CHAPTER 16 Subglandular Breast Reduction

Key Points

Patient Selection

The subglandular breast reduction relies heavily on the ability of the youthful skin to retract and ‘shrink’ around a reduced breast mound. It will not correct a ptotic breast. It is thus more suited to the younger patient with firm to hard breast tissue1. A good guideline is that the outcome will be a smaller version of the breast shape that the patient had preoperatively (Figs 16.1–16.3) This relates especially to the relative position of the nipple to the breast mound.

Fig. 16.3 Patient 3 seen A–E preoperatively and F–J 1 year after left unilateral subglandular reduction.

Ideal patient selection for this technique (Table 16.1) follows the same indications as for liposuction; that is where the nipple–areola complex is sitting on the front of the breast and the breast is full and rounder in shape rather than ptotic and elongated. With ptotic breasts where the nipple–areola complex is sitting ‘underneath’ the breast rather than on the front a better shape and projection is obtained with pedicled techniques. It is the overall appearance and shape of the breast mound that is the best guide to technique selection, rather than measured distances of projected nipple areola movement. As with all breast reduction surgery the best results are obtained in those breasts requiring a smaller percentage volume reduction.

| Ideal candidate | Poor candidate |

|---|---|

| Round, firm breast tissue | Ptotic, fatty breast tissue |

| Nipple–areolar complex sitting anteriorly on the breast mound | Nipple–areolar complex sitting at lower pole of breast mound |

| Youthful elastic skin | Stretch marks and other signs of poor quality skin |

Indications

Despite the fact that a breast reduction brings great benefit to the patient the scars are a significant downside to the operation for the surgeon as well as the patient. It is the younger adolescent patient who is most likely to be disappointed by scarring. These girls are at a time in their life when they are forming sexual relationships for the first time. Visible scars on the breast are undesirable. Pers et al2 retrospectively looked at the results of 416 breast reduction patients. One-third found the resulting scars unacceptable. They found that it was the younger group of patients that made up the most of the unsatisfied patients.

Earlier techniques were based on the Wise pattern and resulted in the inverted T scars,3–6 which were long and visible. Since then different techniques have evolved to try and minimize these scars, including vertical mammaplasty7,8 and periareolar mammaplasty.9,10 It is not until recently that attention has re-focussed on eliminating the circumareolar and vertical components11–17 that are the most obvious to the patient, especially if the scar stretches or becomes hypertrophic.

This surgery is also indicated in the young women and girls who present with breast asymmetry. The operation technique is ideally suited to this situation, where only one breast needs to be reduced, correcting the asymmetry without visible scarring (Fig. 16.3).

Anatomical Background

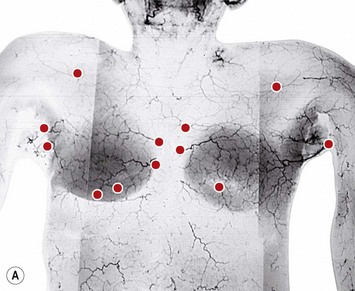

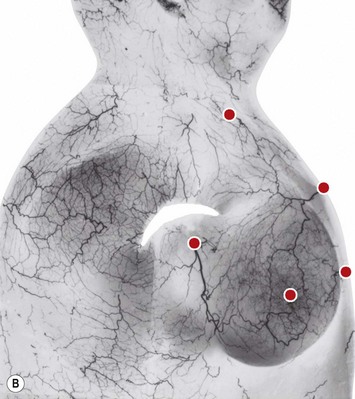

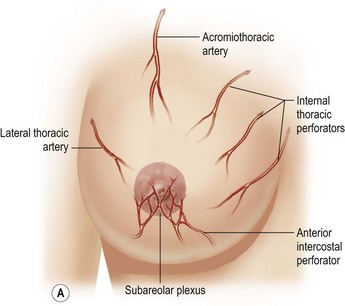

The dominant supply to the integument of the anterior chest is from: the internal thoracic artery medially, especially from the second and third interspaces; the lateral thoracic artery laterally; the anterior intercostal arteries inferiorly, especially from the fourth and fifth intercostal spaces in the region of the pectoralis major origin inferiorly and; from the acromiothoracic perforator and supraclavicular vessels superiorly. These vessels anastomose in the vicinity of the nipple–areola complex (Figs 16.4 and 16.5).

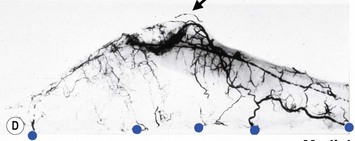

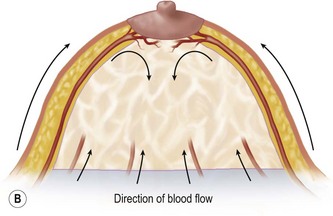

The breast in the female is a modified sweat gland. Like a tissue expander, it has enlarged from the skin at the nipple into the subcutaneous tissues, elongating these vessels from their fixed skin origins and compressing them towards the periphery of the gland (Figs 16.4, 16.5A, B) to form a vascular hood. Within the boundary of this vascular perimeter there is a relatively avascular mobile plane between the undersurface of the breast and the fascia over pectoralis major. This is utilized by the surgeon when introducing a breast prosthesis, after first dividing the vascular perimeter inferiorly.

These penetrating vessels interconnect with each other and with a smaller network of vessels on the undersurface of the breast (Fig. 16.4C, center and Fig. 16.5B). The venous drainage has a similar arrangement to the arterial supply with major veins travelling near, but not necessarily adjacent to, their arterial counterparts (Fig. 16.4D).

Technique

Markings

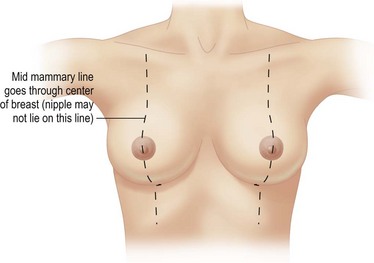

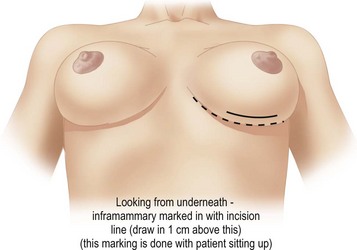

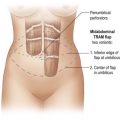

The patient is marked while sitting up. The midmammary line is drawn on the breast, dropped from the mid-clavicular point through the middle of the breast mound (Fig. 16.6). The nipple may lie outside this line. The desired areas of volume reduction are marked on the breast mound (Fig. 16.7). The inframammary crease is marked. The inframammary incision is marked approximately 1 cm above this so that it will fall into the new crease position (Fig. 16.8). The inframammary crease rises postoperatively as a result of less downward pull on the lighter breast mound. The incision is placed so that the medial and lateral ends of the resultant scar will not be visible when the patient is erect. It needs to be approximately 8 cm long to give sufficient access.

Operative procedure

With the patient lying flat a local anesthetic (ropivacaine 100 ml 0.2%) is injected in a ‘u’ around the periphery of the breast mound.12

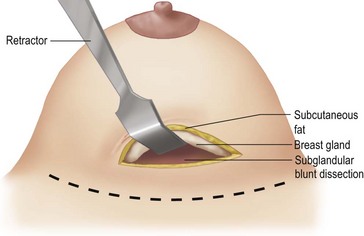

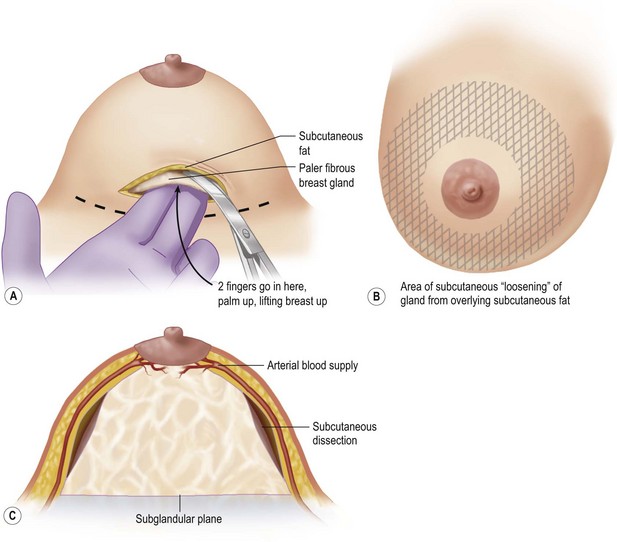

An incision of about 8 cm is made in the marked position. The subglandular plane is entered and a blunt dissection made, as in a submammary augmentation (Fig. 16.9). With the fingers in the subglandular plane the breast skin is dissected off the gland in a plane deep to the subcutaneous fat and on the ‘breast capsule’ – in the mastectomy plane. A ‘pushing’ technique with scissors is used. This plane is well demarcated in the young breast (Figs 16.10 and 16.11A). This is continued from inferior to the nipple–areolar complex in a circular fashion to surround the complex (Fig. 16.11B). This dissection is not taken under the nipple–areola complex. Lighted breast retractors are used to facilitate hemostasis. The blood supply is preserved outside this dissection (Fig. 16.11C).

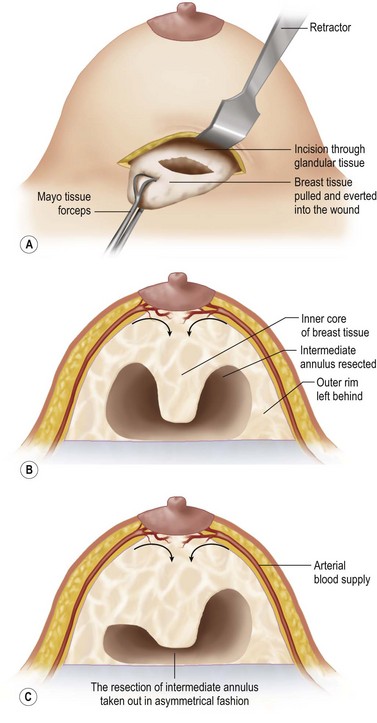

The intermediate annulus is removed from the undersurface of the breast. The outer rim is left so as to avoid damage to the vessels and to leave sufficient subcutaneous fat and breast tissue to avoid skin dimpling. The tissue is removed piecemeal with more tissue taken from the lateral side (Fig. 16.12A,B). Lighted breast retractors are used to facilitate hemostasis. Depending on the breast shape, an asymmetrical annulus or only a portion of an annulus, can be removed (Fig. 16.12C) The breast can be partially everted through the wound allowing selection of the areas to be removed (Fig. 16.12A) This degree of flexibility is advantageous when operating on the asymmetrical breast to match it to the other side.

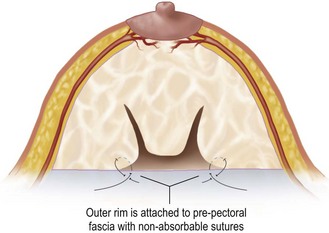

Eliminating the dead space created by removing the intermediate annulus narrows the base of the breast. The outer rim is approximated to the inner core with non-absorbable sutures (clear 0 Prolene; Johnson and Johnson, Somerville, NJ) from the outer rim to the prepectoral fascia (Figs 16.13 and 16.14).

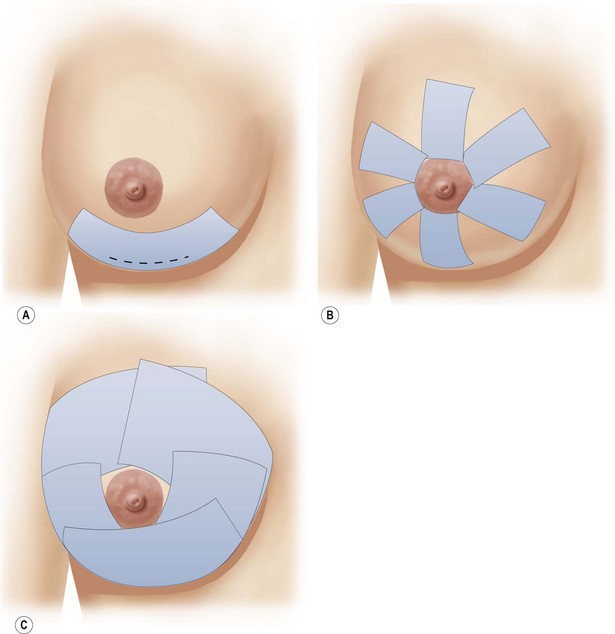

The taping of the breast mound to redistribute the skin is critical. 10 cm wide tape is placed over the lower pole to support the breast (Fig. 16.15A) Short strips of tape 5 cm wide are then placed in a radial fashion from around the nipple overlying the skin gathers (Fig. 16.15B). Further 10 cm wide tapes are then placed over the breast mound to give a semirigid support (Fig. 16.15C). The tapes are removed 2 weeks postoperatively and the patient wears two surgical bras, one outside the other, for a further 6 weeks both day and night. Occasionally it may be necessary to extend the period of taping to 4 weeks if when the initial tape is removed one feels that the breast would benefit from further tape support. The skin will continue to take up and the shape improve over a matter of months.

Pitfalls and How to Correct

A poor outcome will ensue when the skin does not retract as much as one wishes. It is important post operatively to use tape to encourage skin take up and to allow a full 12 months. If after 12 months the skin looks loose on the breast mound with the nipple sitting lower than the ideal then a surgical revision is then required to remove the extra skin. This is a minor procedure in which a periareolar skin resection is performed under local anesthetic (Figs 16.16 and 16.17). With good patient selection the likelihood of needing this revision is minimal.

Intraoperative judgment of the amount of tissue to resect is not easy when correcting asymmetry (Figs 16.18 and 16.19). One has to make a good estimate preoperatively of the volume of tissue to be resected and where from. The weight resected is always less than in a pedicled reduction for an equivalent volume reduction. Sitting the patient up intraoperatively while supporting the breast mound helps in the assessment.

1 Corduff N, Taylor GI. Subglandular breast reduction: the evolution of a minimal scar approach to breast reduction. Plas Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:175-184.

2 Pers M, Nielson IM, Gerner N. Results following reduction mammaplasty as evaluated by the patients. Ann Plast Surg. 1986;17:449-455.

3 Wise RJ. A preliminary report on a method of planning the mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1956;17:367.

4 Robbins T. A reduction mammoplasty with the areolar-nipple based on an inferior dermal pedicle. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:64-67.

5 Strombeck JO. Mammaplasty: Report of a new technique based on the two pedicle procedure. Br J Plast Surg. 1960;13:79.

6 McKissock P. Reduction mammoplasty with a vertical dermal flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;49:245-252.

7 Lejour M. Vertical mammaplasty and liposuction of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:100-114.

8 Marchac D, de Olorte G. Reduction mammaplasty and correction of ptosis with a short inframammary scar. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:45-55.

9 Bennelli L. A new periareolar mammoplasty: the round block technique. Aesth Plast Surg. 1990;14:93-100.

10 Felicio Y. Periareolar reduction mammoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;88(5):789.

11 Matarasso A, Courtiss EH. Suction mammoplasty: the use of suction lipectomy to reduce large breasts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(4):709-717.

12 Matarasso A. Suction mammaplasty: the use of suction lipectomy to reduce large breasts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(7):2604-2607.

13 Courtiss EH. Reduction mammoplasty by suction alone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1276.

14 Lejour M. Discussion of ‘Reduction mammoplasty by suction alone’ by EH. Courtiss Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1286.

15 Schoeller T. Refinements in reduction mammaplasties from a solely inframammary approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(3):1100-1105.

16 Alvo Z. Mammaplasty for mild and/or ptotic breast through short incision at the inframammary sulcus: a personal approach. Aesth Plast Surg. 1997;21:352.

17 Farrow H. Using Naropin (ropivacaine HCl) for blockade during reduction mammoplasty. Block of the Month; AstraZeneca. 2006.