Ureteral Stone

Synonyms/Description

Renal stone

Kidney stone

Nephrolithiasis

Etiology

Renal and ureteral stones are typically calcium stones (calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, or mixed calcium oxalate and phosphate). A minority (20%) of stones are uric acid, cystine, and struvite in origin. They become especially symptomatic when they travel down the ureter and become lodged, causing a blockage in the flow of urine.

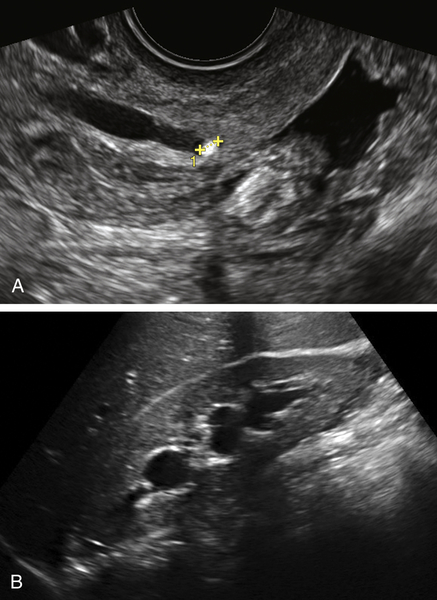

Ultrasound Findings

Sonography is very useful in visualizing stones at the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ), the ureterovesical junction (UVJ), the renal pelvis, and in the kidney itself, although stones are harder to see when located in the mid ureter. Patlas and colleagues reported a sensitivity and specificity of 95% and 93%, respectively, for diagnosing ureteral calculi, although unfortunately a majority of urologists are still ordering CT scans for the workup of renal colic. Stones lodged in the distal ureter are easily seen sonographically either transabdominally through a full bladder, or even better transvaginally. Ureteral calculi are echogenic foci with acoustic shadowing, seen within the lumen of a dilated ureter. There is usually associated ipsilateral hydronephrosis and flank pain. Partial obstruction of the distal ureter may also cause asymmetry of the ureteral jets in the bladder (seen best using color Doppler in the urinary bladder).

Differential Diagnosis

Patients with flank pain who are scheduled for pelvic ultrasound should also have a cursory examination of the ipsilateral kidney. If there is evidence of hydronephrosis, the ultrasound examination should include a careful look at the course of the ureter, including the junction of the distal ureter and the bladder, which is best done transvaginally. If there is a stone at the UVJ, there is essentially no differential diagnosis. Occasionally there may be other disease processes in that location, such as a bladder mass or endometriosis, causing constriction of the distal ureter and mimicking the symptoms of a stone (see Bladder Masses).

Clinical Aspects and Recommendations

Patients with ureteral stones have extreme, crampy flank pain, with tenderness at the costovertebral angle (CVA). Most patients (90%) have gross or microscopic hematuria. The treatment for ureteral stones requires referral to a urologist, who may remove or break up (i.e., lithotripsy) the stone if spontaneous passage does not occur.

Figures

Suggested Reading

Ackerman S.J., Irshad A., Anis M. Ultrasound for pelvic pain II: nongynecologic causes. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am.. 2011;38:69–83.

Masarani M., Dinneen M. Ureteric colic: new trends in diagnosis and treatment. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:469–472 Review.

Patlas M., Farkas A., Fisher D., Zaghal I., Hadas-Halpern I. Ultrasound vs CT for the detection of ureteric stones in patients with renal colic. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:901–904.