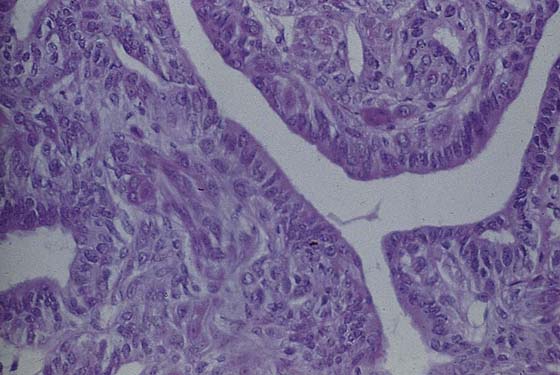

This usually benign sweat gland tumor creates a smooth, elevated, firm nodularity on the vulvar skin surface (Fig. 78–7). It looks like a firm sebaceous cyst. The tumor is small (i.e., <1 cm). The lesion should be excised by circumscribing an ellipse of skin with a margin of 2 to 3 mm around the mass and extending the incision deeper into the subcutaneous tissue. The skin and tumor are grasped with an Allis clamp, and traction is applied with the use of Stevens scissors. The deep subcutaneous fat is dissected free from the base of the tumor, and the entire small mass of tissue containing the lesion is removed. Histopathologically, the appearance of the tumor under the low-power lens of the microscope is ominous because of the glandular complexity (Fig. 78–8). However, higher-power lens inspection reveals the cells and nuclei to be clearly benign (Fig. 78–9).

FIGURE 78–6 The wound is closed in layers with interrupted 3-0 Vicryl sutures.

FIGURE 78–7 The hidradenoma is a solid, raised tumor originating in the sweat glands of the vulva. The lesion is fleshy and well circumscribed. It is also painless. The lesion may be excised in a manner identical to that described for sebaceous cysts.

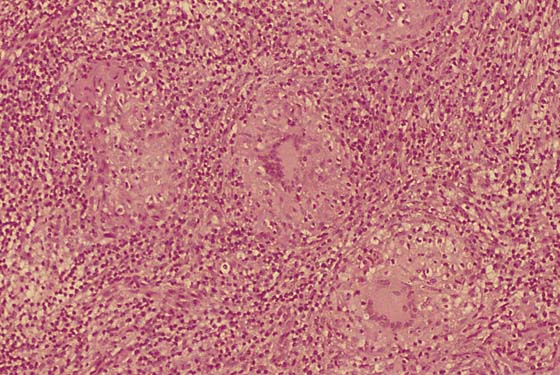

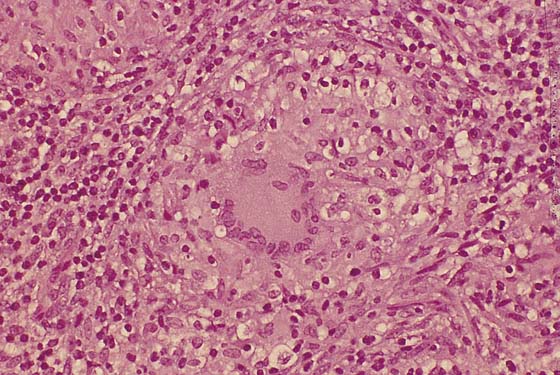

FIGURE 78–8 This low-power microscopic section shows a complex glandular proliferation; it appears to be atypical at least and at worst, malignant.

FIGURE 78–9 High-power microscopic study reveals well-organized glands and normal cytology. The diagnosis is benign hidradenoma.

Labial Fusion

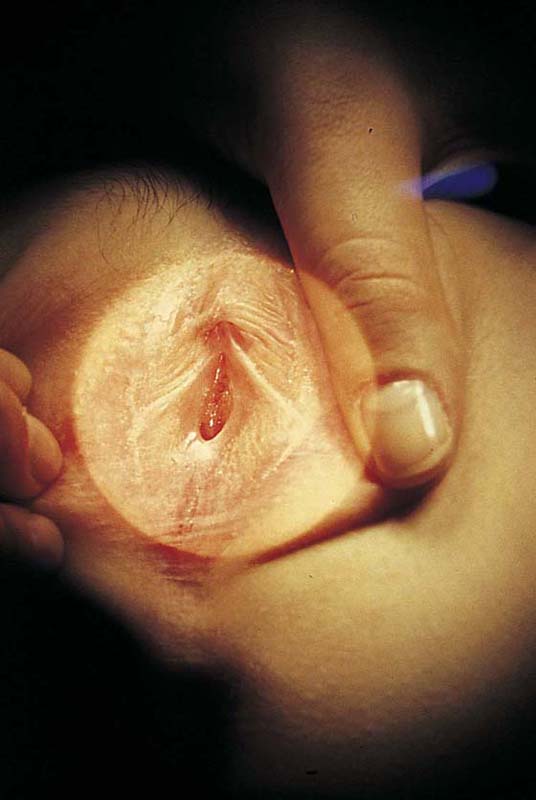

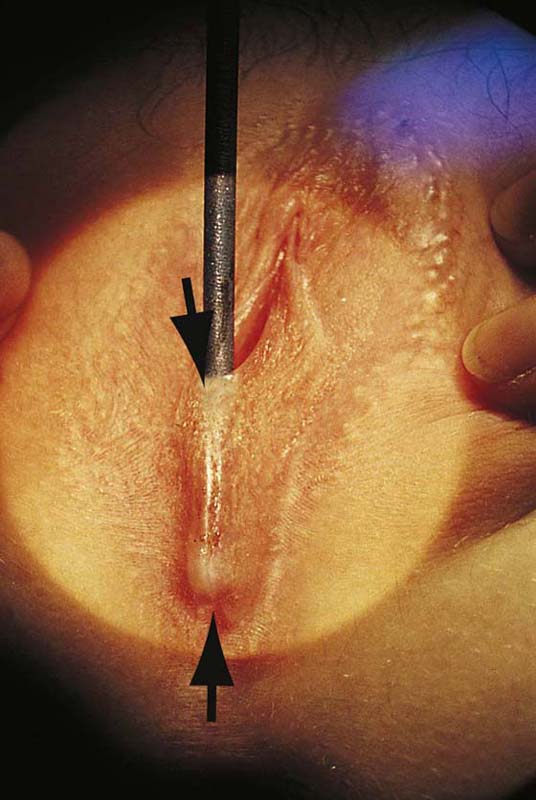

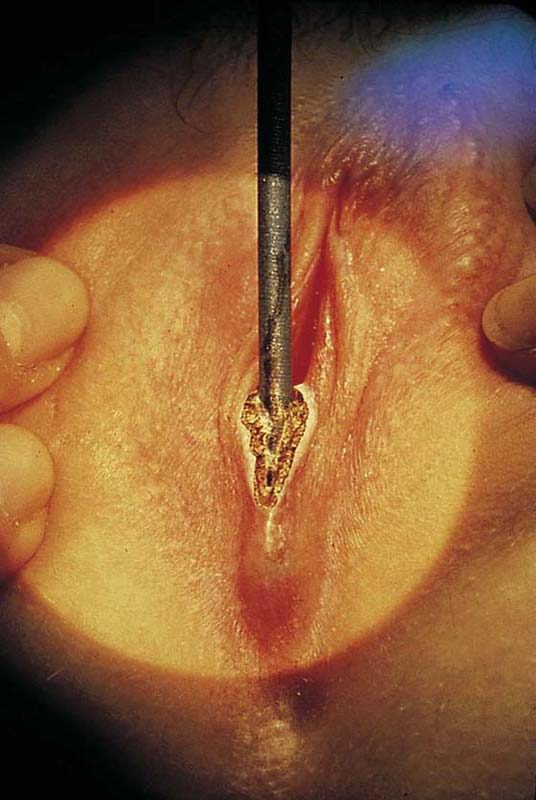

This problem occurs most commonly in the very young (preadolescent girls) (Fig. 78–10) or the elderly. Once firm fusion has occurred, it is unlikely that the application of topical estrogen will relieve the disorder. Surgical separation is usually required. The line of fusion must be accurately identified. This is accomplished with the aid of a magnifying loupe or an operating microscope. A small probe may be placed in the artificial pouch created by the fusion (i.e., the probe is placed behind [deep to] the fused labia). Pressure is exerted outward to stretch the surface of the labia; this in turn helps to identify the points of original fusion. A knife (No. 15 blade) cuts the stretched skin over the probe and down to the probe (Fig. 78–11). After the labia are separated, the edges are closed with a continuous 4-0 polydioxanone (PDS) suture on either side (Fig. 78–12). The suture line is covered with a topical estrogen cream, which is reapplied 2 or 3 times per day during the postoperative and recovery periods.

FIGURE 78–10 This adolescent girl demonstrates fusion of the labia minora.

FIGURE 78–11 A probe has been placed within the pocket created by the fusion. The arrows show the direction of the incision that will be made over the probe (i.e., with the probe used as a backstop).

FIGURE 78–12 An incision is made with a carbon dioxide (CO2) laser; however, the same cut may be made with a scalpel. The edges are closed with a running 4-0 polydioxanone (PDS) suture. The wound is covered with topical estrogen to keep the respective edges from agglutinating.

Draining Vulvar Lesions

Draining vulvar lesions cause a variety of pathologies, including venereal lesions and sinus tracts (Fig. 78–13). Although the first, nonsurgical approach consists of culture of the drainage for a variety of microorganisms (including fungi), diagnosis may be difficult. Drainage points should be explored with the use of lachrymal probes to determine whether a tract exists and where it goes. If a tract is identified, radiologic examination may be helpful in identifying a possible fistula. In this case, the patient should be scheduled for fluoroscopy. A small-gauge vascular catheter is engaged into the sinus opening and is manipulated through the tract. Water-soluble dye is injected during real-time fluoroscopic examination to determine whether a connection with the intestine or another structure exists.

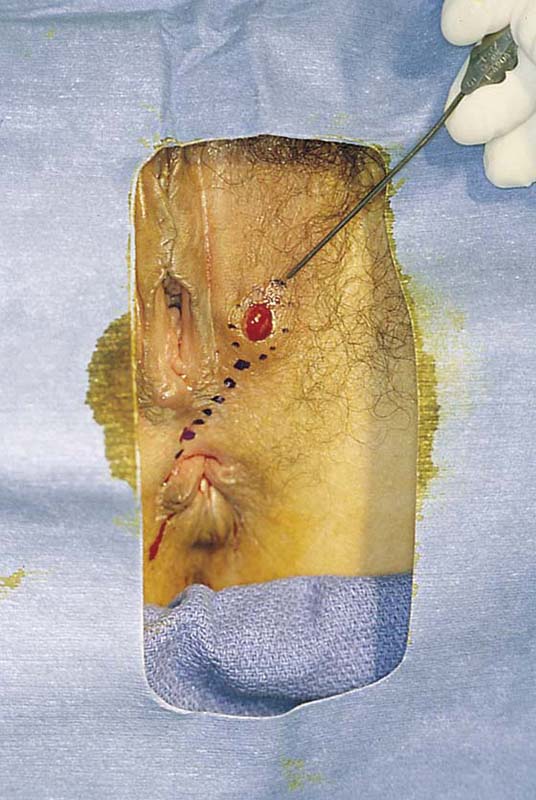

If no fistulous tract is demonstrated and no diagnosis has been made on the culture, then a wide and deep excision of the lesion should be performed (Fig. 78–14). The patient is given a general anesthetic and is placed in the lithotomy position, the skin is prepared, and the operative field is draped. A skin pen is used to mark the boundaries for the excision. The traced area is shallowly circumscribed with a knife (No. 15 scalpel). The cut is extended more deeply into the fat, and the wound edges are grasped with Allis clamps for traction. A wedge-shaped incision is completed on all sides of the lesion margins, and the mass is removed. Tissue samples are placed in sterile containers to be cultured. Special stains are ordered for the pathologic specimen, including Giemsa, silver, acid-fast, and fungal stains. Draining wounds occurring in immigrants from developing countries should carry a high index of suspicion for tuberculosis (Fig. 78–15 through 78–17).

If initial probing reveals a sinus tract to the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., to the anus), then before excision, the patient must undergo a bowel prep (Fig. 78–18). The author recommends the following:

1. Three days before surgery: Begin a low-residue diet.

2. Two days before surgery: Begin a full liquid diet.

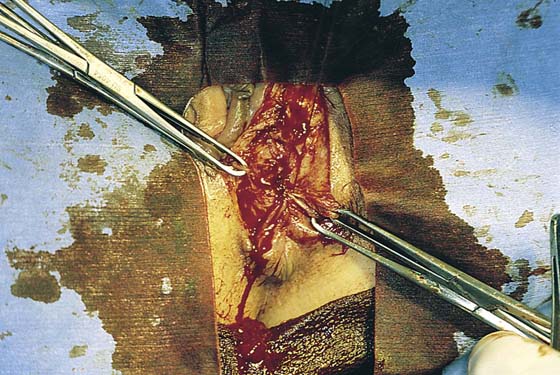

3. The day before surgery: Start a clear liquid diet, and take the following medications: neomycin 1 g by mouth at 11 AM, 12 PM, and 6 PM; metronidazole 500 mg by mouth at 11 AM, 12 PM, and 6 PM; Fleets Phospho-Soda 2.5 oz mixed with 4 oz of clear liquid (7-Up, lemonade, or water), followed by eight glasses of water to be completed by 1 PM; and metoclopramide (Reglan) 10 mg, one by mouth every 6 hours starting at 8 AM on the day before surgery (total, four tablets). The patient is anesthetized and is placed in the dorsal lithotomy position, and the skin and vagina are prepared. The operative site is draped. A probe is placed in the sinus tract, and the path of the tract is traced on the skin surface with a marking pen (Fig. 78–19). An incision is made on either side of the tract with a 5-mm margin on either side of the trace line. This cut is carried down deep to the palpable probe and is wedged inward below the tract. The entire sinus tract is excised (Fig. 78–20). The anal sphincter margins are grasped with Allis clamps. The anal mucosa is repaired with interrupted 2-0 chromic catgut sutures (Fig. 78–21). The sphincter is repaired inferiorly to superiorly with five or six 3-0 Vicryl sutures (Fig. 78–22). A Penrose drain is placed above the sphincter below the fat (i.e., superior to Colles’ fascia). The fat is closed with interrupted 3-0 Vicryl sutures (Fig. 78–23). The skin is finally approximated with 3-0 Vicryl sutures. A large safety pin is placed into the terminal portion of the Penrose drain, and the edges of the drain are anchored to the skin with 3-0 chromic catgut sutures (Fig. 78–24). The wound is covered with silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene) cream, which the patient will apply 3 times daily and at bedtime during the postoperative recovery period. Crohn’s disease may present with cutaneous vulvar fistulas. In this case, there may be multiple tracts, and wound breakdown is a significant risk. Consultation with the gastroenterologist should be carried out preoperatively and a therapeutic program instituted postoperatively if, in fact, the surgery proceeds at all.

Vulvar Hemangiomas and Varicosities

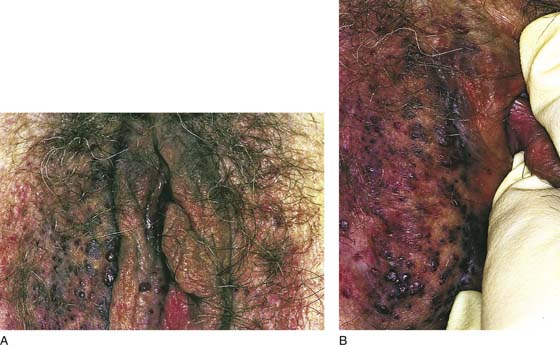

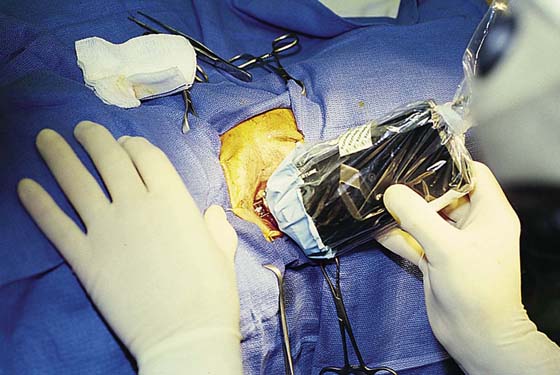

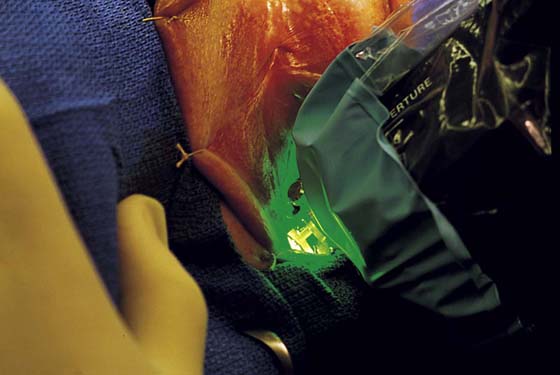

Congenital hemangiomas and acquired varicosities may be troubling to patients not only because of their unsightly appearance but also because of their tendency to bleed as a result of even slight trauma (Fig. 78–25). The preferred treatment for these lesions is phototherapy with a selected-wavelength laser (Fig. 78–26A, B). The KTP laser coupled to a computer-controlled scanner is ideal for this type of surgery because the wavelength of this laser (532 nm) is very close to that of the light absorption of hemoglobin (Fig. 78–27). Similarly, the argon laser fits into this category. The scanner automatically exposes the laser energy (4 W) to the skin for a short time (30 to 60 msec) in several hundred pulses (Fig. 78–28). Thus, minimal surface skin effects are noted. In fact, the light skin of a white patient actually reflects away the laser energy. Because the selected absorption band corresponds to that of hemoglobin, the dilated vessels absorb the laser light selectively and undergo coagulation as well as slow obliteration. The end result consists of removal of the offending blood vessels and a nice cosmetic result with minimal discomfort, immediate recovery, low risk, and short hospitalization (Fig. 78–29). All cases may be performed with systemic analgesia and injection of local anesthesia. Postoperatively, the patient should cover the vulva with Silvadene or another suitable topical cream to keep the skin protected and moist. Treatments may be staged (i.e., three or four treatments over a period of months). The preferred interval between laser treatments is 1 month.

FIGURE 78–13 This woman from Ethiopia presented with a fungating, draining lesion of the perineum. All cultures were negative.

FIGURE 78–14 A deep wedge biopsy excised the skin lesion and extended into the underlying fat. A fistulous tract was probed 8 cm deep, paralleling the colon. Fluoroscopic dye studies with the tract cannulated revealed no connection with the large or small intestine.

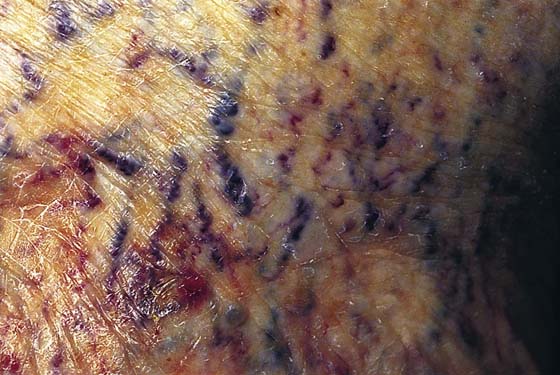

FIGURE 78–15 The tuberculin skin test created 2 cm of induration and eventually ulcerated.

FIGURE 78–16 Microscopic sections from the deep wedge excisional biopsy showed granulomas and Langerhans giant cells.

FIGURE 78–17 High-power view of the giant cell within a granuloma. Note the peripheral arrangement of the nuclei. The patient was treated with antituberculosis medications.

FIGURE 78–18 The vulvar draining sinus was probed toward the anus. The marking pen dots indicate the direction of the sinus tract.

FIGURE 78–19 The lacrimal probe has been engaged in the granulating sinus opening on the labium majus. The probe extends into the anus.

FIGURE 78–20 The initial incision is made over the probe. The dissection continues through the external sphincter into the anus. The entire sinus tract is excised. The margins of the anus are held in the Allis clamps. Countertraction is produced by a single Allis clamp located at the vulvar skin margin.

FIGURE 78–21 The anal mucosa is repaired with interrupted 2-0 or 3-0 chromic catgut sutures.

FIGURE 78–22 The anal sphincter is repaired with 3-0 Vicryl sutures placed from the lowermost portion to the uppermost extreme of the sphincter.

FIGURE 78–23 The subcutaneous tissue is approximated with 3-0 Vicryl sutures.

FIGURE 78–24 A drain is placed above the sphincter repair below the fat but above Colles’ fascial layer. The edges of the drain are sutured to the skin edges with two 3-0 catgut sutures. Note the large safety pin placed through the Penrose drain.

FIGURE 78–25 Magnified view of vulvar skin demonstrating extensive varicosities. These lesions were acquired as a result of multiple childbearing episodes and a familial disposition to form varicosities.

FIGURE 78–26 A. This young woman was afflicted with a congenital vulvar angioma affecting the labia minora and majora and the vestibule. The thin-walled vessels frequently burst, resulting in heavy vulvar bleeding. B. The labia majora were particularly affected. Note the grapelike cluster of vessels in the upper part of the picture.

FIGURE 78–27 The KTP-532 laser is connected to a computerized scanner. The handpiece controls the shutter. Attached to the end of this handpiece is a sterile quartz lens, which is pressed against the skin. The laser is set to deliver multiple pulses of 40- to 60-msec duration. The quartz lens is moved progressively over the field. In this case, the patient was staged for three treatment periods under local anesthesia.

FIGURE 78–28 The KTP-532 laser Hexascan photocoagulation system delivers intense pure green light to the angioma. The wavelength corresponds to the absorption spectrum of hemoglobin. The blood therefore selectively absorbs the laser light, whereas the surrounding skin reflects it.

FIGURE 78–29 In a comparison of this post-treatment photograph with Figure 78-26 (pretreatment), the vessels are shown to have been virtually erased with no skin damage and no scarring. Note the hair growth.

Lymphangioma

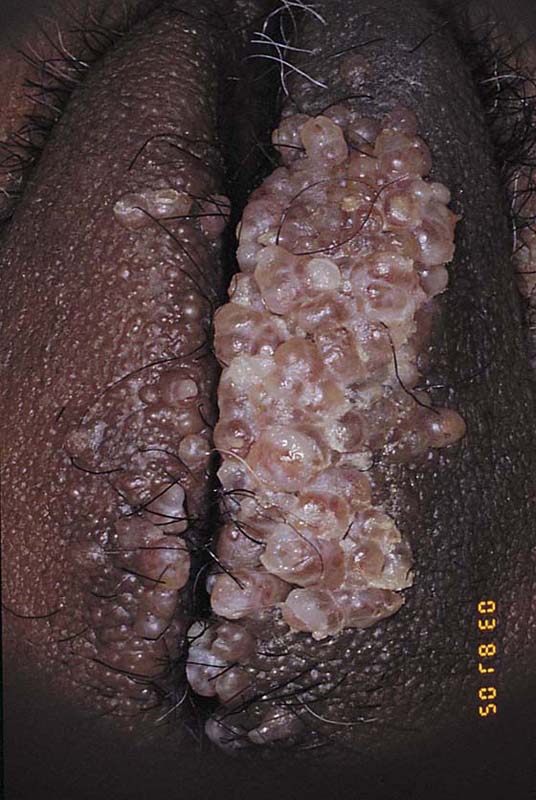

Lymphangioma usually presents as a unilateral diffuse swelling of one labium majus (Fig. 78–30). The skin of the labium contains numerous bleblike surface lesions that are actually dilated subdermal lymphatics (Fig. 78–31). These are not infrequently misdiagnosed as condylomata acuminata. The lymphangioma causes a drawing type of discomfort and is clearly unsightly for the patient. The treatment for this disorder is excision of the labium majus. The patient is placed in the lithotomy position, prepared, and draped. The labial margins are outlined with a marking pen. The skin margins are cut and extended down to the level of Colles’ fascia. The labium is placed on sharp traction by applying Allis clamps to the dorsum of the labium. Branches of the internal pudendal artery are clamped and suture-ligated with 3-0 or 4-0 Vicryl. After the labium has been removed and hemostasis attained, the wound is closed in layers with 3-0 Vicryl. The skin is approximated with interrupted 3-0 Vicryl with sutures or a subcuticular continuous suture (Figs. 78–32 and 78–33). Excellent healing with minimal deformity can be anticipated (Figs. 78–34 and 78–35).

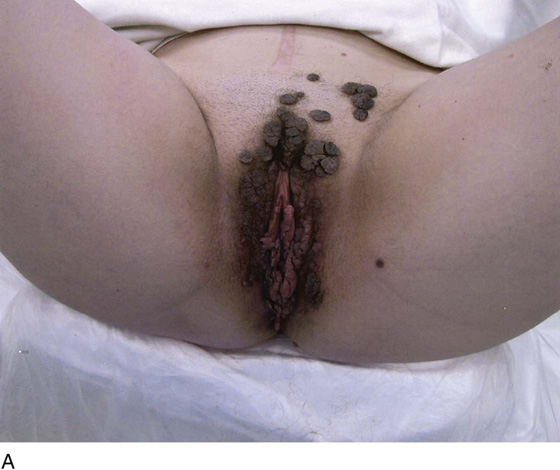

Condyloma Acuminata

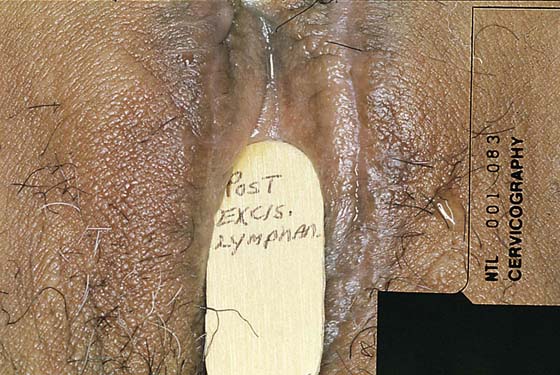

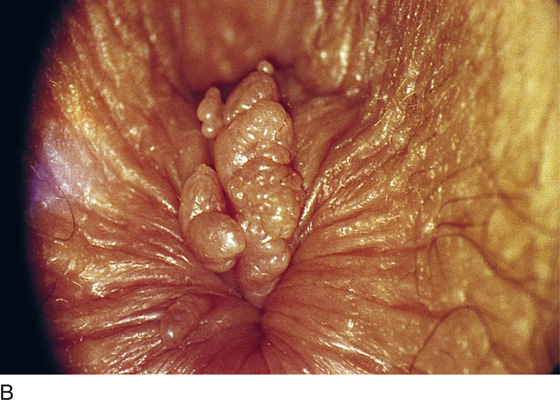

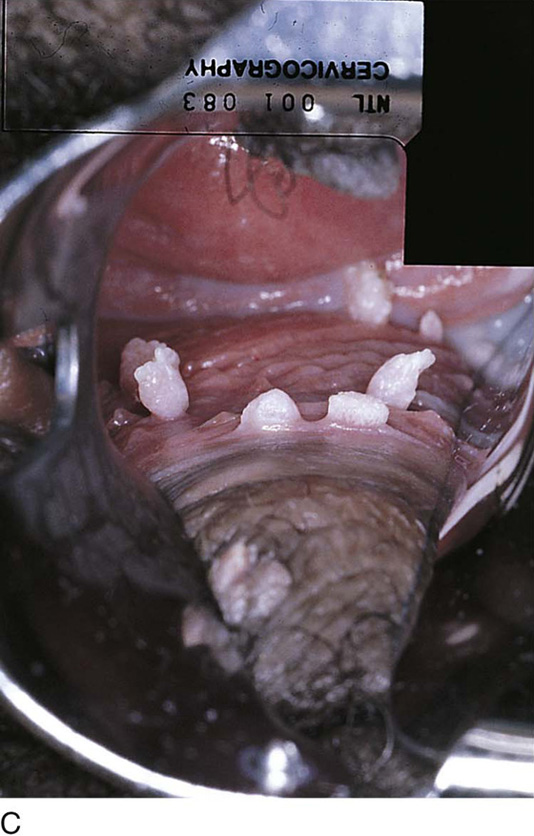

This is a very common viral venereal infection. Venereal warts are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), types 6 and 11. Although these viral types have low malignant potential, several warts should be sampled and sent for pathologic evaluation before any surgical treatment is undertaken. Conservative topical treatment should be attempted for mild infections before surgical removal is considered. If these simple, conservative measures fail, then surgery under general anesthesia is indicated. Severe, widespread warts are unlikely to respond to simple measures (Fig. 78–36). Likewise, treatment with interferon has a poor response rate for numerous and widespread genital warts. Direct injection of warts with interferon is satisfactory for minimal disease but impractical and expensive for moderate or severe disease. A serum chorionic gonadotropin test should be performed to determine that pregnancy does not exist. Other venereal infections (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia) should be tested for (Figs. 78–37 and 78–38). If any of the aforementioned disorders is diagnosed, it should be treated. Preoperatively, condylomata lata or vulvar carcinoma in situ at first glance may be confused with condylomata acuminata. The surgeon also should take suitable precautions during surgery to protect himself or herself from contamination via vapor, blood, or body fluids. The treatment of choice for significant condylomata acuminata infestation is carbon dioxide (CO2) laser vaporization followed by 3 to 6 months of systemic interferon-alfa injections. One million units of interferon is administered subcutaneously (self-injection) 3 times per week (Fig. 78–39). The patient is given a general anesthetic, placed in the lithotomy position, prepared, and draped (Fig. 78–40A, B). The CO2 laser is coupled to an operating microscope and controlled by a micromanipulator. Power is set according to the skill and experience of the operator to a range of 20 to 60 W. A 2- to 3-mm spot diameter is set by first firing the laser into a wooden tongue depressor. The microscope objective lens is coupled to the laser lens at a 300-mm focal distance. Power is initially reduced to 20 W (i.e., power density of 500 W/cm2), and a trace incision is made to encompass the field of vaporization. All warts and surrounding skin are then vaporized to a level no deeper than the surrounding normal skin surface (Fig. 78–40C, D). A 2- to 3-mm margin is “brushed” by reducing laser power to 5 to 10 W to simply blanch (lightly coagulate) the surrounding epithelium (Fig. 78–41). A laser speculum (with attached smoke evacuator) examination is carried out to detect and eliminate vaginal and cervical warts by spot vaporization (Fig. 78–42A). A narrow laser speculum is inserted into the anus to expose anal warts (Fig. 78–42B). These likewise are vaporized at 20 W of power (Fig. 78–42C). When the vaporization is complete, all char is washed away with sterile water, and the wound is covered with Silvadene cream (Fig. 78–43). Other skin lesions elsewhere on the body are carefully evaluated (Fig. 78–44). Postoperatively, the patient is instructed to soak in salt water (Instant Ocean) tub baths 3 times per day and to apply Silvadene cream liberally to the wound 3 times per day, as well as at bedtime (Fig. 78–45). The patient is examined frequently to ensure that the wound is clean and healing appropriately. Clindamycin (Cleocin) cream is applied twice daily into the vagina if that area has been involved (Fig. 78–46). In limited circumstances, urethane dressings may be applied to enhance healing and diminish postoperative pain (Fig. 78–47).

FIGURE 78–30 This Indian woman complained of “warts” on her genitalia. It is obvious that the lesions on the left labium majus are not warts but rather a type of angioma.

FIGURE 78–31 Close colposcopic evaluation under magnification reveals the lesion to consist of multiple blebs characteristic of a lymphangioma. The lesion extended deep into the labial fat pad.

FIGURE 78–32 The left labium was excised, and the wound was closed in layers. The skin was approximated with a simple running 3-0 polydioxanone (PDS) suture.

FIGURE 78–33 The healed wound at 6 weeks postoperatively reveals a good cosmetic result.

FIGURE 78–34 This lymphangioma in a white woman had approximately the same distribution as that of the patient in Figure 78-30.

FIGURE 78–35 The postoperative result at 2 months’ post excision is also quite satisfactory. Wide and deep excision to ensure clear margins will completely eradicate the angioma.

FIGURE 78–36 Severe, widespread genital warts (condylomata acuminata) as shown in this photograph are unlikely to respond to topical treatment regimens.

FIGURE 78–37 This man’s penis is covered with warts. This degree of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection should set off warning signals to the gynecologist. The patient was human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive and died 6 months after carbon dioxide (CO2) laser treatment.

FIGURE 78–38 Although these are warts, their appearance is flatter than that of condylomata acuminata. These are in fact condylomata lata. The serologic test for syphilis was positive, and the biopsy showed that the tissue was teeming with spirochetes.

FIGURE 78–39 Interferon-alfa is indicated for the prevention of recurrent warts. It is initially administered immediately after carbon dioxide (CO2) laser eradication of the condylomata. One million units is injected subcutaneously 3 times per week for 6 months.

FIGURE 78–40 A. This insulin-dependent diabetic patient has extensive warts. Topical treatments have failed. B. The major distribution of these warts is located in the interlabial sulcus. The warts show typical bilateral involvement. C. Carbon dioxide (CO2) laser ablation is performed with the patient under general anesthesia. The warts are carefully vaporized to the level of the surrounding skin surface and no deeper. D. The warts were vaporized with an UltraPulse CO2 laser coupled to an operating microscope. Note the lack of char and the bright pink appearance of the underlying stroma. This is indicative of minimal heat conduction and likewise normal underlying dermis.

FIGURE 78–41 Another patient has undergone vaporization with a continuous-wave carbon dioxide (CO2) laser. Note the char and stromal heat artifact. The surrounding white area has been brushed. This reduced-power technique only coagulates the surrounding epidermis, which is similar to the effect of laser dermabrasion.

FIGURE 78–42 A. A laser speculum is placed in the vagina. The warts on the left vaginal wall are vaporized. B. Perianal warts are commonly present when a patient has significant vulvar condylomata acuminata. The presence of perianal warts requires inspection of the anus and rectum for warts. C. A thin-bladed speculum has been placed in the rectum. Numerous warts are seen on the intestinal mucosa. These must be vaporized.

FIGURE 78–43 Upon completion of laser vaporization, the wound is covered with Silvadene cream. This treatment is continued until complete healing is observed.

FIGURE 78–44 This forearm lesion in a diabetic woman (see Fig. 78-4A through D) treated for condylomata acuminata represents an area of necrobiosis.

FIGURE 78–45 Every patient who undergoes carbon dioxide (CO2) laser vaporization is instructed to take two or three salt water tub baths per day. Two cups of Instant Ocean are placed in a tub of comfortably warm water. After soaking for 10 minutes, the patient rinses off with fresh water, dries the wound, and applies Silvadene cream liberally over the wound.

FIGURE 78–46 The patient shown in Figure 78-36 underwent extensive laser vaporization. At 2 weeks postoperatively, the vulva is beginning to reepithelialize.

FIGURE 78–47 Alternatively, a urethane dressing (OpSite) may be applied to the treated vulva. This greatly reduces postoperative discomfort.