CHAPTER 27 Strategies to Enhance Developmental and Behavioral Services in Primary Care

The foundation of pediatric practice is child development. Knowledge and application of the principles of biological development and the interaction between biology and experience are concepts used by pediatricians each day in office and hospital practice. The momentum and focus of a comprehensive pediatric practice is captured in the term biopsychosocial medicine, in which biology, psychology, and social interactions mediate emerging developmental components of childhood, adolescence, and family life.1

Development, in the context of child and adolescent health, refers to the predictable emergence of specific milestones of growth. Pediatricians view these milestones from the perspective of predictable neuromaturational processes during fetal and postnatal brain growth. The interaction between genetic endowment and environmental experience mediates neuromaturation.2

WHY CHANGE AT THIS TIME?

More than half of the parents with children younger than 5 years old report that common developmental and behavioral topics were not discussed during well-child visits. Parents report that they would like more information and support about infant crying (23%), toilet training (41%), discipline (42%), sleep issues (30%), and ways to encourage a child to learn (54%).3 Screening for developmental and behavioral conditions is highly variable, as reported by pediatricians. When asked about office screening practices in an American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Periodic Survey, 96% of pediatricians responded that they screen for these conditions, but only 71% reported using a structured clinical assessment, and only 23% reported using any standardized screening instrument.4 Expanded screening that includes family issues is also variable. Ascertainment of parents’ health by pediatricians is limited in areas of domestic violence, social support, depression, and alcohol or drug abuse.

Developmental and behavioral aspects of primary care practices have been affected by a change in the ecology of many office and clinic practices. For example, only 46% of parents reported that their child had seen the same pediatric clinician for well-child visits up to 3 years of age.5 Continuity of care by one person, a fundamental principle of primary care, has been replaced by continuity within one clinic or office.6 Many children do not even have the benefit of the number of well-child visits recommended by the AAP; nationally, only half of the well-child visits recommended by the AAP are completed in the first 2 years of life.7

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Pediatrics has a long history of attention to preventive aspects of child health care. Nineteenth century pioneers of pediatrics in Europe and America focused on descriptions of childhood diseases, but they soon recognized the value and importance of prevention. Abraham Jacobi, one the founders of pediatrics as a specialty for children, devoted his work to the elimination of the deadly summer diarrhea epidemics in New York City by emphasizing prevention through hygiene in the preparation of milk and other foods for young children.8 At the opening of the 20th century, periodic and frequent weight determinations in infants and young children in public health clinics was a way to monitor children’s general health and well-being. As a part of America’s Progressive Movement from 1900 to 1920, the U.S. Children’s Bureau proposed that monitoring the weight of young children should be the central activity for the National Year of the Child in 1918 in order to diagnose malnutrition.9

Nurses, social workers, and lay reformers planned and implemented these screening programs as a part of the child welfare movement in cities and small communities throughout the country. Eventually, physicians who cared for children adopted routine weight and height measurements in their offices and clinics as a part of overall supervision of a child’s health. A major force that led to the establishment of the AAP in 1930 was a recognition that pediatric care would improve significantly when pediatricians adopted a prevention-oriented strategy and collaborated with the leaders of the child welfare movement. In 1933, the president of the AAP made the radical (for that time) proposition that pediatricians should begin to offer periodic health examinations. This may have marked the beginning of primary care pediatrics and standard well-child visits. In 1910, there were approximately 100 physicians who limited their practice to children. By 1930, there were several thousand; it is estimated that a third of their visits were for well-child care.9 In 2000, the AAP had almost 60,000 members.

Developmental and behavioral health care for children in the context of pediatric practice was an outgrowth of these early events. Leaders in pediatrics wrote about the importance of attention to the social and psychological development of children during pediatric encounters. Significant contributions to the practice of well child care were made by many pioneers, including Anderson Aldrich, Edith Jackson, Morris Wessel, Milton Senn, Helen Goffman, and Benjamin Spock.10 They increased the attention of pediatricians to motor, language, and social skill development of young children; the importance of assessing mother-child attachment and educational achievement; and the development of a therapeutic alliance in optimizing all aspects of pediatric care.

These historical trends are antecedents to the schedule of well-child visits used in contemporary pediatrics. The so-called periodicity schedule was established in the 1960s by a group of pediatricians working with the AAP. It was based on the best clinical judgment available at the time and guided by the immunization schedule. Since the 1950s, multiple additional topics for assessment and anticipatory guidance have been added to the initial template.11 Unfortunately, developmental themes and psychosocial tasks among children and families that are unique to each age group have not led to specific recommendations and guidance about optimal structuring of well-child visits or to their increased frequency or duration.

WELL-CHILD VISITS: WHAT DO WE DO THAT IS EVIDENCE-BASED?

Medical care, including preventive medicine, strives for a foundation of evidence-based studies to support clinical practice. There are some areas of well-child care that are supported by strong evidence from randomized controlled studies. Examples of these practices include standard immunizations,12 promoting good nutrition during infancy,13 encouraging parents to put their infants to sleep on their backs,14 and the judicious use of antibiotics for respiratory infections.15

Other components of well-child care practices that focus on the development and behavior of children have not been studied with large randomized trials. A careful review of published studies reveals support for some practices, suggestions for new directions, and opportunities for further research. Regalado and Halfon16 reviewed published studies on evaluations of four areas of developmental and behavioral pediatric practice in children from birth to 3 years of age. These studies reflect the potential for current clinical practices. Regalado and Halfon’s conclusions were the following:

CLINICAL INTERVIEW AND THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP

As in most areas of medical practice, clinicians rely on the medical interview to determine patients’ (and parents’) concerns. A detailed and focused medical history, including psychosocial and biological factors in an individual and family, suggests a diagnosis. The mutual trust that is the outcome of a therapeutic alliance between patient (parent and child) and clinician is the core of clinical practice.

Clinical strategies that enhance the therapeutic relationship include the following:

Entering the examination room, the pediatrician observes that the mother of a toddler appears sad and pale; eye contact with the pediatrician is minimal and difficult to encourage. The child plays in a corner of the room without mother-child interchange. There is not enough information to suggest a diagnosis, but the initial impression is maternal depression. An empathic introductory comment, “You appear sad today” often opens a dialogue. If the mother does not respond, suggest, “Is there something you’d like to talk about—about your child or something in the family?”

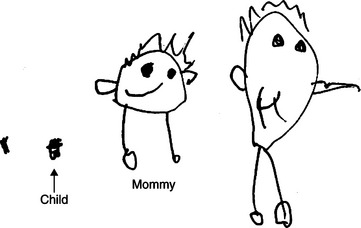

Entering the examination room, the pediatrician observes that the mother of a toddler appears sad and pale; eye contact with the pediatrician is minimal and difficult to encourage. The child plays in a corner of the room without mother-child interchange. There is not enough information to suggest a diagnosis, but the initial impression is maternal depression. An empathic introductory comment, “You appear sad today” often opens a dialogue. If the mother does not respond, suggest, “Is there something you’d like to talk about—about your child or something in the family?” A mother, father, and 5-year old come to the office for a 2-week well-child visit for the new addition to the family. Mother’s facial appearance and minimal body movements suggest sleep deprivation. The father, in contrast, is ebullient about his new son. The 5-year old draws a picture of his family that reveals these nonverbal communications (Fig. 27-1).

A mother, father, and 5-year old come to the office for a 2-week well-child visit for the new addition to the family. Mother’s facial appearance and minimal body movements suggest sleep deprivation. The father, in contrast, is ebullient about his new son. The 5-year old draws a picture of his family that reveals these nonverbal communications (Fig. 27-1). An 8-year-old girl sits in the chair biting her nails with slightly flexed truck and neck. She fidgets and responds to questions in short phrases. Inquiries about school and friends are followed by splotchy areas of erythema on her neck and face. Nonverbal body language suggests an anxiety state and an opportunity to gently probe her concerns. If she remains silent, spending time with her parent alone while the child is asked to draw a picture of her family may be a good strategy to encourage communication.

An 8-year-old girl sits in the chair biting her nails with slightly flexed truck and neck. She fidgets and responds to questions in short phrases. Inquiries about school and friends are followed by splotchy areas of erythema on her neck and face. Nonverbal body language suggests an anxiety state and an opportunity to gently probe her concerns. If she remains silent, spending time with her parent alone while the child is asked to draw a picture of her family may be a good strategy to encourage communication. A 4-year-old monitored since birth with a slow-to-warm-up temperament refuses to speak to the pediatrician. Her mother notes that she thinks his behavior is appropriate for a younger child; language acquisition continues to be delayed. A neuromaturational developmental screening test suggests global delay. Mild or moderate cognitive delay may be missed when an attractive, nondysmorphic child with minimal social responsiveness is assumed to be shy and temperamentally slow to warm up.

A 4-year-old monitored since birth with a slow-to-warm-up temperament refuses to speak to the pediatrician. Her mother notes that she thinks his behavior is appropriate for a younger child; language acquisition continues to be delayed. A neuromaturational developmental screening test suggests global delay. Mild or moderate cognitive delay may be missed when an attractive, nondysmorphic child with minimal social responsiveness is assumed to be shy and temperamentally slow to warm up.

FIGURE 27-1 Enhancing the communication process between pediatrician and parents during a well child visit (see text).

There are many opportunities to fine-tune a clinical interview with children and parents (Table 27-1). These methods have been studied and used by experienced clinicians who recognize the value of the clinical interview as a means of acquiring information and counseling children and families.19 In addition, the physical proximity between the pediatrician, child, and family members may orchestrate the interview. Physical barriers to communication should be avoided (Table 27-2).

TABLE 27-2 Positioning the Participants during a Pediatric Interview to Enhance Observations and Communications

From Stein MT: Developmentally based office: Setting the stage for enhanced practice. In Dixon SD, Stein MT, eds: Encounters with Children: Pediatric Behavior and Development, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2006, p 78.

SCREENING FOR DEVELOPMENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL CONDITIONS WITH CHECKLISTS AND QUESTIONNAIRES

In contrast to informal screening, the advantage of a systematic screening questionnaire used in the course of a well-child visit is that predictable areas are assessed at each visit by asking a parent about specific neurodevelopmental achievements and behaviors. Many standardized questionnaires and observational tools have been developed for use in primary care pediatric practices17a (see Chapter 7B).

One innovation to incorporate developmental and behavioral issues into primary care is the Child Health and Development Interactive System (CHADIS). Parents complete questionnaires and computerized interviews online through an electronic decision support system, before a well-child care visit. The questionnaires are scored by the computer, which generates a list of prioritized parent concerns and scored questionnaires. These results provide evidence of behavioral and developmental concerns consistent with formats in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV),19a and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care (DSM-PC): Child and Adolescent Version.19b The results are also linked to resources, including parent handouts, national level organizations, books, and videos, and local resources such as mental health clinicians, support groups, mentors, agencies, and activities.20

Screening questionnaires should be viewed as a supplemental aid to the clinical interview. When they are available before the interview, screening instruments may guide the clinician’s area of inquiry, focus the visit on a particular topic that emerges from the questionnaire, or provide an opportunity for the parent or child to clarify a response on the questionnaire. They should not be used as a substitute for clinical observations, and interviewing must be tailored to the needs of each child and family. Patients and children need to “tell their own story”21—a process that is enhanced by the trust that develops through a therapeutic relationship based on sensitive interpersonal communication with children and parents (Table 27-3).

TABLE 27-3 Screening Checklists as Aids to Interview: Benefits and Risks

Modified from Dixon SD, Stein MT: Encounters with Children: Pediatric Behavior and Development, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2006, p 727.

INNOVATIONS TO ENHANCE QUALITY AND BREADTH OF ATTENTION TO DEVELOPMENT AND BEHAVIOR IN OFFICE PRACTICE

Group Office Visits

PARENT GROUP DISCUSSIONS

In some primary care pediatric practices, the group discussion model has been adapted to address preventive topics. The focus can be on a developmental stage (e.g., in toddlers, school-aged children, adolescents), a particular topic (e.g., nutrition, tantrums and discipline, home safety, school underachievement, substance abuse), or a condition (e.g., asthma/allergies, recurrent ear infections, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, eating disorders, divorce). Some pediatricians have found the well-child visit before kindergarten entry especially suitable for this format. Some practices are beginning to experiment with the notion of providing actual behavioral guidance to selected parents in groups.21a

GROUP WELL-CHILD CARE

An innovative use of the group process in pediatric practice has been the group well-child model.22 In this model, children and their parents are seen for health supervision visits in the first few years of life, not individually but in small groups of parents and infants. Beginning usually with the first well-child visit after the child’s birth, a group of infants and parents meet (usually 45 minutes) to discuss issues of general interest. The clinician is in the roles of both an educator and facilitator. Parent concerns guide the discussion. Because their children are of similar age, parents typically have similar concerns, and they learn from each other as well as from the clinician-facilitator. After the group discussion, each child is examined; the physical and developmental assessment can occur within the group or individually. Group well-child care was developed in an effort to find a method of delivering well-child care that includes more attention to development and behavior; is also cost effective, efficient, and satisfying to parents; and includes all the substantive content found in traditional individual care. It has the added advantage of creating a mutually supportive group of parents who can share their parenting experiences while observing a range of developmental and behavioral characteristics.

Studies comparing group and traditional well-child care visits document several assets but also suggest limitations of the group process. A study of typically developing children in group well-child care found improved attendance at well-child visits, fewer calls between visits, more time for personal issues, and more open-ended questions.23 In another study, more well-child care topics were discussed, including safety, nutrition, behavior, development, sleep, and parenting.24 Parents’ child care knowledge, social support, and maternal depressive symptoms were compared between groups and traditional models and found to be surprisingly similar.25 Group well-child visits have been studied among high-risk families, for which higher no-show rates were found with group well-child care but no differences were seen in child development status, maternal-child interactions, home environment, provider time spent at visits, parental competence, social isolation, social support, and reports to child protective service.26,27

Teachable Moments

“Teachable moments” are opportunities for a clinician to comment about or demonstrate a response to a child’s behavior or to communicate information during the physical, developmental, and behavioral examinations. They are unplanned opportunities to provide information, promote discussion, and support parents. Observation of a difficult temperament, a child’s refusal to cooperate during a physical examination, and concern about maternal depression are examples of teachable moments. They occur frequently during both well-child and illness-related visits. In a busy practice, not every observed event that the clinician would like to comment on can be used as a teachable moment. Conscious vigilance for these opportunities and a commitment to responding to them several times each day enhance quality of care, satisfaction with the practice, and intellectual stimulation of the pediatrician (Table 27-4).

| Jake has been a healthy child before his health supervision visit at 18 months old. As you enter the examination room, you observe Jake playing on the floor with a plastic toy that has several movable parts. He appears engaged and intent on mastering the toy. You also notice that his fine motor skills are mature for his age when you observe Jake drawing. Jake appears not to notice you when you enter. Shortly after you begin to gather information from his mother, Jake’s activity level and focus change dramatically. He starts hitting the toy, screams “bad … bad,” and throws the toy into a wall. He starts to cry, resists his mother’s attempt to hold him while she provides reassuring words, and hits her with his hand several times. His mother begins to cry and says, “He was such a good baby. In the last few months, he’s a different child—selfish, angry, and always throwing a tantrum.” You are faced with several options at this point:

1. Quickly perform a physical examination, check the growth chart, and order immunizations (and a blood lead and hematocrit if appropriate).

2. Talk to Jake’s mother about tantrums and the need for discipline. Provide a handout on toddler development and discipline.

3. Attempt to engage Jake with words and a toy (i.e., sit down on the floor and play with the toy and say something like: “Gee, this is a great toy. I can make the door open so the boy can go inside.”). Alternatively, address Jake and say, “It’s real hard to come to the doctor!” or, “You are real upset at the doctor’s office.” Follow these words with silence and wait patiently for Jake’s response.

The first option brings closure to the office visit but does not address Jake’s behavior. The second option demonstrates recognition of a problem and expands the mother’s knowledge about toddler behaviors and approaches to discipline. The third option illustrates immediate recognition of a “teachable moment.” The pediatric clinician chooses to model an age-appropriate response to a tantrum through action and language. Engaging the child formulates the scene to the child’s reality. The pediatrician’s language is direct and brief; she tries to mirror the child’s feelings with a few words and waits for a response. This technique, known as “active listening,” encourages Jake’s mother to learn that she can interact with her son at these difficult moments by feeding back to him the feelings he is experiencing. The clinician’s modeling of the behavior can be followed by the information exchange illustrated in the second option. |

From Stein MT: Developmentally based office: Setting the stage for enhanced practice. In Dixon SD, Stein MT, eds: Encounters with Children: Pediatric Behavior and Development, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2005, p 80.

“Reach Out and Read”

This creative, office-based intervention was developed by a group of pediatricians to promote literacy, language skills, and a close parent-child attachment through reading to children at an early age. The rationale for the Reach Out and Read (ROR) program is that poor reading skill among many children in elementary school is associated with limited exposure to reading aloud during preschool years. A meta-analysis of 29 studies revealed a significant association between early reading aloud and later academic outcomes.29

A number of studies have evaluated some form of the ROR program in pediatric settings; three of the studies are prospective controlled trials. Results of 12 studies support an association between ROR and increased reading aloud at home; four studies revealed that children in the program show increases in expressive and receptive language at 2 years of age in comparison with children in control groups.30 In a large study including 730 parents who participated in ROR in 19 clinical sites in 10 states, and 917 parents from the same clinics who did not participate in the program, significant associations were found between exposure to ROR and reading aloud as a favorite parenting activity, reading aloud at bedtime, reading aloud 3 or more days per week, and ownership of 10 or more picture books.31

Co-location of Mental Health Clinicians

One solution that has been proposed to address this dilemma is to co-locate a mental health consultant in the pediatric office.31a A referral can be made more efficiently to “my colleague in the office” rather than to someone in another office building. Communication between the primary care clinician and the consultant, and common recordkeeping, are facilitated. For some families, the location of the mental health clinician in the pediatrician’s office reduces the stigma associated with a mental health referral. Billing for mental health services may be done synchronously or independently, depending largely on the structure of health insurance plans in the community. In large staff-model health maintenance organizations and in some multispecialty community clinics, mental health services may be seamlessly included; however, the office of the mental health professional is still often physically distant from the primary care clinician, and some of the potential benefits of the collegial relationship are sacrificed.

Healthy Steps

An innovative form of co-locating care is the Healthy Steps model. The goal of this system of care is to increase a clinician’s ability to address behavioral, emotional, and cognitive development in early childhood. To achieve this goal and create a strong bond between clinicians and parents, a specialist in child development—trained in pediatric nursing, early childhood education, or social work—is added to the practice staff to provide enhanced well-child care.32 In this model, the child development specialist is an additional staff member whose role supplements those of the pediatrician and the office nurse. Her or his activities may include the following:

Focusing on promotion of children’s development, including strategies to improve “the goodness of fit” between parent and child; paying closer attention to parental questions and concerns.

Focusing on promotion of children’s development, including strategies to improve “the goodness of fit” between parent and child; paying closer attention to parental questions and concerns. Meeting with parents before, during, and after well-child visit to discuss behavioral and developmental concerns.

Meeting with parents before, during, and after well-child visit to discuss behavioral and developmental concerns.An evaluation of Healthy Steps included 5565 children and their parents at 15 sites.28 Research demonstrated that parents in the program acquired more knowledge about child development and behavior and were better able to use community resources than control parents, who used traditional pediatric care. Families involved in the Healthy Steps program received significantly more preventive and developmental services than did families in the control group. They were more likely than nonparticipating families to

Discuss with someone in the practice the importance to children of routines, discipline, language development, temperament, and sleeping patterns.

Discuss with someone in the practice the importance to children of routines, discipline, language development, temperament, and sleeping patterns. Have greater adherence to visits, nutritional guidelines, developmental stimulation, and use of appropriate discipline techniques.

Have greater adherence to visits, nutritional guidelines, developmental stimulation, and use of appropriate discipline techniques. Be more sensitive to their child’s signals during play and more likely to match their interactions to their child’s developmental level, interests, and capabilities.

Be more sensitive to their child’s signals during play and more likely to match their interactions to their child’s developmental level, interests, and capabilities.The positive effects of the program were identified for all parents regardless of their income, parity, or maternal age. On the other hand, other measured outcomes showed no significant differences between the groups; these outcomes included initiation or duration of breastfeeding, child development knowledge, sense of competence, self-report of nurturing behavior and expectation of children, reports of children’s language development at 2 years of age, and safety practices.28

Collaborative Office Rounds

Programs known as collaborative office rounds have been initiated in many communities to develop and support effective relationships between pediatricians and mental health professionals.33 These group meetings consist of 8 to 12 pediatricians and one or two mental health clinicians who meet once or twice a month to discuss clinical cases that are challenging and engaging to the participants. Some of these groups also include a specific topic for discussion at some of the sessions. Supplementary readings, audio recording of office interviews with children and parents, invited experts from the community, and families invited to contribute to the discussion have been additional components. These ongoing group meetings have been evaluated and appear to provide

Building Consensus with Staff

During meetings with the nurses and nonprofessional office staff and through selective printed material and videotapes, the clinic staff can receive education about major themes of development at each age group, developmental milestones, and common problems in development and behavior at specific ages. The goal of this educational process should be to empower the office staff to be sensitive “observers” of social interactions throughout the office visit and to prevent missed opportunities for important observations: when making an appointment by phone, at the time a parent and child check in with the office receptionist, when weighing and measuring a child, and when asking about a parent’s concerns for the visit. These moments are opportunities to observe parent-child interactions in a context that may not be available to the pediatrician in the examination room. The office staff should be encouraged to communicate their observations to the child’s clinician (Table 27-5). Periodic discussions during staff meetings with case examples from the office serve to reinforce the importance of staff observations.

TABLE 27-5 Notes from Medical Assistants Who Make an Important Observation while Preparing a Child or Youth for an Office Visit

|

2-Month-old’s well-child visit: “Mom seems tired or depressed … few words and awkward when handling the baby.”

|

COMMUNITY-BASED NEEDS ASSESSMENT

Pediatric practices might consider borrowing a public health method to assess the needs of a community with regard to behavioral and developmental concerns of parents who bring their children to the practice. Socioeconomic, educational, and ethnic differences create different concerns. Environmental hazards, child care opportunities, and school curriculum and health services are among a few examples of community differences. An example of community-based needs assessment is evidenced in primary care family practice in Cuba, where a doctor and nurse are responsible for about 180 families surrounding the office neighborhood. An initial and ongoing assessment of health and psychosocial needs is the responsibility of the physician and nurse. Preventive programs and health education are formulated from the results of the assessments.35

COORDINATION OF CARE AND LINKAGES WITH COMMUNITY RESOURCES

A primary care pediatric office should serve as the coordinator of care for the medical, educational, and psychosocial needs of children. These activities are a major component of the medical home (see Chapter 8B). An individual provider of care (or a single office) cannot fulfill all the needs of all children and families. Coordinated care with community resources is crucial for effective developmental and behavioral services for children and adolescents. Coordinated services for children with disabilities have been organized in some communities through a network whereby initial referrals and monitoring of referrals are organized by a central agency that works closely with each pediatric practice in the community to ensure access to appropriate services. An extensive outreach program links at-risk children and their families to programs and services.36

Specialty medical consultations (e.g., neurology, genetics, audiology, speech therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy, orthopedics).

Specialty medical consultations (e.g., neurology, genetics, audiology, speech therapy, occupational therapy, physical therapy, orthopedics). Families with children with chronic physical or developmental disabilities who agree to meet with other families to share their experiences.

Families with children with chronic physical or developmental disabilities who agree to meet with other families to share their experiences.Some primary care practices have created a Parent Advisory Group made up of parents of children with a variety of chronic physical and developmental disabilities. The group provides ongoing suggestions about improvements in the care of children with chronic conditions. The parent group may also link with advocacy groups in the community bringing information and resources into the practice.36a

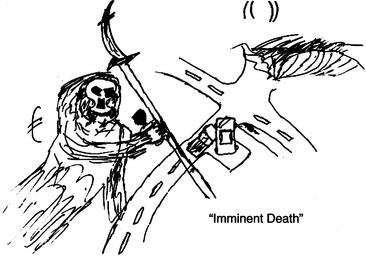

FAMILY DRAWINGS: AN OPPORTUNITY FOR ENHANCED COMMUNICATION WITH PARENTS AND CHILDREN

Children naturally like to draw. The regular use of drawings can make a number of contributions to a child’s visit to the pediatric office or clinic. The information obtainable from routinely asking a child to “draw a picture of your family” at all health supervision visits beginning at 4 or 5 years of age may be considerable. Drawing a picture may lessen the stress of a visit to the pediatric office; help the clinician assess fine motor and visual-perceptual abilities; and provide information about the child’s sense of self, developmental status, family relationships, and adaptation to stress.37

Although a single figure in the drawing may be used as a screening test of visual-perceptual/fine motor maturation, there is often more to gain by using the family drawing as an opportunity to discuss issues about the child or family that do not surface during many pediatric office encounters. Asking a child to talk about the picture (“Tell me about the people you drew in your picture”) or targeting a particular aspect of the drawing (“Where is your daddy… or your sister?”) often provides an opportunity to engage a child or parent in a topic that may have been too difficult to talk about without the benefit of the drawing. At best, the dialogue generated by the drawing becomes a therapeutic discussion among the parents, child, and clinician. A sense of control and ownership in the visit to the pediatrician builds a foundation for involvement in and responsibility for health and health care. In addition, the drawings can also make parents aware of a stressful experience that has not been previously disclosed by the child. Sequential drawings should be part of the medical record to mark the child’s development, to monitor both ordinary and extraordinary adaptive stress, and to serve as a developmental screen (Figs. 27-2 to 27-4).38

DEVELOPMENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL PEDIATRIC TRAINING FOR PEDIATRIC RESIDENTS

The specialty of developmental/behavioral pediatrics was supported by the recognition that pediatric training programs require a faculty member with knowledge, clinical skills and research programs in normal and abnormal development.39 Teaching medical students, residents and practicing pediatricians remains a significant component of the specialty.

Normal pathways of motor, social, language, and cognitive development are too often given short shrift in residency training programs. A list of developmental milestones often suffices. At least one textbook with a focus on resident education in normal development and behavior is available.40 Reading, however, only begins the process of understanding developmental and behavioral differences among typically developing children. Supervised observations (in an office, child care center, school, or playground) are crucial for learning about children.

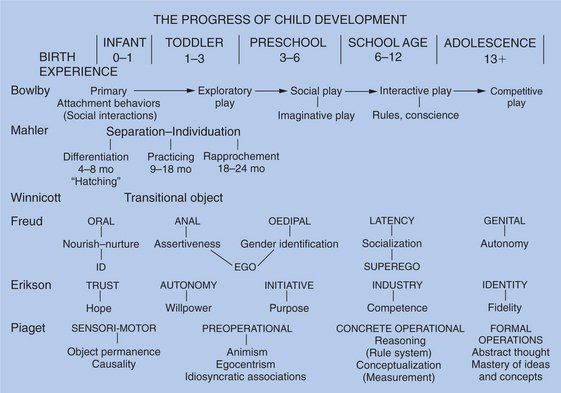

Pediatric residents and community-based pediatricians can be engaged in developmental theories as a method of discovering different perspectives on developing children, adolescents, and families and understanding unifying constructs of development adaptable to clinical practice. Theories of child development can assist pediatric clinicians in their understanding of variations in behavior and development from different perspectives (see Fig. 27-5). Neuromaturational, cognitive, behavioral, psychoanalytic, and psychosocial theories each bring a unique language to the understanding of child development. The language in each theory can assist clinicians in helping parents gain insights into their children that may lead to alternative childrearing strategies.

FIGURE 27-5 The progress of child development as described by several major theorists

(John Bowlby, Margaret Mahler, D. W. Winnicott, Anna Freud, Erik Erikson, and Jean Piaget).

RETHINKING WELL-CHILD CARE

Pediatricians are beginning the process of rethinking the format and content of well-child care, especially with regard to the prevention, identification, and treatment of developmental and behavioral conditions.44 Many ideas are emerging. Some examples include the following:

SUMMARY: ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS OF “THINKING DEVELOPMENTALLY” DURING PRIMARY CARE OFFICE PEDIATRIC ENCOUNTERS

“Biopsychosocial Pediatrics” Is a Useful Mantra

Pediatric medicine is practiced optimally with frequent considerations of biological, social, and psychological elements of care. Children with streptococcal tonsillitis, chronic recurrent asthma, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or anxiety all benefit from the biopsychosocial model of medical practice in that it links important aspects of a child’s life with each other. Thinking biopsychosocially expands a clinician’s care to include the whole patient and does not limit clinical thinking and patient interactions to an isolated disease process.47

Brain Maturation and Plasticity

The structure of the human brain continues to change during childhood and adolescence through a process of synapse generation and pruning. Recognition that these changes are mediated by the quality of environmental experience has fueled pediatricians’ goal to help families optimize the development of their children. Emotionally healthy conditions in the home, school, and neighborhood interact with genetic endowment to provide appropriate brain maturation and sustain adequate development.2 Nature and nurture are always interacting as developmental and behavioral change occurs. The developmentally oriented pediatrician who is aware of this interaction usually conveys a more optimistic and realistic perspective at each clinical encounter.

1 Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129-136.

2 Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA, editors. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: the Science of Early Childhood Development Washington. DC: National Academies Press, 2000.

3 Young KT, Davis K, Schoen C, Parker S. Listening to parents: A national survey of parents with young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:255-262.

4 Sand N, Silverstein M, Glascoe FP, et al. Pediatricians’ reported practices regarding developmental screening: Doguidelines work? Pediatrics. 2005;116:174-179.

5 Inkelas M, Schuster MA, Olson LM, et al. Continuity of primary care clinician in early childhood. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6 Suppl):1917-1925.

6 Alpert JJ, Zuckerman PM, Zuckerman B. Mommy, who is my doctor? Pediatrics. 2004;113(6 Suppl):1985-1987.

7 Kogan MD, Schuster MA, Yu SM, et al. Routine assessment of family and community health risks: Parent views and what they receive. Pediatrics. 2004;113(6 Suppl):1934-1943.

8 Cone TEJr. History of American Pediatrics. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1979.

9 Brosco JP. Weight charts and well-child care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1385-1389.

10 Baker JP, Pearson HA, editors. Dedicated to the Health of All Children. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

11 American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine. Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000.

12 Pickering LA, editor. Redbook, 27th ed., Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006.

13 Kleinman RE, editor. Pediatric Nutrition Handbook, 5th ed., Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2004.

14 Task Force on Sudden Infant Death. The changing concept of sudden infant death. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1245-1255.

15 Siegel RM, Kiely M, Bien JP. Treatment of otitis media with observation and a safety-net antibiotic prescription. Pediatrics. 2003;112:527-531.

16 Regalado M, Halfon N. Primary care services promoting optimal child development from birth to age 3 years. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1311-1322.

17 Glascoe FP. Collaborating with Parents: Using PEDS to Detect and Address Developmental and Behavioral Problems. Nashville, TN: Ellsworth VandeMeer Press, 1998.

17a. Perrin EC, Stancin T. A continuing dilemma: Whether and how to screen for concerns about children’s behavior. Pediatr Rev. 2002;23:264-275.

18 American Academy of Pediatrics. Guidelines for Health Supervision III, 3rd ed., Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2002:3.

19 Lipkin MLJr, Putnam SM, Lazare A. The Medical Interview-Clinical Care, Education, and Research. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1995.

19a. American Psychiatric Association. Primary Care Version. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995.

19b. American Academy of Pediatrics. The classification of child and adolescent Mental Diagnosis in Primary Care-Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care (DSM-PC) Child and Adolescent Version. Elk Grove Villiage, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 1996.

20 Sturner R, Howard B: CHADIS. (Available at: www.childhealthcare.org; accessed 2/22/07.)

21 Cole R. The Call of Stories: Teaching and the Moral Imagination. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1990.

21a. Sheldrick R, McMenamy J, Kavanaugh K, Tannebring E, Perrin E: A Preventive Intervention for ADHD in Pediatric Settings [poster]. Pediatric Academic Societies, May 2005.

22 Stein M. The providing of well baby care within parent-infant groups. Clin Pediatr. 1977;16:825.

23 Osborn LM, Woolley FR. Use of groups in well child care. Pediatrics. 1981;67:701-706.

24 Dodds M, Nicholson L, Muse B, et al. Group health visits more effective than individual visits in delivering health care information. Pediatrics. 1993;9:668-670.

25 Rice RL, Miles CE, Slater CJ. An analysis of group versus individual health supervision visits. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:488.

26 Taylor JA, Davis RL, Kemper KJ. A randomized controlled trial of group versus individual well child care for high-risk children: Maternal-child interaction and developmental outcomes. Pediatrics. 1997;99:e9.

27 Taylor JA, Kemper KJ. Group well-child care for high-risk families. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:579-584.

28 Zuckerman B, Parker S, Kaplan-Sanoff M. Healthy Steps: A case study of innovation in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2004;114:820-826.

29 Bus AG, van Ijzendoorn M, Pelligrini A. Joint book reading makes for success in learning to read: A meta-analysis on intergenerational transmission of literacy. Rev Educ Res. 1995;65:1-21.

30 Needlman R, Silverman M. Pediatric interventions to support reading aloud: How good is the evidence? J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:352-363.

31 Needlman R, Toker KH, Dreyer BP, et al. Effectiveness of a primary care intervention to support reading aloud: A multi-center evaluation. Ambul Pediatr. 2005;5:209-215.

31a. Perrin EC. The promise of collaborative care. Dev Behav Pediatr. 1999;20:57-62.

32 Minkovitz CS, Hughart N, Strobino D, et al. A practice-based intervention to enhance quality of care in the first three years of life: Results from the Healthy Steps for Young Children Program. JAMA. 2003;290:3081-3091.

33 DeMaso DR, Knight JR: The Collaboration Essentials Office Rounds Case Manual. (Available at: http://collaborationEssentials.org/ce/using/index.html.)

34 Fishman ME, Kessel W, Heppel DE, et al. Collaborative office rounds: Continuing education in the psychosocial/developmental aspects of child health. Pediatrics. 1997;99:e5.

35 Swanson KA, Swanson JM, Gill AE, et al. Primary care in Cuba: A public health approach. Health Care Women Int. 1995;16:299-308.

36 Dworkin PH. Historical overview: From ChildServ to Help Me Grow. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(1 Suppl):S5-S7. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(1 Suppl):S17-S21. [discussion, S50–S52]

36a. Young M, McMenamy JM, Perrin EC. Parent advisory groups in pediatric practices: Parents’ and professionals’ perceptions. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:692-698.

37 Stein MT. The use of family drawings by children in pediatric practice. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1997;18:334.

38 Welsh JB, Instone SL, Stein MT. Use of drawings by children at health encounters. In: Dixon SD, Stein MT, editors. Encounters with Children: Pediatric Behavior and Development. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006:98-121.

39 Haggerty RJ, Friedman SB: History of developmental-behavioral pediatrics. J Dev Behav Pediatr 24 (Suppl):S1-S18.

40 Dixon SD, Stein MT. Encounters with Children: Pediatric Behavior and Development, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2006.

41 Stein MT. Challenging cases in developmental and behavioral pediatrics. J Dev Behav Pediatr Suppl. 2001;22(Suppl 25):S1-S184. 1–1112004

42 Pedicases: A series of primary care problems including development and behavior. (Available at: www.pedicases.org.)

43 Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: Training Modules on Clinical Issues in Primary Care [DVD]. New York: Commonwealth Fund, 2006. (Available at: http://www.cmwf.org/tools/tools_show.htm?doc_id=360961; accessed 2/22/07.)

44 Schor EL. Rethinking well-child care. Pediatrics. 2004;114:210-216.

45 American Academy of Pediatrics. Parent/child guides to pediatric visits. In: Guidelines for Health Supervision III. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2002:247-256.

46 American Academy of Pediatrics. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: An algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:405-420.

47 Apley J, Ounsted C, editors. One Child. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1982.

48 Perrin EC. Ethical questions about screening. Commentary. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19:350-352.