CHAPTER 20 Substance use disorders

This chapter is concerned with problems arising from the use of alcohol, tobacco, illicit substances or prescribed medications that are taken for non-medical purposes.

Substances of abuse

Alcohol affects the release of dopamine, noradrenaline and endogenous opioids, producing an activated state that is pleasurable. It specifically acts at the gamma-aminobatyric acid type A (GABA-A) receptor, thus accounting for its anxiolytic properties. At higher concentrations, alcohol also blocks glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, resulting in amnesia and cerebral depressant effects (see Table 20.1). Ten grams of alcohol per hour will cause an increase in blood alcohol concentration levels to between 0.01% and 0.02%, with lower concentrations possible where there is marked tolerance, and higher concentrations found in females of small stature. Hazardous intake by young people tends to lead to harm as a result of behaviours associated with acute intoxication (e.g. motor vehicle accidents, assaults, drownings and suicides). Older people experience the sequelae of long-term hazardous use, such as medical complications.

| Blood alcohol concentration (grams of alcohol per 100 ml of blood)∗ | Effects |

|---|---|

| 0.02–0.05 | Cheerful, relaxed, reduced inhibitions, and coordination and judgment beginning to be affected |

| 0.06–0.10 | Speech louder, very talkative, feels self-confident, less cautious, slowed reaction time and impaired coordination |

| 0.20 | Sedated rather than active, clumsy, slurred speech, impaired cognitive functioning and amnesia |

| 0.30–0.40 | Semiconscious or unconscious, bodily functions beginning to deteriorate, and fatalities can occur |

| 0.50 | Fatalities common |

Amphetamines are a group of synthetic drugs that include ‘speed’ (amphetamine sulphate, dexamphetamine), ‘meth’ (methamphetamine or methylamphetamine) and ‘crystal meth’ (methamphetamine hydrochloride). They come in many forms (e.g. crystalline, paste, powder and pills) and in varying strengths. They are generally ingested or injected, although they can be snorted or smoked depending on what preparation they are in. They produce their stimulating effects through releasing dopamine and noradrenaline from pre-synaptic nerve terminals. Intoxication is associated with euphoria, increased physical activity, confidence, stamina and reduced need for sleep. Use that is greater than twice per week is more likely in dependent individuals. Dependence is also more likely among those who inject (50% likelihood). Long-term risks include those resulting from injecting if this is the mode of use. Teeth grinding, appetite suppression and weight loss, headache, chronic psychosis, mood instability, unpredictable behaviour and violence may also occur.

Benzodiazepines act on GABA-A receptors, resulting in anxiolytic, hypnotic, sedative and anticonvulsant effects. The duration of effects varies according to the half-life of the benzodiazepine consumed. Abuse as a component of polysubstance abuse, dependence in conjunction with alcohol or other drug dependence, and long-term dependence in the context of longstanding repeat prescriptions are the commonest problematic patterns of use. Dependence can follow 3 months of regular use, and in some instances has been noted to occur much earlier, particularly if there is already dependence on a sedating substance. Sleep impairment, sedation, cognitive impairment and falls in the elderly are some of the problems associated with dependence.

Hallucinogens include a variety of substances, such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), phenylalkylamines (mescaline) and psilocybin (from mushrooms). The effects are highly variable depending on the user, the expectations of the user and the situation in which it is taken. The central experiences of intoxication are perceptual distortions and hallucinations, as well as depersonalisation and derealisation. Synesthesias may occur. Mood effects vary and anxiety can be prominent, reaching panic. Delusions and agitation can occur. Tolerance arises, but withdrawal syndromes have not been described. Most use is intermittent. Flashbacks are distressing perceptual disturbances reminiscent of intoxication which recur in the absence of continued use.

Caffeine is the most widely used substance in our community. A typical 150 mL cup of brewed coffee contains 100–150 mg of caffeine, instant coffee contains 30–100 mg of caffeine, and tea contains 30–100 mg of caffeine. Symptoms of toxicity include anxiety, insomnia, nausea and abdominal discomfort, diuresis, and elevated blood pressure and heart rate. These symptoms occur at doses above 500 mg, or more if tolerant. Dependence is common and withdrawal symptoms are most commonly headache and cognitive slowing.

Prevalence and costs

Epidemiological surveys consistently show that most people who report using substances do not do so on a regular basis (see Table 20.2). Experimental use is more common among adolescents and young people, while more frequent use is more prevalent in the 20–29-year-old age group. However, individuals with substance use disorders who present for treatment are typically older. While single episodes of use can cause problems (e.g. driving while intoxicated), individuals who use more frequently are more likely to experience deleterious mental and physical health consequences. Indeed, substance use and mental disorders frequently co-occur, and such comorbidity substantially impacts upon treatment outcomes for both conditions.

TABLE 20.2 Lifetime and recent (last 12 months) use of substances in Australia in those 14 years and over

| Substance | % population ever using substance | % population using substance in the last 12 months |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 89.9 | 82.9 |

| Cannabis | 33.5 | 9.1 |

| Ecstasy | 8.9 | 3.5 |

| Hallucinogens | 6.7 | 0.6 |

| Methamphetamine | 6.3 | 2.3 |

| Cocaine | 5.9 | 1.6 |

| Heroin | 1.6 | 0.2 |

Source: National Drug Strategy, Household Survey 2008.

Substance use and misuse are important contributors to workplace injury, loss of productivity, relationship breakdowns, violence and crime, as well as illness and disease. The cost to our society is enormous, estimated in the tens of billions of dollars, with licit drugs accounting for the bulk of the costs (56% tobacco, 27% alcohol, 15% illicit drugs). Such figures are startling, and highlight the importance of early detection and treatment.

Patterns of use

An individual’s pattern of substance use can range from experimental, through social/recreational to problem use (i.e. a substance use disorder). It is important to consider this pattern of use in addition to the quantity of substance consumed. The terms abuse and dependence are used to describe patterns of problem use (see Table 20.3); dependence is generally regarded as the more reliable, robust and useful construct.

TABLE 20.3 DSM–IVTR criteria for abuse and dependence (synopsis)

| Substance abuse | Substance dependence |

|---|---|

| Maladaptive pattern of use in a 12-month period | Maladaptive pattern of use in a 12-month period |

| Impairment or distress | Impairment or distress |

| More than one of: |

Screening and assessment

The CAGE questionnaire. This screener consists of four questions, and scoring positive for two items is highly indicative of dependence on alcohol. The four questions are:

The CAGE questionnaire. This screener consists of four questions, and scoring positive for two items is highly indicative of dependence on alcohol. The four questions are:

Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT). This quick, ten-item questionnaire is good at identifying risky levels of alcohol use, as well as the severity of alcohol dependence.

Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT). This quick, ten-item questionnaire is good at identifying risky levels of alcohol use, as well as the severity of alcohol dependence. Alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST). This questionnaire measures the frequency of substance use (lifetime and 3-month) across nine drug categories. There is also a brief intervention package associated with the screener that is freely available from the WHO website.

Alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST). This questionnaire measures the frequency of substance use (lifetime and 3-month) across nine drug categories. There is also a brief intervention package associated with the screener that is freely available from the WHO website.History

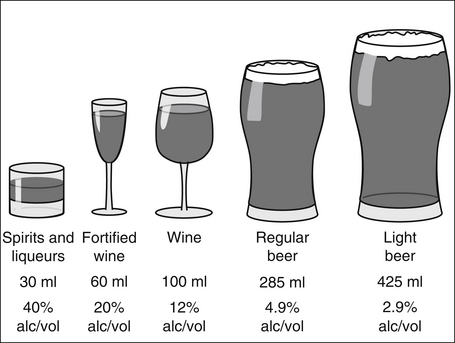

When assessing for substance use, a non-judgmental approach during history taking is imperative so as to avoid defensive answers. Alcohol should be quantified as the number of standard drinks (1 standard drink contains 10 g of alcohol), and all alcoholic beverages in Australia must now have this displayed on the label (see Figure 20.1). It is useful to understand the local street terms for available substances (e.g. ‘ice’, ‘whiz’ or ‘goey’ referring to methamphetamines), and to know the quantities by which it is consumed or purchased. For example, methamphetamine is often sold as ‘points’ (very loosely equating to 0.1 g). There is enormous variation in the purity of illicit substances, so the cost may be the best way to define the amount of substance being consumed.

The patient should be asked about use of all drugs of abuse in a systematic manner (see Box 20.1). Use of more than one substance to problematic levels should be expected, as polydrug use is common. It is particularly important to ask when the substance was last used, as this will often help identify current issues that the patient is presenting with (e.g. problems related to intoxication or withdrawal). Features of intoxication vary depending on the substance consumed, and clinicians need to familiarise themselves with these effects (see below). Such information also assists in the assessment of abnormal mental states, particularly if there is a history of a coexisting mental disorder.

As with many areas of psychiatry, obtaining history from other sources can lead to a greater understanding of the extent of substance use, the effects of intoxication, as well as associated problems. Many people have difficulty recalling their intake spontaneously. It is often helpful to ask them to recount what they have consumed over the past week, working backwards on a daily basis, from yesterday to 1 week ago. You should establish whether the amount consumed was typical for them, and, if not, how it varied from their usual intake.

Mental state examination

Features to look for depend on the substance used, but can include:

Physical examination

Investigations

full blood count and liver function tests (about 75% of people with raised mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) are likely to have an alcohol disorder)

full blood count and liver function tests (about 75% of people with raised mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) are likely to have an alcohol disorder) screening for viral hepatitis antigens and antibodies, and for HIV (consent should be obtained for these investigations)

screening for viral hepatitis antigens and antibodies, and for HIV (consent should be obtained for these investigations)Substance-induced disorders

This important concept is defined in DSM–IVTR as:

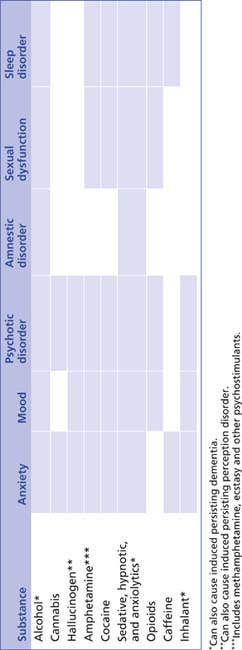

It is important to note that heavy use of psychoactive substances can mimic the symptoms of almost any mental disorder, and should be considered a differential diagnosis for most presentations. Table 20.4 shows the range of disorders that can be induced by psychoactive substance use. In addition to induced disorders, many substances can cause symptoms, but not enough to justify a full diagnosis.

Management

Treatment options

Motivational enhancement is a useful therapeutic strategy for patients with a substance use problem, and can be used throughout treatment. It is helpful to use the stages of change approach to map where the patient is, and focus your therapeutic approaches accordingly (see Table 20.5). However, it is important to note that such stages are relatively fluid, and can change rapidly depending on psychosocial circumstances (e.g. break-up of a relationship or resolution of crisis).

TABLE 20.5 Stages of change and motivational enhancement techniques

| Conceptual stage | Description | Consider approach |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-contemplation | The individual is not thinking about change | Provide factual information about the effects of substance use. Avoid confrontation. Encourage considering change, offering an optimistic perspective |

| Contemplation | The individual is thinking about change within the next 6 months | Examine with the patient the pros and cons of change, as well as continuing intake. Consider the compatibility of these with their broader life and health goals. Acknowledge ambivalence |

| Action | The individual has commenced attempts to change their use | Assist patient to enact strategies to change pattern of use |

| Maintenance | The individual has made a change | Assist patient to address ongoing ambivalence, rehearse relapse-prevention strategies and develop new skills |

| Relapse | The individual returns to aspects of previous behaviour (not always a full relapse) | Support the patient and assist them to reengage with treatment as above |

Co-occurring mental health disorders must also be considered. Substance use and mental disorders commonly co-occur, and integrated treatment should be offered for both conditions. This ensures that the patient understands the link between their substance use and mental disorder, and that common issues underpinning both disorders are addressed simultaneously.

Withdrawal management

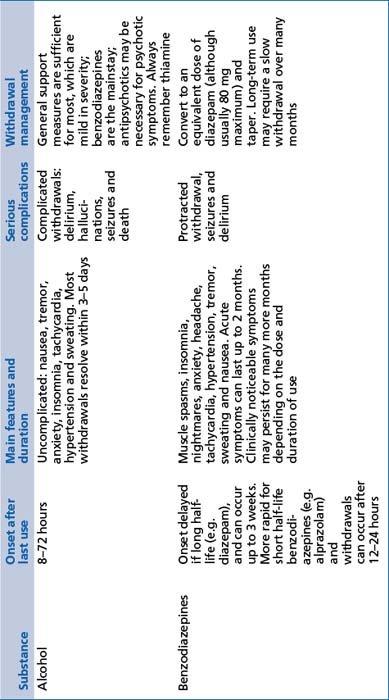

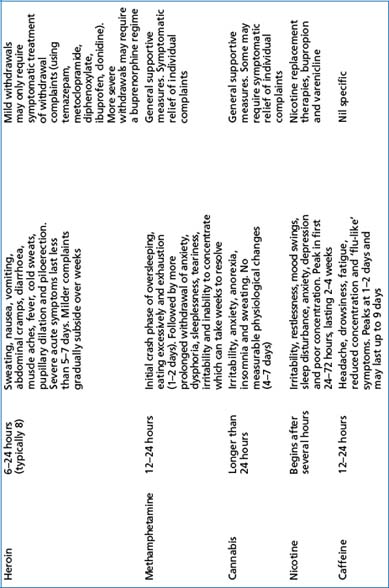

The supervised management of withdrawal states is often referred to as ‘detox’ (detoxification), and should not be considered the main focus of treatment. In fact, only a very small percentage of patients subsequently remain substance free in the long term or are able to continue to use in a controlled fashion. Nevertheless, detoxification may be a starting point for change, and other treatment strategies (see below) should also be offered. Stimulant-like substances (e.g. methamphetamines) produce withdrawal states characterised by lethargy and dysphoria. Sedative substances (e.g. alcohol and opioids) produce withdrawal effects of overactivation, such as anxiety and autonomic arousal (see Table 20.6).

Psychological strategies

Brief intervention. This approach is effective for non-dependent levels of use. It involves feedback to the patient about their consumption levels in relation to known safe levels of use; specific advice about how to change and achieve goals; encouragement, emphasising self-efficacy; and an optimistic perspective.

Brief intervention. This approach is effective for non-dependent levels of use. It involves feedback to the patient about their consumption levels in relation to known safe levels of use; specific advice about how to change and achieve goals; encouragement, emphasising self-efficacy; and an optimistic perspective. Motivational enhancement. This is a therapeutic approach that avoids confrontation, acknowledges and examines ambivalence, and assists the patient to utilise inconsistencies in their present behaviours with identified goals, as a means of motivating change.

Motivational enhancement. This is a therapeutic approach that avoids confrontation, acknowledges and examines ambivalence, and assists the patient to utilise inconsistencies in their present behaviours with identified goals, as a means of motivating change. Relapse prevention skills. This set of techniques is learnt by the patient to prevent return to substance intake, particularly at times when there is high risk of use. It involves a behavioural analysis of substance-related behaviours, intervention that is tailored to the individual’s needs and the acceptance that temporarily lapsing back to use is possible but not catastrophic.

Relapse prevention skills. This set of techniques is learnt by the patient to prevent return to substance intake, particularly at times when there is high risk of use. It involves a behavioural analysis of substance-related behaviours, intervention that is tailored to the individual’s needs and the acceptance that temporarily lapsing back to use is possible but not catastrophic. Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT). CBT focuses on developing non-substance-related behavioural strategies, adaptive coping skills, and identifying and correcting any thinking errors.

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT). CBT focuses on developing non-substance-related behavioural strategies, adaptive coping skills, and identifying and correcting any thinking errors. Contingency management/behaviour modification. This strategy provides positive reinforcement for abstinence in structured treatment programs.

Contingency management/behaviour modification. This strategy provides positive reinforcement for abstinence in structured treatment programs. Acceptance and commitment therapy. This therapy involves the patient learning to accept what is out of their personal control and to focus on whatever is within their control to improve quality of life.

Acceptance and commitment therapy. This therapy involves the patient learning to accept what is out of their personal control and to focus on whatever is within their control to improve quality of life.Pharmacotherapy

There are evidence-based pharmacological approaches to some but not all substance-dependence disorders (see Table 20.7).

TABLE 20.7 Pharmacological treatments used in substance-dependence disorders

| Substance | Pharmacological options for management of dependence |

|---|---|

| Alcohol | Acamprosate, naltrexone and disulfiram |

| Benzodiazepines | Equivalent dose of diazepam and taper slowly |

| Heroin | Buprenorphine, buprenorphine/naloxone and methadone |

| Stimulants | Evidence lacking |

| Cannabis | Evidence lacking |

| Nicotine | Nicotine replacement therapies, bupropion and varenicline |

| Hallucinogens | Evidence lacking |

| Inhalants | Evidence lacking |

| Caffeine | Evidence lacking |

Social aspects

CASE EXAMPLES: substance abuse

Polydrug dependence

Treatment: Once detoxified, he can be helped to aim for abstinence as an intermediate if not long-term goal. Psychological approaches would depend on his preferences and progress; however, relapse-prevention strategies would be of paramount importance in the early stages, as would improving his self-efficacy. Given the early age of onset, multiple drugs, social chaos and interrupted personality development, it is highly likely that he will require some form of long-term rehabilitation, ideally initially in a therapeutic community followed by a residential program that involves learning basic life skills without drugs. Individual psychological work that addresses issues of anger, loss and mistrust (related to the death of his mother and perceived rejection from his family and community) would also be required.

References and further reading

Allsop S., editor. Responding to co-occurring mental health and drug disorders. Melbourne: IP Communications, 2008.

Baigent M.F. Physical complications of substance abuse: what the psychiatrist needs to know. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2003;16:291-296.

Kosten T.R., O’Connor P.G. Management of drug and alcohol withdrawal. New England Medical Journal. 2003;348:1786-1795.

Lubman D.I., Sundram S. Substance use in patients with schizophrenia: a primary care guide. Medical Journal of Australia. 2003;178:S71-S75.

Miller W.R., Rollnick S., editors. Motivational interviewing. New York: Guilford Press, 2002.

Prochaska J.O., DiClemente C.C., Norcross J.C. In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102-1114.

Saunders J.B., Aasland O.G., Babor T.F., et al. Development of alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption: II. Addiction. 1993;88:791-804.

Schuckit M.A. Drug and alcohol abuse: a clinical guide to diagnosis and treatment. New York: Springer, 2006.