Chapter 2 Stroke

Introduction – time is brain

According to The Stroke Association (2010), every 5 minutes, someone in the UK has a stroke. This means that in Great Britain alone, approximately 150,000 people have a stroke every year. Stroke is the third biggest cause of death and the biggest cause of adult disability.

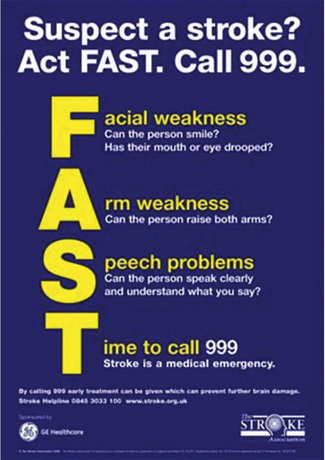

A stroke is a medical emergency and anyone suspected of having a stroke should be taken to Accident & Emergency immediately. The UK Stroke Association aims to raise stroke awareness and has organized the FAST campaign (Figure 2.1). FAST is an acronym standing for Face, Arm, Speech, Time to call 999. When you suspect someone is having a stroke, test facial weakness (can the person smile?), arm weakness (can the person raise both arms?) and speech problems (can the person speak clearly and understand what you say?). If the answer to any of these questions is no, the person might have a stroke so it is time to call 999 – because stroke is a medical emergency.

Making a prognosis directly after stroke is difficult and depends on a variety of factors, which will be presented later in this chapter. Overall, approximately 20% of patients having their first stroke are dead within a month, and of those alive at 6 months approximately one-third are dependent on others for activities of daily living (Warlow, 1998).

Definitions

A stroke or cerebrovascular accident (CVA) is typically defined as an accident with ‘rapidly developing clinical signs of focal or global disturbance of cerebral function, with symptoms lasting 24 hours or longer or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than of vascular origin’ (WHO, 1988).

Classification and aetiology of stroke

Strokes are classified into two main categories: ischaemic or haemorrhagic (Amarenco et al., 2009). An ischaemic stroke is caused by an interruption of the blood supply. A haemorrhagic stroke is caused by a ruptured blood vessel. The majority of strokes are ischaemic accidents (approximately 80%).

The main causes of ischaemic stroke are:

Strokes are thus typically classified as ischaemic or haemorrhagic. Ischaemic strokes are commonly further classified according to the Oxford Community Stroke Project (OCSP) classification, also known as the Oxford or Bamford classification (Bamford et al., 1991). This classification distinguishes between a:

Anatomy and pathophysiology

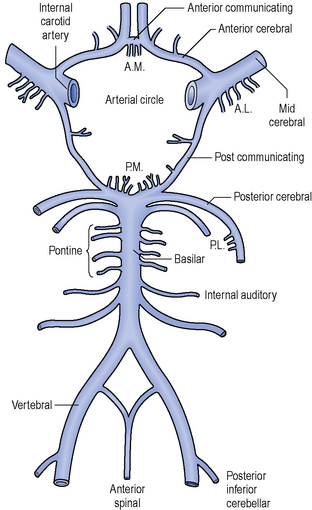

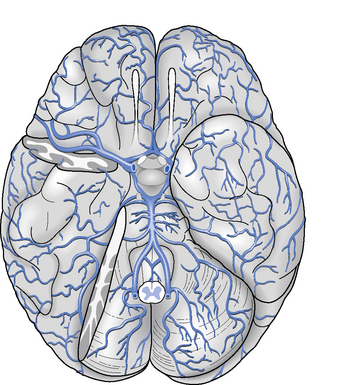

The arteries that supply blood to the brain are arranged in a circle called the Circle of Willis (Figure 2.2), after Thomas Willis (1621–1673), an English physician. All the principal arteries of the Circle of Willis give origin to secondary vessels which supply blood to the different areas of the brain (Figure 2.3).

When an ischaemic stroke occurs and part of the brain suffers from lack of blood, the ischaemic cascade starts. Without blood the brain tissue is no longer supplied with oxygen and after a few hours in this situation, irreversible injury could possibly lead to tissue death. Because of the organization of the Circle of Willis, collateral circulation is possible, so there is a continuum of possible severity. Part of the brain tissue may die immediately while other parts are potentially only injured and could recover. The area of the brain where tissue might recover is called the penumbra. Ischaemia triggers pathophysiological processes which result in cellular injury and death, such as the release of glutamate or the production of oxygen free radicals. Neuroscience research is constantly studying ways to inhibit these pathophysiological processes by means of developing neuroprotective agents (Ginsberg, 2008).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of stroke is based on a clinical assessment and imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. For diagnosing an ischaemic stroke in the acute setting, an MRI scan is preferred, as sensitivity and specificity are higher in comparison with CT imaging (Chalela et al., 2007). For diagnosing ischaemic strokes, CT and MRI scan have comparable sensitivity and specificity.

Early medical treatment

In the case of an ischaemic stroke, the more rapidly the blood flow is restored to the brain, the fewer brain cells die (Saver, 2006). Hyperacute stroke treatment is aimed at breaking down the blood clot by means of medication (thrombolysis) or mechanically removing the blood clot (thrombectomy). Other acute treatments focus on minimizing enlargement of the clot or preventing new clots from forming by means of medication such as aspirin, clopidogrel or dipyridamole. Furthermore, blood sugar levels should be controlled and the patient should be supplied with adequate oxygen and intravenous fluids.

Thrombolysis is performed with the drug tissue plasminogen activator (tPA); however, its use in acute stroke is controversial. It is a recommended treatment within 3 hours of onset of symptoms as long as there are no contraindications, such as high blood pressure or recent surgery. tPA improves the chance of a good neurological outcome (The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group, 1995). In a recent study, thrombolysis has been found beneficial even when administered 3 to 4.5 hours after stroke onset (The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study, 2008). However, another recent study showed mortality to be higher among patients receiving tPA versus those who did not (Dubinsky & Lai, 2006).

Another intervention for acute ischaemic stroke is the mechanical removal of the blood clot. This is done by inserting a catheter into the femoral artery, which is then directed into the cerebral circulation next to the thrombus. The clot is then entrapped by the device and withdrawn from the body. Studies have shown beneficial effects of thrombectomy in restoring the blood flow in patients where thrombolysis was contraindicated or not effective (Flint et al., 2007).

Prognosis and recovery

Van Peppen and colleagues (2007) have performed a systematic review of prognostic factors of functional recovery after stroke. They investigated walking ability, activities of daily living, and hand and arm use after stroke.

Walking ability (defined as a Functional Ambulation Category (Holden et al., 1984) score ≥4) at 6 months after stroke was best predicted by initial walking ability in the first 2 weeks after stroke, degree of motor paresis of the paretic leg, homonymous hemianopia, sitting balance, urinary incontinence, older age and initial ADL functioning in the first 2 weeks after stroke (Kwakkel et al., 1996).

The Barthel Index score (Mahoney & Barthel, 1965) in the first 2 weeks after stroke appeared to be the best prognostic factor for recovery of independence in activities of daily living at 6 months after stroke. Other contributing predictors were urinary incontinence in the first 2 weeks after stroke, level of consciousness in the first 48 hours after stroke, older age, status following recurrent stroke, degree of motor paresis, sitting balance in the first 2 weeks after stroke, orientation in time and place, and level of perceived social support (Kwakkel et al.,1996; Meijer et al., 2003).

The best clinical predictor of recovery of dexterity of the paretic arm 6 months after stroke appeared to be severity of arm paresis at 4 weeks after stroke, measured by Fugl-Meyer Arm Assessment (Kwakkel et al., 2003). Other studies also identified severity of the upper extremity paresis, voluntary grip function of the hemiplegic arm, voluntary extension movements of the hemiplegic wrist and fingers within the first 4 weeks after stroke, and muscle strength of the paretic leg (Heller et al., 1987; Kwakkel et al., 2003; Sunderland et al.,1989).

Hendricks et al. (2002) conducted a systematic review of the literature of motor recovery after stroke. They concluded that approximately 65% of the hospitalized stroke survivors with initial motor deficits of the lower extremity showed some degree of motor recovery. For patients with paralysis, complete motor recovery occurred in less than 15% of cases, both for the upper and lower extremities. The recovery period in patients with severe stroke appeared twice as long as in patients with mild stroke.

There are several studies indicating that most of the overall improvement in motor function occurs within the first month after stroke, although some degree of motor recovery can continue in patients for up to 6 months after stroke. Verheyden et al. (2008) compared the recovery pattern of trunk, arm, leg and functional abilities in people after ischaemic stroke. They assessed participants at 1 week, 1 month, and 3 and 6 months after stroke. There appeared to be no difference in the recovery pattern of trunk, arm, leg and functional ability and, for all measurements, most (significant) improvement was noted between 1 week and 1 month after stroke. There was still a significant improvement between 1 month and 3 months after stroke, but between 3 and 6 months participants showed no more significant improvement. Further exploration of this latter period saw some participants stagnate in trunk, arm, leg and functional recovery and others deteriorate. Deterioration in people after stroke has been demonstrated in other (long-term) studies (van de Port et al., 2006). But despite evidence of stagnation, deterioration or a plateau phase, there is substantial secondary evidence concerning late recovery, i.e. several months after stroke, although most of these studies were in (outpatient) rehabilitation centres and thus included selected patient populations. Nevertheless, Demain et al. (2006) suggested that the notion ‘plateau’ is conceptually more complex than previously considered and that ‘plateau’ not only relates to the patients’ physical potential, but is also influenced by how recovery is measured, the intensity and type of therapy, patients’ actions and motivations, therapist values and service limitations.

Outcome measures

Milestones of stroke rehabilitation should be documented by means of standardized outcome measures (Stokes, 2009). There is an increasing number of tools available. Van Peppen et al. (2007) have performed a systematic review of outcome measures for people with stroke. They propose a core set of outcome tools based on consistency with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (WHO, 2001); high-level psychometric properties (i.e. inter- and intrarater reliability, validity and responsiveness); good clinical utility (easy and quick to administer); minimal overlap of the measures and consistency with current physiotherapy practice. The core outcome measures proposed for people with stroke based on their review were:

Van Peppen et al. (2007) also propose a set of 18 optional outcome measures, to be used to evaluate a specific function or activity in people with stroke. These optional outcome measures are:

Clinical utility of an outcome measure is probably a key aspect and often authors have neglected this area in the past. A recent study by Tyson and Connell (2009) looked at how to measure balance in clinical practice. They performed a systematic review of measures of balance activity for neurological conditions. They scored not only psychometric properties, but also clinical utility by assigning scores to the time taken to administer, analyse and interpret the test, the costs of the tool, whether the measure needs specialist equipment and training, and whether the measurement tool is portable. They evaluated 30 measures and after excluding 11 based on limited psychometric analysis or inappropriate statistical tests used, they recommended the following balance tools for people with stroke:

Principles of physical management

Time course

The National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008) and the National Strategy for Stroke (Department of Health, 2007) include recommendations that people who have had a stroke are ideally managed in a stroke unit by a specialist multidisciplinary team. Even so, there are different types of clinical services, pathways and, indeed, stroke units throughout the country with varying criteria for admission and discharge. Organized services with specialist multidisciplinary teams have been identified as key to a positive outcome. A physiotherapist should expect to work with other health-care staff dedicated to the care of people with stroke and to contribute to the process of problem solving and decision making involved in the overall management. Although stroke rehabilitation commences in the acute stage on admission to hospital, active participation in the relearning of mobility and independence broadly takes place during the sub-acute and long-term stages post stroke. These three stages are rarely distinctive, they frequently overlap and do not always follow the same time frame or order for everyone, but there are common patterns. In addition, the process of transferring from hospital or rehabilitation setting and discharge from services requires structured management and should be carefully planned to be effective.

Acute stage

Patients in the acute stage can be at different levels of consciousness; they may be sedated and intubated (Kilbride & Cassidy, 2009a) or they may be able to communicate with or without difficulty. It is essential to find out if the person is medically stable before commencing physiotherapy treatment; talk to key members of the hospital team and read the medical notes. Find out the age of the patient, the type of stroke, blood pressure, ability to communicate, if an injury occurred at the time of their stroke and information about their medical history, for example have they experienced a previous stroke or do they have dementia? An outline of their social environment may also provide a guide on cultural issues and language differences. It is important to be informed of those potential risk factors that may influence what a physiotherapist does and the treatment planned. It is essential to report to nursing staff and therapists before commencing treatment. Assume all patients understand you even though they may not appear to. At a later stage, many patients describe conversations overheard between members of staff who were either talking about them or ignoring them in the early period. Remember a stroke is an event that happens suddenly; the previous day your patient could have been a director of a company, a highly skilled worker, or an independent active mother or grandmother. The change in situation can be frightening and a shock. If members of the family are present when you visit, they are also likely to be shocked and confused. Introduce yourself and say what you will be doing.

The emphasis during the early days is on ensuring normal respiratory function, skin care and management of mobility; initially this may comprise positioning or passive movements to ensure the maintenance of the length of soft tissue and range of movement, particularly when muscles work over more than one joint (Kilbride & Cassidy, 2009a). All people with stroke impairments after 24 hours should receive a full multidisciplinary assessment using an agreed procedure within five working days and this should be documented in the notes (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008).

Passive and active mobilizing can be assessed in the early stages in more than one position when the condition permits, for example lying, side lying and sitting. Through observation and handling during the process of moving the patient into the different positions, the physiotherapist will be able to judge the amount of impairment an individual has, their ability to control movement in particular head and trunk posture and their ability to initiate movement and to follow commands. Control of head and trunk position in the upright posture in the first few days is a positive indicator of future functional independence (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008).

Sub-acute stage

The sub-acute stage can start at any time between a few hours to days post stroke. People at this stage are medically stable having been assessed in a number of ways, which may include the use of brain scans, Glasgow coma scale, neurological signs, blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood gases, swallowing and glucose levels (Kilbride & Cassidy, 2009a). Intervention at this the stage is characterized by programmes of rehabilitation including physiotherapy. The emphasis is on determining progress through assessment and active participation in treatments. The first assessment is the baseline against which recovery or deterioration and the effectiveness of treatment can be measured.

Early supported discharge schemes are designed to reduce the amount of time people with stroke spend in hospital and provide the right environment for them to return home and a similar level of intensity of care as in a stroke unit. This approach is not suitable for everyone, but there is evidence to demonstrate cost and clinical effectiveness when organized by specialist stroke rehabilitation services (Early Supported Discharge Trialists, 2004; Langhorne et al., 2005). The meta-analysis by Langhorne and colleagues found that the greatest benefit was demonstrated in those trials evaluating multidisciplinary early supported discharge teams and in stroke patients with mild to moderate disability. The findings showed a reduction in long-term dependency and admission to institutional care as well as shortening hospital stays.

Stroke occurs at all ages but is predominantly a condition of the older population, although approximately one-quarter are aged less than 65 years (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008). Younger people with stroke will have different psychological and social needs to the average older person with stroke. Rehabilitation plans should be carefully negotiated with the individual. Many young people with stroke want to return to work and to indulge in leisure activities. Some barriers to these needs may be associated with fear and ignorance about stroke among the general public (Department of Health, 2007; Kersten et al., 2002).

Long-term stage

Although most recovery takes place in the first few months post stroke, improvements, adaptation and behavioural changes can continue for many years. The impact of a stroke lasts a lifetime and most people want to return to their previous roles and to be involved in their community (Ellis-Hill et al., 2009; Parker et al., 1997). There is evidence that coordinated community stroke teams prevent people from deteriorating once they are home and that targeted interventions can be effective (Walker et al., 2004). Recommendations in the National Stroke Strategy reinforce the importance of having a review system of health and social care needs and the integration of long-term rehabilitation in society through health and social support services (Department of Health, 2007).

A long-term role of rehabilitation services is to help individuals to identify the tasks that are important to them and to help them adjust and change their role and identity over time. At 12 months post stroke, individuals will begin to discover which of their valued activities they wish to resume (Robison et al., 2009). There is a need for a balance between maintaining hope for continued improvement and accepting limitations that may lead to a change in identity. A strong multidisciplinary team is required.

Discharge from hospital or therapy

For a person with stroke there are at least two critical points in the rehabilitation process where they experience a change in service delivery. The first happens when they leave hospital to return to live in the community, either at home or in a care home. The second point of transfer or discharge happens at the end of the physiotherapy programme. These stages in the life of a person with stroke are stressful and are often reported to be times of confusion by the individual and their carers. In the process of moving from being an inpatient to being an outpatient many people with stroke report feeling afraid, unsupported, forgotten and alone. Ellis-Hill et al. (2009) reported that, although patients found going home was important in their recovery, they were not prepared for continuing their recovery and life at home and highlighted poor communication, limited liaisons and a narrow focus of rehabilitation as barriers to success. They said that patients and families had their own ideas and expectations about recovery and discharge, and they said that these ideas change over time as patients and families face new situations. For successful rehabilitation, they recommended exploring each patient and family model, and suggest that improved communication and support would limit anxiety and fears and facilitate activity.

With specific respect to physiotherapy, patients are rarely prepared for the change from inpatient to outpatient. There are differences in the frequency of sessions and aims of treatment and people often feel abandoned (Wiles et al., 2004). They may not have been warned that a delay or waiting period can occur after they have left hospital and before treatment starts as an outpatient. In hospital, they may be seen daily or every other day by the physiotherapist who in the early stages, will work to maximize recovery. In the community, treatment sessions may be booked only once or twice a week and the aim of therapy may change to an emphasis on working for function. Preparation for these changes in service is important and communication should take place between the person with stroke and their carers, and between staff in the different settings.

Communication is also essential at the second point of discharge; the end of the treatment programme. The stopping of treatment must be planned, structured and communicated over time. The literature suggests that explicit discussions between physiotherapists and patients about the anticipated extent of recovery tends to be avoided during physiotherapy, making discharge from therapy difficult, and this is the point when differing expectations might be expected to be confronted (Wiles et al., 2004). Patients believe physiotherapy is effective but disappointment with the extent of recovery reached at point of discharge is likely to be linked to expectations of recovery. The result of over-optimistic expectations about recovery is a feeling of distress and abandonment when physiotherapy ends (Wiles et al., 2002). There is evidence that patients and their carers want a clear and honest appraisal of their condition and information about likely recovery. Physiotherapists need to be aware that even if they work to actively avoid raising expectations for recovery, patients will maintain high expectations of outcome of treatment. The challenge to physiotherapists is to find ways of encouraging realistic expectations of treatment without destroying the process of active rehabilitation and skill acquisition. The discharge experience could be improved by health-care professionals understanding and exploring patients’ individual models of recovery. This would allow professionals to (a) access patients concerns, (b) develop programmes addressing these, (c) correct misinterpretations, (d) keep people fully informed, and (e) share and validate the experience to reduce their sense of isolation (Ellis-Hill et al., 2009). At this point, the individual should be provided with clear instructions on how to contact services for reassessment and ensure continuing support for health maintenance is provided if required. They should be informed about the events that might require further contact (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008). Physiotherapists should ensure that individuals know the details of their self-practice programme and that they are reminded that this means their treatment is on-going; they should also be told if there is automatic access to on-going review and where appropriate further physiotherapy.

Physical management

Setting

Somewhere between 5% and 15% of people with stroke are discharged into residential care or nursing homes. These people with stroke rarely receive any rehabilitation (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008).

Core principles

The role of the physiotherapist is to enable people with stroke to achieve their optimal physical potential and functional independence. The process comprises the use of techniques to facilitate the relearning of movements, use of strategies to enhance adaptation, the prevention of secondary complications, and the maintenance of ability and function (Lennon & Bassile, 2009). The re-learning or restorative process is predominantly educational and reliant on active participation by the person with stroke. The treatment demands effort from the patient and the quality of the rehabilitation process is reliant on the quality of the working partnership between the physiotherapist and the person with stroke. The skill of the physiotherapist is in understanding the movement problem and responding appropriately to the responses of the patient to the therapeutic intervention, i.e. handling, positioning, facilitating activity and practice. The physiotherapist must learn to judge the abilities and disabilities of the person with stroke and monitor fluctuations in motor control and tone as a consequence of recovery, independence and treatment. In the early stages, she/he must watch for changes in medical stability and at all stages she/he needs to be aware of risks to safety while being able to identify how much the patient can do independent of help.

Problem-solving approach

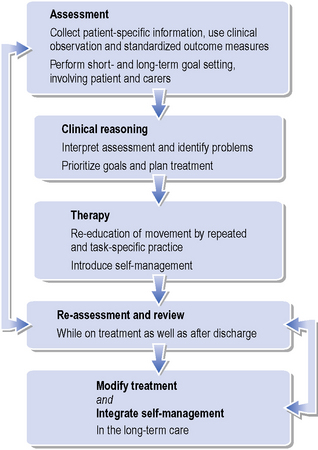

The problem-solving approach to treatment creates an evolving structure for planning an individual’s management (Figure 2.4). Information gathered from the assessments is used to set short- and long-term treatment goals. Patients and carers should be given an explanation of the movement problems and then together with the physiotherapist agree on joint treatment goals, which are documented for communication with the wider team. Assessment of the effects of intervention during and after treatment sessions allows for the adjustment of treatment, and then further assessment and modification of goal setting. A pattern of regular re-assessments during treatment should ensure the monitoring of change or lack of change in the physical status of a patient over time. In addition to the cycle of re-assessments, the use of reflection on practice and the patient’s response to treatment will ensure the on-going development of the treatment package.

Figure 2.4 Proposed structure for problem-solving approach of physical management of people after stroke

2. Clinical reasoning and treatment planning

Clinical decisions are built on the basis of information gathered. Clinical hypotheses for explaining movement deficits or functional difficulties are stated and used to prioritize goals and planning of treatment. For example, weakness in the trunk or the hip muscles may explain the inability to balance and perform washing and dressing in sitting (Kilbride & Cassidy, 2009b).

3. Therapy

General therapy principles

To maximize movement retraining, the person who is learning needs to have a clear understanding of what she/he is expected to do and what she/he is aiming to achieve. Clear instructions are essential, but it is even more important to check that the patient understands what is required. Knowledge of performance is also paramount in the learning process and comes from internal sensory feedback, but if after stroke the sensory system has been damaged, the patient will rely more heavily on verbal guidance and instruction from the physiotherapist (Schmidt, 1991). Positive reinforcement by the physiotherapist of corrected movements will assist in achieving the targeted goal. Repeated and task-specific practice has been shown to be the most effective feature of movement re-training. Recommendations in the Stroke Guidelines (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008) are that patients should undergo as much therapy as they are able to tolerate in the early stages and a minimum of 45 minutes. Practice of their new skills should be encouraged by the whole team with performance in different settings and task-specific training should be used to improve mobility such as standing up and sitting down, and gait speed and gait endurance (French et al., 2004). A review of 151 clinical trials by Van Peppen and colleagues (2004) found small to large effect sizes for task-orientated exercise training, particularly when applied intensively and early after stroke onset. In contrast, when therapy for impairments was observed, improvements were shown but they did not generalize to function.

Early physiotherapy

Evidence-based physiotherapy in the early stages post stroke emphasizes the importance of maintaining optimal posture, range of movement and the return of balance control. When the person with stroke has limited movement and no independent sitting balance, treatment should emphasize optimal positioning in lying and sitting in order to minimize the risk of respiratory complications, shoulder pain, contractures and pressure sores (Tyson & Nightingale, 2004). Splinting (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008), passive movements and stretching help to maintain range of movement and can be taught to carers, patients and staff. Loss of, or limited balance control is common after stroke (due to reduced limb and trunk movements, sensation and spatial perceptual disturbance) but intensive progressive balance training in sitting and standing is important (Marigold et al., 2005; Verheyden et al., 2009) and should begin in the early stages when patients are medically stable. The return of balance control in sitting is a strong positive indicator for future function (Verheyden et al., 2007). Always check the symmetry of posture in sitting and standing and the position of the head. Abnormal head postures can be linked to visuospatial neglect, loss of attention and lack of confidence and fatigue. Greater challenges to balance can be introduced by changing the posture and increasing the complexity of movement. Normal movements (pattern of coordination and sequencing of components) provide a valuable guideline for identifying abnormalities among people with stroke.

Physiotherapy for locomotor and upper limb recovery

When movement and activity in the limbs is more evident, therapy should follow repetitive, task-specific training particularly for ‘standing up and sitting down’ and for gait (French et al., 2007). The emphasis should be on repetitive practice with specialist guidance. Patients who have some ability to walk independently in the first few months may benefit from partial body-weight supported treadmill training, but this is not appropriate for everyone. Patients should be assessed and taught how to use walking aids and ankle-foot orthosis for footdrop and they should be individually fitted (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008). Opportunities to practice mobilizing inside and outside should be made widely available. Strength training should also be included both to improve selected muscles and gait speed and endurance (Ada et al., 2006; Morris et al., 2004). There is no evidence to support the fears that resisted exercises worsen increase in tone (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008). Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) should not be recommended on a routine basis and should only be prescribed by specialist teams familiar with its use and evaluation (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008; Robbins et al., 2006). In patients where there is some arm movement, repetition of practice should be encouraged. Constraint-induced therapy is inappropriate for most people. For this therapy, individuals need some finger extension, be able to walk, be at least 2 weeks post stroke and be committed to the rigours of the regime. Finally, all patients should be given some training in self-management skills and problem solving (Kendall et al., 2007).

Fitness and aerobic training should be considered for people with stroke who have some independence of mobility (see Ch. 18). Many of the previously considered activities can also be progressed as recovery takes place through increased complexity of tasks, whole-body movements and increased repetitions. All progressions need to be considered within the context of the person’s ability to move, to learn and their functional independence and safety.

5. Modify treatment and integrate self-management

As part of the treatment programme and considering the long-term care of people after stroke, physiotherapists should ensure that they modify treatment and have provided their patients with a list of self-practice activities, which may or may not involve carer input (see Ch. 19). If carers are to be recruited to the task they should be taught what to do as they may play a crucial part in assisting with self-practice sessions. The activities should be monitored by the physiotherapist over time and regular re-assessment and review should take place in order to optimize long-term service delivery.

General management issues

Respiratory care

The aim of physiotherapy for respiratory care in the overall management of stroke is to maintain a clear airway, stimulate a cough reflex and assist with removal of secretions (see Ch. 15). Respiratory problems are most likely to occur in the acute and sub-acute stages. Patients may arrive with a chest infection or may be infected during their hospital stay. People with stroke may be more predisposed to these difficulties due to the considerable reduction in their mobility, the greater likelihood of supine positioning, stroke severity and difficulties with swallowing which may lead to aspiration. Positioning of patients may help with optimal oxygen saturation (Tyson & Nightingale, 2004).

Visual impairments

Visual impairments following stroke are wide ranging and encompass low vision (age-related deteriorating vision), eye movement and visual-field abnormalities and visual-perceptual difficulties (Rowe et al., 2009). Reports have indicated that a high proportion of these visual problems have frequently been unrecognized (Pollock, 2000) despite the disabling impact. Visual impairments can influence the way people with stroke perform everyday functional activities and place them at risk of falls. Individuals should be assessed by a specialist for visual impairments.

Neuropathic pain

Pain can be generated following damage to neural tissues (neuropathic pain). Estimates vary from 5 to 20%, but those who are sufferer find it extremely unpleasant. This type of pain may be associated with sensory loss and tone abnormalities. If the pain cannot be controlled pharmaceutically it may be necessary to refer individuals for specialist pain management (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008).

Fatigue

Fatigue after stroke is common (Staub & Bogousslavsky, 2001) and may limit a patient’s tolerance of rehabilitation sessions (Morley et al., 2005). The cause of fatigue is unknown but a link with physical de-conditioning is a possible explanation, although this has not been proven. Further research into the aetiology and management is needed but with current knowledge physiotherapists need to ensure people with stroke have adequate rests during rehabilitation. Care is also needed to ensure individuals are taking sufficient nutrition.

Communication problems and swallowing disorders

These are predominantly assessed and managed by speech and language therapists. Physiotherapists working with people with stroke who experience communication difficulties must consult their colleagues for advice on developing management strategies. These deficits are distressing and can have a major impact on the re-education of movement and physical independence. When teaching or relearning any new skill it is important to establish a partnership between the teacher (physiotherapist) and the student (patient). Knowledge of the level of accuracy of understanding and response is important. A clear and consistent approach to communication is usually helpful. Remember to greet people and to involve them in the rehabilitation process. People need to be given extra time to respond and any questions or commands should be simple. Communication aids may be required. Studies have shown that people who have communication difficulties are more likely to be isolated and are not consulted about their care (Gordon et al., 2009). Communication problems commonly associated with stroke are:

Approximately half of people following stroke will have swallowing difficulties or dysphagia (Smithard et al., 1997). The main swallowing difficulties of approximately one-third will have been resolved in the first 7 days. A specialist swallowing assessment should be carried out within the first 72 hours. Physiotherapists may be asked to provide help and guidance with upright posture during feeding or facilitate facial movements. Physiotherapists should be aware of the impact of restricted nutrition and hydration on energy levels and physical activity. Sometimes patients are fed through a nasogastric tube (NGT) or via a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube (PEG).

Cognitive problems

Many patients in the early stages following stroke are likely to have some cognitive loss. Poor levels of alertness are common in the first few days and more so with right hemisphere lesions (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008). Patients not progressing as expected should be referred for detailed cognitive assessment. Hyndman and colleagues (2008) demonstrated that attention deficits persist a long time after the initial onset of stroke. Difficulties with reduced attention span will affect physiotherapy intervention because the ability to attend is a prerequisite for learning. It may be necessary for the physiotherapist to keep treatment sessions short with rests and to minimize background distraction (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008). A physiotherapist should work with the psychologist to develop strategies for teaching compensation (see Ch. 17). Impaired expressive language performance and the presence of attention deficits have been reported to be associated with a higher risk of cognitive decline (Ballard et al., 2003). Reduced memory following stroke is also common and can be linked to difficulty with learning. Individuals should be formally assessed and again taught compensatory strategies in a familiar environment.

Spatial and perceptual problems

People who have had a right-sided stroke, and therefore a left hemiplegia, have the most severe perceptual problems. With visuospatial neglect, patients fail to respond to stimuli presented on the hemiplegic side and any patient with such a suspected impairment should be assessed with a test battery such as the Behavioural Inattention Test (Wilson et al., 1987). Any patient with impaired attention should be encouraged to draw attention to that side (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008). Agnosia is the difficulty in recognizing for instance objects, people or sounds with your senses (Kandel et al., 2000). If this condition is suspected, a formal assessment by a psychologist or occupational therapist should be requested (see Ch. 17). Patients who deny or disown their affected limbs should be encouraged to observe their limbs and the impairment should be explained to them and their family.

Dyspraxia

Dyspraxia is the difficulty in executing purposeful movements on demand despite adequate limb movements and sensation. The difficulty may be most apparent with functional tasks such as making a drink or getting dressed (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008; Smania et al., 2006). Formal assessment and teaching strategies for compensation (e.g. dividing up a larger task in clearly defined smaller tasks) is recommended.

Psychosocial issues

Mood disturbance is commonly manifested as depression or anxiety; the severity is frequently associated with severity of cognitive and motor impairments and the amount of restricted activities. In addition, existing psychological problems may also impact on the rehabilitation process. People who are depressed may suffer from fatigue and lack of attention, both of which have a negative effect on learning (see Ch. 17).

Emotional lability is common after a stroke (House et al., 1991). Individuals experience outbursts of crying or laughing inappropriately. Expert guidance should be sought, but at all times the physiotherapist should approach the problem with tact and care.

The return to valued activities and participation in community life is significantly disrupted post stroke and research increasingly indicates that social factors such as perceived stigma might contribute to people’s reluctance to leave the house and mix with the community. Stroke has been found to significantly affect people’s wellbeing and quality of life (Secrest & Thomas, 1999). Physical disabilities account for some of the problems as mobility remains a major concern for people (Ellis-Hill et al., 2009), but fear and attitudes of the general public may add to the barriers to integration.

Carer support

The word carers can be used for formal paid carers and informal unpaid carers. At all times the patient’s view on the involvement of their family and other carers should be sought (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008). With the patient’s agreement, carers can provide additional information, and additional help with treatment practice and everyday tasks.

Secondary complications

Soft-tissue damage

Soft-tissue problems may involve skin breakdown and reduced range of movement, which can lead to joint contractures. Severely reduced levels of mobility following a stroke and restricted postures in bed and the chair can lead to pressure sores and soft-tissue shortening. The physiotherapist can help to prevent these secondary complications by regularly assisting people with stroke to vary their postures and positions in lying, side lying and when sitting out in a chair. Also the physiotherapist should work to ensure full range of movement at all joints of the affected limbs, but in particular shoulder, ankle, knee and extending those muscles crossing two joints (Kilbride & Cassidy, 2009b; also see Ch. 14).

Shoulder pain

The weak, affected arm of people with stroke is at risk of damage during the acute and sub-acute stages. While 5% of the stroke community is reported as having persistent pain, many more may have pain at different stages; this is often associated with an initial subluxation at the shoulder and later spasticity in the upper limb (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008). Physiotherapists should always carefully assess an affected arm and monitor for pain. Overhead arm slings should be avoided, and staff and carers should be trained in carefully handling the arm and in correct positioning of the limb. In addition, the lack of movement and muscle activity, and the downward hanging of the arm in the upright posture can lead to swelling of the hand.

Falls

Falls amongst the stroke population are common and have been reported to affect as many as 50 to 70% of those with stroke living in the community (Hyndman et al., 2002). The percentage varies according to the stage of recovery with more in the 6-month period after discharge from hospital. Factors such as inability to walk, visuospatial deficits, apraxia, use of sedatives and greater body sway (Andersson et al., 2006) have been associated with falls in the acute stage. At the point of leaving hospital, those who have upper limb impairment and have experienced near-falls in hospital are at greater risk of falls in the community (Ashburn et al., 2008). In the sub-acute and long-term stages, the association is not with specific stroke impairments but with reduced mobility and balance problems, particularly while performing complex tasks such as dressing (Lamb, 2003). See Chapter 20 for more information about falls and their prevention.

Multidisciplinary team

In the last few years, specialist stroke services have been seen as a priority throughout the UK and they have been shown to be more cost and clinically effective if they are well organized with specialist staff. Health-care providers with expert knowledge of managing people with stroke are recommended for the multidisciplinary teams. Teams may work in acute or rehabilitation stroke units or settings or in the primary care trust. The range of disciplines represented in a team reflects the range of impairments that can emerge following a stroke. People with a suspected stroke should be seen by a specialized physician for diagnosis and be managed by staff with expertise in stroke and rehabilitation (Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke, 2008). A team typically includes: consultant physician(s), nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, psychologists, dieticians and social workers. Stroke teams should meet at least once a week to agree on the management of patient problems and documentation of the plan and assessments to be completed. There should be education and specialist training programmes with access to services such as provision of assistive devices. The person with stroke and their carers are also part of the team and should be involved and consulted in the process of identifying and solving problems and setting treatment goals.

Case study

Presenting history

After 1 week

After 1 month

After 3 months

After 6 months

Ada L., Dorsch S., Canning C. Strengthening interventions increase strength and improve activity after stroke: a systematic review. Aust. J. Physiother.. 2006;5:241-248.

Amarenco P., Bogousslavsky J., Caplan L.R., Donnan G.A., Hennerici M.G. Classification of stroke subtypes. Cerebrovas. Dis.. 2009;27:493-501.

Andersson A.G., Kamwendo K., Seiger A., Appelros P. How to identify potential fallers in a stroke unit: validity indexes of four test methods. J. Rehabil. Med.. 2006;38:186-191.

Ashburn A., Hyndman D., Pickering R., et al. Predicting people with stroke at risk of falls. Age Ageing. 2008;37:270-276.

Ballard C., Rowan E., Stephens S., et al. Prospective follow-up study between 3 and 15 months after stroke: improvements and decline in cognitive function among dementia-free stroke survivors 75 years of age. Stroke. 2003;34:2440-2444.

Bamford J., Sandercock P., Dennis M., et al. Classification and natural history of clinically identifiable subtypes of cerebral infarction. Lancet. 1991;337:1521-1526.

Berg K., Wood-Dauphinee S., Williams J.I. The Balance Scale: reliability assessment with elderly residents and patients with an acute stroke. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med.. 1995;27:27-36.

Chalela J., Kidwell C., Nentwich L., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: a prospective comparison. Lancet. 2007;369:293-298.

Collin C., Wade D.T., Davies S., Horne V. The Barthel ADL Index: A reliability study. Int. J. Disabil. Stud.. 1988;10:61-63.

Collin C., Wade D. Assessing motor impairment after stroke: A pilot reliability study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1990;53:576-579.

Demain S., Wiles R., Roberts L., McPherson K. Recovery plateau following stroke: Fact or fiction. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2006;28:815-821.

Demeurisse G., Demol O., Robaye E. Motor evaluation in vascular hemiplegia. Eur. J. Neurol.. 1980;19:382-389.

Department of Health. A new ambition for Stroke – a consultation on a national strategy. London: Department of Health, 2007.

DeSouza L.H., Langton-Hewer R., Miller S. Assessment of recovery of arm control in hemiplegic stroke patients. Arm function test. Int. J. Rehabil. Med.. 1980;2:3-9.

Dubinsky R., Lai S.M. Mortality of stroke patients treated with thrombolysis: analysis of nationwide inpatient sample. Neurology. 2006;66:1742-1744.

Duncan P., Weiner D., Chandler J. Functional reach: a new clinical measure of balance. J. Gerontol.. 1990;45:M192-M197.

Early Supported Discharge Trialists. Services for reducing duration of hospital care for acute stroke. In: Cochrane Library. Chichester: J Wiley & Son Ltd; 2004. Issue 1

Ellis-Hill C., Robison J., Wiles R., et al. Going home to get on with life: Patients and carers experiences of being discharged from hospital following stroke. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2009;31:61-72.

Flint A.C., Duckwiler G.R., Budzik R.F., et al. Mechanical thrombectomy of intracranial internal carotid occlusion: pooled results of the MERCI and multi MERCI part I trials. Stroke. 2007;38:1274-1280.

French B., Thomas L., Leathley M., et al. Repetitive task training for improving functional ability after stroke: a systematic review. Cochrane Database Sys. Rev.. 4, 2007. CD006073

Ginsberg M.D. Neuroprotection for ischemic stroke: past, present and future. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:363-389.

Gordon C., Ellis-Hill C., Ashburn A. The use of conversational analysis: exploring the processes underlying nurse-patient interaction in communication disability following a stroke. J. Adv. Nurs.. 2009;65:544-553.

Heller A., Wade D.T., Wood V.A., et al. Arm function after stroke: Measurement and recovery over the first three months. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1987;50:714-719.

Hendricks H.T., van Limbeek J., Geurts A.C., Zwarts M.J. Motor recovery after stroke: A systematic review of the literature. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.. 2002;83:1629-1637.

Hill K.D., Bernhardt J., McGann A.M., et al. A new test of dynamic standing balance for stroke patients: reliability, validity and comparison with healthy elderly. Physiother. Can.. 1996;48:257-262.

Holden M.K., Gill K.M., Magliozzi M.R., et al. Clinical gait assessment in the neurologically impaired. Reliability and meaningfulness. Phys. Ther.. 1984;64:35-40.

Holden M.K., Gill K.M., Magliozzi M.R. Gait assessment for neurologically impaired patients. Standards for outcome assessment. Phys. Ther.. 1986;66:1530-1539.

House A., Dennis M., Morgridge L., et al. Mood disorders in the year after first stroke. Br. J. Psychiatry. 1991;158:83-92.

Hyndman D., Ashburn A., Stack E. Fall events among people with stroke living in the community: circumstances of falls and characteristics of fallers. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.. 2002;83:165-170.

Hyndman D., Pickering R., Ashburn A. The influence of attention deficits on functional recovery post stroke during the first 12 months after discharge from hospital. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2008;79:656-663.

Intercollegiate Working Party for Stroke. National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke, third ed. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2008.

Kandel E.R., Schwartz J.H., Jessel T.M. Essentials of Neural Science and Behaviour. New York: Appleton & Lange, 2000.

Kendall E., Catalano T., Kuipers P., et al. Recovery following stroke: the role self-management education. Soc. Sci. Med.. 2007;64:735-746.

Kersten P., Low J., Ashburn A., et al. The unmet needs of young people who have had a stroke: results of a national survey. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2002;24:860-866.

Kilbride C., Cassidy E. The acute patient before and during stabilisation: stroke, TBI and GBS. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2009. (Chapter 10.2)

Kilbride C., Cassidy E. The stable acute patient with potential for recovery: stroke, TBI and GBS. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2009. (Chapter 10.1)

Kwakkel G., Wagenaar R.C., Kollen B.J., Lankhorst G.J. Predicting disability in stroke – a critical review of the literature. Age Ageing. 1996;25:479-489.

Kwakkel G., Kollen B.J., Van der Grond J., Prevo A.J. Probability of regaining dexterity in the flaccid upper limb: Impact of severity of paresis and time since onset in acute stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:2181-2186.

Lamb S.E., Ferrucci L., Volapto S., et al. For women’s health & ageing study. Risk factors for falling in home-dwelling older women with stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:494-500.

Langhorne P., Taylor G., Murray G., et al. Early supported discharge services for stroke patients: a meta-analysis of individual patients’ data. Lancet. 2005;365:455-456.

Lennon S., Bassile C. Guiding principles for neurological physiotherapy. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2009. (Chapter 8)

Mahoney F., Barthel D. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md. State Med. J.. 1965;14:61-65.

Marigold D.S., Eng J., Dawson A., et al. Exercise leads to faster postural reflexes, improved balance and mobility and fewer falls in older persons with chronic stroke. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc.. 2005;53:416-423.

Meijer R., Ihnenfeldt D.S., de Groot I.J., et al. Prognostic factors for ambulation and activities of daily living in the subacute phase after stroke. A systematic review of the literature. Clin. Rehabil.. 2003;17:119-129.

Morley W., Jackson K., Mead G. Fatigue after stroke: neglected but important. Age Ageing. 2005;34:313.

Morris S., Dodd K., Morris M. Outcomes of progressive resistance strength training following stroke: A systematic review. Clin. Rehabil.. 2004;18:27-39.

Parker C.J., Gladman J.R., Drummond A.E. The role of leisure in stroke rehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil.. 1997;19:1-5.

Pollock L. Managing patients with visual symptoms of cerebrovascular disease. Eye News. 2000;7:23-26.

Robbins S., Houghton P., Woodbury M., Brown J. The therapeutic effect of functional and transcutaneous electric stimulation on improving gait speed in stroke patients: a meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil.. 2006;87:853-859.

Robison J., Wiles R., Ellis-Hill C., et al. Resuming previously valued activities post-stroke: who or what helps? Disabil. Rehabil.. 2009;31:1555-1566.

Rowe F., Brand D., Jackson C., et al. Visual impairment following stroke: do stroke patients require vision assessment? Age Ageing. 2009;38:188-193.

Saver J.L. Time is brain – quantified. Stroke. 2006;37:263-266.

Schmidt R.A. Motor learning principles for physical therapy. Lister M.J., editor. Contemporary management of motor control problems. Proceedings of the II Step Conference. USA Foundation for Physical Therapy. 1991:49-63.

Secrest J., Thomas S. Continuity and discontinuity: the quality of life following stroke. Rehabil. Nurs.. 1999;24:240-246.

Smania N., Aglioti S.M., Girardi F., Tinazzi M., Fiaschi A., Cosentino A., et al. Rehabilitation of limb apraxia improves daily life activities in patients with stroke. Neurology. 2006;67:2050-2052.

Smithard D.G., O’Neill P., England R., et al. The natural history of dysphagia following stroke. Dysphagia. 1997;12:188-193.

Staub F., Bogousslavsky J. Fatigue after stroke: a major but neglected issue. Cerebrovasc. Dis.. 2001;12:75-81.

Stokes E.K. Outcome measurement. In: Lennon S., Stokes M., editors. Pocketbook of Neurological Physiotherapy. Churchill Livingstone; 2009:192-201.

Sunderland A., Tinson D., Bradley L., Hewer R.L. Arm function after stroke. An evaluation of grip strength as a measure of recovery and a prognostic indicator. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1989;52:1267-1272.

The European cooperative acute stroke study (ECASS). Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2008;359:1317-1329.

The National Institute of Neurological Sisorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The national institute of neurological disorders and stroke rt-PA stroke study group. N. Engl. J. Med.. 1995;333:1581-1587.

The Stroke Association. http://www.stroke.org.uk/information/did_you_know.html. (accessed 27.01.10)

Tyson S.F., Connell L.A. How to measure balance in clinical practice. A systematic review of the psychometrics and clinical utility of measures of balance activity for neurological conditions. Clin. Rehabil.. 2009. Aug 5, Epub ahead of print

Tyson S.F., DeSouza L.H. Development of the Brunel Balance Assessment: a new measure of balance disability post stroke. Clin. Rehabil.. 2004;18:801-810.

Tyson S.F., DeSouza L.H. Reliability and validity of functional balance tests post stroke. Clin. Rehabil.. 2004;18:916-923.

Tyson S.F., Nightingale P. The effects of positioning on oxygen saturation in acute stroke: a systematic review. Clin. Rehabil.. 2004;18:863-871.

Van de Port I., Kwakkel G., van Wijk I., Lindeman E. Susceptibility to deterioration of mobility long-term after stroke: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2006;37:167-171.

Van Peppen R.P.S., Kwakkel G., Wood-Dauphinee S., et al. The impact of physical therapy on functional outcomes after stroke: what’s the evidence? Clin. Rehabil.. 2004;18:833-862.

Van Peppen R.P.S., Hendriks H.J.M., Van Meeteren N.L.U., et al. The development of a clinical practice stroke guideline for physiotherapists in The Netherlands: A systematic review of available evidence. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2007;10:767-783.

Verheyden G., Nieuwboer A., Mertin J., et al. The Trunk Impairment Scale: a new tool to measure motor impairment of the trunk after stroke. Clin. Rehabil.. 2004;18:326-334.

Verheyden G., Nieuwboer A., De Wit L., et al. Trunk performance after stroke: an eye catching predictor of functional outcome after stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2007;78:694-698.

Verheyden G., Nieuwboer A., De Wit L., et al. Time course of trunk, arm, leg, and functional recovery after ischemic stroke. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2008;22:173-179.

Verheyden G., Vereeck L., Truijen S., et al. Additional exercises improve trunk performance after stroke: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2009;23:281-286.

Wade D.T. Measurement in neurological rehabilitation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Walker M., Leonardi-Bee J., Bath P., et al. An individual patient meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of community occupational therapy for stroke patients. Stroke. 2004;35:2226-2232.

Warlow C.P. Epidemiology of stroke. Lancet. 1998;352(Suppl. 3):1-4.

WHO. ICF-introduction, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. 2001. Geneva http://www.who.int/classification/icf/intros/ICF-ENG-Intro.pdf

WHO MONICA project principal investigators. The world health organization MONICA project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular diseases: a major international collaboration). J. Clin. Epidemiol.. 1988;41:105-114.

Wiles R., Ashburn A., Payne S., Murphy C. Patients’ expectations of recovery following stroke: a qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil.. 2002;24:841-850.

Wiles R., Ashburn A., Payne S., Murphy C. Discharge from physiotherapy following stroke: the management of disappointment. Soc. Sci. Med.. 2004;59:1263-1273.

Wilson B., Cockburn J., Halligan P. The Behavioural Inattention Test. Titchfield: Thames Valley Test Company, 1987.