Surgery for Anal Incontinence

Anatomy of the Rectum and Anal Sphincters

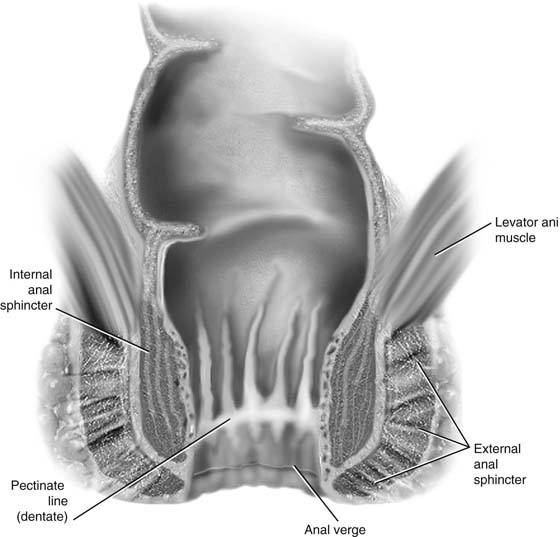

Fecal control is a complex process that involves an intricate interaction between anal function and sensation, rectal compliance, stool consistency, stool volume, colonic transit, and mental alertness. Alteration of any of these can lead to incontinence of gas, liquid, or solid stool. Disruption of the normal anatomy of this area, usually secondary to obstetric trauma, may result in some degree of incontinence. The intact anatomy of the internal anal sphincter, external anal sphincter, and puborectalis division of the levator ani muscle must be understood to fully appreciate anatomic abnormalities that may lead to anal incontinence (Fig. 100–1).

The rectum extends from its junction with the sigmoid colon to the anal orifice. The distribution of smooth muscle is typical for the intestinal tract, with inner circular and outer longitudinal layers of muscle. At the perineal flexure of the rectum, the inner circular layer increases in thickness to form the internal anal sphincter. The internal anal sphincter is under autonomic control (sympathetic and parasympathetic) and is responsible for 85% of resting anal pressure. The outer longitudinal layer of smooth muscle becomes concentrated on the anterior and posterior walls of the rectum, with connections to the perineal body and coccyx, and then passes inferiorly on both sides of the external anal sphincter. The external anal sphincter is composed of striated muscle that is tonically contracted most of the time and can also be voluntarily contracted. The external anal sphincter functions as a unit with the puborectalis portion of the levator ani muscle. The anal sphincter mechanism comprises the internal anal sphincter, the external anal sphincter, and the puborectalis muscle portion of the levator ani (see Fig. 95–1). A spinal reflex causes the striated sphincter to contract during sudden increases in intra-abdominal pressure. The anorectal angle is produced by the anterior pole of the puborectalis muscle. This muscle forms a sling posteriorly around the anorectal junction. The two sphincters are somewhat separated by the conjoint longitudinal layer formed by a merger of the longitudinal layer of the smooth muscle of the rectum and the pubococcygeal fibers of the levator ani muscle. These sphincters encircle the anal canal just distal to the anorectal angle. As was previously mentioned, the internal sphincter is thought to exert most of the resting pressure. The external sphincter, which is innervated by the inferior rectal branch of the pudendal nerve and the perineal branch of the fourth sacral nerve, exerts most of the maximal squeeze pressure. It is felt that a more anatomic repair and perhaps better restoration of a high-pressure zone will result if the repair incorporates both internal and external anal sphincters. These structures are approximately 2 cm thick and 3 to 4 cm long. The actual role of the puborectalis muscle in the incontinence mechanism is somewhat controversial. It has been thought that it supports the rectum above the level of the anorectal angle, keeping the pressure of the enteric contents as well as changes in intra-abdominal pressure away from the sphincteric complex. Recent studies suggest that fecal incontinence is often related to denervation of the pelvic diaphragm and to disruption and denervation of the external anal sphincter.

FIGURE 100–1 Normal anatomy of the distal anal region.

Repair of the Anal Sphincter

When a defect in the sphincteric complex is identified and testing reveals that this is the major factor contributing to the patient’s incontinence of gas, liquid stool, or solid stool, reapproximation of the sphincter should dramatically improve the condition.

Following is a description of an overlapping sphincteroplasty repair for fecal incontinence:

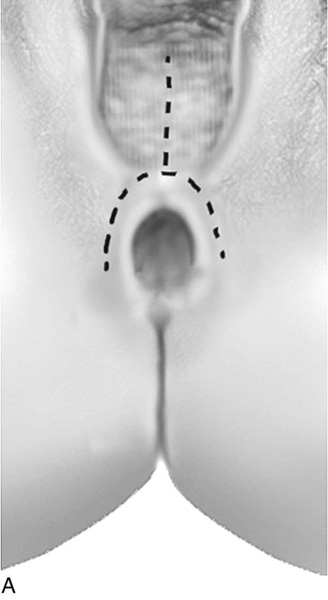

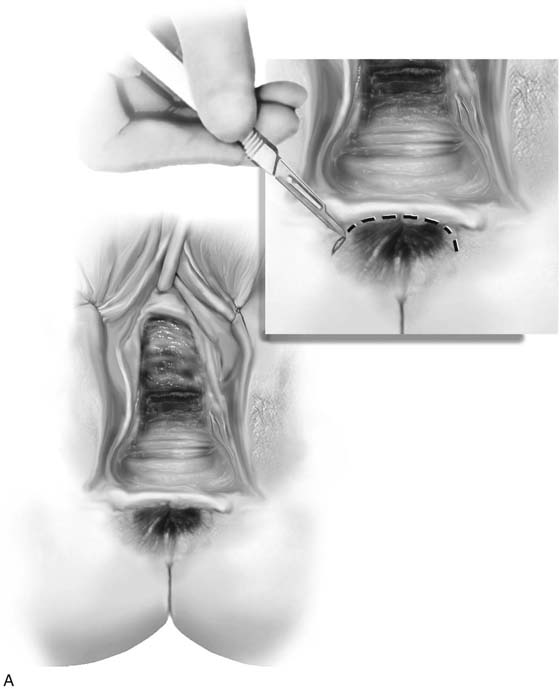

1. The author prefers to perform this repair with a finger in the rectum. An initial inverted-U incision is made above the anal opening from the 9- to the 12- to the 3-o’clock position, followed by a midline incision extending up the remainder of the perineum and into the vagina (Figs. 100–2 through 100–5).

2. The mucosa of the vagina is separated from the anterior wall of the rectum sufficiently laterally and superiorly to provide access to the retracted muscles. Also, the dissection should extend almost to the level of the ischiorectal fossa because most of these patients have a very attenuated perineum, and a perineorrhaphy will need to be performed in conjunction with the anal sphincter repair (see Fig. 100–5).

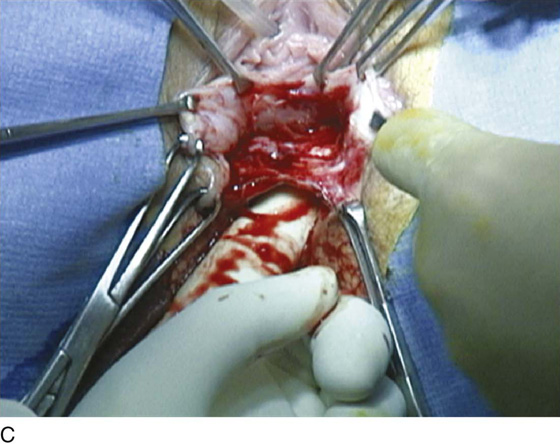

3. Lateral dissection is performed until the ends of the sphincters can be identified. Many times it is helpful to utilize a nerve stimulator or low-power cautery to identify viable muscle, as frequently the viable muscle will be surrounded by scar tissue (Fig. 100–6). The author prefers to divide the scar in the middle, leaving the two ends of the sphincter with the scar attached. It is important to divide the scar but not to trim it from the ends of the sphincter because it will provide tensile strength when the repair is done.

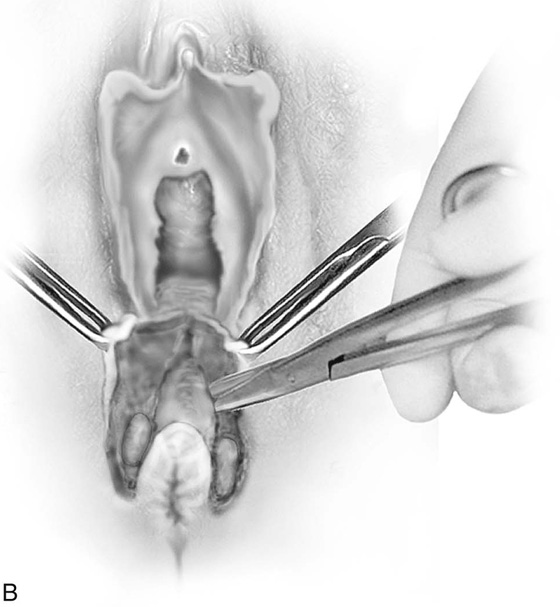

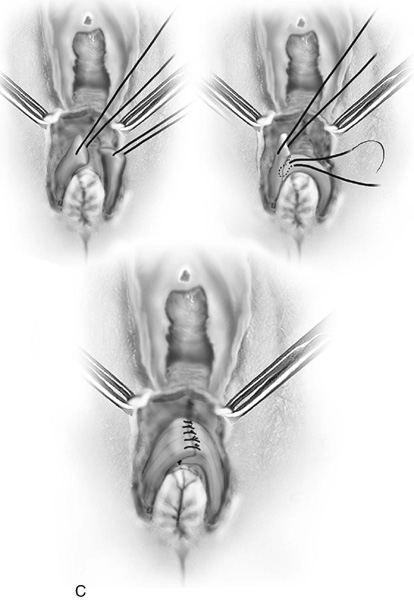

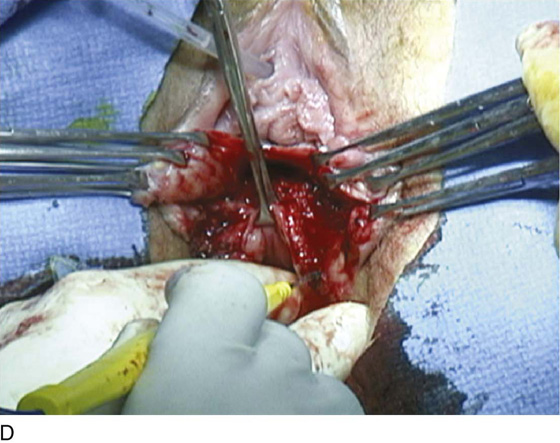

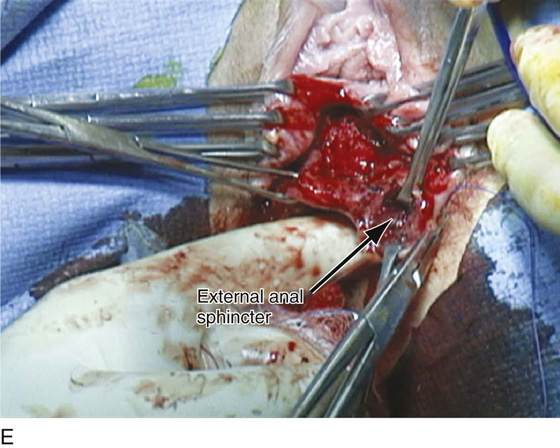

4. The sphincter ends are sufficiently mobilized to allow overlapping of the muscle and are grasped with Allis clamps. If both internal and external muscles are injured, it is preferable to repair them as one unit. This is best performed by incorporating small bites of the anterior wall of the rectum into the sphincteroplasty. Some advocate merely approximating the muscles, but if possible, the author prefers to overlap the muscle ends, thus performing an overlapping sphincteroplasty. This is done by placing numerous mattress sutures through the entire length of the sphincter on each side (Fig. 100–7). Approximately six sutures (three on each side) are used. Mattress-type sutures are utilized to overlap the edges of the sphincter (Figs. 100–8 through 100–10). During the repair, irrigation of the wound is carried out with an antibiotic solution.

5. Frequently a perineorrhaphy needs to be performed (see Fig. 100–9). Also, if necessary, a distal levatorplasty may be performed to decrease the size of the vaginal introitus. At the completion of the repair, the anal canal should be tightened so that it allows just an index finger to be admitted.

6. The skin edges are then closed with interrupted 3-0 absorbable sutures. The author does not routinely place a drain in this area. Patients are maintained on stool softeners throughout the postoperative period.

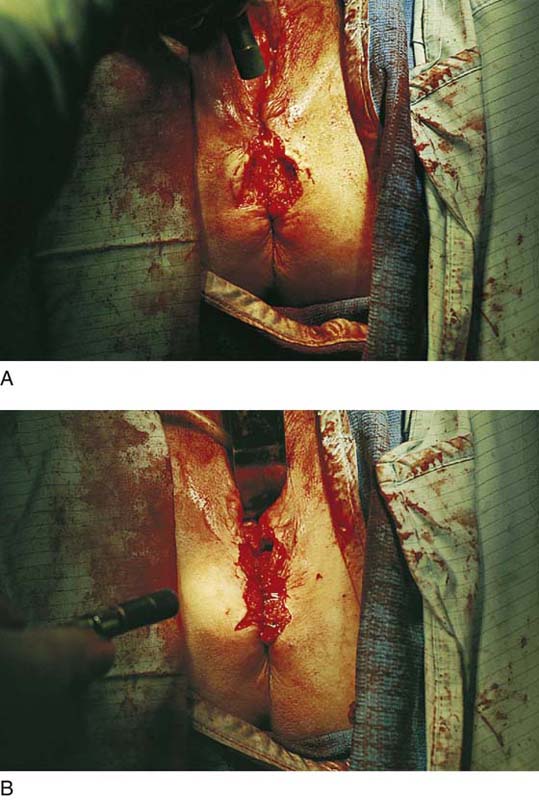

If the ends of the anal sphincter are significantly refracted, then it becomes impossible to perform an overlapping sphincteroplasty. This is commonly seen when there is complete breakdown of a third- or fourth-degree episiotomy repair. Fig. 100–11A portrays a 28-year-old patient who is approximately 3 months postpartum after breakdown of a fourth-degree episiotomy repair, who presented with significant fecal incontinence. Note that there is complete loss of the perineal body with significant retraction of the external anal sphincter. The technique of an end-to-end sphincteroplasty with incorporation of the internal anal sphincter is demonstrated in Figs. 100–11 and 100–12.

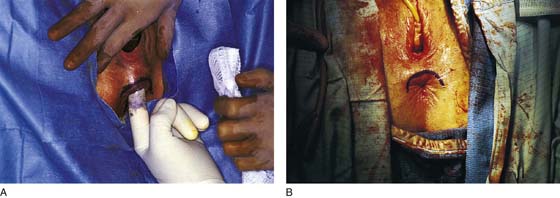

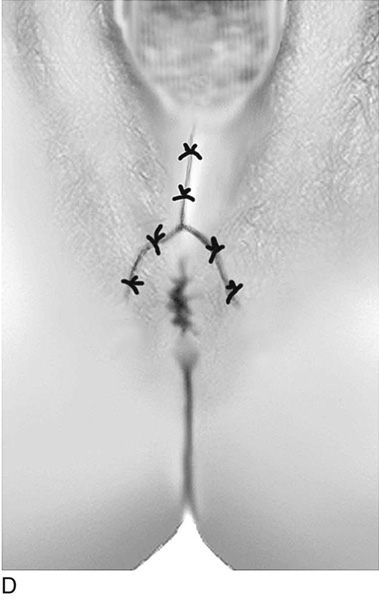

FIGURE 100–2 Examination demonstrated an attenuated perineal body with a deficient anal sphincter anteriorly.

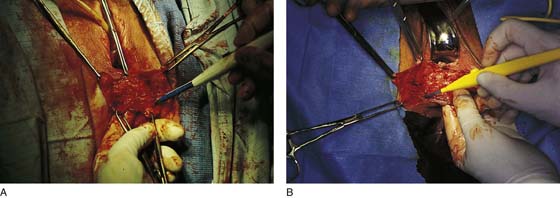

FIGURE 100–3 A and B. An inverted-U incision is made from approximately 9 o’clock to 3 o’clock to allow exposure and identification of the retracted edges of the external anal sphincter.

FIGURE 100–4 Allis clamps are used for traction and indicate the approximate location of the retracted edges of sphincter.

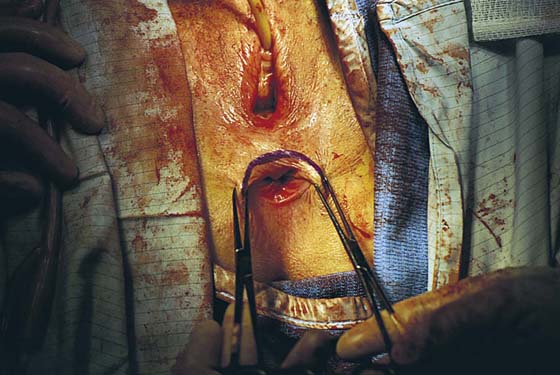

FIGURE 100–5 A and B. Sharp dissection mobilizes the perineal skin off the anterior rectal wall.

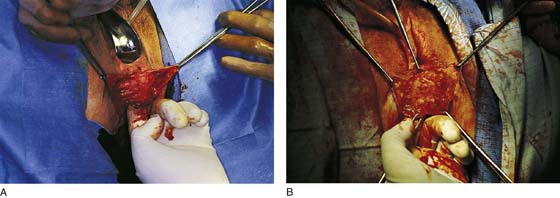

FIGURE 100–6 A. Dissection is extended laterally to expose the external sphincter. A nerve stimulator is used to identify viable muscle on the left side. B. Low-voltage cautery is used to identify viable muscle on the right side.

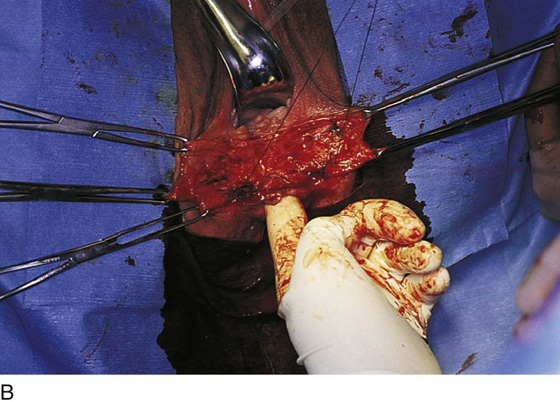

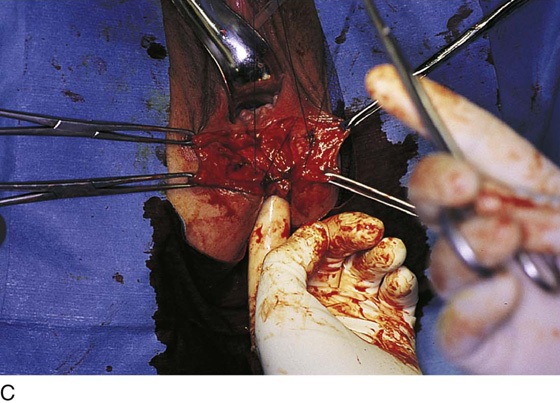

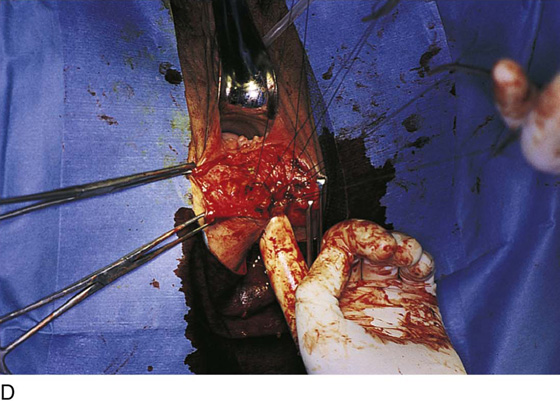

FIGURE 100–7 A through D. Sutures are passed through the retracted edges of the external anal sphincter on each side. Numerous sutures are placed over a 3- to 4-cm distance up the anal canal. Note that small bites incorporate the anterior rectal wall into the repair.

FIGURE 100–8 Note that tying of the sutures approximates the ends of the external anal sphincter. Whenever possible, an overlapping sphincteroplasty is performed in a “vest-over-pants” fashion.

FIGURE 100–9 The perineal body is rebuilt, and the perineal skin is approximated at the midline. Upon completion of the repair, the diameter of the anal canal should allow tight placement of an index finger.

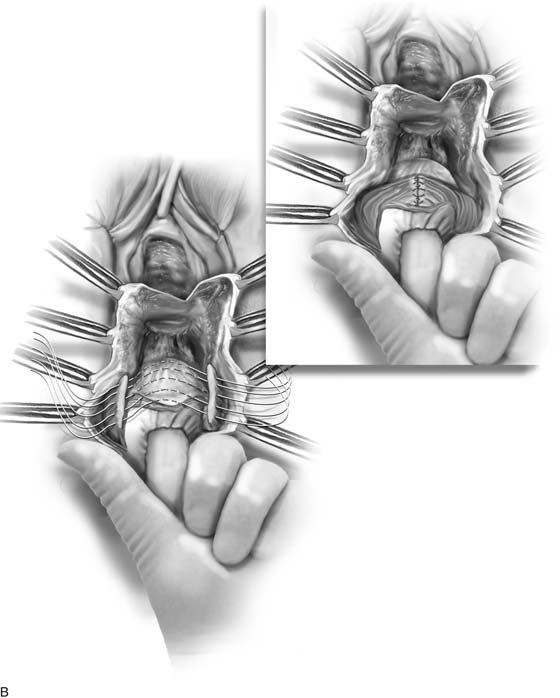

FIGURE 100–10 A through D. Technique of overlapping sphincteroplasty.

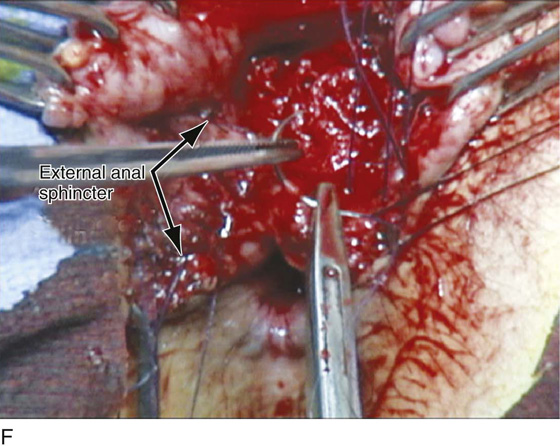

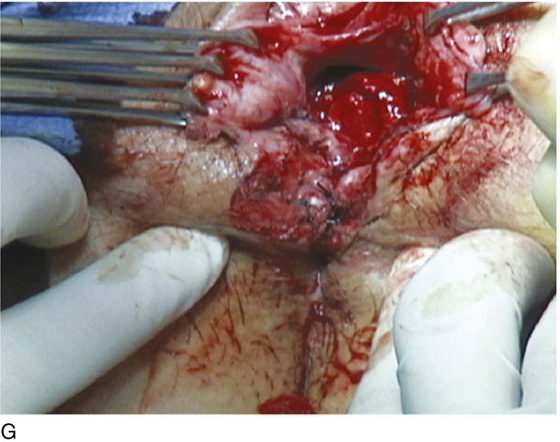

FIGURE 100–11 Technique of an end-to-end sphincteroplasty in a patient who sustained a breakdown of a fourth-degree episiotomy repair. A. Note the widened vaginal hiatus, the patulous anal opening, and complete loss of the perineal body with significant retraction of the ends of the anal sphincter. B. An inverted-U incision is made. C. The incision is extended laterally and inferiorly to identify the retracted ends of the external sphincter. D. Viable muscle is identified at approximately 3 o’clock on the left side. E. The retracted end of the external anal sphincter is identified on the left side. F. The external anal sphincter on the right is demonstrated. Note that the dissected sphincter is approximately 4 cm wide. Numerous sutures have been passed through the left end of the external sphincter. As each suture is passed to the opposite side, small bites are taken through the internal anal sphincter. G. Sutures have been tied across the midline, completing the end-to-end sphincteroplasty. H. The perineal body has been rebuilt, and the completed repair is shown.

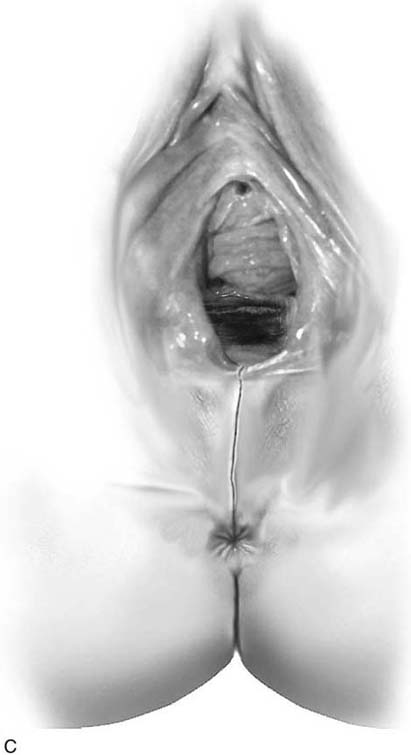

FIGURE 100–12 Technique of end-to-end sphincteroplasty with perineal reconstruction. A. A cloacal perineal defect is noted in which the posterior vaginal wall and the anterior rectal wall are fused. An inverted-U or transverse incision is made (inset). B. The rectovaginal space has been opened, along with the posterior vaginal wall of the rectum. The retracted ends of the external anal sphincter have been identified. Sutures incorporate small bites through the internal anal sphincter as they are passed to the opposite side. The completed end-to-end sphincteroplasty is shown (inset). C. The perineum has been completely reconstructed. The completed repair should show a perpendicular relationship between the posterior vaginal wall and the rebuilt perineum. Note that the anal opening becomes puckered and is no longer patulous.