CHAPTER 30 Superior Pedicle Extension Mastopexy

Key Points

Indications

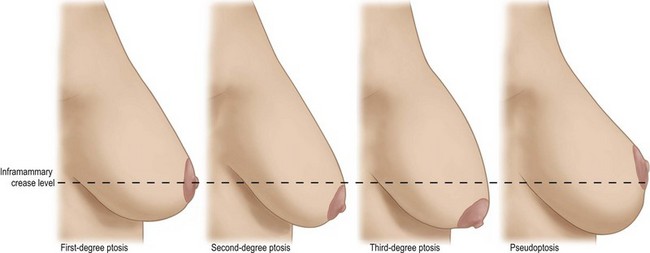

Speaking generally, ptosis refers to relative descent of the NAC in relation to the breast mound with elongation of the distance between the nipple and suprasternal notch. The historical classification system used to define ptosis was elaborated by Regnault and defines three degrees of ptosis based on the relationship of the nipple to the inframammary fold (Fig. 30.1). A situation where the nipple lies at the level of the inframammary fold but above the level of glandular tissue is called first degree ptosis. In these cases, an augmentation mammaplasty is often adequate to correct the condition. In second degree ptosis, the nipple lies below the level of the submammary fold but above the lower contour of breast tissue. Third degree ptosis is characterized by a nipple located below the inframammary fold and at the lowest contour of the breast. Both second and third degree ptosis require some degree of skin reduction and tissue rearrangement for correction. Patients with this degree of ptosis are deemed appropriate mastopexy candidates. The condition of pseudoptosis is unique in that the nipple remains above the inframammary fold but the skin and glandular elements have fallen below the crease. This is usually corrected with augmentation.

Fig. 30.1 Degrees of breast ptosis based on nipple position relative to inframammary crease.

Reprinted with permission from Boehm KA, Nahai F. Mastopexy. In: Nahabedian MY, editor. Cosmetic and reconstructive breast surgery, A volume in the Procedures in Reconstructive Surgery series. New York: Saunders; 2009.

Operative Techniques

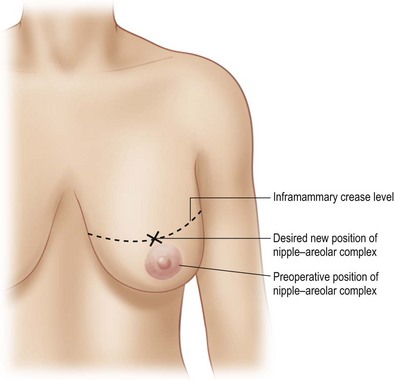

To determine the desired nipple position, an index finger is placed in the inframammary crease and this level transposed anteriorly onto the previously marked breast meridian (Fig. 30.2). Again, this distance usually is somewhere between 10 and 14 cm from the sternal midline and 18–22 cm from the suprasternal notch. These markings should be compared between the right and left sides and adjusted as needed to achieve symmetry.

Fig. 30.2 Preoperative determination of nipple–areolar placement.

Reprinted with permission from Boehm KA, Nahai F. Mastopexy. In: Nahabedian MY, editor. Cosmetic and reconstructive breast surgery, A volume in the Procedures in Reconstructive Surgery series. New York: Saunders; 2009.

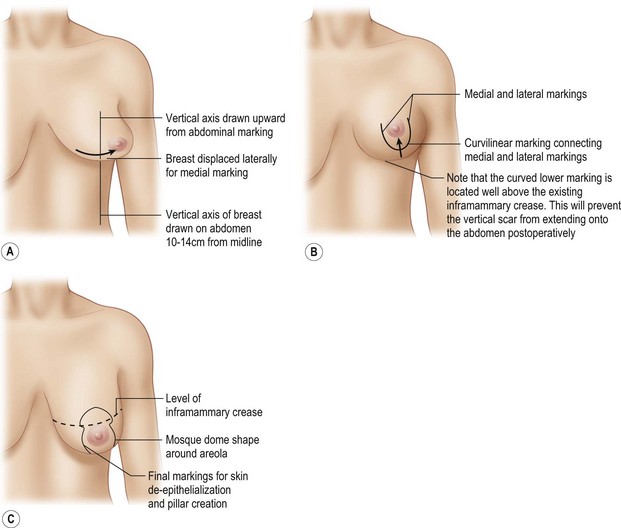

Attention is now directed to marking the medial and lateral pillars which will ultimately support the elevated breast. To mark the medial line, the breast is pushed laterally and the line denoting the vertical axis of the breast on the upper abdomen now continued superiorly onto the breast mound itself (Fig. 30.3). The same technique is used to draw the lateral line but the breast is pushed medially. It is often best to be somewhat conservative in pushing the breast medially and laterally to denote vertical lines. As most breast parenchyma is preserved, overzealous skin removal can create undue tension across the vertical closure resulting in poor scarring or wound breakdown. These two lines are now connected by a curved marking made 1–3 cm above the existent crease. If this line is placed too low, the resultant vertical scar will conspicuously extend onto the upper abdomen.

Fig. 30.3 Marking the medial and lateral pillars.

Reprinted with permission from Boehm KA, Nahai F. Mastopexy. In: Nahabedian MY, editor. Cosmetic and reconstructive breast surgery, A volume in the Procedures in Reconstructive Surgery series. New York: Saunders; 2009.

A curved line is also used to connect the medial and lateral markings at their superior border, with the ellipse extending about 2 cm above the desired postoperative position for the nipple (Fig. 30.4). The length of the periareolar marking should range from 14 to 16 cm to prevent a large discrepancy in size between the preserved areola and the newly marked opening. This will minimize periareolar skin redundancy and facilitate closure. Additionally, when marking the new desired point for the superior border of the areola, it should be placed just at the level of the inframammary crease. This will minimize the risk of a high riding nipple postoperatively. The areola to be preserved is marked with a 38–42 mm cookie cutter, without putting the areola or breast skin on any stretch.

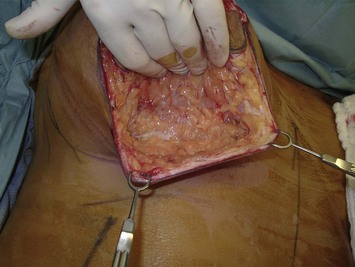

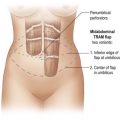

The procedure itself is undertaken under general anesthesia with the patient supine, arms abducted 90 degrees and adequately secured in anticipation of the sitting position later in the case. For both vasoconstriction and hydrodissection, 0.5% lidocaine with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine can be infiltrated into the skin between the medial and lateral markings, sparing the area immediately supplying the NAC. A mammostat is placed around the base of the breast to aid in handling the breast as well as minimizing blood loss (Fig. 30.5). The skin between the preserved areola and previously made markings is now completely de-epithelialized. With the mammostat released, the medial and lateral markings along the de-epithelialized lower pole are now incised down to the level of the pectoralis fascia (Fig. 30.6). This is done by directing a 10 blade perpendicular to breast tissue down to the fascia. Along the lower breast, hooks are used to elevate the skin edges such that a flap of 1–1.5 cm thickness is elevated with electrocautery down to the level of the marked native inframammary crease (Fig. 30.7). At the level of the crease, the cautery is redirected perpendicular to the chest wall such that the incision is once again carried through breast tissue to pectoralis fascia.

Fig. 30.6 Incising the lower pole tissue according to the medial and lateral pillars marked preoperatively.

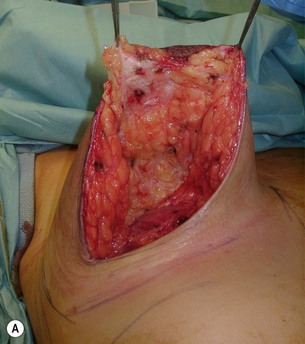

Now freed along its medial, lateral and inferior edges, this de-epithelialized inferior pole parenchyma is elevated at the level of the pectoralis fascia using the electrocautery. This elevation extends from the inframammary crease, deep to and past the areola and into the superior pole. In this way, a retroareolar pocket is created. Vascularity to the NAC is provided by the intact superiorly based dermoglandular elements. While in a breast reduction, this now elevated inferior tissue would be sharply excised, in the case of a mastopexy it is used to recreate projection and medial cleavage by transposing it into the newly created retroareolar pocket (Fig. 30.8). An Allis clamp is used to position this tissue high in the superior pole and 2-0 Vicryl sutures are used to tack the parenchyma to the sturdy pectoralis fascia. If additional volume is necessary, an implant can be placed in either the subglandular or subpectoral position at this point in the procedure.

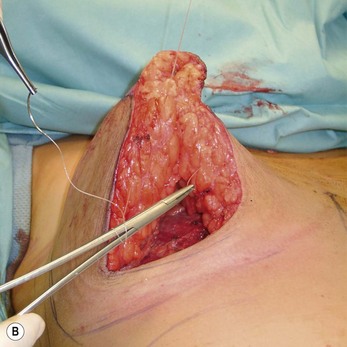

The newly created lower pole medial and lateral pillars are now brought together to prevent descent of the NAC. A 7 mm Blake drain is placed to obliterate the dead space behind the two pillars and evacuate any fluid which might accumulate and put tension on the vertical closure. The columns are then reapproximated in two layers with 2-0 Vicryl sutures extending from the base of the areola to the inferior skin edge (Fig. 30.9A, B). If any size discrepancy exists between the two sides, some parenchymal resection can be performed on the pillars or tacked tissue to equalize the volumes. These sutured pillars serve as a stable column of breast tissue which the NAC rests upon, keeping it adequately supported in its newly elevated position. Bringing these pillars together will also effectively narrow the base of the breast diameter.

The areola is inset first with a layer of interrupted 3-0 Monocryl dermal sutures followed by a 4-0 Monocryl intracuticular suture. The skin margins along the vertical limb are also closed with a layer of 3-0 Monocryl dermal sutures. No undermining of the skin edges is done so as to minimize risk of tissue ischemia and incisional break-down. The most inferior aspect of the vertical scar is closed as a purse string and then run as an intracuticular suture along the remaining length of the vertical scar, pulling tight along the way to gather the redundant skin edges and shorten the scar (Fig. 30.10).

Smith DJJr, Palin WEJr, Katch VL, et al. Breast volume and anthropomorphic measurements: normal values. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:331.

American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2006. Percent of change in select procedures: 1997–2006

Berthe JV, Massaut J, Greuse M, et al. The vertical mammaplasty: a reappraisal of the technique and its complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:2192-2199.

Boehm KA, Nahai F. Mastopexy. In: Nahabedian M, editor. Cosmetic and reconstructive breast surgery. Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2009.

Graf R, Biggs TM, Steely RL. Breast shape: a technique for better upper pole fullness. Aesth Plast Surg. 2000;24:348.

Lassus C. A technique for breast reduction. Int Surg. 1970;53:69.

Lassus C. Breast reduction: evolution of a technique – a single vertical scar. Aesth Plast Surg. 1987;11:107.

Lassus C. Update on vertical mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(7):2289-2298.

Lassus C. A 30-year experience with vertical mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:373.

Lejour M. Vertical mammaplasty and liposuction of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:100.

Lejour M. Vertical mammaplasty and liposuction of the breast. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing; 1994.

Lejour M. Vertical mammaplasty: update and appraisal of late results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(3):771-781.

Lejour M. Vertical mammaplasty: early complications after 250 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(3):764-770.

Lockwood T. Reduction mammaplasty and mastopexy with superficial fascial system suspension. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103(5):1411-1420.

Regnault B. Breast ptosis: definition and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 1976;3(2):193-203.

Rohrich RJ, Gosman AA, Brown SA, Reisch J. Mastopexy preferences: a survey of board-certified plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7):1631-1638.

Westreich M. Anthropomorphic breast measurement: protocol and results in 50 women with aesthetically perfect breasts and clinical application. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(2):468-479.