Superior Limbic Keratoconjunctivitis

Introduction

Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK) is a rare disorder of the superior cornea and conjunctiva, that was first fully described by Frederick Theodore in 1963.1 He suggested the term SLK to describe a series of patients with the following presenting signs: (1) inflammation of the superior tarsal conjunctiva, (2) inflammation of the superior bulbar conjunctiva, (3) fine punctate staining of the superior cornea, limbus, and the adjacent conjunctiva, and (4) filaments on the superior limbus or upper fourth of the cornea.

Presentation

Patients with SLK can present with a variety of non-specific complaints. The most common symptoms are irritation, burning, foreign body sensation, redness, photophobia, mucoid discharge from the eyes, and even an inflammatory ptosis. These symptoms are usually much more severe if the patient has corneal filaments. Often, the irritation is mild in the morning but worsens throughout the day.2 The symptoms can be vague and intermittent and often are mistaken for other ocular surface disease, such as dry eye and blepharitis. Due to the fact that the clinical findings are often missed because the superior conjunctival is frequently not examined, SLK patients can be misdiagnosed or not diagnosed for many years.

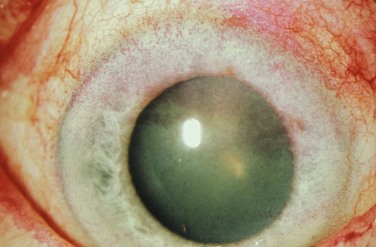

In untreated patients, the natural course of the disease is one of episodic relapses and gradual improvement over several years, with eventual resolution of symptoms. Most patients are affected bilaterally (Fig. 21.1), but asymmetric and unilateral disease occurs. The female to male ratio is variable but is roughly 2 : 1.3 Presentation typically occurs in the fourth or fifth decades of life.4 A familial association has rarely been reported but is not the norm.

Figure 21.1 Bilateral presentation of a patient with SLK.

Clinical Examination

The classic physical finding associated with SLK is superior bulbar conjunctival injection. Vital stains, such as rose bengal or lissamine green are the most effective way to highlight abnormal conjunctiva (Fig. 21.2). These stains are especially beneficial in cases where the conjunctival injection may be subtle. Caution should be taken though, as vital staining of the superior bulbar conjunctiva does not guarantee a diagnosis of SLK. Bainbridge et al. looked at 93 consecutive patients who presented to an eye clinic for any reason, that were subsequently stained with rose bengal. While none of them carried a diagnosis of SLK, 25% of them exhibited staining of the superior bulbar conjunctiva.2 This study reinforces the fact that a diagnosis of SLK should only be made after a thorough patient history is obtained and physical examination is performed. Other clinical findings of SLK include injection and redundancy of the superior bulbar conjunctiva, filaments of the superior cornea and conjunctiva, and a papillary reaction on the superior tarsal conjunctiva. The inferior tarsal conjunctiva is typically normal. Corneal hypoesthesia is also sometimes present.1 The presence of filaments on the superior cornea should alert the clinician to the diagnosis of SLK, as this is the most common cause of this finding. When evaluating a patient for SLK, the upper lid should be everted to look for the common papillary reaction that is often seen in this condition. Key to the diagnosis of SLK is the willingness of the clinician to examine the superior bulbar conjunctiva. Many clinicians do not elevate the upper lid to examine the superior part of the eye. If the upper lid is not elevated, the diagnosis of SLK is missed. It is prudent to include lid elevation as part of the examination steps in any patient with ocular surface symptoms. Another factor in missing the diagnosis of SLK, is the fact that the superior bulbar conjunctival injection may be subtle. If the clinician looks at the superior conjunctiva with the biomicroscope on high magnification only, subtle findings may be unrecognized. It is useful in the SLK patient to simultaneously elevate both upper lids and look at the superior conjunctiva with the unaided eye. This simple technique may often be the most useful way to see the conjunctival injection.

Etiology

Abnormalities in the interaction of the superior tarsal and bulbar conjunctiva lead to constant abnormal movement of the superior bulbar conjunctiva during blinking. This abnormality could be due to tight apposition of the tarsal conjunctiva against the globe in the setting of thyroid eye disease, exophthalmos, scarring of the superior tarsal conjunctiva,5 inflammation, or dryness. This theory is supported by the strong association of SLK with both thyroid dysfunction, which is found in 33% of patients suffering from SLK, and dry eye disease, which is found in 25% of patients diagnosed with SLK.3 Further credence is given to the mechanical theory by the discovery that transforming growth factor-beta2 and tenascin are up-regulated in the conjunctiva of patients with SLK, as compared to controls. Expression of both of these is known to be affected by mechanical stress and injury.6

Other biochemical abnormalities have been identified in patients with SLK. For example, expression of certain cytokeratins (CKs) has been found to be altered when compared to controls. Decreased expression of a marker for nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium, CK13, has been noted, along with increased expression of CK14. Also, increased expression of CK10, a marker for keratinization, has been positively correlated with disease severity.7 These results suggest that an abnormality of differentiation in the conjunctival epithelium plays a role in the disease. In other studies, an overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases 1 and 3 (MMP-1 and MMP-3) has been noted, but it is unclear exactly what role this plays in the pathogenesis of the disease.8

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of SLK is based primarily on the clinical findings described earlier. The redundancy of the superior bulbar conjunctiva can be demonstrated by using a cotton-tipped applicator to pull the conjunctiva down over the superior cornea. This should be done after application of topical anesthesia and is not possible with normal conjunctiva. Impression cytology may give additional certainty to the diagnosis but is rarely necessary. With impression cytology, impressions of the superior bulbar conjunctiva demonstrate severe squamous metaplasia, with an absence of goblet cells. Impressions of the superior tarsal conjunctiva show mild squamous metaplasia with many inflammatory cells, while impressions of the inferior tarsal conjunctiva are essentially normal.9

Confocal microscopy has recently been investigated as an adjunctive diagnostic tool when SLK is suspected clinically. Two variables that were studied were mean individual epithelial cell area (MIECA) and nucleocytoplasmic (N/C) ratio. As compared to normal controls, SLK patients were found to have a significantly increased MIECA and a decreased N/C ratio. Additionally, the inflammatory cell density in SLK patients was increased, compared to controls. This increase significantly correlated with superior bulbar conjunctival rose bengal scores, as measured by impression cytology, giving additional credence to confocal microscopy as a reliable diagnostic tool.10

Treatment

Over the past several decades, a variety of treatments for SLK have been explored with varying reports of success. Initially, topical medical treatments should be attempted. Aggressive lubrication of the ocular surface should be used, either alone or in conjunction with punctal occlusion. Autologous serum tears may be more beneficial than commercial artificial tears, providing objective and subjective improvement in 82% of cases.11 Topical steroids are often used, and have resulted in symptomatic improvement in some cases, but the overall results have been variable. Topical cyclosporine A, used four times daily has had very good success, with symptom resolution in 100% of patients in one report.12 Topical ketotifen fumarate has also met with promising success in symptom resolution, though objective signs have not always improved.13 In addition, topical administration of vitamin A and mast cell stabilizers has led to symptom resolution in a high percentage of patients.14,15

If topical treatments are unsuccessful, injection of medication may be indicated. In one study, a supratarsal triamcinolone injection was found to decrease symptoms, as well as corneal and conjunctival staining in all patients who received the treatment.16

Chun and Kim used large-diameter contact lenses to decrease trauma to the superior bulbar conjunctiva, which resulted in improvement of symptoms in 38% of patients. Those SLK patients who did not improve were given an injection of botulinum toxin A to the pretarsal orbicularis muscle. This resulted in resolution of symptoms in 100% of patients.4

Surgical Treatment

As the hallmark of SLK is redundancy of the superior bulbar conjunctiva, the surgical treatments target that structural abnormality. Many different methods have been employed to attempt to tighten the redundant superior bulbar conjunctiva. Initial attempts using silver nitrate were effective, but caution needs to be taken as severe ocular burns can result, especially when using a solid applicator.17 In fact, a solid silver nitrate application should never be utilized in the management of SLK. Some clinicians have advocated the use of thermocautery to tighten the superior bulbar conjunctiva. Udell et al. found that this led to symptom resolution in 73% of patients, in addition to an increase in the density of goblet cells after resolution.18 Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, using the double freeze–thaw technique, was found to resolve symptoms in 57% of eyes after one treatment and 100% of eyes after one repeat treatment.19 Conjunctival fixation sutures placed in the superior fornix, have been reported to result in complete symptom resolution as well.20

References

1. Theodore, FH. Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Eye Ear Nose Throat Mon. 1963;42:25–28.

2. Bainbridge, JW, Mackie, IA, Mackie, I. Diagnosis of Theodore’s superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Eye (Lond). 1998;12(Pt 4):748–749.

3. Nelson, JD. Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis (SLK). Eye (Lond). 1989;3(Pt 2):180–189.

4. Chun, YS, Kim, JC. Treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis with a large-diameter contact lens and botulium toxin A. Cornea. 2009;28:752–758.

5. Raber, IM. Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis in association with scarring of the superior tarsal conjunctiva. Cornea. 1996;15:312–316.

6. Matsuda, A, Tagawa, Y, Matsuda, H. TGF-beta2, tenascin, and integrin beta1 expression in superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1999;43:251–256.

7. Matsuda, A, Tagawa, Y, Matsuda, H. Cytokeratin and proliferative cell nuclear antigen expression in superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Curr Eye Res. 1996;15:1033–1038.

8. Sun, YC, Hsiao, CH, Chen, WL, et al. Overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) and MMP-3 in superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3701–3705.

9. Gris, O. Conjunctival resection with and without amniotic membrane graft for the treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2010;29:1025–1030.

10. Kojima, T, Matsumoto, Y, Ibrahim, OM, et al. In vivo evaluation of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis using laser scanning confocal microscopy and conjunctival impression cytology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:3986–3992.

11. Goto, E, Shimmura, S, Shimazaki, J, et al. Treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis by application of autologous serum. Cornea. 2001;20:807–810.

12. Sahin, A, Bozkurt, B, Irkec, M. Topical cyclosporine a in the treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis: a long-term follow-up. Cornea. 2008;27:193–195.

13. Udell, IJ, Guidera, AC, Madani-Becker, J. Ketotifen fumarate treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2002;21:778–780.

14. Confino, J, Brown, SI. Treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis with topical cromolyn sodium. Ann Ophthalmol. 1987;19:129–131.

15. Ohashi, Y, Watanabe, H, Kinoshita, S, et al. Vitamin A eyedrops for superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;105:523–527.

16. Shen, YC, Wang, CY, Tsai, HY, et al. Supratarsal triamcinolone injection in the treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2007;26:423–426.

17. Laughrea, PA, Arentsen, JJ, Laibson, PR. Iatrogenic ocular silver nitrate burn. Cornea. 1985–1986;4:47–50.

18. Udell, IJ, Kenyon, KR, Sawa, M, et al. Treatment of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis by thermocauterization of the superior bulbar conjunctiva. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:162–166.

19. Fraunfelder, FW. Liquid nitrogen cryotherapy of superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:234–238.

20. Yamada, M, Hatou, S, Mochizuki, H. Conjunctival fixation sutures for refractory superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:1570–1571.