78 Supraventricular Arrhythmias

Classification and Epidemiology

Classification and Epidemiology

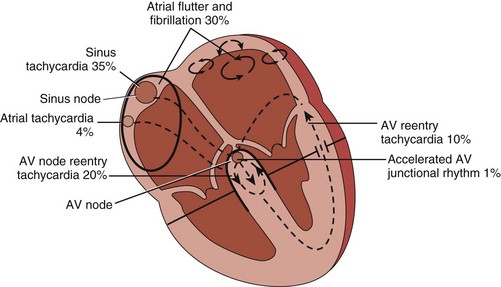

Supraventricular arrhythmias include rhythms arising from the sinus node and the adjacent atrial tissue (inappropriate sinus tachycardia, sinoatrial reentry tachycardia), both the right and left atria (atrial tachycardia, flutter, and fibrillation), the atrioventricular (AV) node (AV nodal reentry tachycardia, accelerated ectopic junctional rhythm), and the AV node, with involvement of an accessory pathway or multiple pathways (AV reentry tachycardia) (Figure 78-1).

Figure 78-1 Supraventricular tachyarrhythmias encountered in the emergency setting. AV, atrioventricular.

Atrioventricular Nodal Reentry Tachycardia and Atrioventricular Reentry Tachycardia

AV nodal reentry tachycardia and AV reentry tachycardia are usually referred to as paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias and are often seen in young patients with little or no structural heart disease, although a congenital heart abnormality giving rise to increased atrial pressure and dilatation (e.g., Ebstein’s anomaly, atrial septal defect, Fallot’s tetralogy) can coexist in a small percentage of patients with these arrhythmias.1 The first presentation is common between age 12 and 30 years, and the prevalence is approximately 2.5 per 1000. Women are twice as likely as men to present with AV nodal reentry tachycardia.

Atrial Flutter and Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation is the most common supraventricular arrhythmia, affecting 1% to 2% of the general population, especially the elderly. It is usually associated with cardiovascular pathologies, among which hypertension and congestive heart failure prevail.2 About a third of patients, however, present with no underlying heart disease and are considered to have “lone” atrial fibrillation. The epidemiology of isolated atrial flutter is largely unknown and is believed to be in the range of 0.037% to 0.88% per 1000 person-years, but at least half these patients also have atrial fibrillation as a coexistent arrhythmia.

Electrocardiography

Electrocardiography

Narrow-Complex Tachycardias

The typical ECG feature is narrow QRS complexes less than 120 msec. In this case, the tachycardia is almost always supraventricular, and the differential diagnosis relates to its mechanism (Figure 78-2).

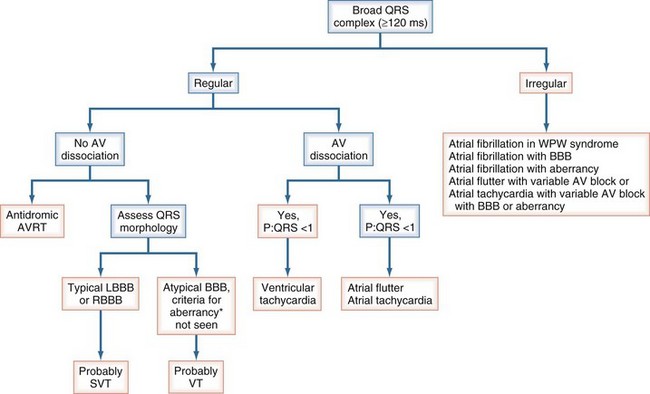

Wide-Complex Tachycardias

The differential diagnostic features of wide-complex tachycardias favoring a supraventricular origin of the arrhythmia include, but are not limited to, preexistent bundle branch block; rate-dependent aberrancy; antidromic AV reentry tachycardia, when an accessory pathway conducts and excites the ventricles antegradely; and prominent electrolyte abnormalities (e.g., hypokalemia) or heart muscle disease (cardiomyopathy), all of which may result in QRS widening (Figure 78-3). If the diagnosis of supraventricular tachycardia cannot be proved, the patient should be treated as if ventricular tachycardia is present. Immediate direct-current (DC) cardioversion is the treatment for any hemodynamically unstable tachycardia.

Atrioventricular Nodal Reentry Tachycardia

Atrioventricular Nodal Reentry Tachycardia

Electrocardiographic Presentation

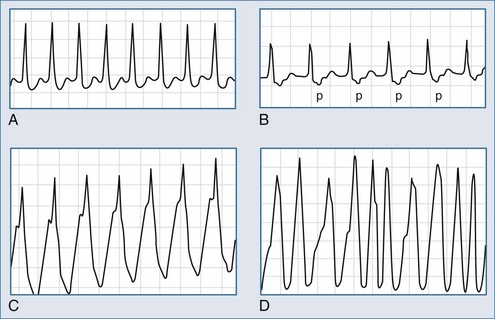

In sinus rhythm, the ECG is usually normal unless other unrelated abnormalities are present. During AV nodal reentry tachycardia, the rhythm is regular, with narrow QRS complexes and a rate of 140 to 250 beats per minute. The atria are activated retrogradely, producing the inverted P waves in leads II, III, and aVF. Because atrial and ventricular depolarization occurs simultaneously, the P waves are often obscured by the QRS complexes and cannot be detected on the surface ECG (Figure 78-4, A). However, in about a third of cases of slow-fast AV nodal reentry tachycardia, a terminal positive deflection in lead aVR or V1 (or both), imitating right bundle branch block or pseudo-S waves in the inferiorly oriented leads, may be present, reflecting retrograde activation of the atria. Tachycardia using these pathways in reverse (“fast-slow,” or long RP, tachycardia) is less common (5%-10% of cases).

Atrioventricular Reentry Tachycardia

Atrioventricular Reentry Tachycardia

Mechanism and Electrocardiographic Presentation

The reentry circuit of orthodromic AV reentry tachycardia involves the AV node and an accessory pathway, with the impulses conducting from the atria to the ventricles over the AV node and traveling in the reverse direction through the accessory pathway (see Figure 78-4, B). In antidromic AV reentry tachycardia, the reentrant impulses conduct antegradely from the atria to the ventricles via an accessory pathway and retrogradely via the AV node or a second accessory pathway (see Figure 78-4, C). Antidromic AV reentry tachycardia is uncommon (<10% of cases). Atrial fibrillation is usually encountered in patients with antegradely conducting pathways (see Figure 78-4, D).

Acute Management

In an emergency, distinguishing between AV nodal reentry tachycardia and AV reentry tachycardia may be difficult, but it is usually not critical, because both tachycardias respond to the same treatment. If the patient is hemodynamically stable, vagal maneuvers including carotid sinus massage, Valsalva maneuver, and facial immersion in cold water (diving reflex) can terminate tachycardia in about 50% of patients (Box 78-1).3,4 Commercially available gel packs can be used as cold compresses instead of facial immersion, but the most important element is wet nostrils and breath-holding.

Box 78-1

Vagal Maneuvers to Terminate Tachycardia

Carotid Sinus Massage

Valsalva Maneuver

Pharmacologic Termination

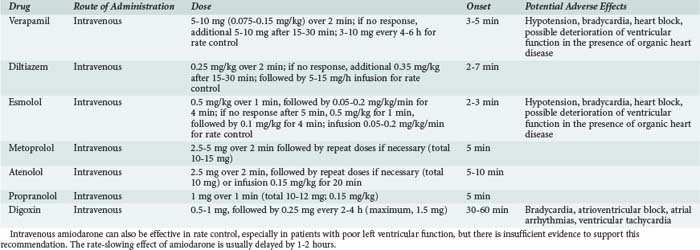

AV blocking agents such as adenosine, verapamil, diltiazem, and beta-blockers are effective in terminating both AV nodal reentry and AV reentry tachycardia (Table 78-1).1

Adenosine

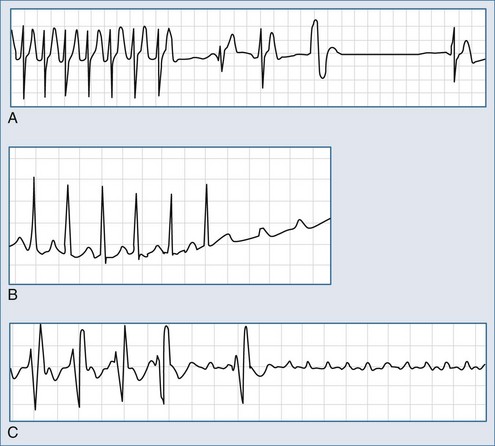

Intravenous (IV) adenosine is effective in diagnosing, rate slowing, and often terminating narrow-complex tachycardias.5 Adenosine usually terminates AV nodal reentry tachycardia and AV reentry tachycardia but rarely interrupts the atrial flutter circuit and does not suppress automatic atrial tachycardia; it can, however, produce high-degree AV block during which the tachycardia persists (Figure 78-5). It has no effect on most ventricular tachycardias. Adenosine is advantageous compared with verapamil because of its rapid onset and the absence of a negative inotropic effect in patients with poor left ventricular function and those with significant hypotension.

Adenosine is administered as a very rapid 3- to 6-mg IV bolus; if this is ineffective, another 6- to 12-mg bolus can be given 2 to 5 minutes later. Adenosine is metabolized very quickly, with an effective half-life of 10 seconds. Adverse effects including dyspnea, facial flushing, and chest tightness are therefore short-lived, but in about 12% of patients, adenosine may shorten the atrial effective refractory period and provoke atrial flutter or fibrillation or accelerate conduction over the accessory pathway and produce a rapid ventricular response. In a proportion of patients, ventricular premature beats and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia may occur after the successful termination of supraventricular tachycardia.6 Some individuals, particularly heart transplant recipients, are unusually sensitive to adenosine and require a lower dose (1 mg).

Verapamil and Diltiazem

Verapamil is administered IV as a 5- to 10-mg bolus over 2 minutes, and the effect on tachycardia is expected in 5 to 10 minutes. If necessary, a second bolus of 10 mg can be given 30 minutes after the initial dose. Vagal maneuvers can be effective at this stage. Verapamil should not be used for wide-complex tachycardias. IV verapamil is contraindicated in patients with poor left ventricular function or heart failure, and it should not be administered after pretreatment with oral and especially IV beta-blockers. It should not be used for atrial fibrillation associated with preexcitation syndrome, because it may result in acceleration of conduction over an antegradely conducting accessory pathway (especially with a short effective refractory period) a rapid ventricular response, and ventricular fibrillation. Diltiazem is an alternative to verapamil, but lower effective rates have been reported with this drug.7 Diltiazem has the same contraindications as verapamil.

Beta-Blockers

Among beta-blockers, esmolol, administered as an IV infusion at a rate of 50 to 200 µg/kg/min, is the agent of choice because of its rapid onset. More readily available IV metoprolol, atenolol, and propranolol can also be considered (see Table 78-1). Excessive bradycardia caused by AV node blocking agents can be countered with IV injection of atropine, 0.6 to 2.4 mg in divided doses of 0.6 mg.

Accelerated Atrioventricular Rhythm

Accelerated Atrioventricular Rhythm

Accelerated AV rhythm is produced by abnormal automaticity in the AV node. It is a narrow QRS complex tachycardia (unless bundle branch block is present), with the ventricular rate ranging from 70 to 250 beats per minute. AV dissociation is also present, because the atria are activated normally by the sinus node impulse while the ventricles are depolarized from an accelerated junctional site (Figure 78-6). This arrhythmia is commonly due to digitalis toxicity, and drug withdrawal is the usual therapy. If the rate of the AV node pacemaker is not fast, atropine can be given to increase the sinus node discharge until it resumes its dominance.

Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter

Atrial Fibrillation and Atrial Flutter

Atrial Flutter

Mechanism

The classification of atrial flutter is based on the ECG presentation and electrophysiologic mechanisms. The most common type is typical isthmus-dependent atrial flutter. Incisional reentry atrial flutter occurs after surgical correction for congenital heart disease. There are also various forms of atypical flutters, such as atypical right atrial isthmus-dependent flutter (double-wave and lower loop reentry) and left atrial flutter, whose circuit contains the pulmonary vein or mitral valve annulus.8

Electrocardiographic Presentation

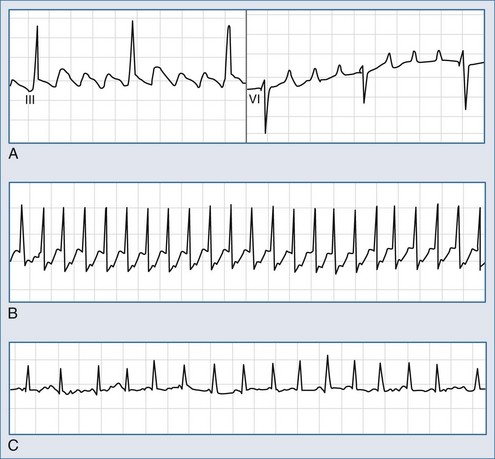

Atrial flutter is usually an organized atrial rhythm with an atrial rate typically between 250 and 350 beats per minute. In the more common counterclockwise flutter, F waves are negative in leads II, III, aVF, and V5-6 and positive in leads V1-2 (Figure 78-7, A). Typical clockwise atrial flutter is characterized by positive F waves in leads II, III, and aVF and negative waves in leads V1-2.

Treatment with propafenone, flecainide, and amiodarone to prevent recurrent atrial fibrillation without adding an AV blocking agent (beta-blocker or nondihydropyridine calcium antagonist) can organize the arrhythmia into typical atrial flutter with AV conduction of 1 : 1 or 2 : 1, producing a ventricular rate response of 150 beats per minute or higher (see Figure 78-7, B). The probability of 1 : 1 conduction is increased in the presence of an accessory pathway with a short effective refractory period.

Atrial Fibrillation

Electrocardiographic Presentation

Atrial fibrillation is defined as rapid oscillations or fibrillatory f waves that vary in size, shape, and timing (see Figure 78-7, C). The ventricular response rate is variable and depends on the rate and regularity of atrial activity, the refractory properties of the AV node itself, and the balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic tone. The RR intervals are irregular unless the patient has complete AV block or a paced rhythm.

Acute Management

Rate Control

Rate control is pertinent to all atrial tachyarrhythmias, particularly if restoration of sinus rhythm is deferred. IV verapamil, diltiazem, and beta-blockers can rapidly control the ventricular response rate in atrial fibrillation2 (see Table 78-1), but the efficacy may be less in atrial flutter. The decrease in the ventricular rate (approximately 20%-30%), time to maximal effect (20-30 minutes), conversion rate (12%-25%), and adverse reactions (usually hypotension and bradycardia, although left ventricular dysfunction and high-degree heart block may occur) are reportedly similar with both classes of drugs. Beta-blockers are preferable if thyrotoxicosis is suspected as a cause of the arrhythmia.

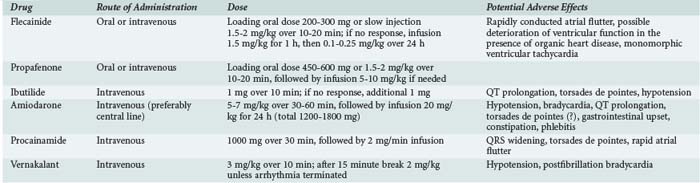

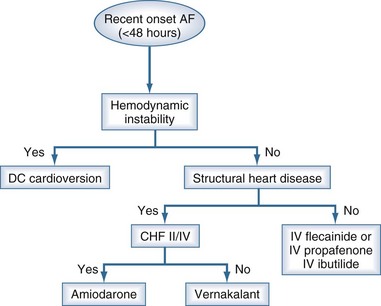

Pharmacologic Cardioversion

Flecainide and Propafenone

Pharmacologic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation can be accomplished with the IC class of antiarrhythmic drugs—flecainide and propafenone administered orally as a single dose of 300 and 600 mg, respectively (Table 78-2).2 Placebo-controlled randomized studies show an efficacy rate of 60% to 80% between the third and eighth hour after drug ingestion.9,10 Both oral and IV routes of administration are equally effective, although with IV injection, restoration of sinus rhythm can be achieved more quickly.

Ibutilide

The class III agent, ibutilide, is administered IV as a 10-minute injection of 1 to 2 mg and is particularly effective in terminating atrial flutter, with a success rate of about 60%. Its administration may be associated with excessive QT interval prolongation, however, because of the rapid delayed rectifier potassium current (IKr) blockade and the risk of torsades de pointes.11,12 It is less effective in atrial fibrillation. Higher doses of ibutilide administered as two successive infusions of 1 mg are usually required to terminate fibrillation. The advantage of ibutilide is that it may be effective in the conversion of arrhythmias of up to 30 days’ duration, but the success rate drops significantly to 20% to 30%. The safety of ibutilide in patients with poor left ventricular function is unknown.

Amiodarone

Amiodarone administered IV at a dose of 5 mg/kg for 1 hour, followed by an infusion of 20 mg/kg over 24 hours, is effective in converting both atrial fibrillation and flutter, but the effect is significantly delayed.13,14 However, because of its ability to control the ventricular rate, a low likelihood of torsades de pointes, and the absence of a negative inotropic effect, amiodarone can be used safely in patients with significant structural heart disease and those who are critically ill.

Procainamide and Sotalol

Procainamide administered as a slow IV injection of 1000 mg over 20 to 30 minutes, followed if necessary by an infusion of 2 mg/min over 1 hour, converts atrial flutter or fibrillation of less than 48 hours’ duration, but its efficacy is limited in longer-lasting arrhythmias.15 It is less effective than propafenone, flecainide, and ibutilide.

Vernakalant

This drug is given by a short IV infusion (3 mg/kg over 10 minutes). If after a 15-minute waiting period the arrhythmia persists, a second infusion of 2 mg/kg may be given over 10 minutes. In recent-onset atrial fibrillation (<72 hours), about 50% of cases will terminate on average 12 minutes from the start of the first infusion. Vernakalant may be given to patients with underlying structural heart disease but not to patients with grade II/IV congestive heart failure. Proarrhythmia is uncommon, but hypotension and posttermination bradycardia may occur.16

The choice of an antiarrhythmic agent for cardioversion is illustrated in Figure 78-8.

Anticoagulation

Anticoagulation is imperative if the arrhythmia persists for more than 24 to 48 hours or if its duration is unknown. Atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation pose similar risks of thromboembolism, and the same criteria for anticoagulation should be applied in patients with either arrhythmia. In hemodynamically stable arrhythmias of more than 48 hours’ or of unknown duration, rate control and 3 weeks’ anticoagulation with warfarin (International Normalized Ratio 2.0 to 3.0) should be considered before any intervention (electrical or pharmacologic cardioversion, catheter ablation).17

Transesophageal Echocardiography–Guided Cardioversion

If, for any reason, deferral of cardioversion is not indicated, the transesophageal echocardiography–guided approach, with short-term anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin, is a safe and effective alternative.18 It may be clinically beneficial in patients with recent-onset arrhythmias or in individuals at high risk of bleeding complications during prolonged anticoagulation therapy.19 Compared with unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin therapy does not involve prolonged IV administration or laboratory monitoring and therefore has the potential to greatly simplify cardioversion-related anticoagulation therapy in low-risk individuals. Postcardioversion anticoagulation should be considered if atrial fibrillation has been present for 48 hours or more, or if thromboembolic risk factors are present (Table 78-3).17,20

TABLE 78-3 Risk Stratification and Indications for Anticoagulation in Atrial Fibrillation and Flutter

| Risk of Stroke | Definition | Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Low (1%/yr) | Age < 65 yr; ejection fraction ≥ 0.50; no stroke or transient ischemic attack, hypertension, heart failure, or valvular heart disease | Aspirin 325 mg |

| Low to moderate (1.5%/yr) | Age 65-75 yr; no risk factors | Aspirin 325 mg |

| Moderate to high (2.5%/yr) | Age 65-75 yr and either diabetes or coronary heart disease | Warfarin (INR 2.0-3.0) |

| High (6%/yr) | Age < 75 yr and hypertension, heart failure, or ejection fraction < 0.50 | Warfarin (INR 2.0-3.0) |

| Age > 75 yr, particularly women, even in the absence of risk factors | ||

| Very high (10%/yr) | Age > 75 yr and hypertension, heart failure, or ejection fraction < 0.50 | Warfarin (INR 2.0-3.0) |

| Any age with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack or valvular heart disease |

INR, International Normalized Ratio.

Modified from Straus SE, Majumdar SR, McAlister FA. New evidence for stroke prevention: scientific review. JAMA 2002;288:1388-95.

Atrial Tachycardia

Atrial Tachycardia

Electrocardiographic Presentation

The heart rate varies from 120 to 250 beats per minute, P waves precede the QRS complex, and PP intervals are regular (see Figure 78-5, B). The PR interval is linked to the rate of tachycardia and is longer than in sinus rhythm at the same rate. P wave morphology is usually different from that during sinus rhythm and depends on the site of origin. Left atrial tachycardia presents with the negative P waves in leads I, aVL, V5, and V6. Automatic atrial tachycardia may present as an incessant variety, leading to tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy

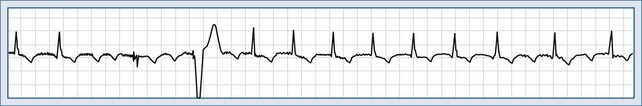

Atrial Tachycardia With Atrioventricular Block

Tachycardia with AV block occurs commonly in patients with organic heart disease, and in 50% to 75% of cases, it is due to digitalis toxicity (Figure 78-9). Digoxin-specific antibody fragments are available for the reversal of life-threatening overdosage.

Acute Management

It is generally accepted that beta-blockers and calcium antagonists, particularly verapamil, can either terminate the tachycardia or produce rate control. Adenosine can terminate atrial tachycardia, but the most common response to adenosine is to create AV block and thereby reveal the unaffected tachycardia (see Figure 78-5, B and C).

Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia

Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia

Inappropriate sinus tachycardia is a persistent increase in resting heart rate unrelated to or out of proportion with the level of physical or emotional stress. It is found predominantly in women and is not uncommon in health professionals. Sinus tachycardia due to intrinsic sinus node abnormalities such as enhanced automaticity or abnormal autonomic regulation of the heart, with excess sympathetic and reduced parasympathetic input, is not unusual. The main therapy is beta-blockers, although ivabradine, a drug which blocks the main current responsible for diastolic depolarization in the sinus node, is being increasingly used in Europe.21 In general, sinus tachycardia is a secondary phenomenon, and the underlying causes should be actively investigated. Depending on the clinical setting, acute causes include fever, hypotension, infection, anemia, thyrotoxicosis, hypovolemia, acute heart failure, acute pulmonary embolism, and shock. Sinus tachycardia may be associated with the abuse of drugs such as amphetamines.

Key Points

Albers GW, Dalen JE, Laupacis A, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2001;119:194S-206S.

Blomström-Lundvist C, Scheiman MM, Aliot EM, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias—executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1493-1531.

Camm AJ. Atrial fibrillation: is there a role for low-molecular-weight heparin? Clin Cardiol. 2001;24:I15-I19.

Fuster V, Rydén LE, Asinger RV, et al. Task force report: ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1852-1923.

Mehta D, Wafa S, Ward DE, Camm AJ. Relative efficacy of various physical manoeuvres in the termination of junctional tachycardia. Lancet. 1988;1:1181-1185.

1 Blomström-Lundvist C, Scheiman MM, Aliot EM, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias—executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1493-1531.

2 Fuster V, Rydén LE, Asinger RV, et al. Task force report: ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1852-1923.

3 Mehta D, Wafa S, Ward DE, et al. Relative efficacy of various physical manoeuvres in the termination of junctional tachycardia. Lancet. 1988;1:1181-1185.

4 Wen ZC, Chen SA, Tai CT, et al. Electrophysiological mechanisms and determinants of vagal maneuvers for termination of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1998;98:2716-2723.

5 DiMarco JP, Miles W, Akhtar M, et al. Adenosine for paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia: Dose ranging and comparison with verapamil. Assessment in placebo-controlled, multicenter trials. The Adenosine for PSVT Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:104-110.

6 Tan HL, Spekhorst HH, Peters RJ, et al. Adenosine induced ventricular arrhythmias in the emergency room. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2001;24:450-455.

7 Dougherty AH, Jackman WM, Naccarelli GV, et al. Acute conversion of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia with intravenous diltiazem. IV Diltiazem Study Group. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:587-592.

8 Saoudi N, Cosio F, Waldo A, et al. A classification of atrial flutter and regular atrial tachycardia according to electrophysiological mechanisms and anatomical bases: a statement from a Joint Expert Group from the Working Group of Arrhythmias of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1162-1182.

9 Boriani G, Biffi M, Capucci A, et al. Conversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm: Effects of different drug protocols. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:2470-2474.

10 Bianconi L, Mennuni M. PAFIT-3 investigators: comparison between propafenone and digoxin administered intravenously to patients with acute atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:584-588.

11 Stambler BS, Wood MA, Ellenbogen KA, et al. Efficacy and safety of repeated intravenous doses of ibutilide for rapid conversion of atrial flutter or fibrillation. Circulation. 1996;94:1613-1621.

12 Volgman AS, Carberry PA, Stambler B, et al. Conversion efficacy and safety of intravenous ibutilide compared with intravenous procainamide in patients with atrial flutter or fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1414-1419.

13 Vardas PE, Kochiadakis GE, Igoumenidis NE, et al. Amiodarone as a first-choice drug for restoring sinus rhythm in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized, controlled study. Chest. 2000;117:1538-1545.

14 Chevalier P, Durand-Dubief A, Burri H, et al. Amiodarone versus placebo and classic drugs for cardioversion of recent-onset atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:255-262.

15 Kochiadakis GE, Igoumenidis NE, Solomou MC, et al. Conversion of atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm using acute intravenous procainamide infusion. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1998;12:75-81.

16 Kowey PR, Dorian P, Mitchell LB, Pratt CM, Roy D, Schwartz PJ, et al. Atrial Arrhythmia Conversion Trial Investigators. Vernakalant hydrochloride for the rapid conversion of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Dec;2(6):652-659.

17 Albers GW, Dalen JE, Laupacis A, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2001;119(1 Suppl):194S-206S.

18 Roijer A, Eskilsson J, Olsson B. Transesophageal echocardiography guided cardioversion of atrial fibrillation or flutter: selection of a low-risk group for immediate cardioversion. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:837-847.

19 Camm AJ. Atrial fibrillation: is there a role for low-molecular-weight heparin? Clin Cardiol. 2001;24(3 Suppl):I15-I19.

20 Straus SE, Majumdar SR, McAlister FA. New evidence for stroke prevention: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288:1388-1395.

21 Calò L, Rebecchi M, Sette A, Martino A, de Ruvo E, Sciarra L, et al. Efficacy of ivabradine administration in patients affected by inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Heart Rhythm. 2010 Sep;7(9):1318-1323.