Chapter 16 Strength, Power, and Endurance Training

OVERVIEW.

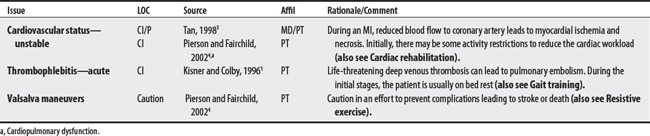

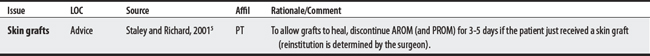

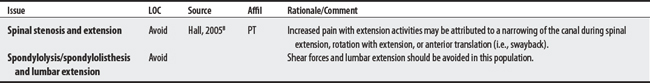

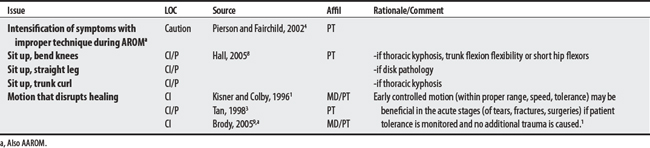

Active range of motion (AROM, also active assisted range of motion [AAROM]) is movement generated by active muscle contraction and produced within the unrestricted portion of a joint. In active-assisted range of motion, manual or mechanical assistance is provided by an outside force to assist the prime mover through the available joint range.1,2 AROM concerns generally relate to acute cardiac or vascular conditions, stress to unstable or still fragile musculoskeletal or skin tissue (e.g., postop, injuries), or activities that further compromise a structure (e.g., spinal stenosis) (also see ROM assessment).

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND PRECAUTIONS

I00-I99 DISEASES OF THE CIRCULATORY SYSTEM

L00-L99 DISEASES OF THE SKIN AND SUBCUTANEOUS TISSUE

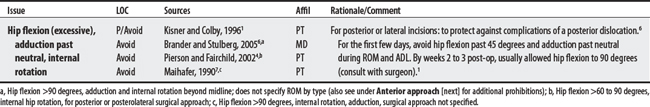

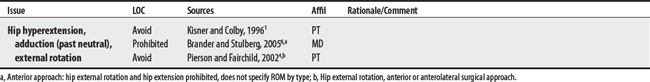

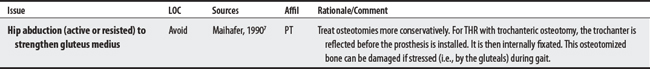

M00-M99 DISEASES OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE

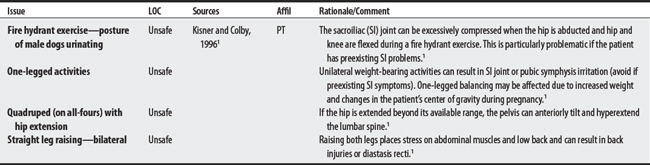

O00-O99 PREGNANCY, CHILDBIRTH, AND PUERPERIUM

R00-R99 SYMPTOMS, SIGNS INVOLVING THE SYSTEM

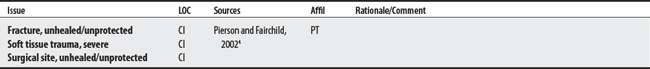

S00-T98 INJURY, POISONING, AND CERTAIN OTHER CONSEQUENCES OF EXTERNAL CAUSES

1 Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1996.

2 Bottomley JM. Quick reference dictionary for physical therapy. Thorofare (NJ): Slack, 2000.

3 Tan JC. Practical manual of physical medicine and rehabilitation: diagnostics, therapeutics, and basic problems. St Louis: Mosby, 1998.

4 Pierson FM, Fairchild SL. Principles and techniques of patient care, ed 3. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002.

5 Staley M, Serghiou M. Casting guidelines, tips and techniques: proceedings from the 1977 American Burn Association PT/OT Casting Workshop. J Burn Care Rehab. 1998;19(3):254-260.

6 Brander VA, Stulberg SD. Rehabilitation after lower limb joint reconstruction. Delisa JA, editor. Physical medicine and rehabilitation: Principles and practices, vol 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

7 Maihafer GC. Rehabilitation of total hip replacements and fracture management considerations. In: Echternach JL, editor. Physical therapy of the hip. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1990.

8 Hall C. Therapeutic exercise for the lumbopelvic region. In: Hall CM, Brody LT, editors. Therapeutic exercise: moving toward function. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

9 Brody LT. Impaired joint mobility and range of motion. In: Hall CM, Brody LT, editors. Therapeutic exercise: moving toward function. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

16.2 Closed Chain Exercise

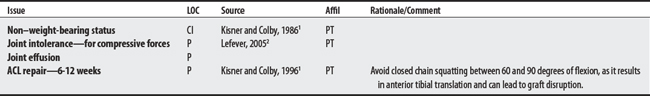

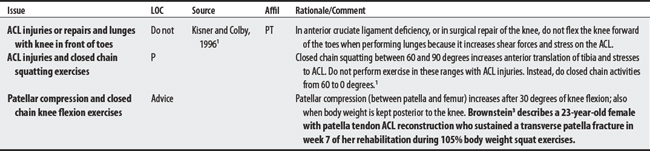

Closed chain (CC) exercises involve activities where an individual’s proximal body part moves over his or her fixed (i.e., stabilized) distal segment. An example is performing an upper extremity push-up.1 There is some concern for stressing joints, particularly at the knee, while performing squats (a closed chain activity) at certain angles following ACL injuries or repairs.

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND PRECAUTIONS

M00-M99 DISEASES OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE

R00-R99 SYMPTOMS, SIGNS, AND ABNORMAL CLINICAL AND LABORATORY FINDINGS (NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED)

S00-T98 INJURY, POISONING, AND CERTAIN OTHER CONSEQUENCES OF EXTERNAL CAUSES

1 Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1996.

2 Lefever SL. Closed kinetic chain training. In: Hall CM, Brody LT, editors. Therapeutic exercise: moving toward function. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

3 Brownstein B, Brunner S. Patella fractures associated with accelerated ACL rehabilitation in patients with autogenous patella tendon reconstruction. J Orthopaed Sports Phys Ther. 1997;26(3):168-172.

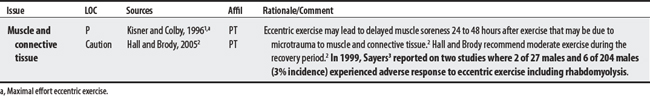

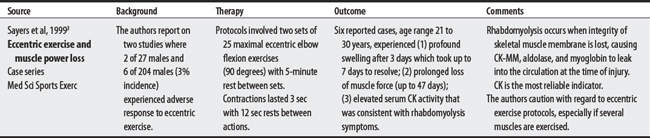

16.3 Eccentric Exercise

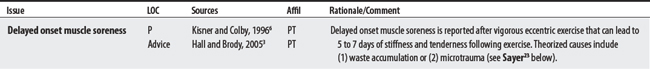

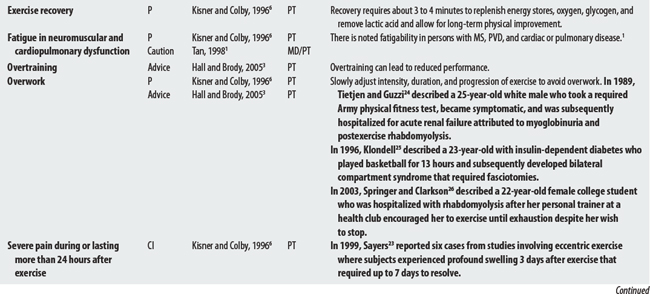

Eccentric exercise is a form of dynamic resistive exercise that involves tension development while the muscle is lengthening.1 Familiar functions involving eccentric activity of the lower limbs include sitting down or descending stairs. Sources identify delayed muscle soreness from microtrauma as a concern following eccentric work.1,2 In more severe cases, rhabdomyolysis may occur.3

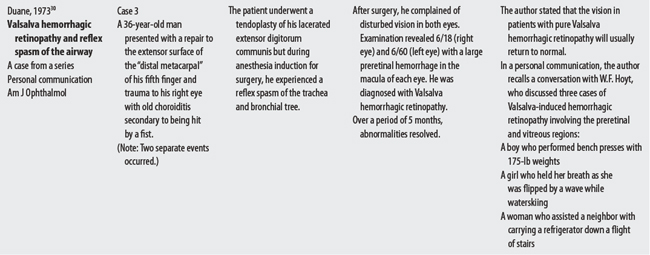

1 Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1996.

2 Hall CM, Brody LT. Impairment in muscle performance. In: Hall CM, Brody LT, editors. Therapeutic exercise: moving toward function. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

3 Sayers SP, Clarkson PM, Rouzier PA, Kamen G. Adverse events associated with eccentric exercise protocols: six case studies. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(12):1697-1702.

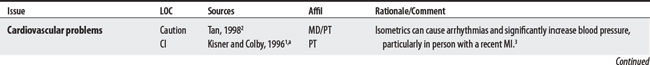

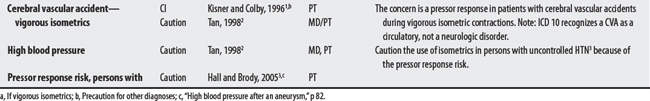

16.4 Isometric Exercise

Isometric exercise is a static form of exercise whereby tension develops in the muscle but there is essentially no joint movement. The length of the muscle remains unchanged during the contraction. Three sources identify four cardiovascular concerns for isometric exercise that primarily center around the pressor (increased blood pressure) response (also see Resistive exercise).

I00-I99 DISEASES OF THE CIRCULATORY SYSTEM

1 Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1996.

2 Tan JC. Practical manual of physical medicine and rehabilitation: diagnostics, therapeutics, and basic problems. St Louis: Mosby, 1998.

3 Hall CM, Brody LT. Impairment in muscle performance. In: Hall CM, Brody LT, editors. Therapeutic exercise: moving toward function. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

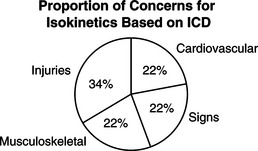

16.5 Isokinetic Exercise

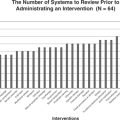

Isokinetic exercise is a form of resistive exercise in which a rate-limiting device controls the movement speed of the joint.1 The device is used both for strength testing and exercise. Two sources identified nine concerns for isokinetic exercise, with the largest proportion related to unhealed injuries. Joint and bone instability was a shared concern (see Isokinetic testing, Exercise equipment for complications; also see Resistive exercise).

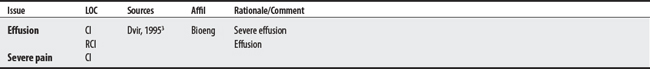

I00-I99 DISEASES OF THE CIRCULATORY SYSTEM

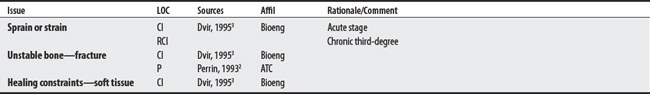

M00-M99 DISEASES OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE

R00-R99 SYMPTOMS, SIGNS INVOLVING THE SYSTEM

S00-T98 INJURY, POISONING, AND CERTAIN OTHER CONSEQUENCES OF EXTERNAL CAUSES

1 Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1996.

2 Perrin DH. Isokinetic exercise and assessment. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics, 1993.

3 Dvir Z. Isokinetics: muscle testing, interpretation, and clinical applications. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1995.

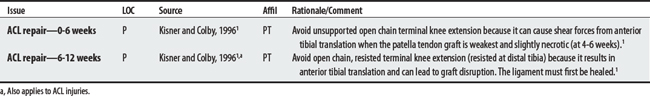

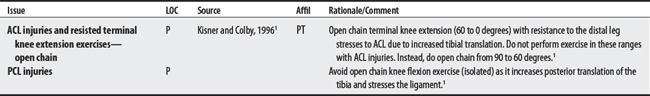

16.6 Open Chain Exercise

Open chain exercise is performed with the distal body part moving freely in space. Examples include cane exercises for the upper extremities or knee extension exercises while sitting for the lower extremities. One source lists several concerns related to stressing cruciate tissue with cruciate ligament injuries or repairs during open chain knee exercises (also see Closed chain exercise).

M00-M99 DISEASES OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE SYSTEM

S00-T98 INJURY, POISONING, AND CERTAIN OTHER CONSEQUENCES OF EXTERNAL CAUSES

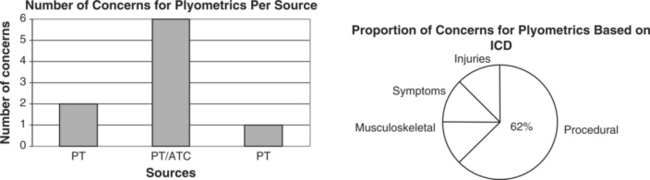

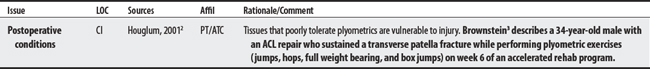

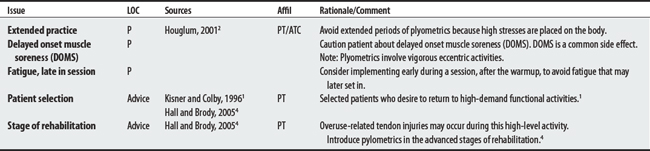

16.7 Plyometrics

OVERVIEW.

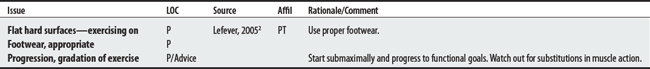

Plyometric training is high velocity, high intensity resistance exercise aimed at increasing muscle power and coordination. The individual performs a resisted eccentric contraction, which is then followed by a rapid concentric contraction.1 The training is typically done toward the latter part of a patient’s rehabilitation program.

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND PRECAUTIONS

M00-M99 DISEASES OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE

R00-R99 SYMPTOMS, SIGNS, AND ABNORMAL CLINICAL & LABORATORY FINDINGS (NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED)

S00-T98 INJURY, POISONING, AND CERTAIN OTHER CONSEQUENCES OF EXTERNAL CAUSES

1 Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1996.

2 Houglum PA. Therapeutic exercises for athletic injuries. Champaign (IL): Human Kinetics, 2001.

3 Brownstein B, Brunner S. Patella fractures associated with accelerated ACL rehabilitation in patients with autogenous patella tendon reconstruction. J Orthopaed Sports Phys Ther. 1997;26(3):168-172.

4 Hall CM, Brody LT. Impairment in muscle performance. In: Hall CM, Brody LT, editors. Therapeutic exercise: moving toward function. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

16.8 Progressive Resistive Exercise

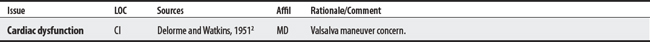

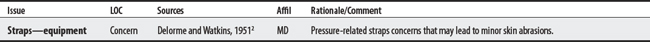

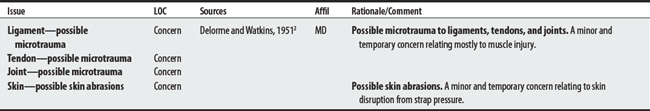

Progressive resistive exercise (PRE) is a form of resistive exercise involving a known, quantifiable load that is increased progressively over time and that is generated by some mechanical means (i.e., equipment). The approach is designed to increase muscle strength, endurance, and power and tends to stress individuals beyond what they are normally accustomed to.1 Delorme’s 1950s approach used exercise apparatus that included the use of straps.2

I00-I99 DISEASES OF THE CIRCULATORY SYSTEM

16.9 Resistance Exercise: General

OVERVIEW.

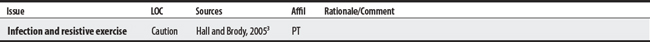

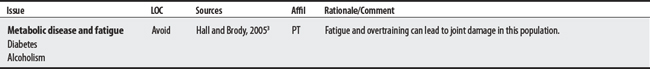

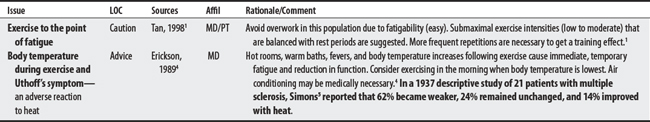

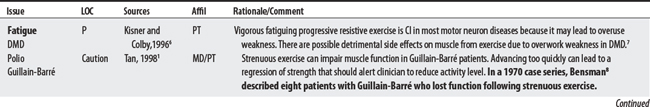

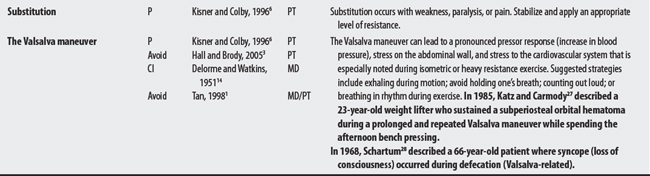

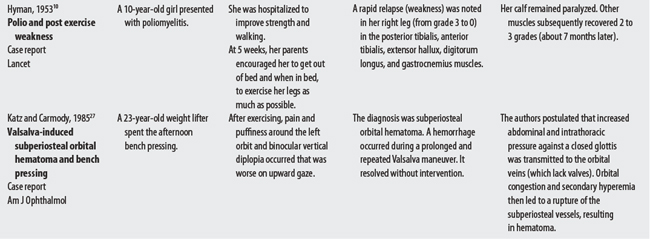

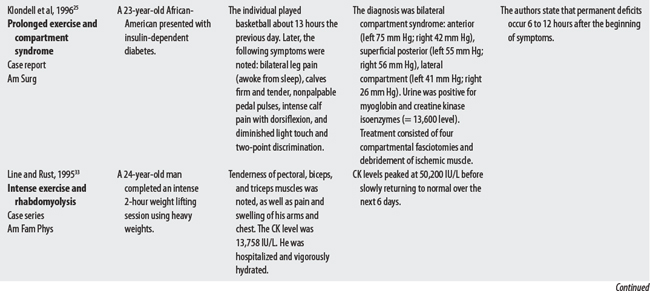

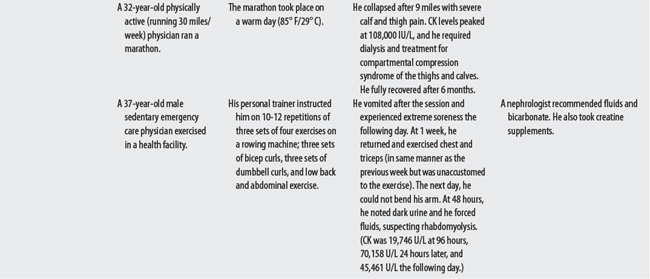

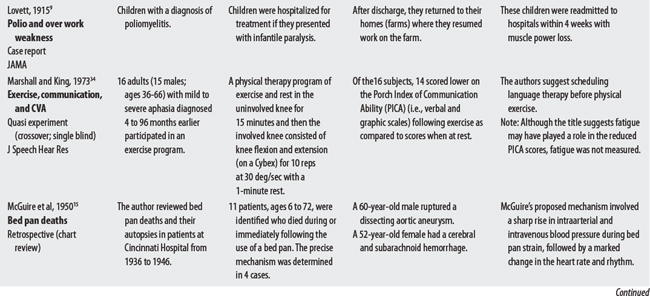

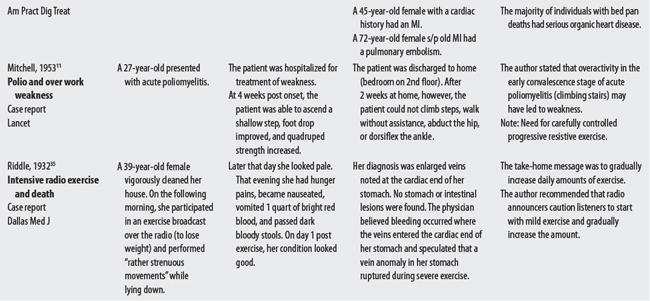

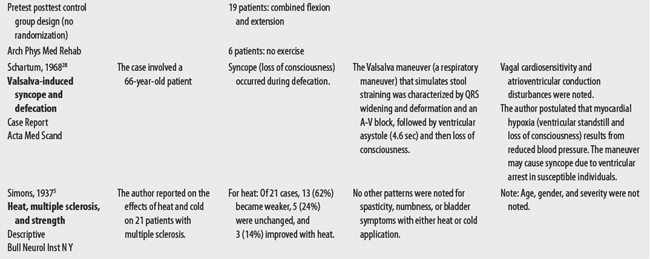

Resistance exercises are active exercises involving static or dynamic muscle contraction that is resisted by an outside force. When specific muscles are targeted for high intensity, high repetition, the activity is referred to as resistance training. The goal of resistive exercise, in general, is to increase strength, power, or endurance.1 Concerns regarding this type of exercise may, in part, be attributed to its exercise-related complications, including rhabdomyolysis, compartmental syndrome, fatigue-related declines in neuromuscular patients, and Valsalva-related morbidity and deaths.

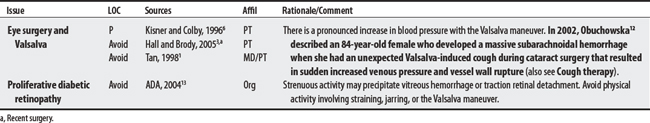

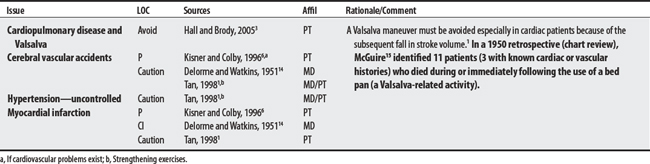

The Valsalva maneuver involves an expiratory effort while the glottis is closed. This maneuver, often unintentional, is one of the chief concerns for resistive exercise, particularly in patients with cardiovascular disease. Valsalva’s (1666-1723) description2 follows: “If the glottis be closed after a deep inspiration and a strenuous and prolonged expiratory effort to be then made such pressure can be extended upon the heart and intrathoracic vessels that the movement and flow of the blood are temporarily arrested.”

Dawson2 cites literature about a bandit who was captured and then committed suicide by performing the Valsalva maneuver in the presence, and to the surprise, of the Roman consul. In doing so, the bandit escaped cross-examination.

A00-B99 CERTAIN INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES

Neuromuscular

I00-I99 DISEASES OF THE CIRCULATORY SYSTEM

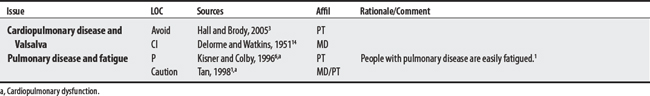

J00-J99 DISEASES OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

K00-K93 DISEASES OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

L00-L99 DISEASES OF THE SKIN AND SUBCUTANEOUS TISSUE

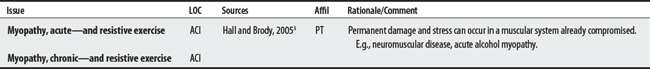

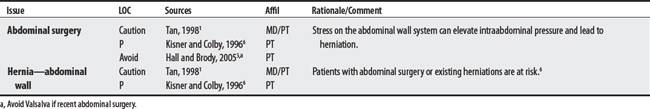

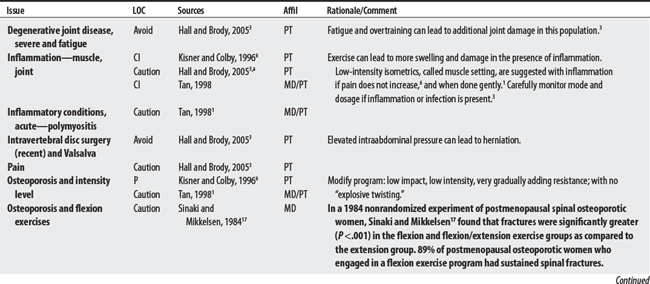

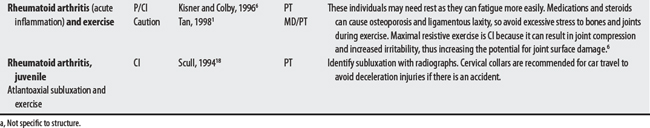

M00-M99 DISEASES OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE

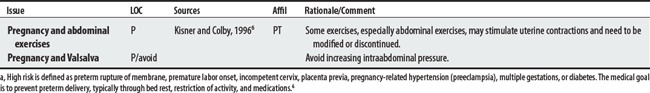

O00-O99 PREGNANCY, CHILDBIRTH, AND PUERPERIUM (ALSO SEE AEROBIC EXERCISES, AROM, AND POSITIONING)

1 Tan JC. Practical manual of physical medicine and rehabilitation: diagnostics, therapeutics, and basic problems. St Louis: Mosby, 1998.

2 Dawson PM. An historical sketch of the Valsalva experiment. Bull Hist Med. 1943;14:295-320.

3 Hall C, Brody LT. Impairment in muscle performance. In: Hall CM, Brody LT, editors. Therapeutic exercise: moving toward function. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

4 Erickson RP, Lie YR, Chiniger MA. Rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:818-828.

5 Simons DJ. A note on the effect of heat and of cold upon certain symptoms of multiple sclerosis. Bull Neurol Inst N Y. 1937;6:385-386.

6 Kisner C, Colby LA. Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1996.

7 Nelson MR. Rehabilitation concerns in myopathies. In Braddom RL, editor: Physical medicine and rehabilitation, ed 2, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2000.

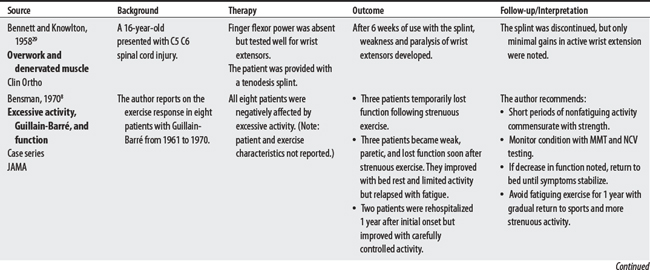

8 Bensman A. Strenuous exercise can impair muscle function in Guillain-Barré patients. JAMA. 1970;214:468-469.

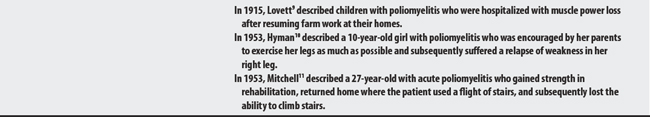

9 Lovett RW. The treatment of infantile paralysis: preliminary report, based on a study of the Vermont epidemic of 1914. JAMA. 1915;64:2118-2123.

10 Hyman G. Poliomyelitis. Lancet. 1953;1:852.

11 Mitchell GP. Poliomyelitis and exercise. Lancet. 1953;2:90-91.

12 Obuchowska I, Mariak Z, Stankiewicz A. [Massive suprachoroidal hemorrhage during cataract surgery: case report]. [Polish]Klin Oczna. 2002;104(5-6):406-410.

13 American Diabetes Association. Physical activity/exercise and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004.

14 Delorme TL, Watkins AL. Progressive resistive exercises: technic and medical application. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1951.

15 McGuire J, Green RS, Hauenstein V, et al. Bed pan deaths. Am Pract Digest Treat. 1950;1:23-28.

16 Spires MC. Rehabilitation of patients with burns. In Braddom RL, editor: Physical medicine and rehabilitation, ed 2, Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2000.

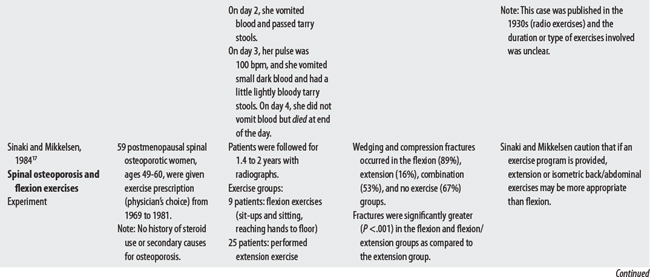

17 Sinaki M, Mikkelsen BA. Postmenopausal spinal osteoporosis: flexion versus extension exercises. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1984;65:593.

18 Scull SA. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. In: Campbell SK, Palisono R, Vander Linden DW, editors. Physical therapy for children. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1994.

19 Helm PA, Kevorkian CG, Lushbaugh M, et al. Burn injury: rehabilitation management in 1982. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1982;63:6-16.

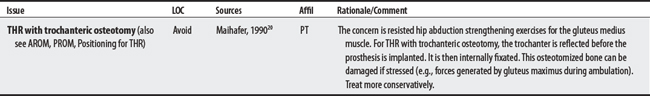

20 Maihafer GC. Rehabilitation of total hip replacements and fracture management considerations. In: Echternach JL, editor. Physical therapy of the hip. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1990.

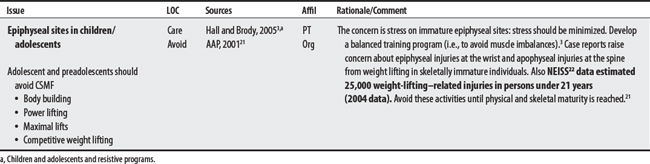

21 American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Strength training by children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1470-1472.

22 U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, National Electronic Injury Surveillance System. Available at: http://www:cpsc.gov/library/neiss.html. Accessed December 16, 2005

23 Sayers SP, Clarkson PM, Rouzier PA, et al. Adverse events associated with eccentric exercise protocols: six case studies. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(12):1697-1702.

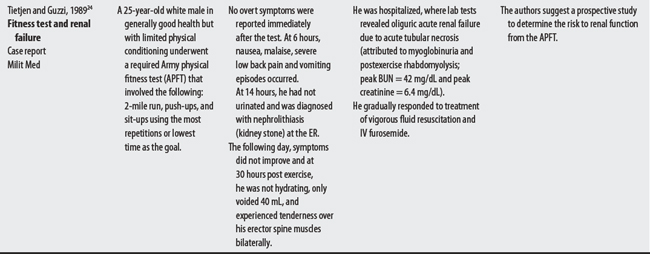

24 Tietjen DP, Guzzi LM. Exertional rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure following the Army Physical Fitness Test. Mil Med. 1989;154(1):23-25.

25 Klodell CTJr, Pokorny R, Carrillo EH, et al. Exercise-induced compartment syndrome: case report. Am Surg. 1996;62(6):469-471.

26 Springer BL, Clarkson PM. Two cases of exertional rhabdomyolysis precipitated by personal trainers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(9):1499-1502.

27 Katz B, Carmody R. Subperiosteal orbital hematoma induced by the Valsalva maneuver. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100(4):617-618.

28 Schartum S. Ventricular arrest caused by the Valsalva maneuver in a patient with Adams-Stokes attacks accompanying defecation. Acta Med Scand. 1968;184(1-2):65-68.

29 Bennett RL, Knowlton GC. Overwork weakness in partially denervated skeletal muscle. Clin Orthop. 1958;12:22-29.

30 Duane TD. Valsalva hemorrhagic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1973;75(4):637-642.

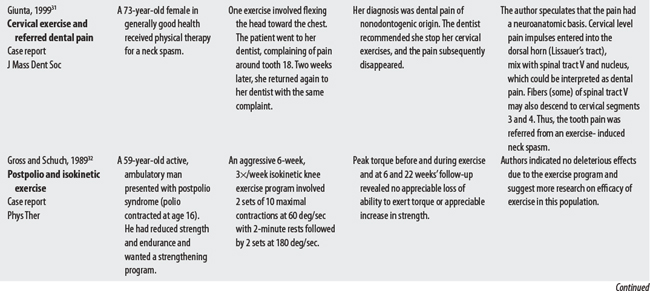

31 Giunta JL. Neck exercises triggering dental pain. J Mass Dent Soc. 1999;48(1):38-39.

32 Gross MT, Schuch CP. Exercise programs for patients with post-polo syndrome: a case report. Phys Ther. 1989;69(1):72.

33 Line RL, Rust GS. Acute exertional rhabdomyolysis. Am Fam Phys. 1995;52(2):502-506.

34 Marshall RC, King PS. Effects of fatigue produced by isokinetic exercise on the communication ability of aphasic adults. J Speech Hear Res. 1973;16(2):222-230.

35 Riddle P. Fatal gastric hemorrhage after radio exercise. Dallas Med J. 1932;18:20.

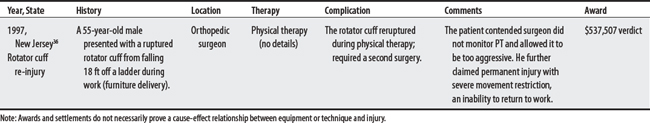

36 Medical malpractice verdict settlement, and experts, September, 1997, p 37, loc 3.

a High risk is defined as preterm rupture of membrane, premature labor onset, incompetent cervix, placenta previa, pregnancy-related hypertension (preeclampsia), multiple gestations, or diabetes. The medical goal is to prevent preterm delivery, typically through bed rest, restriction of activity, and medications.6