Chapter 32 Submucosal uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

1 INTRODUCTION

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) is a widely accepted surgical procedure for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS)1 and the only one recommended by the American Sleep Disorders Association. Due to the inaccuracy of current diagnostic methods for preoperatively determining the level of upper airway obstruction in OSAHS patients, as well as the inherent technical limitations of UPPP in dealing the relevant anatomical factors, success rates in attainingobjective cure of about 40% after a long-term follow-up are far from desirable.2 Recent studies, however, have established a staging system that can result in success rates as high as 80% in select patients3 (see Chapter 16: Friedman Tongue Position and the Staging of Obstructive Sleep Apnea/Hypopnea Syndrome). In addition, UPPP is often part of a multilevel treatment strategy, which signifi-cantly improves success rates (see Chapter 17: Multilevel Surgery for Obstructive Sleep Apnea/Hypopnea). In addition to a considerable failure rate, complications of UPPP include nasopharyngeal stenosis, velopharyngeal insufficiency, pharyngeal dryness, hemorrhage, wound dehiscence, excessive palatal scarring, persistent dysphagia, and severe postoperative pain, not to mention rare but serious complications such as airway obstruction due to postoperative edema, leading to emergency reintubation or tracheotomy.4–7

Traditionally, UPPP is designed to eliminate palatal and pharyngeal redundancy by resection of excess loosepalatal and pharyngeal mucosal and submucosal tissue, in addition to tonsillectomy. The initial procedure, described by Fujita,8 as well as many other modifications, recommends excision of redundant mucosa, with a single-layer closure under tension. A widely accepted surgical principle is that epithelial surfaces should never be closed under tension. Repositioning of tissues should be accomplished at a muscular or subepithelial level, so that epithelium can be closed with minimal or no tension. The tense mucosal closure in traditional UPPP has resulted in two common sequelae.

Likewise, epithelial tension may also be responsible for common complications that contribute to failure of the procedure and require surgical correction.9

Since its description by Fujita in 1981,8 many authors writing about UPPP have actually re-described the original procedure, with important technical modifications. Submucosal UPPP focuses on the importance of epithelial preservation, and tension-free closure of the epithelium; and on the preservation of the majority of the mucosa of the soft palate and the anterior and posterior pillars. Elimination of palatal and pharyngeal tissue redundancy (the palatoplasty and the pharyngoplasty components, respectively) is accomplished by subepithelial and muscular stretching and closure. Epithelial closure is accomplished without tension.

2 PATIENT SELECTION

Candidates for surgical intervention must experience significant symptoms of snoring and/or daytime somnolence, documented failure of a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) trial, and documented failure of conservative measures such as dental appliances, changes in sleeping position, and sleep hygiene in general. Apparent obstruction at the level of the soft palate must be determined by fiberoptic nasopharyngolaryngoscopy and Mueller maneuver or sleep endoscopy. Adequate medical clearance and a thorough review of the procedure with the patient, as well as its implications, potential outcomes, and complications are essential components of the preoperative work-up.

Patient selection criteria for UPPP have been previously described by Friedman et al.3 (see Chapter 16: Friedman Tongue Position and the Staging of Obstructive Sleep Apnea/Hypopnea). Specific criteria for submucosal UPPP are the same as for classic UPPP, and include patients classified as Friedman Tongue Position (FTP) I or II with tonsil sizes 1–4. Patients with FTP III and IV are less than ideal candidates for UPPP, and should therefore undergo a combined procedure that addresses both the palate and the hypopharynx (e.g. radiofrequency base of the tongue reduction).10 An alternative technique, the Z-palatoplasty11 (see Chapter 33: Zetapalatopharyngoplasty), was developed as a more aggressive technique for patients with stage II and III disease. This includes all patients who have had previous tonsillectomy, as well as patients with small tonsils and those with unfavorable tongue positions.

3 SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

3.1 TONSILLECTOMY

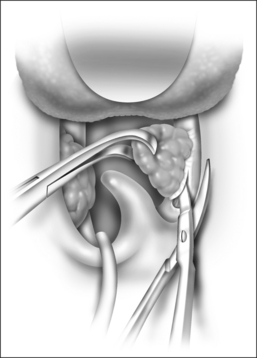

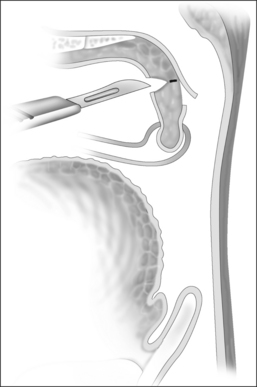

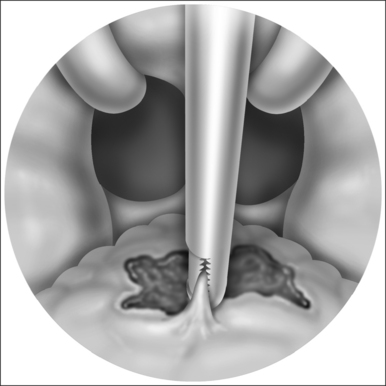

The tonsils, if present, can be excised using any technique, but the authors prefer the cold steel technique to minimize trauma to the anterior and posterior pillars. The tonsil is grasped with curved Allis forceps and pushed laterally to help identify the capsule. This allows for assessment of the lateral extent of the tonsil, and exposes the proper plane of dissection (Fig. 32.1). An incision through the anterior pillar and the posterior pillar is made, preserving as much tissue as possible. If necessary, excess anterior pillar can be trimmed at closure. Posterior pillar resection results in posterior pull of the palate, which decreases the retropalatal space. The dissection is carried out using Metzenbaum scissors or a Herd dissector, dividing the tonsil capsule from the superior constrictor muscle. Constant traction of the tonsil is maintained, allowing the tissue to separate as it is dissected. The removal of the tonsil proceeds within its anatomic boundaries, and the musculature of the tonsil fossa is left intact. Dissection is carried out inferiorly, towards the base of the tongue, and a snare is applied to complete the dissection. If done carefully, at the end of tonsillectomy, the tonsillar fossa is dry and the muscle fibers are still covered by fascia.

3.2 SUBMUCOSAL UVULOPALATOPHARYNGOPLASTY

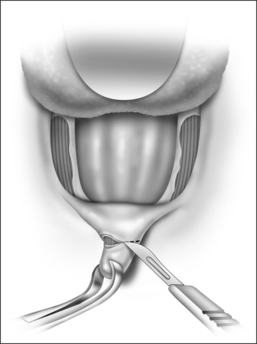

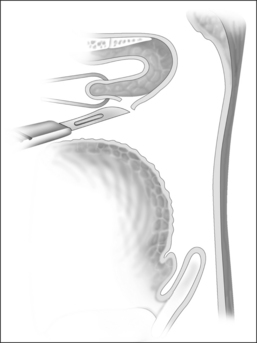

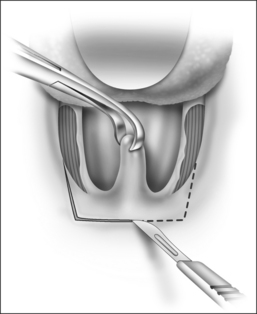

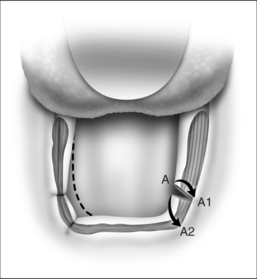

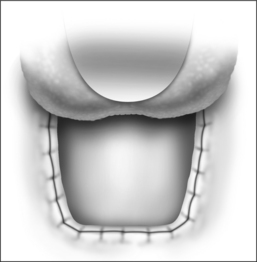

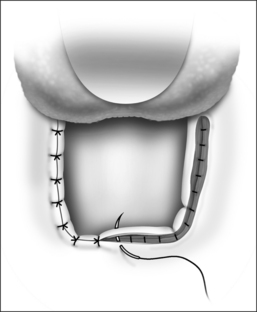

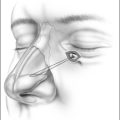

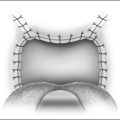

After removal of both tonsils, the palate is addressed. The uvula is grasped with Allis forceps and retracted anteriorly for optimal approach to the posterior surface of the soft palate. A curvilinear horizontal incision is made on the mucosa at the base of the uvula posteriorly, preserving almost the entire posterior soft palate mucosa (Fig. 32.2). Using a cold knife, the mucosa is separated from the muscle, releasing the posterior soft palatal mucosa. A trapezoid incision is outlined at the anterior mucosa of the soft palate (Fig. 32.3). This level is identified preoperatively in the awake patient, just below the ‘dimpled’ area. The incision is carried bilaterally and horizontally across the soft palate, until the anterior pillar starts sloping downward (Fig. 32.4). The uvula and the submucosal tissue of the lower edge of the soft palate are excised (Fig. 32.5). Based on Fairbanks’ technique, an incision dividing the superior third fromthe inferior two-thirds of the posterior pillar is perfor-med. The posterior pillar is then advanced anterolaterally, towards the corner of the palatal-pharyngeal junction(Fig. 32.6), which ultimately gives a squared appearance to the resected palate (Fig. 32.7). By including contiguous muscle fibers in this advancement, a more lateralizing effect isachieved, which expands the airway in the anterior-posterior(because of the forward pull) and lateral dimensions. Elimination of pharyngeal redundant folds is achieved by approximation of the submucosa and muscular tissue of the tonsillar fossa and the soft palate, using interrupted 2-0 Vicryl™ (Ethicon, Inc., Sommerville, NJ) sutures through the exposed pharyngeal musculature (Fig. 32.8). These sutures also prevent the formation of a dead space, where a seroma or hematoma might develop. The mucosal flap edges are then loosely approximated, taking care not to undermine, using 3-0 chromic sutures (Fig. 32.9).

4 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT ANDCOMPLICATIONS

Significant morbidity is observed during the first 24–72 hours postoperatively, in the form of significant pain and dysphagia. However, patients who undergo UPPP with tension-free closure show significantly less postoperative pain, when compared with patients post conventional UPPP.12 Clearly, a dehiscent suture line produces far more pain. The ability of the patient to tolerate at least a liquid diet, oral pain medications, antibiotics and steroids determines the need to keep the patient hospitalized. In general, patients diagnosed with moderate and severe OSAHS preoperatively are admitted to the intensive care unit for overnight monitoring. Most patients will need one or two days of intravenous fluids and medications before they can start taking an oral diet. Prior to discharge, patients are prescribed acetaminophen with codeine elixir as needed for pain. Pain medication requirements average 7–10 days. Postoperative antibiotics and steroids are also recommended, for a total of 7 days.

A summary of complications and the comparative incidence thereof between submucosal UPPP and UPP is listed in Table 32.1. Bleeding is always a potential complication and the risk is significant. Mild velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI) may manifest when drinking quickly, and may persist for up to 3 months. After 3 months, patients have normal deglutition. Severity of VPI symptoms diminish with time and it is expected to progressively resolve. Permanent VPI is a potential complication that must be considered in every patient. Additional morbidity of the procedure is usually related to throat discomfort symptoms, including globus sensation, mild dysphagia, dry throat, and inability to clear the throat. These symptoms are almost universal after any form of palatopharyngoplasty. Nasopharyngeal stenosis of varying degrees may occur, which may be caused by many factors, including the patient’s original anatomy.9 Fortunately, this is not a frequent complication after submucosal UPPP.12

Table 32.1 Comparison of narcotic medication use, returnto normal diet, and morbidity in a series of patientsundergoing uvulopalatoplasty and uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

| UPP (n=30) | UPPP (n=33) | |

|---|---|---|

| Postoperative narcotic use(in days) | 5.1±1.8 | 7.6±3.7 |

| Return to normal diet (in days) | 4.6±2.0 | 8.7±3.3 |

| Postoperative hemorrhage | 0% | 9.1% |

| Dysphagia | 10% | 18.2% |

| Foreign body sensation | 23.3% | 57.6% |

| Velopharyngeal insufficiency | 0% | 9.1% |

UPP, uvulopalatoplasty; UPPP, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty.

Modified from Friedman et al.13

5 SUCCESS RATE OF THE PROCEDURE

5.1 SUBJECTIVE AND OBJECTIVE SYMPTOM ELIMINATION

Subjective success is based on the assessment of patients and their bedpartners regarding symptom improvement, mainly snoring level and daytime sleepiness symptoms, by comparing these symptoms before and after treatment. Patients who underwent submucosal UPPP and the modified UPP technique achieved subjective improvement of symptoms in 97% and 87% of cases, respectively,13 which compares favorably to traditional UPPP. Significant improvement is achieved in quality-of-life parameters as well, as determined by the SF-36v2™ Quality of Life Survey. A greater degree of improvement is observed in several parameters, mostly bodily pain and psychological distress/well-being, which may relate specifically to less short- and long-term morbidity, particularly in the case of UPP, where by virtue of modification of the pharyngoplasty component of the technique, the major source of morbidity is eliminated.

5.2 WHAT TO DO IF THE PROCEDURE FAILS

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty failure is multi-faceted, as isOSAHS itself, which only stresses the importance of appropriate patient selection before performing any surgical intervention. Pan-airway obstruction, which may be present before surgery or may become manifest or more pronounced after UPPP, may be the source of failure. However, in up to 75% of patients, persistent retropalatal obstruction is usually the cause for initial failure orrecurrence of symptoms and deterioration in PSG parameters after UPPP.14 The first step should be a thorough investigation, in order to identify the site of failure. Sleep endoscopy evaluation may be a valuable test at this point. If the level of obstruction is confirmed to be retropalatal, a revision uvulopalatoplasty by Z-palatoplasty (ZPP) is one option for revision, with a success rate of about 68%15 (see Chapter 62: Revision Uvulopalatoplasty by Z-Palatoplasty [ZPP]). Transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty can also be considered as an alternative.16 In order to address the persistence of obstruction at the tongue base or hypopharyngeal level, genioglossus advancement alone or in combination with thyrohyoid suspension could be an option. Bimaxillary advancement should be kept in mind as a second-line procedure, if the above interventions fail. This procedure will correct failures at both the retropalatal and retrolingual levels.17

1. Littner M, Kushida C, Hartse K, et al. Practice parameters for the use of laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty: an update for 2000. Sleep. 2001;24:603-619.

2. Sher AE, Schechtman KB, Piccirillo JF. The efficacy of surgical modifications of the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1996;19:156-177.

3. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Joseph N. Staging of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome: a guide to appropriate treatment. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:454-459.

4. Fairbanks D. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty complications and avoidance strategies. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;102:239-245.

5. Katsantonis G, Friedman W, Krebs F, et al. Nasopharyngeal complications following uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:309-314.

6. Haavisto L, Suonpää J. Complications of uvulopalatopharyn-goplasty. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1994;19:243-247.

7. Kezirian E, Weaver E, Yueh B, et al. Incidence of serious complications after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:450-453.

8. Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, et al. Surgical correction of anatomic abnormalities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:923-934.

9. Krespi Y, Kacker A. Management of nasopharyngeal stenosis after uvulopalatoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:692-695.

10. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Lee G, et al. Combined uvulopalatopharyngoplasty and radiofrequency tongue base reduction for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:611-621.

11. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Vidyasagar R, et al. Z-palatoplasty (ZPP): a technique for patients without tonsils. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:89-100.

12. Friedman M, Landsberg R, Tanyeri H. Submucosal uvulopalato-pharyngoplasty. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;11:26-29.

13. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Lowenthal S, et al. Uvulopalatoplasty (UP2): a modified technique for selected patients. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:441-449.

14. Woodson B, Wooten M. Manometric and endoscopic localization of airway obstruction after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:38-43.

15. Friedman M, Duggal P, Joseph N. Revision uvulopalatoplasty by Z-palatoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:638-643.

16. Woodson B, Toohill R. Transpalatal advancement pharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:269-276.

17. Li K, Riley R, Powell N, et al. Maxillomandibular advancementfor persistent obstructive sleep apnea after phase I surgery inpatients without maxillomandibular deficiency. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1684-1688.