CHAPTER 25 Subfascial Breast Augmentation

Summary/Key Points

According to the most accurate statistic databases all around the world, the number of breast augmentation procedures has been increasing over the years.1,2 The surgical approach, implant selection, and especially implant plane or pocket plane have been subjects of controversy. This chapter will discuss different approaches used to insert a breast implant subfascially, including anatomical considerations, patient selection and indications, operative techniques, advantages, pitfalls and postoperative care.

Anatomical Considerations

The breast is essentially a skin appendage contained within layers of the superficial fascia. The superficial layer of this fascia is near the dermis and is not distinct from it. The deep layer of the superficial fascia is more distinct and is identifiable when the breast is elevated in a subglandular augmentation mammaplasty.3 There is a loose areolar tissue between the deep layer of the superficial fascia and the fascia that covers the pectoralis major and continues to cover the adjacent rectus abdominis.4

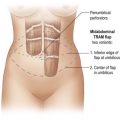

The pectoral fascia is a dense connective tissue that originates from the clavicle and sternum and covers the pectoralis major muscle and continues to cover the adjacent rectus abdominis, serratus anterior, external oblique muscle and extends toward the lateral border of the pectoralis major muscle to form the axillary fascia, as we can see in Figure 25.1. At the caudal border of the pectoralis muscle, the clavipectoral, pectoral, and serratus anterior fasciae become continuous and form the suspensory ligaments that extend to the breast inframammary fold.5

The pectoral fascia can be bluntly dissected along the subfascial plane and it has some specific characteristics. At the level of the second rib, the pectoral fascia tightly connects with the superficial fascia of the breast and it is difficult to dissect bluntly. Along the point that corresponds to the fourth intercostal space, the horizontal septum originating from the pectoral fascia connects with the nipple. At the inframammary crease, a dense connective tissue is found connecting the skin crease and the pectoral fascia. Fascial thickness has been found to vary from 0.2 to 1.14 mm along its different portions. Perforating vessels and nerves emerge mainly from the medial, lateral and lower part of the fascia.6

Patient Selection and Indications

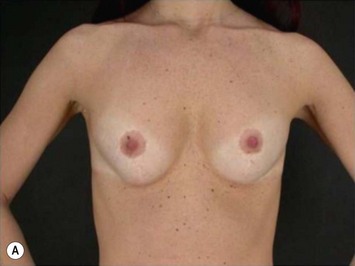

The pectoral fascia helps to support the implant and even in slim patients it gives a smoother transition in the upper pole of the breast, improving the final aesthetic result (Fig. 25.2).5,7,8 The exception would include thin patients who desire relatively large implants. In these patients it is better to use a round implant in the retromuscular pocket, or an anatomical/shaped implant subfascially (Fig. 25.3). Some other possible advantages clinically noticed with subfascial breast augmentation still need to be investigated. We have had the impression of reducing postoperative breast ptosis due to fascial support, and minimizing incidence of capsular contracture, possibly due to contact of the muscle fibers with the implant.

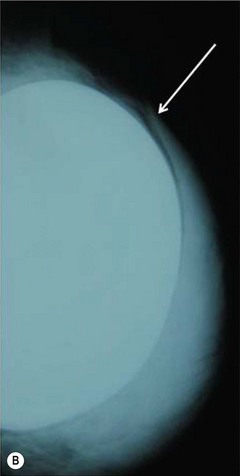

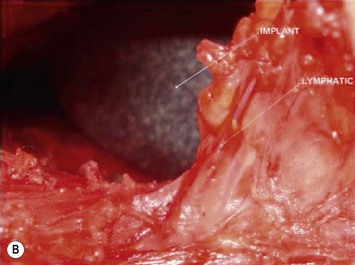

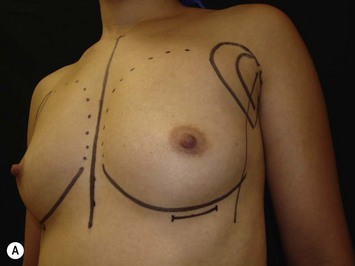

Transaxillary subfascial breast augmentation can be indicated for every patient who does not need mastopexy. Augmenting the breasts without leaving a scar on them is the major advantage in this technique and has been frequently desired by young patients (Fig. 25.4). The fact of creating a scar in a low tension area, far from the breasts, makes this approach the preferred technique in patients with known history or risk factors for hypertrophic scars and keloid. Preoperative conversation regarding axillary lymphatic drainage of the breasts and sentinel node implications is advisable. Recent studies published by our group showed that the sentinel node in the axilla can be preserved after transaxillary breast augmentation if some technical details during dissection are respected.9,10 This technique requires special instruments (long lighted retractors or video-endoscopic apparatus) and has a longer learning curve. Any kind of implant can be used through this access, however special attention should be given to avoid misplacement of anatomical implants.

The periareolar approach can be indicated for patients with medium or large size areolae, since the lower half perimeter of the areola must allow an incision of at least 4 cm. A well defined transition between areola and breast skin is also important to have a less visible scar. Patients who have breasts with mild ptosis that will probably not be corrected by the breast implant chosen are good candidates for a periareolar mastopexy (Fig. 25.5). Patients with tuberous breasts usually present with lower pole hypoplasia and some degree of nipple–areola complex weakness and prolapse. In these cases we have also used the circumareolar approach with nylon round-block suture to improve nipple–areola complex herniation. The subfascial pocket is created, but the fascia is radially incised in the lower breast in order to allow more skin distention. Round implants can be used for mild tuberous breasts, however in more severe cases anatomical shaped implants are better indicated to obtain greater lower pole projection.

The inframammary breast augmentation is the simplest and most direct access to insert silicone gel implants. It is not limited by the size of the implant, because the incision can be extended if necessary. It is also the most conservative approach relative to disturbing the breast parenchyma and preserving lymphatic drainage. The scars are usually of good quality and hidden under the brassiere (Fig. 25.6E). Correct planning of the incision is important to leave the final scar positioned right in the new inframammary fold. This approach can be indicated for every patient who is not a candidate for periareolar mastopexy, and for those patients with a previous history of hypertrophic scar or keloid. Disadvantages include a visible scar when the patient is lying down, greater risk of implant exposure compared to other approaches, and higher incidence of Mondor’s syndrome.11

Operative Technique

Surgical technique

There are some important details regarding the creation of the subfascial pocket.7,8 After the incision, the undermining of the subfascial plane should be done very carefully to avoid fascial injury and, if there is doubt about the plane, some muscle fibers may be lifted up with the fascia. Currently, we dissect using an eletrocautery device with a thin tip, set in the pure coagulation or blend cut mode. We prefer not to use the pure cut mode because of the risk of bleeding and the vessels going into the muscle, making dissection more difficult. Furthermore, with adequate surgical technique, it is possible to use the cutting mode very selectively, preventing additional unnecessary tissue damage.

The utilization of upward traction is necessary and facilitates the procedure, both in video-assisted and direct view approaches, making the dissection more precise and allowing the visualization of any bleeding spots. Limits for dissection are the second intercostal space superiorly, 1.5 cm from the midline medially, 5–7 cm below the areola to the new inframammary fold, and to the anterior axillary line laterally. The distance between implants should not be less than 2–3 cm, to prevent occurrence of synmastia,12 and the distance between the areola medial border and the midline should be about 9–10 cm.

Once dissection is completed, a meticulous evaluation for bleeding is carried out, and the implant is inserted into the pocket. Careful hemostasis is mandatory to avoid bleeding complications and late capsular contractures. To avoid leaving foreign body (cotton) in the pocket, it is prudent to avoid using gauzes or pads to clean up the space, but instead to irrigate it using normal saline solution. Implant sizers may be used to precisely choose the most appropriate implant. We routinely change and wash the new gloves just before handling the implants; and clean up again the skin around the incision with the antiseptic solution just before inserting the implants. We prefer not to use drains, due to the risk of infection.13

Axillary approach

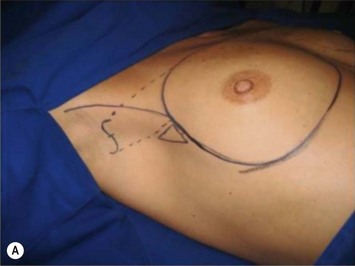

The axillary incision is placed in the local natural crease. An S-shaped, 4 cm long incision is performed in the main axillary fold, about 1 cm behind the lateral border of the major pectoralis muscle. It is important never to cross beyond the lateral edge of the pectoralis muscle. As we know, transaxillary breast augmentation can damage lymphatic vessels during subcutaneous tunnel dissection and insertion of the implant into the breast pocket. To minimize lymphatic injuries, subcutaneous tunnel should be dissected up to the superior lateral border of the muscle, preserving an inferior lateral triangle of soft tissue containing most of the lymphatic structures (Fig. 25.7).9,10

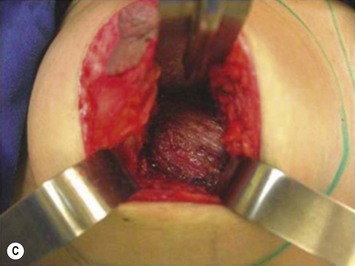

The pectoralis fascia is incised, and a subfascial breast pocket is dissected with electrocautery. It can be done using an endoscopic retractor or through direct view using long lighted retractors (Fig. 25.8).

Areolar approach

Periareolar breast augmentation can be performed with or without mastopexy. The skin is usually incised in the lower half of the areolar circumference, preserving the upper half as a superior pedicle for the nipple–areola complex. If a mastopexy is intended, a donut-area of skin is de-epithelialized, also preserving the upper half of the dermis. The inferior pole of the breast is dissected in an oblique direction, between the breast parenchyma and the subcutaneous tissue. Once the pectoral fascia is reached, it is incised approximately at the nipple level. The subfascial pocket is then created in all directions up to the marking limits (Fig. 25.9).

Another option of incision is the trans-areolar approach, which can be indicated for patients with an areolar diameter of at least 3.5 cm. A geometric broken line incision is done horizontally in the areola, merging and not transecting the nipple, without disturbing the lactiferous ducts or mammary gland.14 Dissection of the breast is performed as in the periareolar approach.

Inframammary approach

A 4-cm incision is made in the new proposed inframammary crease. The new inframammary fold and the incision should be carefully planned, in order to have a good quality and well placed scar. The site of the new inframammary fold and future scar should consider the implant diameter, the subcutaneous thickness, and skin elasticity. Gently stretching up the nipple–areola complex, the new inframammary fold distance from the nipple is marked adding the implant radius size and the subcutaneous thickness. This distance (nipple–new inframammary fold) usually ranges from 5 to 8 cm. After the skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised, the pectoral fascia is visualized and incised at the level of the areola, in order to create the subfascial pocket dissecting superior and inferiorly, as described above (Fig. 25.10).

Pitfalls and How to Correct

Implant displacement

Mild cases of implant displacement can be managed conservatively using modeling bra, elastic bands and breast massages trying to compensate for the differences. This is even more difficult in patients with textured implants. More severe and long-term cases will probably need reoperation to reshape the breast pocket with extra dissections or sutures (Fig. 25.11). Sometimes a subclinical seroma and double capsule can cause anatomical implant rotations.

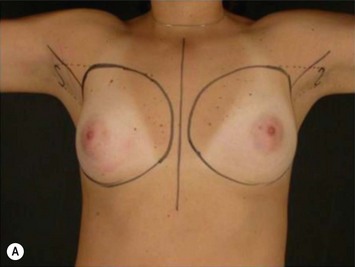

Preoperative asymmetry

Differences in breast sizes can be usually handled by using different implant volumes (Fig. 25.12). However, if large volumes (more than 50 cc) are necessary to improve the asymmetry, attention should be given to the base diameter and projection of the implants to avoid other asymmetries. When concomitant mastopexy is performed, excessive tissue from the larger breast can be resected, and the same or similar size of implants used.

Tuberous breast

Cases of mild to moderate grades of tuberous breast can be managed properly with a transaxillary subfascial breast augmentation (Fig. 25.13). However more severe cases must be treated with periareolar and circumareolar surgical access.

Submuscular implant mobilization

In some cases in which the patient presents with displacement of the implant with contraction of the pectoralis muscle, it is possible to achieve a good postoperative result with the change of the implant to the subfascial pocket (Fig. 25.14).

Thin patients and rippling

These patients represent a very challenging situation because of the absence of adequate tissue for covering the implant. We present a case that demonstrates the quality of natural contour with the utilization of the subfascial pocket. In a very small percentage of cases they can present with mild rippling that can be treated satisfactorily with fat grafting (Fig. 25.15).

Capsular contraction

Reoperation is still indicated for severe and non-reversible cases of capsular contracture. Depending on capsule thickness and restriction to the implant, capsulotomy (relaxing incisions), or partial or complete capsulectomy (capsule resection) can be performed (Fig. 25.16).

1. Spear SL, Bulan EJ, Venturi ML. Breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7 Suppl):188S-196S.

2. Hidalgo DA. Breast augmentation: choosing the optimal incision, implant, and pocket plane. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(6):2202-2216.

3. Hwang K, Kim DJ. Anatomy of pectoral fascia in relation to subfascial mammary augmentation. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55(6):576-579.

4. Würinger E, Mader N, Posch E, Holle J. Nerve and vessel supplying ligamentous suspension of the mammary gland. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(6):1486-1493.

5. Góes JC, Landecker A. Optimizing outcomes in breast augmentation: seven years of experience with the subfascial plane. Aesth Plast Surg. 2003;27(3):178-184.

6. Jinde L, Jianliang S, Xiaoping C, et al. Anatomy and clinical significance of pectoral fascia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7):1557-1560.

7. Graf RM, Bernardes A, Auersvald A, Damasio RC. Subfascial endoscopic transaxillary augmentation mammaplasty. Aesth Plast Surg. 2000;24(3):216-220.

8. Graf RM, Bernardes A, Rippel R, et al. Subfascial breast implant: a new procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:904.

9. Graf RM, Canan LWJr, Romano GG, Tolazzi AR, Cruz GA. Re: implications of transaxillary breast augmentation: lifetime probability for the development of breast cancer and sentinel node mapping interference. Aesth Plast Surg. 2007;31(4):322-324.

10. Sado HN, Graf RM, Canan LW, et al. Sentinel lymph node detection and evidence of axillary lymphatic integrity after transaxillary breast augmentation: a prospective study using lymphoscintography. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32(6):879-888.

11. Cornette de Saint Cyr B, Delmar H, Aharoni C. Approach to augmentation mammaplasty. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2005;50(5):451-462.

12. Spear SL, Bogue DP, Thomassen JM. Synmastia after breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(7 Suppl):168S-171S.

13. Araco A, Gravante G, Araco F, Delogu D, Cervelli V, Walgenbach K. Infections of breast implants in aesthetic breast augmentations: a single-center review of 3002 patients. Aesth Plast Surg. 2007;31(4):325-329.

14. Tenius FP, da Silva Freitas R, Closs Ono MC. Transareolar incision with geometric broken line for breast augmentation: a novel approach. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32(3):546-548.