Chapter 59

Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack

1. What is stroke? How common is stroke? How common is it in the setting of cardiac disease?

2. What is a transient ischemic attack, and why is the clinical recognition of it important?

3. What are the major causes of stroke and TIA?

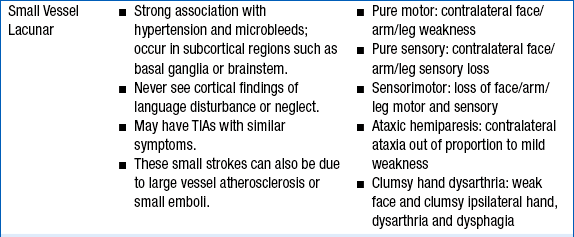

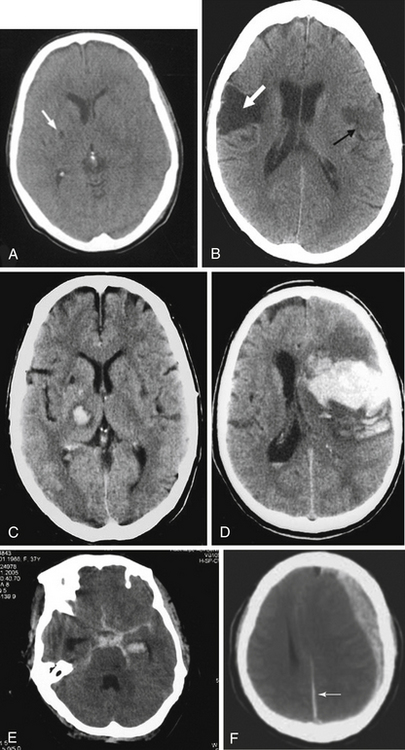

The major etiologies of ischemic stroke are cardioembolism, small vessel vasculopathy leading to lacunar stroke, and large vessel atherosclerosis (including intracranial atherosclerotic plaque rupture, as well as embolization from large arteries, such as the carotid, vertebral, and basilar arteries, to cerebral arteries [Fig. 59-1 and Table 59-1]). Hemorrhagic strokes include subarachnoid hemorrhage (usually due to aneurysm rupture) and intraparenchymal hemorrhage. Intraparenchymal hemorrhages are classified by their location: subcortical (associated with uncontrolled hypertension in 60% of cases) versus cortical (more concerning for underlying mass, arteriovenous malformation, or cerebral amyloid angiopathy; see Fig. 59-1). Figure 59-2 summarizes the major causes of stroke and their relative frequency.

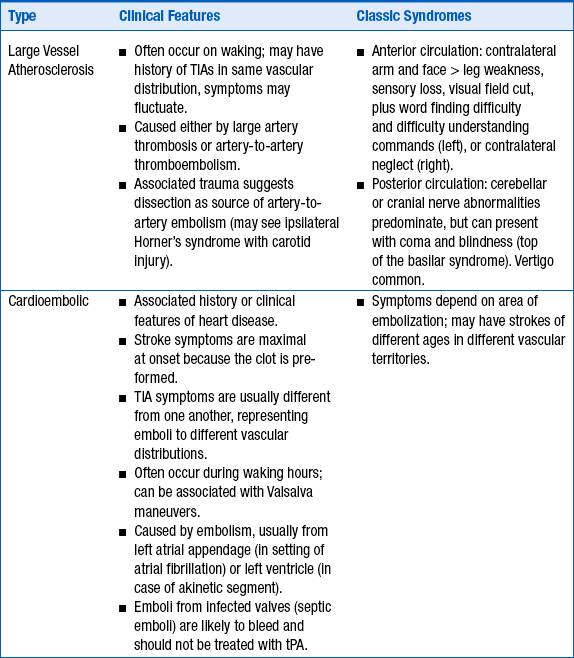

TABLE 59-1

CLINICAL FEATURES OF THE THREE MOST COMMON TYPES OF STROKE

TIA, transient ischemic attack; tPA, tissue plasminogen activator.

Figure 59-1 The computed tomographic findings of strokes and stroke mimics. A, Lacunar ischemic stroke, typical of small vessel disease; B, multiple ischemic strokes of different ages, typical of cardioembolism; C, Subcortical intraparenchymal hemorrhage; D, cortical intraparenchymal hemorrhage; E, subarachnoid hemorrhage; F, subdural hematoma, with a small amount of subarachnoid hemorrhage along the falx (arrow).

Figure 59-2 Relative frequencies of different types of stroke. (Compiled using data from the Greater Cincinnati Northern Kentucky Stroke Study.)

Among the other potential causes of stroke, dissection of the blood vessels needs to be considered, especially if there is face or neck pain or a history of trauma. Illicit drug use is a possible cause of either ischemic stroke (cocaine-, stimulants-, or “bath salts”–induced spasm) or hemorrhagic stroke (as a result of vascular injury or sudden massive increase in blood pressure). Patent foramen ovale (PFO) remains a controversial cause of stroke (see Question 18). Other, rarer, causes of stroke include hypercoagulable states (e.g., lupus and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome) and genetic disorders, such as homocystinuria and fibromuscular dysplasia.

4. How are stroke and TIA diagnosed?

Stroke and TIA are diagnosed clinically, and no imaging correlation is usually required for the diagnosis, although imaging procedures are performed to rule out other causes, such as tumor. Focal neurologic deficits with sudden onset should be considered as a vascular event until proven otherwise because of the possibility of recurrence or progression of the deficit. Focal weakness, numbness, facial asymmetry, or speech difficulties are classic presentations. Altered level of consciousness, vertigo, and cranial nerve deficits are often seen with vertebrobasilar-brainstem strokes. See Table 59-1 for lists of the clinical signs and symptoms of the major subtypes of stroke: large vessel atherosclerosis and thrombosis, cardioembolic stroke, and small vessel stroke.

5. What should be done in cases of suspected stroke or TIA?

A head CT must be performed immediately to distinguish ischemic from hemorrhagic strokes (see Fig. 59-1) because these are managed very differently. The CT itself does not diagnose stroke; it is primarily used to rule out causes other than ischemic stroke, including hemorrhagic infarction, tumor, subdural hematoma, and other causes. Figure 59-1 demonstrates the CT findings of strokes and stroke mimics.

tPA

The only medication approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for acute ischemic strokes is intravenous (IV) tPA, administered within 3 hours of symptom onset. Based on the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study III (ECASS III), American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines recommend treatment with IV tPA in selected patients out to 4.5 hours after symptom onset, but this is not yet approved by the FDA. Note, however, that the earlier tPA is given, the better the clinical outcome. The greatest benefit of tPA occurs at earlier time points. It is critical to give tPA as soon as possible if head CT does not reveal signs of hemorrhage or hypodensity. Only tPA is approved for acute stroke thrombolysis. Only eight stroke patients need to be treated with IV tPA to result in one patient with complete or near-complete recovery, and this number needed to treat (NNT) takes into account the increased risk of hemorrhage after tPA administration. Patients of any age benefit from tPA. Contraindications to IV tPA for the treatment of stroke are given in Box 59-1. Although tPA administration is not contraindicated in the setting of moderately elevated international normalized ratios (INR of 1.3-1.7), recent studies suggest an increased risk of brain hemorrhage compared to tPA administraton with a normal INR. Importantly, patients who have their strokes after cardiac catheterization and who meet these criteria may still benefit from tPA, despite the recent administration of heparin and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, although this is outside the usual protocols and should be done only with expert help. In this situation, various treatments have been reported, including intraarterial therapy or IV abciximab, but these uses remain investigational.

Endovascular devices for cerebral clot disruption/retrieval are FDA approved, although their efficacy for improving outcome has yet to be demonstrated. The Interventional Management of Stroke 3 trial did not show a benefit of combined IV tPA plus endovascular treatment over IV tPA alone. At this time, endovascular treatment of acute stroke is often suggested in patients who present early but are ineligible for IV tPA because of anticoagulation or another condition posing an unacceptably high risk of systemic bleeding, but ongoing randomized trials may clarify their exact role.

Hemicraniectomy

7. How are hemorrhagic strokes managed?

8. What other measures are important in the management of all strokes?

9. Is the presence of atrial fibrillation in patients with stroke or TIA an important consideration for future management?

Yes. Any patient with atrial fibrillation who has had a stroke or TIA is considered at high risk for future strokes without anticoagulation (see Question 11). As such, all patients should be monitored with telemetry to optimize identification of intermittent (paroxysmal) atrial fibrillation, because intermittent atrial fibrillation is as much of a risk factor for stroke as persistent atrial fibrillation. A single ECG (unless it reveals atrial fibrillation) is inadequate for detection of this important risk factor. Prolonged event monitors reveal subclinical atrial fibrillation in a substantial proportion of patients with cryptogenic stroke, and are warranted in cases where clinical suspicion is high.

10. What is the utility of echocardiogram for workup of acute stroke?

In stroke patients with a suspected cardioembolic cause, echocardiogram is indicated (see also Chapter 5 on echocardiography). Transesophageal echocardiogram is often performed in patients with suspected embolic stroke and a nondiagnostic transthoracic echocardiogram. An echocardiogram is not needed to determine secondary stroke prevention strategies for stroke patients with known atrial fibrillation, because these patients should be anticoagulated; however, identification of a cardiac thrombus would affect timing of anticoagulation initiation and may have some prognostic value.

11. Which patients with atrial fibrillation merit anticoagulation therapy for the prevention of stroke?

All patients with history of stroke and atrial fibrillation merit consideration for anticoagulation, because the risk of subsequent stroke in these patients is 2% to 15% per year and anticoagulation results in a greater than 60% reduction in ischemic strokes. Other high-risk groups include those over the age of 75 (especially women) and those with the following risk factors: poorly controlled hypertension, diabetes, and poor left ventricular function or recent heart failure. A number of risk stratification schemes can help determine which patients should be anticoagulated to prevent stroke. These include CHADS2 (see Fig. 34-1), Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation (SPAF), Atrial Fibrillation Investigators (AFI), and Framingham, among others. These schemes integrate risk factors to assist in the decision for anticoagulation therapy: The greater the number of risk factors, the higher the risk of stroke. It is important to note that these schemes relate to primary prevention in atrial fibrillation; a stroke or TIA automatically places a patient in the high-risk category for each of these schemes. As such, secondary prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation should involve anticoagulation unless there is a contraindication. The elderly also appear to benefit from anticoagulation for secondary stroke prevention; thus, age alone is not a contraindication, although elderly patients are at higher risk for bleeding.

12. What are the benefits and risks of the newer anticoagulants for stroke prevention in the setting of atrial fibrillation?

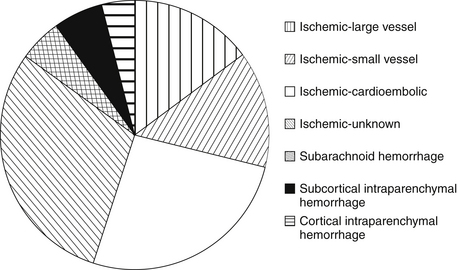

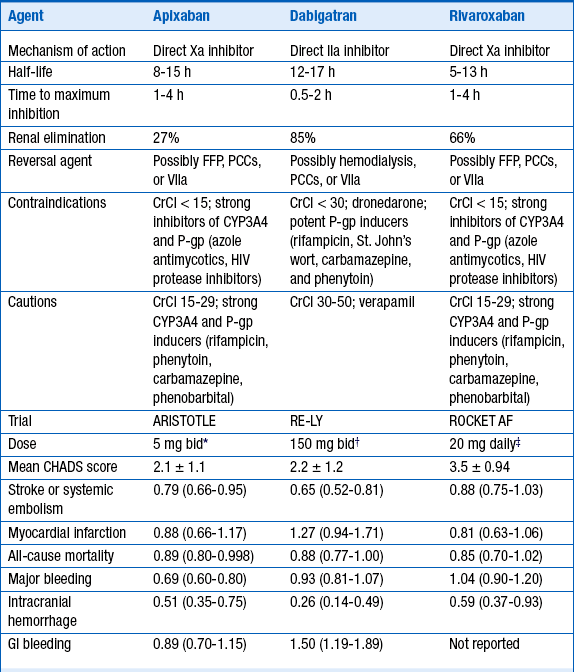

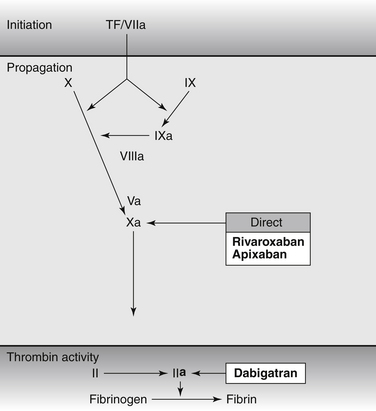

New oral anticoagulants include the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran and the factor Xa inhibitors apixaban and rivaroxaban (Fig. 59-3). Dabigatran and apixaban were superior to warfarin in preventing vascular events and death in large randomized controlled trials of subjects with atrial fibrillation; rivaroxaban was noninferior to warfarin. The benefit of these agents over warfarin is due to better efficacy for stroke prevention, as well as lower overall bleeding risk (Table 59-2). The most serious complication of anticoagulation is intracerebral hemorrhage, which was reduced substantially with these agents. Subgroup analysis of the dabigatran trial found that concomitant aspirin use increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage 1.6-fold. Dabigatran and rivaroxaban had a higher rate of GI bleeding relative to warfarin; apixaban showed no such trend. Dabigatran has shown a small but consistent increase in myocardial infarction (MI) compared to warfarin, although it decreases overall vascular events and mortality.

TABLE 59-2

SUMMARY OF MECHANISM AND CLINICAL TRIALS OF THE NEWER ANTICOAGULANTS USED FOR STROKE PREVENTION IN ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

∗2.5 mg dose in subjects >80 years, body weight ≤ 60 kg, or serum creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dL.

Figure 59-3 Targets of Novel Anticoagulants for Long-Term Use. Dabigatran etexilate is a prodrug that generates active compounds able to bind directly to the catalytic site of thrombin (factor II); rivaroxaban and apixaban are direct FXa inhibitors. Warfarin inhibits synthesis of factor II, factor VII, factor IX and factor X. Unfractionated heparin, low molecular weight heparin, and fondaparinux indirectly inhibit factor II and/or factor Xa. (Adapted from De Caterina R, Husted S, Wallentin L, et al: New oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation and acute coronary syndromes: ESC Working Group on Thrombosis-Task Force on Anticoagulants in Heart Disease position paper. J Am Coll Cardiol 59(16): 1413–25, 2012.)

13. Are there options other than anticoagulation for secondary stroke prevention in the setting of atrial fibrillation?

14. Which patients merit antiplatelet therapy for prevention of stroke? What is the benefit? What are the risks?

All patients who do not meet criteria for anticoagulation after stroke should receive antiplatelet therapy with either (a) aspirin, (b) clopidogrel, or (c) aspirin plus extended release dipyridamole. These three agents are similarly efficacious for stroke prevention, decreasing risk of second stroke by 14% to 18%. Ensuring optimal compliance with antiplatelet therapy is more important than the individual agent used, so the choice of agent should be guided by comorbidities, tolerability, and cost. Clopidogrel may be preferred in patients with history of significant GI bleeding, peripheral vascular disease, or drug-eluting cardiac stents. Aspirin plus dipyridamole can cause headaches initially and so may be difficult to tolerate for patients with chronic headache. The Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes (PROFESS) trial comparing clopidogrel with aspirin plus extended release dipyridamole found that neither regimen was superior; each regimen had a somewhat different side-effect profile. Aspirin alone may be a good choice when not contraindicated, particularly when cost of the alternative agents would hinder compliance.

Aspirin should not be used in combination with clopidogrel for long-term secondary stroke prevention, as the combination showed an unacceptably high bleeding risk without additional protection from strokes, compared with either aspirin alone (in lacunar stroke patients) or clopidogrel alone (in all stroke patients), particularly after 90 days. However, the Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial used aspirin plus clopidogrel for 90 days followed by aspirin alone in their management of high-risk intracranial stenosis patients with better-than-expected outcomes, although this regimen was not compared to a single-agent regimen. Patients may require both aspirin and clopidogrel for cardiac conditions such as drug-eluting stents, and such patients may be continued on this combination regimen after stroke, with an understanding that bleeding risk may be elevated.

15. How soon after a stroke or TIA should anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy be initiated?

In general, antiplatelet therapy can be initiated immediately in patients who are not candidates for tPA and do not have any indication of hemorrhagic component, and after 24 hours in patients who received tPA once lack of hemorrhage has been confirmed by imaging. Timing of anticoagulation is highly case-specific. Larger strokes are more likely to bleed than small strokes, especially early on. The risk of a second stroke in the 2 weeks after initial stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation is only 0.5% (in the absence of a known cardiac thrombus). The risk of bleeding from full dose heparinization of 1 week duration has been estimated at 5% based on the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) trial. Because of this, it is common practice to wait 1 month after a large stroke before initiating anticoagulation, although such a strategy has not been prospectively studied in a large trial. Patients with very small strokes may be started on anticoagulation within 1 or 2 days of stroke. The decision is much more difficult in patients with large strokes at higher risk for embolization, such as those with mechanical valves or demonstrated cardiac thrombus. In such cases, oral anticoagulation may be started cautiously after 5 to 15 days, depending on the individual situation. Retrospective data suggest bridging with heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin causes higher bleeding risk. In the absence of clinical or laboratory evidence of a hypercoagulable state, it is probably acceptable to start warfarin at low doses to achieve therapeutic anticoagulation slowly. Some clinicians suggest use of aspirin until an INR of 2 is achieved.

16. How should patients with carotid stenosis be managed?

17. How should patients with intracranial stenosis be managed?

18. How should patients with stroke and patent foramen ovale be managed?

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Adams, H.P., Jr., Bendixen, B.H., Kappelle, L.J., et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST: Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41.

2. Archives of Internal Medicine [No authors listed] . Risk factors for stroke and efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation. Analysis of pooled data from five randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1449–1457.

3. Furie, K.L., Kasner, S.E., Adams, R.J., et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(1):227–276.

4. Giraldo, E.A. Stroke (CVA). Available at http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/neurologic_disorders/stroke_cva/overview_of_stroke.html. Accessed March 26, 2013

5. Jauch, E.C., Kissela, B., Stettler, B. Acute Management of Stroke. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1159752-overview. Accessed March 26, 2013

6. Jauch, E.C., Saver, J.L., Adams, H.P., Jr., et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease, and Council on Clinical Cardiology: Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;4(3):870–947.

7. Morgenstern, L.B., Hemphill, J.C., 3rd., Anderson, C., et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing: Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2010;41(9):2108–2129.

8. Khatri, P., Taylor, R.A., Palumbo, V., et al. The safety and efficacy of thrombolysis for strokes after cardiac catheterization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:906–911.

9. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and Boston University. The Framingham Heart Study risk score profiles. Available at www.framinghamheartstudy.org/risk. Accessed March 26, 2013

10. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587.

11. Schneck, M.J., Xu, L. Cardioembolic Stroke. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1160370-overview. Accessed March 26, 2013