CHAPTER 20 Superior and Medial Pedicle Breast Reduction Using a Vertical Pattern

Summary/Key Points

Introduction

The major advantage of vertical scar reduction mammaplasty is the improved long-term projection of the breasts following this procedure. With vertical scar reduction mammaplasty, the inferior wedge resection of the redundant breast tissue that contributed to breast ptosis and the subsequent suturing of the medial and lateral pillars, results in coning of the breast and a narrower, more projecting breast, which is the hallmark of this procedure.1

Lassus2,3 and Lejour4 are responsible for much of the pioneering work on vertical scar reduction mammaplasty. In 1969, Lassus2,3 developed a technique using a superior dermoglandular pedicle for transposition of the nipple–areola complex; a central en bloc excision of skin, fat, and gland; and a vertical scar to finish. The shape of the breast was produced by reapproximating the medial and lateral pillars with only suturing of the skin. In 1994, Lejour4 described a modification of Lassus’ technique in which liposuction was used pre-excision to eliminate fat contributing to breast volume; the skin surrounding the excised area was undermined; the superior dermoglandular pedicle was sutured to the pectoralis fascia; sutures were used in the breast parenchyma to reapproximate the pillars producing a more durable breast shape. Gathering of the skin of the vertical wound was used to keep the scar above the inframammary crease. In 1999, Hall-Findlay5,6 described a modification of Lejour’s technique using a mosque dome skin marking pattern; a full-thickness medial dermoglandular pedicle to transpose the nipple–areola complex; no skin undermining; no suturing of the pedicle to the pectoralis fascia; and liposuction only rarely to reduce breast volume. Hall-Findlay’s technique has since become the most commonly performed limited incision breast reduction technique as reflected in a 2002 American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery survey of board-certified plastic surgeons.7

In 2006, we described our technique for vertical scar reduction mammaplasty that uses a mosque dome skin marking pattern; transposition of the nipple–areola complex on a superior or medial dermoglandular pedicle, depending on its position with respect to the skin markings; an en bloc excision of skin, fat, and gland; postexcision liposuction; and wound closure in two planes, including parenchymal pillar sutures and gathering of the skin of the vertical wound using four-point box stitches.1 Since 1989, we have performed this technique on over 2000 patients requiring breast reduction resulting in consistently good breast shape while leaving less scarring than more commonly performed breast reduction techniques.

Since Manchot’s8 1889 description of the blood supply to the breast, there have been many varying descriptions in the literature. Recently, van Deventer9 performed anatomical studies on 15 female cadavers in an attempt to further clarify the blood supply to the nipple–areola complex and found a large variation in the pattern of its blood supply. In all breasts, the nipple–areola complex received a blood supply medially or superiorly from one or more perforating arteries from the superior four perforating branches of the internal thoracic artery. The third perforator most frequently contributed blood supply to the nipple–areola complex in 47.5% of breasts, while the second perforator contributed in 25%, the first perforator in 15% and the fourth perforator in 12.5%. In 13 of 27 breasts, the nipple–areola complex did not receive any blood supply from superiorly. In 16 of 27 breasts, the nipple–areola complex received blood supply inferiorly from the fourth, fifth or sixth anterior intercostal arteries, with branches from the fourth anterior intercostal artery being the most common, occurring in 68.8% of breasts. The lateral thoracic artery contributed blood supply to the nipple–areola complex in 16 of 27 breasts, while the posterior intercostal arteries supplied the nipple–areola complex in only 1 of 27 breasts. In 2 of 27 breasts, the nipple–areola complex received blood supply from direct branches of the axillary artery. There were abundant anastomoses between these blood supplies around the nipple–areola complex. From this study, van Deventer et al10 concluded that the nipple–areola complex generally has a dual blood supply with the internal thoracic-anterior intercostal artery system providing blood supply from medioinferiorly and the lateral thoracic artery and other minor contributors providing blood supply from laterosuperiorly, with the most reliable source of blood supply arising from the internal thoracic artery.

Patient Selection

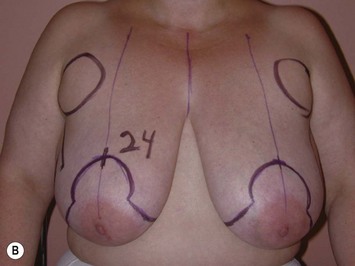

We have performed vertical scar reduction mammaplasty exclusively on over 2000 patients presenting for breast reduction (Fig. 20.1). In 2006, we performed a chart review of 250 consecutive patients treated between November of 2000 and December of 2003.1 In this clinical series, the average age of the patients was 38.5 years (range, 15 to 76 years) and the average body mass index was 28.8 kg/m2 (range, 17.3 to 46.3 kg/m2). The average weight of tissue excised per breast was 526 g (range, 10 to 2020 g). Liposuction was performed in 78.4% of cases and the average volume liposuctioned per breast was 140 ml (range, 50 to 500 ml). The average total reduction per breast (including liposuction when performed) was 636 g (range, 60 to 2020 g).

In addition, complications were analyzed based on body mass index, amount of reduction, pedicle selection, and use of liposuction.1 Although there was no statistically significant difference in the rate of complications between groups for amount of reduction, pedicle selection, and use of liposuction, there was a statistically significant difference between groups for body mass index with complications occurring less frequently in patients of normal weight (body mass index, 20.5 to 25.0 kg/m2). Since this study was published, we have limited performing this procedure to patients with a body mass index less than 35 kg/m2. Patients presenting for breast reduction with a body mass index greater than 35 kg/m2 are advised to lose weight prior to undergoing this procedure to decrease their risk for complications including superficial wound dehiscence and fat necrosis.

Along with other authors,3,5 we recommend learning this technique by initially operating on patients with mild to moderate hypertrophy and good skin quality. After becoming more familiar with the technique, one can progress to performing the technique on patients with more severe hypertrophy and poorer skin quality. Although it is possible to perform this technique on patients with extremely large breasts, it is important to realize that their postoperative breast size will likely remain larger when compared to other techniques because of the amount of skin preserved with a vertical scar reduction. In patients with severe mammary hypertrophy desiring a very small postoperative breast size, this technique is not suitable.

Indications

In an effort to establish clear, practical, objective, and fair criteria that could be applied by physicians to help differentiate women seeking breast reduction primarily for symptom relief versus aesthetic improvement, Kerrigan et al11 reported an evidence-based objective definition of medical necessity for breast reduction. Seven symptoms specific to breast hypertrophy were identified including: upper back pain, rashes, bra strap grooves, neck pain, shoulder pain, numbness, and arm pain. Results of this study established that women reporting at least two of seven physical symptoms all or most of the time improved to a significantly greater extent than women reporting less than two symptoms all or most of the time. Their data suggested that women reporting at least one of seven physical symptoms may also report greater improvement than those with no symptoms all or most of the time. We have found this definition of medical necessity useful in evaluating patients that will benefit most from breast reduction by reduction of their symptoms associated with mammary hypertrophy.

Operative Technique

Skin markings

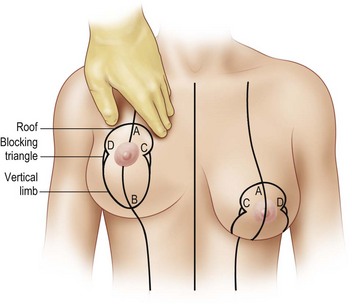

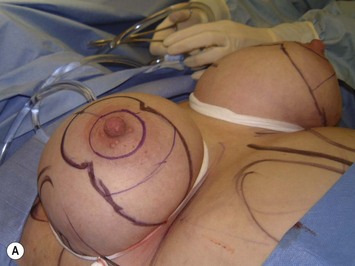

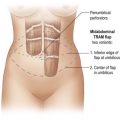

A summary of the operative technique is given in Box 20.1.With the patient in the sitting position, the midline of the chest and the inframammary creases are marked (Fig. 20.2). The central axis of the breast is drawn by extending a straight line from the midpoint of the clavicle through the nipple to intersect with the inframammary crease. One hand is inserted behind the breast to the level of the inframammary crease, and this point is projected anteriorly onto the breast and marked (A). This point will be the new location of the superior border of the areola. The planned postoperative position of the nipple–areola complex in this technique is approximately 2 cm lower than it would be using an inverted-T scar/inferior pedicle breast reduction technique because compared with preoperative skin markings, the nipple–areola complex is located significantly higher at both early and long-term follow-up after this procedure (Fig. 20.3).12 The inferior limit of the skin excision is marked (B) 2 to 4 cm above the inframammary crease, depending on the size of the reduction. This distance is shorter in smaller reductions and longer in larger reductions. The inframammary crease moves up after vertical scar breast reduction techniques and this phenomenon accounts for the vertical scar extending onto the chest wall in earlier vertical scar techniques. Limiting the inferior end of the vertical scar to a point above the inframammary crease prevents this problem. A mosque dome pattern is marked onto the breast. The roof of the mosque dome pattern is constructed by extending curved lines from point A to points C and D to form the border of the new nipple–areola complex. The roof is drawn so that when points C and D are brought together, it will form a circle. The vertical limbs of the mosque dome pattern are constructed by extending curved lines from point B to points C and D to form the margins of the skin to be excised. The inferior extent of the skin resection is marked in the shape of a ‘V’ instead of a ‘U’ as described in other techniques.5,13 We feel that this allows for easier skin closure. Blocking triangles are drawn from point C and point D, toward the central axis of the breast, to prevent the formation of the teardrop deformity of the areola.

Box 20.1 Summary of operative technique

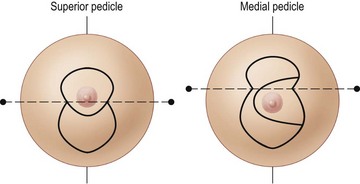

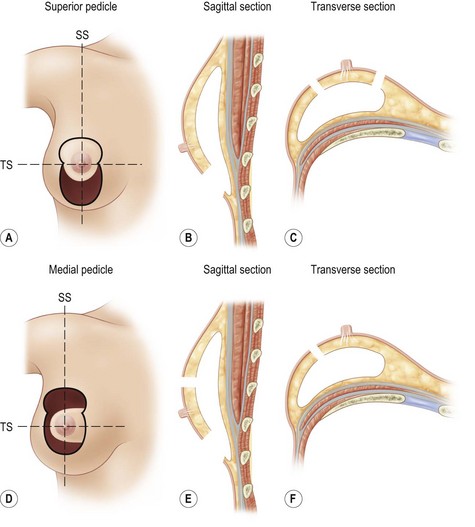

The skin in the axillary area and along the lateral chest wall is marked denoting the areas to be liposuctioned. After the patient has been anesthetized and placed in the supine position, a tourniquet is applied to the breast to keep the skin taut. The nipple–areola complex is outlined using a metal washer, 4.5 cm in diameter, centered over the nipple. At this point in the operation, we select the type of pedicle to be used to transpose the nipple–areola complex (Fig. 20.4). If any part of the new areola lies superior to a line joining the blocking triangles, a superior dermoglandular pedicle is used; if all of the areola lies inferior to this line, a medial dermoglandular pedicle is used. This rule limits pedicle length and avoids vascular compromise of the nipple–areola complex. The superior pedicle is drawn from the blocking triangles inferiorly, leaving a 2.5 cm border around the nipple–areola complex. The medial pedicle can be drawn with a base that is partially in the roof and in the vertical limb or completely in the vertical limb of the mosque dome, depending on the location of the nipple–areola complex. A 2.5 cm border is left around the nipple–areola complex. The base of the medial pedicle should be wide enough to maintain a pedicle width-to-length ratio of no less than 1 : 2 to preserve its blood supply but should be narrow enough to allow easy insetting of the nipple–areola complex.

Breast shaping and wound closure

Wound closure is performed in two planes, including parenchymal pillar sutures and gathering of the skin of the vertical wound using box stitches. Inverted 1-0 Vicryl sutures (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ) placed through the superficial fascial system are used to reapproximate the medial and lateral pillars of the breast parenchyma. These parenchymal pillar sutures may contribute to improved long-term projection of the breasts following this procedure preventing pseudoptosis or ‘bottoming out’ of the breast.5 Usually, two parenchymal pillar sutures are used, but the inferiormost suture should be placed no closer than 4 cm from the inferior end of the incision. Placing the pillar sutures too close to the inferior end of the vertical wound may lead to the formation of a dog-ear. Temporary skin staples are used to close the vertical wound while suturing the skin. All suturing of the skin is performed using a 4-0 Monocryl suture (Ethicon). A four-point box stitch is used to gather the skin of the vertical wound. Use of this box stitch allows selective gathering of the vertical wound leading to more control of the vertical scar. The skin is gathered beginning at the inframammary crease. Gathering of the skin assists in eliminating dog-ears close to the inferior end of the vertical scar. Skin within 1 cm of the areola is not gathered to prevent distortion of the areola. After gathering of the skin, any gaping of the horizontal pleats caused by the box stitches along the vertical wound is corrected using a deep dermal, inverted suture. Correction of horizontal pleats is essential because they do not settle with time and lead to small horizontal scars within the larger vertical scar. The box stitch successfully shortens the length of the vertical wound. Skin staples are used along the vertical wound for final closure. Deep dermal, inverted sutures are used to inset the nipple–areola complex. Intradermal, continuous sutures are used for closer approximation of skin edges of the periareolar wound.

Pitfalls and How to Correct

Case 1: Selection of superior or medial pedicle

The fact that necrosis of the nipple–areola complex has never occurred in more than 2000 cases performed using this technique is related to our pedicle choice and design. Early in our series, we used a superior pedicle to transpose the nipple–areola complex as described by Lassus2 and Lejour.4 After encountering difficulty with long pedicles that required excessive thinning and folding to allow for insetting, we began using a medial pedicle in cases of mammary hypertrophy with greater degrees of ptosis. By using either a superior or medial pedicle to transpose the nipple–areola complex depending on its position with respect to the mosque dome skin marking pattern, pedicle length is limited avoiding vascular compromise of the nipple–areola complex. We developed a very common-sense and practical approach for pedicle selection in each patient,12 using a superior pedicle if any part of the new areola lies superior to a line joining the blocking triangles, and a medial pedicle if all of the areola lies inferior to this line (Fig. 20.5). Lassus3 also restricted the use of the superior pedicle to cases in which the nipple–areola complex was transposed no more than 10 cm and used a lateral pedicle when transposition was greater than 10 cm.

Using a full-thickness pedicle is unnecessary to preserve blood supply to the nipple–areola complex and can result in difficulty with insetting the pedicle.13 In this technique, we excise breast tissue deep to the pedicle but keep the pedicle 2.5 cm thick which adequately preserves the blood and nerve supply. In addition, this allows the pedicle to be easily inset. A border of at least 2.5 cm of breast tissue surrounding the nipple–areola complex also helps to prevent necrosis of the nipple–areola complex.

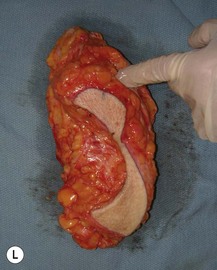

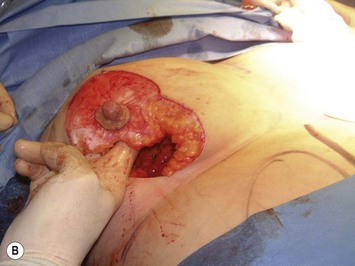

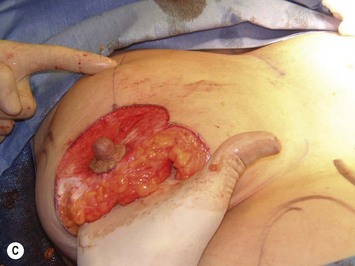

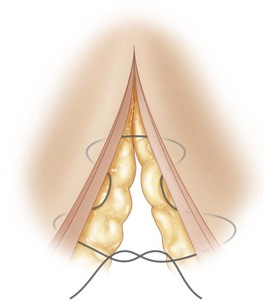

Case 2: Surgical excision and design of parenchymal pillars

The inferior wedge resection of the redundant breast tissue that contributed to breast ptosis allows for the creation of medial and lateral parenchymal pillars. Suturing of these parenchymal pillars results in coning of the breast and is responsible for the pleasing projection associated with this technique. In this technique, it is very important to keep the flaps 2.5 cm thick throughout their length when excising breast tissue lateral to the anterior axillary line and superiorly to the clavicle (Fig. 20.6). Hall-Findlay6 describes beginning the excision with a flap thickness of 5 mm at the edge of the vertical wound and then ‘beveling out’ so that the flaps become progressively thicker at the periphery, but this does not apply to our technique. With this technique, if the flaps are not kept 2.5 cm thick throughout their length, a concave deformity of the inferior pole of the breast can occur.

Case 3: Gathering skin of vertical wound using box stitches

A four-point box stitch is used to gather the skin of the vertical wound (Fig. 20.7). Use of this box stitch allows selective gathering of the vertical wound leading to more control of the vertical scar and eliminating dog-ears close to the inferior end of the vertical scar. The box stitch successfully shortens the length of the vertical wound with an average early postoperative length of the inframammary crease to inferior border of the nipple–areola complex distance of 10.3 cm and range from 6.5 to 14 cm.12 As opposed to inverted-T scar/inferior pedicle breast reductions that are prone to the occurrence of pseudoptosis, a longer vertical scar is acceptable in vertical scar/superior or medial pedicle breast reductions because pseudoptosis does not occur after this technique and thus the vertical scar does not lengthen over time.12 In addition, Lassus2 measured the distance between the inferior border of the areola and the inframammary crease in young women with beautiful breasts and found measurements ranging from 4.5 to 10 cm and concluded that the distance was dependent on the size of the breast. Hall-Findlay5 showed results where this distance was up to 12 cm. Although other authors4,5 have previously described using a continuous intradermal suture to gather the skin of the vertical wound, it may be a source of wound healing problems because of constriction of the blood supply to the skin edges (Fig. 20.8).13 We feel that the box stitch gathers the skin of the vertical wound effectively while causing less ischemia to the skin edges.

1 Lista F, Ahmad J. Vertical scar reduction mammaplasty: 15-year experience including a review of 250 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:2152-2165.

2 Lassus C. A 30-year experience with vertical mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:373-380.

3 Lassus C. Update on vertical mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:2289-2298.

4 Lejour M. Vertical mammaplasty and liposuction of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:100-114.

5 Hall-Findlay EJ. A simplified vertical reduction mammaplasty: Shortening the learning curve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:748-759.

6 Hall-Findlay EJ. Pedicles in vertical breast reduction and mastopexy. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29:379-391.

7 Rohrich RJ, Gosman AA, Brown SA, Tonadapu P, Foster B. Current preferences for breast reduction techniques: a survey of board-certified plastic surgeons 2002. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1724-1733.

8 Manchot C. Die hautarterien des menschlichen korpers. Leipzig: Vogel; 1889.

9 van Deventer PV. The blood supply of the nipple–areola complex of the human mammary gland. Aesth Plast Surg. 2004;27:393-398.

10 van Deventer PV, Page BJ, Graewe FR. The safety of pedicles in breast reduction and mastopexy procedures. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:307-312.

11 Kerrigan CL, Collins ED, Kim HM, et al. Reduction mammaplasty: defining medical necessity. Medical Decision Making: Int J Soc Medical Decision Making. 2002;22:208-217.

12 Ahmad J, Lista F. Vertical scar reduction mammaplasty: The fate of nipple–areola complex position and inferior pole length. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:284-291.

13 Hall-Findlay EJ. Discussion: Vertical scar reduction mammaplasty: 15-year experience including a review of 250 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:2166-2169.