CHAPTER 73 Structural fat augmentation of the face and hands

History

With renewed interest in volumetric enhancement for facial rejuvenation, fat grafting is once again gaining popularity. Fat grafting has been performed successfully for soft tissue augmentation since 1893, when Neuber first introduced the technique. This was followed by Eugene Hollander, who in 1909 described a technique to transplant fat using a needle and syringe and Conrad Miller, who in 1926 claimed that grafting fat through hollow metal cannulas gave a more natural and longer lasting correction than paraffin. In 1986, after the introduction of body contouring by suction curettage, Teimourian and Illouz described the injection of semi-liquid fat into liposuction deformities and Chajchir described injecting suctioned fat into the face. Some of the initial results were positive,1,2 however many were not3,4 and in the 1980s, many well-respected plastic surgeons felt that fat grafting was unreliable and denounced the procedure. As techniques improved so did the results and surgeons began to realize that grafted fat could result in long-lasting contour changes.5,6 The standard for fat grafting is now the Coleman technique, which emphasizes gentle handling of tissues to make fat grafting reliable and predictable.

Evaluation

• Loss of facial fullness resulting in hollowing, wrinkling, and/or mild skin laxity.

• Unnatural or unaesthetic facial proportions.

• Facial asymmetry secondary to trauma, surgery, and/or congenital abnormalities.

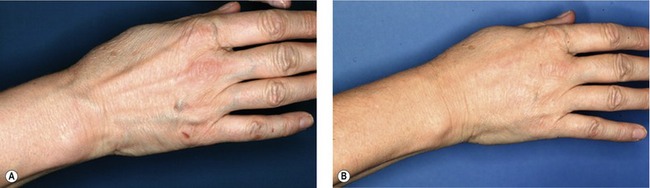

• Prominent dorsal hand veins and/or tendons with loss of fullness in the dorsal hand.

Anatomy

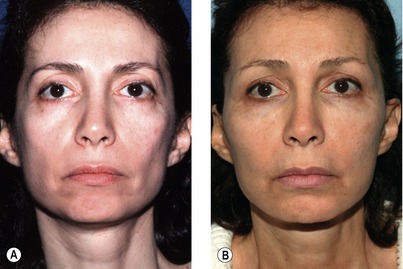

As the loss of facial volume depletes further, the secondary effect is that of descent of the overlying skin. A comparison of photographs of the patient at a younger age gives us valuable clues as to the individual aging process and the goals for surgical rejuvenation. If there is tremendous descent of the facial skin, a skin tightening/repositioning procedure is often needed. If the descent is more moderate, however, often the restoration of the underlying volume alone can reposition of the skin and improve the facial contours.

Technical steps

Placement

Fat grafting can be performed using either general, regional, or local anesthesia, depending on the extent of surgery being performed. Incisions for grafting the fat in the face, hands, or body are positioned such that fat can be placed from at least two different directions. A blunt Type I Coleman cannula is used for the placement of the local anesthetic in the areas of the face to be infiltrated with fat, but no local anesthetic is used in the hands or body other than at the points of incision. Either a blunt Type I, II, or III Coleman cannula is used for placement of the fat. Due to the risk of intravascular injection, sharp needles should be used with extreme care in the subcutaneous planes.7 To place the fat, the infiltration cannula is attached to a 1 mL (or 3 mL syringe for the body only) Luer-Lok syringe filled with refined tissue and the fat is distributed into the tissue as the cannula is withdrawn. Very small aliquots of fat (0.02–0.1 mL) are placed with each pass such that each parcel of fat is surrounded by native tissue. This ensures that each parcel of fat has access to a blood supply and also ensures stability of the transplanted tissue.

The planes of tissue placement for fat grafting can include the subdermal plane, subcutaneous plane, the muscle layer, and deep along the periosteum. The Coleman technique does not promote the intentional placement of fat into the muscle except in the body, such as in gluteal augmentation. When correcting significant bony or structural deficiencies it is usually essential to place fat deep along the periosteum and gradually add additional fat as you move superficially. Placement of fat in the subcutaneous plane gives a more significant volume change than the deeper grafts, and placement of fat in the subdermal plane can result in an improvement in skin texture over time (Fig. 73.1). In the hands, placement is just below the skin and above the extensor tendons and interosseous muscles (Fig. 73.2).

Intradermal placement was previously discouraged but is now being reconsidered.8 Using a sharp 22-gauge needle, small amounts of fat can be placed into the deep dermis of scars and deep wrinkles. This method of placement does not appear to be as reliable as the placement with a larger bore cannula, however, and is different from the subcision technique described by Carraway,1 who undermines an area first and then injects fat. The Coleman technique recommends placing the fat first, followed by the release of any remaining adhesions or scar tissue using a “v-dissector” or sharp needle. This maneuver, however, may destabilize the fat and should be delayed until the intradermal and subcutaneous placement is completed.

When learning fat grafting, the cheek is a good area to begin as the immediate results are very similar to the final results.9 The natural cheek prominence should be identified, the anterior cheek should be grafted to create a slight “apple” effect, and the fullness should extend laterally toward the base of the helix. Augmentation of the lips is also relatively easy, but the anatomy of an attractive lip is often ignored and the lips are filled like tubes or sausages. Fat should be grafted in the upper lip to create fullness in the white roll, the central tubercle and smaller lateral tubercles, and in the lower lip to emphasize a the central cleft, more lateral tubercles, and eversion of the vermillion.9,10 Augmentation of the chin is accomplished by first placing fat over the entire anterior aspect of the mandible9 and then refining the shape by leaving a small cleft between two higher prominences. A sharp, well-defined mandibular border can be created by placing fat deep along the periosteum as well as more superficially beneath the skin. The mandibular angle should be identified and emphasized if it is not visible and a continuous line should then be created from the angle to the chin. The lower eyelid is one of the most difficult areas to learn fat grafting, as irregularities, lumps, and excess fat can easily be seen through the thin eyelid skin. The lower eyelid should be approached with caution and only after experience in other more forgiving areas of the face.

Postoperative care

Lymphatic drainage with very light touch can help reduce swelling, but deep massage should be avoided in the first weeks after fat grafting to avoid displacing the fat. A minimum of two weeks, and sometimes as long as six weeks, is the usual recovery period for structural fat grafting to the face, hands, or body.9

Complications

Acute complications of fat grafting include bleeding/hematoma, which can be minimized with the use of a blunt cannula, and temporary injury to an underlying nerve or muscle. Occasionally edema in the area grafted can inhibit or alter normal muscle movement, but as the swelling resolves, patients generally recover completely. The most potentially devastating complication is an intravascular embolization.7 Fortunately this is extremely rare and has never been reported when using a blunt cannula. Sharp needles are therefore discouraged except when placing fat directly into the dermis. For similar reasons, injection guns should not be used and large boluses of fat should not be injected. Late complications include infections, which can result in resorption of the grafted fat, weight gain or loss with a concomitant change in the size of the area grafted, the placement of too much or too little fat with resultant contour deformities, and donor site defects. Strict sterile technique must be employed during this procedure and cannulas that penetrate the oral mucosa should be considered contaminated. Lip augmentation should be performed last if fat grafting is performed elsewhere on the face. Estimating the correct volume and precise placement techniques will improve over time and therefore decrease the incidence of contour irregularities. Donor site irregularities can be avoided with careful harvesting techniques and incisions can be lubricated with the oil obtained after centrifugation to minimize scarring. A more exhaustive description of potential complications9 and untoward effects has been published previously.

Pearls & pitfalls

Pearls

• Harvest fat gently with a 10 mL syringe to maintain intact tissue parcels.

• Refine the fat using centrifugation and decanting to increase predictability of results.

• Place very small (0.02–0.1 mL) aliquots of fat with each withdrawal of the cannula.

• Do not attempt to mold the grafted fat, but do ensure that it is smooth.

• Start slowly with more forgiving areas of the face and/or the hands.

Pitfalls

• Overcorrection is treatable, but is difficult.

• Fat grafting cannot address significant skin laxity.

• Structural fat grafting results in significant bruising and tissue edema.

• The volume of grafted fat can change with significant changes in body weight.

• Fat grafting remains somewhat unpredictable and is dependent on the operating surgeon, technique used to harvest, refine and place the fat, the recipient site injected, and individual patient characteristics.

1. Carraway JH, Mellow CG. Syringe aspiration and fat concentration: a simple technique for autologous fat injection. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;24(3):293–296.

2. Lewis CM. Transplantation of autologous fat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;88(6):1110–1111.

3. Ellenbogen R. Invited commentary on autologous fat injection. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;24:297.

4. Ersek RA. Transplantation of purified autologous fat: A 3-year follow-up is disappointing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(2):219–227.

5. Coleman SR. Long-term survival of fat transplants: Controlled demonstrations. Aesthet Plast Surg. 1995;19(5):421–425.

6. Trepsat F. Periorbital rejuvenation combining fat grafting and blepharoplasties. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2003;27(4):243–253.

7. Coleman SR. Avoidance of arterial occlusion from injection of soft tissue fillers. Aesthet Surg J. 2002;22(6):555–557.

8. Coleman S. Facial augmentation with structural fat grafting. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33(4):567–577.

9. Coleman SR. Structural fat grafting, 1st edn. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing; 2004.

10. Coleman SR. Lipoinfiltration of the upper lip white roll. Aesthet Surg J. 1994;14(4):231–234.