Stomach and duodenum

Examination of the stomach and duodenum

Suturing and stapling the stomach and duodenum

Gastrotomy and gastroduodenotomy

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

Elective surgery for peptic ulcer

Billroth I partial gastrectomy

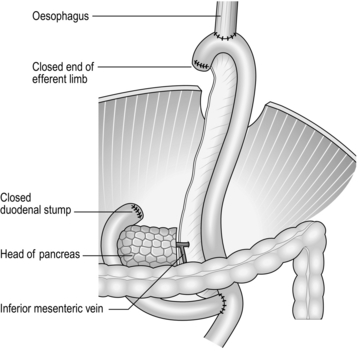

Revision surgery following peptic ulcer surgery

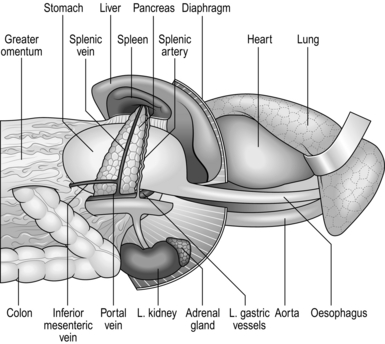

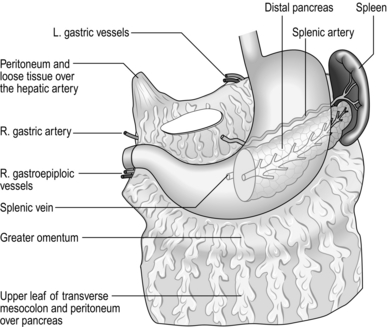

D2 radical abdominal subtotal gastrectomy

Radical thoracoabdominal total gastrectomy

Palliative operations for gastric carcinoma

Proximal gastrectomy or Merendino Procedure (proximal gastrectomy and jejunal interposition)

Palliative partial gastrectomy

Benign and non-epithelial tumours

ENDOSCOPY

Appraise

1. Consider endoscopy when there is a likelihood that tissue biopsy is required. Radiology contrast studies complement endoscopy.

2. Endoscopy is mandatory in the investigation of gastrointestinal bleeding. It is also extremely useful in delineating anatomy, particularly in cases where there has been previous surgery.

3. Endoscopy is also a useful adjunct intra-operatively. It allows for intra-luminal examination if required when the diagnosis remains unclear.

4. The therapeutic capabilities of an endoscope should not be underestimated. Benign strictures can be dilated (bougie or balloon); malignant strictures cored out using Nd-YAG laser; polyps snared and removed; stones removed from the biliary tree; and stents inserted into the oesophagus, pylorus and biliary tree.

5. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomies are commonly performed for patients who are unable to swallow adequate volumes of nutrition. In addition, percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomies and nasojejunal feeding tubes are placed with the aid of endoscopy.

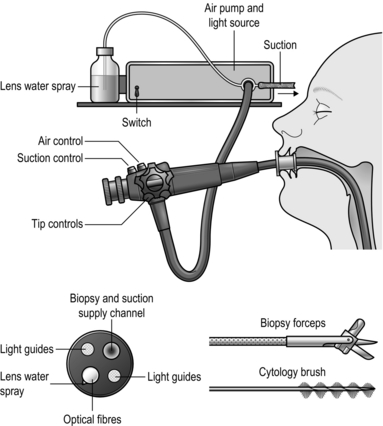

Prepare

1. Familiarize yourself with the endoscopes available in your hospitals. Ensure you are able to set up the scope and the stack independently in case you need to do so out of hours without experienced assistance (Fig. 10.1). Make sure that the instrument, light source, suction apparatus, biopsy forceps and air insufflation pump all work satisfactorily and that the instrument has been sterilized according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Sterilization of instruments during an endoscopy list demands careful organization to guard against transmission of micro-organisms such as Salmonella spp, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Mycobacterium as well as hepatitis B virus (HBV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Thorough cleaning is followed by immersion in 2% alkaline activated glutaraldehyde or 10% succine dialdehyde for a minimum of 4 minutes. Since these substances are toxic, irritant and may cause allergic reactions, the endoscopes must be washed thoroughly afterwards.

Fig. 10.1 Flexible fibreoptic endoscopy.

2. End-viewing endoscopes are most commonly used and are very versatile but side-viewing scopes are used to cannulate the ampulla of Vater.

3. Obtain written, informed consent from the patient, highlighting the indications for the procedure and the potential complications.

4. The patient takes no food or fluids for 6 hours. In an emergency, attempt endoscopy even if the patient has had a recent meal, but there is a higher risk of aspiration. It is prudent to have an anaesthetist in attendance.

5. Don protective gloves and spectacles before starting the procedure.

6. Try to minimize the use and the dose of sedative (midazolam). For simple diagnostic endoscopy, it is often sufficient to use a local anaesthetic throat spray. Monitor all patients using a pulse oximeter and administer oxygen if necessary. Elderly or infirm patients given analgesics and sedatives are at risk of hypoxia, especially during prolonged procedures.

7. Ensure that the patient has no dentures. Insert a plastic mouthpiece between the patient’s teeth or gums through which the instrument will slide easily. Smear the endoscope shaft with water-soluble lubricant. Secretion and mucus are less likely to adhere to the lens if it is smeared with silicone liquid and lightly polished to leave a thin film.

8. The patient may be laid on the left side, with no pillow but with the head steadied by an assistant who maintains neck flexion, discouraging the patient from extending his neck which tends to make the instrument pass into the larynx. The patient’s pronated left hand lies on the right chest, the right hand grasps the edge of the bed. Both knees and hips are flexed. Alternatively, the patient may lie supine but with the head of the bed raised.

Access

1. Slightly flex the tip of the instrument. Pass it through the mouthpiece, over the tongue, keeping the flexed tip strictly in the midline pointing towards the cricopharyngeal sphincter. As the tip reaches the sphincter there is a hold-up. Ask the patient to swallow. The tip will be slightly extruded, and do not resist this, but suddenly the obstruction disappears as the sphincter relaxes and the instrument can be smoothly passed into the stomach after unflexing the tip.

2. Watch the screen and concentrate on safely passing the instrument through the oesophagus and stomach and into the duodenum, noting incidentally if there is any abnormality. Insufflate the minimum of air to open up the passage. Hold and adjust the tip controls with the left thumb and index finger. Hold the shaft of the endoscope with the right hand close to the patient’s mouth, advancing, withdrawing and rotating it as necessary. When the gastric angulus is passed, flex the tip to identify the pylorus. Advance the tip, keeping the pylorus in the centre of the field until the tip slips through.

3. The side-viewing endoscope has a rounded tip which makes it easier to negotiate the pharynx. If there is any doubt about the free passage, always examine the patient first with an end-viewing endoscope. Become familiar with the tip control and angle of view before passing it. When it has passed into the stomach, rotate it to bring into view the relatively smooth, straight lesser curve which ends at the arch of the angulus, below which can be seen the pylorus in the distance. Angle the instrument up towards the roof of the antrum while advancing the instrument. The view of the pylorus is lost momentarily as the tip slips through into the duodenum. Paradoxically, if the shaft is slightly withdrawn, the instrument is straightened and the tip advances further into the duodenum. Rotate the shaft to bring the medial duodenal wall into view and, as the instrument enters the second part of the duodenum, the ampulla of Vater is usually seen as a nipple, often with a hooded mucosal fold above it.

Assess

1. Withdraw the end-viewing instrument in a spiral fashion to bring into view the whole circumference of the duodenum and stomach. Withdraw the side-viewing endoscope whilst rotating it 180° either side to view the whole circumference. Do not overinflate the stomach and duodenum with air. In the duodenum and distal stomach, keep the endoscope still and watch the peristaltic waves form and pass distally, to estimate the suppleness of the walls and exclude rigidity from infiltration or disease. With the tip of the end-viewing instrument lying in the body of the stomach, flex it fully while gently advancing the shaft to bring the fundus and cardia into view (the ‘J’ manoeuvre). Flex the side-viewing instrument to produce the same view. From just above the cardia the end-viewing instrument displays the pinchcock action of the diaphragmatic crura at each inspiration. If gastric mucosa is seen above this, there is a sliding hiatal hernia. The gastric mucosa is pink and shiny; at the crenated transition to the thinner and more opaque oesophageal squamous mucosa, the colour becomes paler and sometimes slightly bluish. Islands of pink gastric mucosa may be seen above the line of transition.

2. If the view disappears, withdraw the instrument and insufflate a little air. If the lens is obscured, clean it with the water jet or wipe it against the mucosa to free it of adherent mucus.

3. Look out for inflammation in duodenitis, gastritis and oesophagitis. As a rule, the mucosa appears florid and reddened, but endoscopy is uncertain and biopsy specimens should be taken when in doubt. In atrophic gastritis the distal mucosa is thinned and translucent so that submucosal vessels are visible through it. In gastric atrophy, associated with pernicious anaemia, the fundic mucosa is particularly affected, being flat and featureless. Menetrier’s hypertrophic gastritis results in strikingly florid mucosal folds, as may the fundic mucosa in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

4. Peptic ulcers usually display a basal slough, but adherent mucosa may simulate a crater. Healed ulcers typically appear flat and white, with radiating mucosal folds. Diverticula, seen usually high on the gastric lesser curve, have healthy mucosa entering the mouth of the diverticulum. Mallory-Weiss tears show a ragged, often bleeding edge in the mucosa at the cardia.

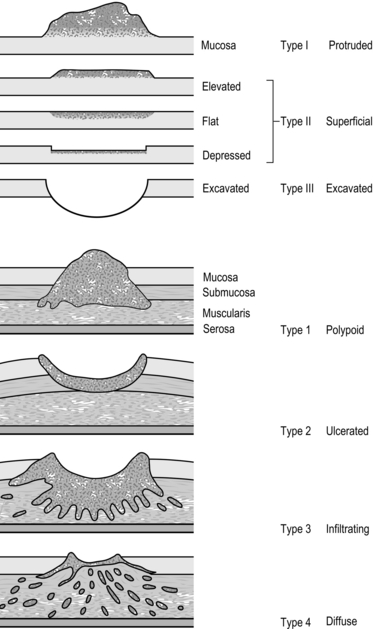

5. Tumours are typically elevated and malignant ulcers have raised, everted edges. Gastric polyps may be single or multiple, and can be mucosal or submucosal, such as leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas, which frequently have healthy mucosa overlying them. Lymphomas – sometimes with mucosal hypertrophy, sharply differentiated from normal mucosa – may reveal no histological abnormality on biopsy, since they tend to spread in the submucosa. They may produce multiple shallow ulcers, or ulcers with raised edges. By the time tumours become obvious they are usually well advanced and the best time to recognize them is in the early pre-invasive stage. Any slight irregularity of the mucosa is suspicious, whether it is a localized depression, plateau, cobblestone irregularity or ulcer, especially if this is an unusual site for a peptic ulcer. In cases of reflux, peptic ulcer disease or dyspepsia remove a sample to be tested for Helicobacter Pylori (Clotest).

6. Oesophageal varices, seen in portal venous hypertension, appear as tortuous, sometimes bluish, projections into the lumen of the lower oesophagus and may continue into the gastric fundus or are occasionally visible only in the upper stomach. Do not assume in patients who have gastrointestinal bleeding that visible varices are necessarily the site of bleeding.

7. Pyloric stenosis may prevent the passage of the instrument into the duodenum and it is sometimes impossible to assess whether the obstruction is from benign duodenal ulceration, a mucosal diaphragm in the distal stomach or neoplastic infiltration.

8. Previous gastric surgery distorts the anatomy and preliminary radiological examination is helpful. A stoma or pyloroplasty allows bile to reflux into the stomach. The mucosa around a stoma is often florid. Stomal ulcers usually develop just distal to the anastomosis and the instrument can be passed through it to view them. Recurrent gastric and duodenal ulcers are usually easy to see but remember that carcinoma occurs more frequently following previous gastric surgery for peptic ulceration.

9. Bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract can often be localized at endoscopy. If possible use an instrument with a wide-bore channel through which efficient suction can be applied. If necessary, rotate the patient to bring the site of bleeding uppermost, so that it is not hidden at the bottom of a pool of blood and other gastroduodenal contents. If the source of bleeding cannot be found, remember that the examination can be repeated. If an operation is to be performed, repeat endoscopy can be carried out just prior to surgery.

10. Always ensure that endoscopy can be repeated during an operation for upper gastrointestinal bleeding. It is sometimes invaluable in locating the bleeding site while avoiding extensive gastrotomy or gastroduodenotomy.

Action

1. Remove biopsy specimens under vision from any suspicious sites, including tumours, the edges of ulcers, irregularities of the mucosa and suspected inflammation. Take specimens from different places, preferably from each quadrant of the edge of an ulcer and not from the sloughy base. If lymphoma is a possibility, take multiple deep biopsies, since the disease often spreads in the submucosa. Place the specimens in carefully labelled separate pots containing formal saline fixative for histological examination.

2. Polypoid lesions can be caught in a snare for removal and histological examination. If the polyp has a broad base ensure that this is completely caught and, if bleeding is likely, coagulate the base with the diathermy before it is removed.

3. Foreign bodies can be grasped with forceps, snared or caught in a modified Dormia basket for withdrawal. An external tube may be slid over and pushed beyond the endoscope tip, enclosing a sharp foreign body as it is withdrawn to protect the mucosa from damage.

4. Bleeding oesophageal varices can be injected under direct vision using sclerosant solution injected through a long needle passed down the biopsy channel (see Chapter 17). Bleeding ulcers may be coagulated by spraying on thrombogenic substances or using the diathermy point. Argon gas laser or a solid state Nd-YAG laser may be used to coagulate the bleeding vessel by energy release at the point of contact. Since laser light is absorbed by blood clot this must first be gently washed away with a fine water jet. The depth of laser penetration is crucial: too superficial and the effect is lost, too deep and the resulting necrosis penetrates the wall. For this reason, laser coagulation must be performed by a skilled, experienced operator.

5. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). A cannula can be passed through a special side-viewing endoscope for insertion in the bile and pancreatic ducts to obtain radiographic pictures following the injection of radio-opaque medium. The ampulla and lower bile duct can be slit with a diathermy wire, and stones can be removed with a modified Dormia basket. A stricture can be dilated from below followed by the insertion of a prosthetic indwelling plastic tube to maintain a passage. These techniques require special training and equipment.

6. Oesophageal dilatation can be carried out with bougies, balloons or by Nd-YAG laser destruction of tissue. The lumen may be held open by inserting a stent (see Chapter 8).

7. Endoscopic ultrasound is a novel diagnostic tool which is most helpful in oesophageal tumour staging but also useful in some gastric pathologies. It also allows for advanced therapeutic manoeuvres such as endoscopic resections of mucosal lesions.

Postoperative

1. Lay a heavily sedated patient in the recovery position (on the left side, slightly face-down), under the care of a trained nurse who will watch him until he recovers fully. If he has any respiratory obstruction this must be overcome; chest physiotherapy will help him to cough up his retained secretions. Do not allow any fluids or foods to be given until the patient is fully recovered and until the effect of pharyngeal anaesthesia has worn off.

PERIOPERATIVE CARE

Preoperative

1. Patients are assessed before an operation and routine check of blood count, blood urea, serum electrolytes and chest X-ray for those who have pre-existing disease, those who smoke or those over 40 years of age is performed. If there is suspicion of cardiac disease, arrange an electrocardiogram (ECG).

2. Explain the intended operation to the patient and obtain informed, signed consent. Detail the risks as well as the benefits.

3. Institute prophylaxis against deep venous thrombosis according to agreed protocol dependent on procedure risk classification.

4. The patient receives no food for 6 hours and water for only 2 hours before operation. If there is evidence of gastric retention, then the stomach should be emptied the day before operation by passing a nasogastric tube for aspiration. Such patients should have an intravenous infusion set up to ensure that they are not dehydrated or electrolytically depleted.

5. Ask the anaesthetist to pass a nasogastric tube as soon as anaesthesia is induced.

6. For straightforward elective operations, some surgeons would not give prophylactic antibiotics, but for emergency surgery such as perforated or bleeding ulcer or surgery for carcinoma or pyloric stenosis give a bactericidal antibiotic, such as a first- or second-generation cephalosporin, before the operation starts and continue it if there is contamination.

Action

1. Although the contents of the healthy stomach are virtually sterile, this is not so in the presence of disease and especially if there is any gastric stasis, as in pyloric stenosis, carcinoma of the stomach and re-operative gastric surgery.

2. Adopt a routine of performing as much dissection as possible before opening the stomach, then isolate the area using added towels of distinctive colour. Keep within the isolated area during the part of the operation that requires the gut to be opened and use a limited number of instruments that are kept separate. Sometimes, in spite of careful preoperative preparation and aspiration of the indwelling nasogastric tube, the stomach is distended with content. In this case, after isolating the area, make an incision into it that will just allow the sucker tube to be inserted and empty it before proceeding; otherwise, the area is likely to be flooded with foul, retained gastric content. Following this, apply non-crushing clamps to occlude the lumen to prevent further efflux. When the stomach or bowel is closed, discard the special towels and the instruments and change into fresh, sterile gloves to continue the operation.

3. The stomach is well supplied with blood and tolerates extensive mobilization without risk to its blood supply. However, this rich blood supply can lead to bleeding from the suture line so consider a haemostatic over-and-over stitch as opposed to a Connell type of stitch, unless the blood vessels are first picked up individually and tied or coagulated.

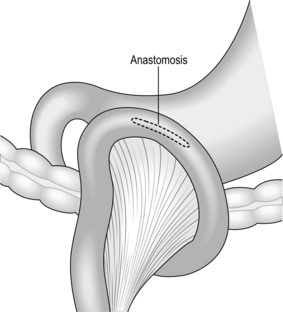

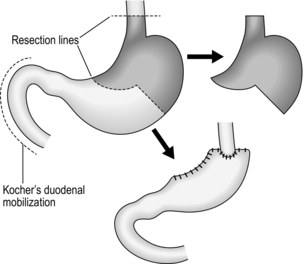

4. The duodenum is fragile and does not tolerate tension or vigorous mobilization. However, the Kocher manoeuvre often renders it mobile and prevents tension (see Fig. 10.3). Rather than anastomose it under tension, be prepared to close it and perform gastroenterostomy if this is possible.

Aftercare

1. Have the patient’s condition monitored carefully until he recovers from the anaesthetic. In particular, note his colour, respiration, pulse rate and blood pressure. The blood pressure is taken every 15 minutes for the first 3 hours and then half-hourly until it is stable. Have the wound checked regularly to ensure that there is no bleeding.

2. See that the urinary output is checked hourly. Following major operations, an indwelling catheter is necessary so that urinary output can be monitored and when an epidural analgesic has been used. It can be removed as soon as the patient has recovered and is active.

3. Order nasogastric tube drainage to be recorded every hour. It may be gently aspirated every 4 hours if there is a high output. If gastric aspirate is recorded as nil, suspect that the tube is either in the wrong place or blocked. Remove the tube when the amount aspirated is less than the oral intake and the aspirate is clear, provided the patient is comfortable, with a soft abdomen. Try to remove the nasogastric tube early in patients with respiratory problems, if necessary restricting oral fluid intake. It is very difficult to cough with a tube irritating the pharynx.

4. Order intravenous fluids, remembering that sodium retention is frequent following operations and that, provided the patient started in fluid and electrolyte balance, only lost electrolytes need be replaced. Provided also that renal function is good, then, if sufficient fluid is given, small imbalances will be compensated. Since enteral feeding is safer and cheaper than parenteral feeding, consider placing a feeding jejunostomy tube or inserting a fine nasoenteric feeding tube at the time of operation in such patients.

5. On the morning after operation, allow 30 ml of water each hour, increasing incrementally to liberal fluid intake on the third day, after which normal intake can be resumed and intravenous fluid replacement stopped. Following many operations, especially when the stomach and duodenum have not been opened, this regime may be speeded up so that the morning after operation the nasogastric tube can be removed and oral fluid intake allowed in increasing amounts, depending on the patient’s tolerance and general condition. Withhold oral fluids following gastric operations with oesophageal anastomosis but allow the patient to have sips as this is no different to swallowing one’s saliva. It is not possible to prevent a little fluid and saliva from being swallowed, but as a rule wait for 4–5 days after operation. It is reasonable to check the intactness and adequacy of the anastomosis radiologically using a water-soluble contrast medium such as Gastrografin before commencing oral fluids and proceeding gradually to full diet. Others do not rely on this test and will start oral intake as long as there are no clinical markers of a leak, such as fever or rising inflammatory markers.

6. Encourage the patient to sit out of bed the morning following operation and have him walking a little during the next day or two, depending upon his general condition. The help of a cheerful physiotherapist in encouraging the patient to cough up retained sputum and move freely is of enormous value in preventing stasis. The use of epidural anaesthesia greatly facilitates such early mobilization.

ACCESS IN THE UPPER ABDOMEN

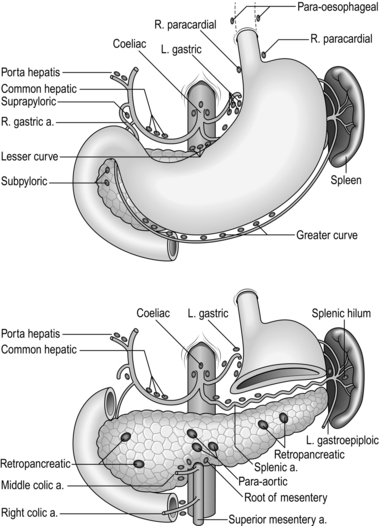

GASTRIC CARDIA

1. Tilt the whole patient in a reverse Trendelenberg position (head up).

2. Use an upper midline incision, opening the peritoneum to one or other side of the falciform ligament. Start the incision at or alongside the xiphoid process and carry it vertically down for 20 cm, skirting the umbilicus.

3. Transverse (rooftop) and oblique incisions are also used but may be restricting in patients with a narrow costal margin. They may also be combined with vertical incisions to form a flap. A rooftop (or inverted ‘V’) incision offers good access since the apex of the ‘V’ can be folded down and sutured to the lower abdominal wall.

4. Carefully place retractors and ensure that the operating theatre light is correctly focused and aimed. To gain access under the diaphragm, use a retractor that elevates the lower sternum and costal margin, attached to a frame fixed to the operating table.

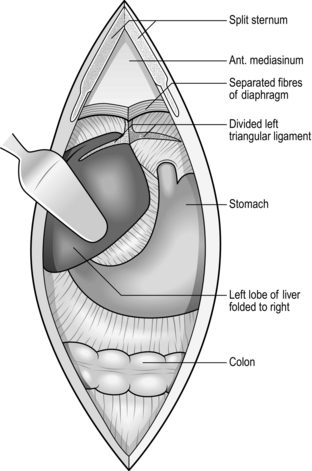

5. Mobilize the left lobe of the liver if this interferes with the view. Insert the fully pronated left hand with the index and middle fingers passing on each side of the left triangular ligament to draw down the lobe. Cut the ligament from its free edge towards the right with long-handled scissors, avoiding damage to the subphrenic vessels and left hepatic veins. Fold the lobe to the right, cover it with a gauze pack and have it held out of the way with a large curved retractor. Remember to replace it carefully at the end of the operation.

6. Carry the whole depth of the incision right up to the xiphisternum or into the angle between it and the costal margin. Do not hesitate to excise the xiphisternum using bone-cutting forceps, after dissecting off the two diaphragmatic muscle slips from its under-surface (Fig. 10.2).

Fig. 10.2 Access in the upper abdomen.

7. If access is still inadequate, particularly for oesophageal anastomosis, consider performing thoracotomy.

8. If using a rooftop incision, make the incision at least an inch below the costal margin to facilitate closure at the end. Make the incision long enough so that you can fold the apex of the V downwards and suture it in the midline below the umbilicus if that helps with exposure.

KOCHER’S DUODENAL MOBILIZATION

Appraise

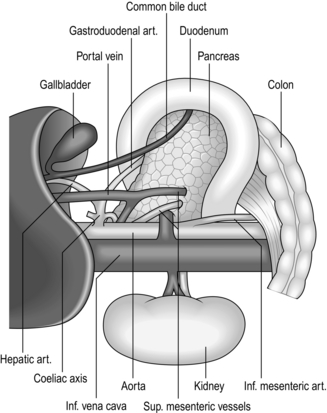

1. This manoeuvre (Fig. 10.3) raises the head of the pancreas contained within the duodenal loop into its embryological midline position, restrained by the structures in the free edge of the lesser omentum above, the superior mesenteric vessels below, and the body and tail of the pancreas to the left.

2. The head and neck of the pancreas can be examined from behind and palpated between fingers and thumb. The lower end of the common bile duct can be palpated and sometimes seen, although it is usually buried within the pancreatic head. The duodenum and especially the ampullary region can be palpated. Duodenotomy allows inspection of the interior of the duodenum. If the incision is placed at the level of the ampulla this can be seen and palpated for tumours or stones. Biopsy, excision of ampullary neoplasms, sphincterotomy, sphincteroplasty, and cannulation or instrumentation of the bile and pancreatic ducts can be carried out under vision.

3. Mobilization is essential for excision of the pancreatic head and duodenal loop in Whipple’s pancreatoduodenectomy.

4. Elevation of the duodenal loop and pancreatic head reveals the inferior vena cava when performing portocaval anastomosis or major hepatic resections.

5. The manoeuvre is particularly valuable in gastroduodenal operations. Pyloroplasty can be performed easily and the extremities of the gastroduodenal incision can be brought together without tension. In gastrectomy, the proximal duodenum is easily dissected and can be closed or united to the stomach with ease. Full mobilization may be a useful step when the stomach is drawn up for gastro-oesophageal or gastropharyngeal anastomosis. However, it is usually the porta hepatis and its connection to the first part of the duodenum that limits further mobilization.

Action

1. If incomplete mobilization is sufficient, as for palpating the lower end of the bile duct or the pancreatic head or for the purpose of carrying out pyloroplasty and gastrectomy by the Polya method, then it may be sufficient to elevate only the superior part of the duodenal loop and pancreatic head. Insinuate a finger into the aditus to the lesser sac and then divide the floor of the foramen downwards, to separate the upper duodenum and pancreas from the inferior vena cava. Extend the mobilization by continuing the division with scissors or diathermy blade, downwards, just outside the convexity of the duodenal loop.

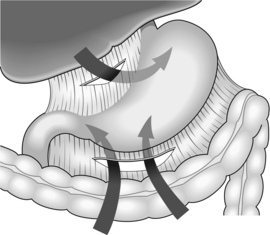

2. For full mobilization, have your assistants draw the hepatic flexure of the colon downwards, the right edge of the wound outwards and the duodenal loop to the left.

3. Incise the peritoneum and underlying fascia of Toldt for 5 cm, placing the incision 1 cm from and parallel to the convex border of the second part of the duodenum.

4. Insinuate your fingers beneath the descending duodenum and pancreatic head. A natural plane of cleavage opens up between the embryological layers which were present when the duodenum was freely suspended in the peritoneal cavity.

5. Having defined the plane, cut the peritoneum and fascia upwards, just outside the duodenal convexity, into the mouth of the aditus to the lesser sac, meanwhile lifting the proximal duodenum forward with a finger, so protecting the inferior vena cava from damage. The dissection is easy and can be carried out by splitting with the finger except in the presence of severe scarring, as from severe duodenal ulceration.

6. Continue the peritoneal and fascial split below, taking care to avoid damaging the right colic vessels, which must be pushed downwards with the hepatic flexure of the colon and mesocolon, to release the junction of the second and third parts of the duodenum.

7. Continue the separation of the pancreas and duodenum across the aorta where it is tethered below by the superior mesenteric artery and its pancreatic branches. The structures in the free edge of the lesser omentum restrain it superiorly.

8. When the appropriate procedure is completed, carefully check the pancreatic head, duodenal loop and the bed from which the structures have been mobilized, before laying them back in place.

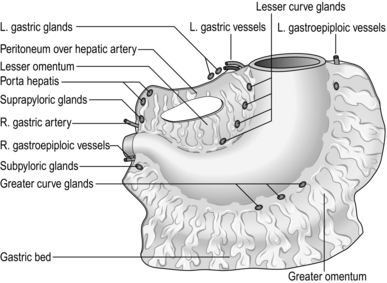

EXAMINATION OF THE STOMACH AND DUODENUM

1. Did you make a firm diagnosis before operation? Mucosal lesions within hollow organs are best assessed from within the lumen by radiology and endoscopy, not by examination of the exterior at operation.

2. Look at the exposed stomach. Is it distended as may be seen in pyloric obstruction? Is the musculature hypertrophied as seen in longstanding partial obstruction? The serous surface may be inflamed and oedematous, or scarred and puckered with petechiae overlying an ulcer. It may be covered with miliary tubercles in tuberculous peritonitis, or metastatic deposits of tumour. The thickened rigid appearance of ‘leather-bottle’ stomach may be accompanied by serosal extension, giving an appearance resembling crystallized sugar adherent to the serosa.

3. Feel for the lower oesophagus and diaphragmatic crura. Sometimes there is an obvious invagination of the gastric cardia through the diaphragmatic hiatus. If the normal anatomy can be restored by applying traction to the lesser curve of the stomach, this is a sliding hiatal hernia. If the cardia cannot be drawn down, there is a fixed hiatal hernia which may be primary or may be secondary to disease in the posterior mediastinum. There may be a gap between the crura into which the fingers can be inserted but the stomach remains fixed within the abdomen. Gently grasp the gastric cardia between finger and thumb and see if it can be slid through the hiatus into the chest. Record an asymptomatic hiatal hernia discovered incidentally when carrying out another procedure but do not repair it. Palpate the fundus of the stomach. If it disappears through the hiatus into the posterior mediastinum, this is a rolling hernia which may cause obstructive symptoms. If the patient has complained of this then consider repairing it, depending upon the severity of the symptoms, the extent of herniation, the fitness of the patient and the severity of the proposed operation.

4. Examine the body and lesser curve of the stomach for evidence of ulcers and ulcer scars. Ulcers and healed scars are often palpable and visible, and former ulcers can sometimes be detected by pinching the stomach along the lesser curve. Normal mucosa can be felt to slip away from your fingers but it may be tethered at the site of a healed ulcer. The stomach can be palpated most readily by making holes through avascular parts of the lesser and gastrocolic omenta so that fingers can be passed behind to feel the two layers of gastric wall against the thumb placed anteriorly (Fig. 10.4). The scar of an undetected posterior gastric ulcer may be adherent to the pancreas, but there are normally flimsy adhesions across the lesser sac between the stomach and pancreas. A pre- or intra-operative endoscopy may be very helpful in confirming mucosal pathology site or anatomical abnormalities. If this is not possible, carry out gastrotomy, preferably in the middle of the anterior wall of the stomach at the level of the suspected ulcer or other lesion and evaginate the lesion through the gastrotomy for visual assessment, biopsy or excision. Alternatively, it can be opened along the greater curvature in order to neither compromise any subsequent resection nor endanger the lesser curve’s integrity if you decide to perform ulcer excision. The gastrotomy may then be closed, either because no further action is necessary or prior to carrying out gastrectomy if a hitherto unsuspected chronic gastric ulcer is causing the patient’s symptoms. In poor-risk patients, gastric ulcer may be treated by ulcer excision. Vagotomy is now seldom used when most patients with benign ulcers can be treated successfully with antibiotics and proton-pump inhibitors.

5. Look and feel for neoplasms. These will in nearly all cases have been diagnosed and thoroughly staged by the TNM system before operation. Staging is by computed tomographic (CT) scanning, endoluminal ultrasound and, often, laparoscopy. Carcinoma is most frequently seen, although lymphoma, reticulum-cell sarcoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST) are not rare, and adenomatous polyps may be felt. Carcinoma may produce a tumour within the stomach or be felt as an ulcer with raised margins. Remember that early gastric cancers may be impalpable.

6. Examine the pyloroduodenal region. The pyloric ring can be picked up between the index finger and thumb of both hands, but the mucosal ring may be smaller than the muscular ring. To check this, invaginate the anterior antral wall through the pylorus on an index finger and invaginate the anterior duodenal wall back into the stomach in a similar manner. If there is obstruction, look again at the stomach. Is it dilated? Is the muscular wall hypertrophied? Look and feel for a duodenal ulcer, remembering that the majority of ulcers lie in the bulb, although they may be in the postbulbar region or further distally, especially in the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. Sometimes an ulcer crater can be palpated, sometimes there is gross and incontrovertible scarring and narrowing, together with pseudo-diverticulum formation but there may be minimal scarring, a few petechial haemorrhages – which could be iatrogenic – or there may be nothing abnormal to see or feel. Of course the diagnosis should have been made endoscopically before operation, but occasionally endoscopy has failed because the tip of the instrument could not negotiate the narrow or distorted pyloroduodenal canal. If doubt remains, could a small endoscope be passed and the tip guided through manually to allow the interior to be viewed? Alternatively, create a small prepyloric gastrotomy and examine the interior with a finger, or by placing small retractors within the pyloroduodenal canal. A mucosal diaphragm that is soft and easily stretched can be dilated, or conventionally treated by pyloroplasty.

7. Diverticula of the stomach are most frequently found on the upper lesser curve, sometimes produced by traction from a leiomyoma. If no primary lesion is present, leave an asymptomatic diverticulum alone. Pseudodiverticula of the duodenum develop when chronic duodenal ulcer causes distortion. The most frequent duodenal diverticulum is not seen unless it is sought for, since it lies close to the ampulla, protruding into the pancreas, which must be mobilized by Kocher’s manoeuvre to approach from posteriorly. It rarely causes symptoms and should normally be left alone.

SUTURING AND STAPLING THE STOMACH AND DUODENUM

SUTURES

1. There is a wide choice of sutures. As with all sutures, they are severely weakened by crushing, abrasion and rough handling, especially when drawing them through the tissues and tying knots.

2. Innumerable papers have been written about the best ways of suturing stomach and intestine. Should we use interrupted or continuous, one layer or two, simple through-and-through or complex stitches, including or excluding the mucosa, inverted or edge-to-edge? It is obvious from listening to, and reading the papers of, the various advocates that all the methods are successful. There is but a single common factor and that is the care with which sutures are inserted and tied. If you bring together the edges of stomach or bowel that have a good blood supply, are not under tension and are apposed carefully with sutures that do not strangulate the included tissue, they will heal. Many of us continue to use the methods we learned whilst training, because they have demonstrably worked, even though we accept that they may no longer be in vogue. The one layer that must always be included in the stitches, as shown by Halsted, is the submucosa.

LIGATURES

As with sutures, ligatures are applied using the finest possible materials, although silk and linen are still popular because of their excellent handling properties. Metal clips are convenient to seal blood vessels but they easily catch in swabs and can be dragged off. One instrument applies two clips side by side and cuts between them, for dividing vascular tissue. Unless they offer advantages in saving time, prefer to tie ligatures, which is more versatile.

As with sutures, ligatures are applied using the finest possible materials, although silk and linen are still popular because of their excellent handling properties. Metal clips are convenient to seal blood vessels but they easily catch in swabs and can be dragged off. One instrument applies two clips side by side and cuts between them, for dividing vascular tissue. Unless they offer advantages in saving time, prefer to tie ligatures, which is more versatile.

Absorbable synthetic clips have also become more commonly used.

Absorbable synthetic clips have also become more commonly used.

STAPLES

The development of reliable instruments for joining bowel has potentially great value in gastroduodenal surgery. However, they are not as versatile as sutures. If you are a trainee, by all means learn to use stapling instruments but more importantly take every opportunity to master the accurate placement of sutures.

The development of reliable instruments for joining bowel has potentially great value in gastroduodenal surgery. However, they are not as versatile as sutures. If you are a trainee, by all means learn to use stapling instruments but more importantly take every opportunity to master the accurate placement of sutures.

There are two overriding indications for using stapling instruments. The first is when the difficulties of suturing, perhaps because of inadequate access that cannot be improved, make stapling safer. The second is when speed is essential, perhaps during a major operation.

There are two overriding indications for using stapling instruments. The first is when the difficulties of suturing, perhaps because of inadequate access that cannot be improved, make stapling safer. The second is when speed is essential, perhaps during a major operation.

Gastrotomy and gastroduodenotomy

Appraise

1. Gastric, gastroduodenal and duodenal incision allows the interior of the bowel to be examined to confirm, biopsy or treat a suspected lesion such as an ulcer, tumour or source of bleeding.

2. Gastrotomy allows access from below to the lower oesophagus. Strictures are often dilated more safely from below than from above.

Access

1. As a rule, open the stomach on the anterior wall midway between the greater and lesser curves.

2. For the purpose of diagnosis, start with a small incision, 3–4 cm long, the proximal end of which is 5–6 cm from the pylorus. This incision ensures that the intact pylorus or mucosal diaphragm can be examined and it may be unnecessary to destroy the pyloric muscular ring. The incision can be extended proximally or, if it becomes necessary, distally through the pyloric ring onto the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb.

3. To view the interior, first aspirate all the contents. Retractors may be placed to hold open the stomach so that it can be examined by adjusting the theatre light to shine through the opening. The stomach can be manoeuvred manually to bring different parts of the interior into view. Frequently the gastric wall can be evaginated through the incision so that it can be examined and any lesion excised or biopsied. If the pylorus is not too narrow, small retractors may be placed in to allow the duodenal bulb to be viewed, and, if it is wide, an unscarred duodenal bulbar wall may be evaginated through it on a finger. If there is difficulty in viewing the duodenum to exclude or confirm disease, a per-oral endoscope may be introduced through it. Sometimes, when fibreoptic endoscopy is ineffective before operation, perhaps resulting from inability to evacuate the gastric contents, the stomach may be emptied and endoscopy can then be performed. The gastrotomy can be temporarily occluded with a clamp to allow the stomach to be inflated but as a rule the stomach can be held open to allow endoscopy to be accomplished without the need for inflation.

Closure

1. Close a gastrotomy in one or two layers, leaving a longitudinal suture line.

2. It is conventional practice to close a gastroduodenotomy as a Heineke-Mikulicz pyloroplasty. This may be accomplished using a single edge-to-edge row of sutures, a two-layer invaginating suture or with a row of staples. However, this destroys the pyloric metering function and it may be preferable to carefully close the incision to create a longitudinal scar, bringing the edges together without invagination in a single layer, taking care to appose the pyloric edges perfectly. Cover the suture line with a layer of omentum as an extra precaution.

3. Use ingenuity to incorporate the gastrotomy in plans for other procedures. A distal gastrotomy may be incorporated in a gastroenterostomy. The proximal part of a long gastroduodenotomy may be closed longitudinally and the distal part converted into a pyloroplasty if necessary. If gastrectomy is intended, temporarily close the gastrotomy with stitches or staples to keep soiling to a minimum.

PYLOROMYOTOMY

Appraise

1. Pyloromyotomy for infantile pyloric stenosis is described in Chapter 34.

2. Adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is rarely discovered as a cause of gastric retention. It is not known whether or not this represents undiagnosed infantile pyloric stenosis.

3. Pyloromyotomy is sometimes carried out following oesophagectomy with oesophagogastric anastomosis, in the hope of preventing gastric retention. Failure of the stomach to empty in the absence of pyloric stenosis results from gastric atony following the inevitable gastric vagotomy. Many surgeons employ a pyloroplasty to compensate for this postvagotomy gastric atony.

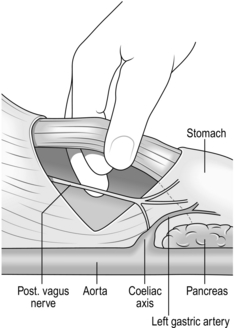

Action

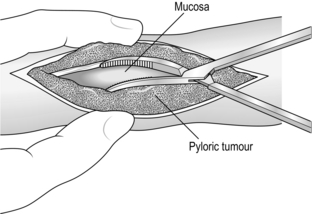

1. Grasp the pylorus between finger and thumb of the left hand to steady it (Fig. 10.5).

Fig. 10.5 Pyloromyotomy.

2. Incise the seromuscularis along the middle of the anterior antral wall from 1 cm proximal to the thickened segment and carefully extend it distally across the pylorus onto the anterior duodenal wall for 1 cm. The duodenal wall at the fornix is very thin, so take care not to incise into the lumen.

3. Deepen the incision through the thickened muscle of the distal antrum until the mucosa bulges into the split. Make sure all the muscle fibres are divided. The final split may be accomplished by grasping the wall on each side of the split with dry gauze swabs and separating the edges, to allow mucosa to bulge freely along the whole of the incision.

4. Carry the split distally to the pylorus and carefully divide all the circular muscle fibres here, again taking care to expose but not damage the mucosa of the first part of the duodenal bulb. Lift the muscle fibres free of the mucosa with closed fine non-toothed dissecting forceps, allow the forceps blades to open and then cut the fibres between them.

Check

1. Make sure all the fibres have been cut.

2. Gather some gastric air into the segment with the pyloromyotomy, to distend the mucosa so that it bulges into the split. Watch carefully for any leaks. It is no disaster to find a leak and carefully close it with fine stitches: it may be disastrous to miss a leak.

OPERATIVE GASTROSTOMY

Appraise

1. Gastrostomy offers a valuable method of feeding patients who are unable to swallow because of oesophageal obstruction, bulbar palsy and other causes. Patients with mechanical obstruction who will have reconstructive surgery utilizing the stomach as a conduit should not normally have a temporary gastrostomy since this will interfere with subsequent reconstructive surgery. They are better served by a jejunostomy.

2. Gastrostomy offers a means of providing gastric aspiration without nasogastric intubation, valuable in patients who have respiratory difficulties and those who cannot tolerate the presence of the tube in their pharynx, during the postoperative recovery period from gastric operations.

3. As a rule gastrostomy is placed endoscopically (Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy – PEG) and is intended as a temporary measure. When all else fails, do not hesitate to offer it after discussion with the patient.

4. Operative gastrostomy is often unnecessary following the advent of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. If necessary, a number of operative techniques have been described. Stamm’s gastrostomy (Fig. 10.6) is almost universally used now and is described below. The tube passes through the abdominal wall and enters the stomach through a small stab wound. The hole is prevented from leaking by invaginating it using a series of purse-string sutures so that it resembles a non-spill inkwell. Witzel’s gastrostomy is similar, but leakage is prevented by laying the emerging tube along the stomach wall and covering it by suturing over it ridges of gastric wall so that it lies in a tunnel. The Depage-Janeway gastrostomy employs a flap of stomach formed into a tube which is brought to the skin surface to create a permanent conduit.

Fig. 10.6 Stamm gastrostomy.

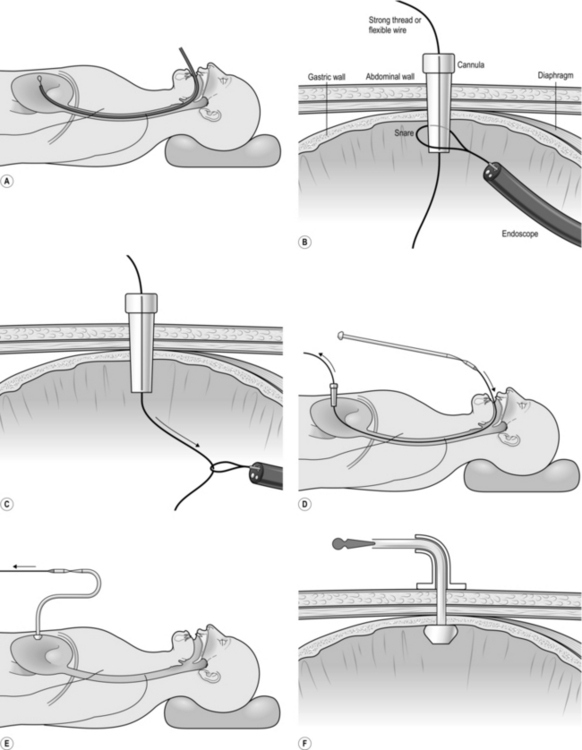

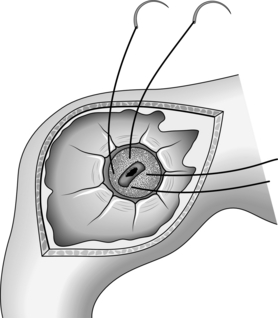

PERCUTANEOUS ENDOSCOPIC GASTROSTOMY

Appraise

1. The commonest application is for intragastric or enteral nutritional support in the presence of, for example, bulbar palsy. Another indication is to enable prolonged gastric aspiration to be performed, especially in those who cannot tolerate nasogastric intubation.

2. Do not attempt this method if the patient has an impassable oesophageal stricture, or previous upper abdominal surgery that produces adhesions preventing expansion of the stomach to contact the anterior abdominal wall, or a partial gastrectomy. Gross ascites or sepsis makes the procedure dangerous so a surgical gastrostomy or jejunostomy is preferred. Portal venous hypertension, coagulopathy/gastric ulcer or tumour at the elective site of gastrostomy is also a contraindication. Gross obesity may make the procedure difficult.

3. There is a choice of methods, and some excellent commercially produced kits are available with tubes 9F or 15F in size. A popular, simple pull-through technique is described below.

Action

1. Pass an end-viewing endoscope into the stomach. In the presence of an oesophageal stricture it may be necessary to dilate it using bougies or a balloon, and then introduce a paediatric endoscope. Pass the tip into the distal stomach.

2. Inspect the stomach and duodenum to exclude any condition that would contraindicate gastrostomy.

3. Gently inflate the stomach to distend it.

4. Have the abdomen exposed and the room lights dimmed.

5. Turn the endoscope tip towards the anterior abdominal wall. The light should be visible through the gastric and abdominal walls.

6. Have the abdominal operator indent the anterior abdominal wall with a finger placed where the endoscope light is seen most brightly. The indentation should be visible from within the stomach.

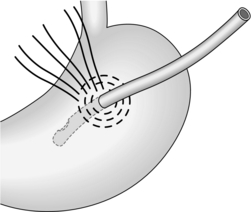

7. Pass a polypectomy snare through the biopsy channel of the endoscope (Fig. 10.7A).

8. If you are the abdominal operator, prepare the skin, infiltrate the chosen puncture spot with local anaesthesia into the skin and abdominal wall (and most often into the gastric lumen under direct vision), then make an incision in the skin sufficiently large to allow the passage of the gastrostomy tube.

9. Pass a needle carrying a smooth, closely fitting plastic cannula through the abdominal wall into the stomach. This catheter is usually in the PEG kit but a standard intravenous catheter may be employed.

10. If you are the endoscopist, manoeuvre the loop of the snare over the cannula (Fig. 10.7B). The needle is withdrawn by the abdominal operator and either a flexible wire or a strong thread is passed through the cannula into the stomach.

11. Withdraw the snare from the end of the cannula under vision, in order to grasp the thread or wire that protrudes from the end of the cannula into the stomach (Fig. 10.7C). While the abdominal operator holds the other end of the thread or wire, withdraw the endoscope, snare and trapped thread or wire out through the mouth.

12. Attach the emerging thread or wire to the tapered end of the gastrostomy tube (Fig. 10.7D). The bulbous or inflatable end of the gastrostomy tube will remain in the stomach, pulling it against the abdominal wall.

13. Apply lubricant to the gastrostomy tube.

14. Draw upon the thread or wire emerging from the abdominal cannula while guiding the tapered tip of the gastrostomy tube through the patient’s mouth and into the oesophagus and stomach. Eventually the tapered tip is drawn against the cannula tip, extruding it. As you continue to pull, the tapered end of the gastrostomy tube will emerge through the gastric and abdominal walls (Fig. 10.7E).

15. Re-pass the endoscope into the stomach and observe the enlarged end (‘bumper’) of the gastrostomy tube as it is drawn up against the gastric wall. In some tubes the end is shaped so that it expands automatically; in others, a balloon is expanded by distending it with air or fluid through a side channel. Make sure that the tension on the gastrostomy tube is not sufficient to cause gastric mucosal blanching.

17. Cut off the tapered end of the gastrostomy tube and ensure that the expanded end is inflated if it is of this type, and seal the side-tube inflation channel.

18. The tube must be fixed to hold the stomach against the abdominal wall. Most kits contain a fixation base that fits over and holds the gastrostomy tube, having an expanded flat surface that lies against the abdominal wall (Fig. 10.7F).

Aftercare

1. Feeding with suitable varied fluids can usually start within 24 hours.

2. Monitor the patient to ensure that there is no chest infection, since reflux and aspiration pneumonia is a well-recognized complication.

3. Check the gastrostomy site since infection is frequent.

4. Leakage around the gastrostomy catheter may develop spontaneously or in the presence of gastric outlet obstruction.

5. Some gastrostomy tubes can be removed by deflating the expanded end and drawing them through the abdominal wall. Others require endoscopic withdrawal.

PERFORATED PEPTIC ULCER

Appraise

1. Record the patient’s age, blood pressure and the presence or absence of serious associated disease such as cardiac, respiratory or renal failure. Fully resuscitate the patient before performing the operation.

2. Perforation of other viscera such as colon or gallbladder may be confused with gastroduodenal perforations. A laparoscopic approach may aid diagnosis and may be adequate for treatment. A CT scan is vital in making a clear diagnosis as long as the patient is stable enough to go through the scanner.

3. Not all patients who have a perforated peptic ulcer should have an operation. Patients seen within 8 hours, in whom a confident diagnosis is made, and who are haemodynamically stable, may be treated conservatively. Ensure that the tip of an 18F nasogastric tube is accurately placed in the most dependent part of the stomach. A disadvantage is that peritoneal toilet cannot be performed. Proceed to operation at once if the patient develops pyrexia, tachycardia, pain, distension or increasing intra-peritoneal gas on X-rays. A few patients develop intra-peritoneal abscesses if there has been significant leakage and soiling. Nasogastric suction, parenteral feeding, systemic antibiotics and chest physiotherapy are instituted, and operation is resorted to only if the patient fails to improve or deteriorates.

4. Perforated gastric ulcer carries a higher mortality than perforated duodenal ulcer, because the patients are, on average, older and generally less ‘fit’. Most gastric ulcer perforations are successfully managed by simple suture after excising a specimen from the edge for histology. Sometimes they are difficult to close and demand gastrectomy. If there is doubt about the nature of the ulcer, treat it as though it is benign, remove a biopsy specimen from the edge and, if malignancy is demonstrated histologically, carry out the appropriate operation later as an elective procedure. If the ulcer cannot be sutured but is of doubtful origin and frozen-section histology is equivocal or cannot be arranged, then carry out gastrectomy as for a benign ulcer and be prepared to re-operate to carry out an elective radical procedure later. The added risks of performing a radical operation are not justified without confirming the diagnosis.

5. Bleeding associated with perforation demands control of both complications. A bleeding perforated gastric ulcer is conventionally controlled by distal gastrectomy, including the ulcer. Bleeding is rarely a complication of anterior perforating duodenal ulcer but if there is a co-existent bleeding posterior duodenal ulcer, the anterior perforation can be incorporated into a gastroduodenotomy. Insert non-absorbable stitches into the base of the posterior ulcer to control the bleeding and then close the gastroduodenotomy as a pyloroplasty. If unable to close the duodenotomy due to friable tissue then perform a distal gastrectomy, close the duodenal stump over a Foley catheter balloon (exteriorized as a controlled fistula) and place a large surgical drain next to the stump. These patients need long-term proton-pump inhibitors.

6. Perforated gastric carcinoma may be amenable to the same operation as would be carried out electively. If not, consider suturing it or plugging the defect with omentum and re-operating electively later after the patient has been brought to the best possible condition. Sometimes inadequate resection is forced upon the surgeon. If so, consider whether this can be corrected later by a more adequate operation.

7. Laparoscopy may be used to confirm the diagnosis, followed by repair using sutures, staples or a plug.

Assess

1. Remove all instruments from the field with the exception of a retractor for your assistant and the sucker tube for yourself.

2. Aspirate any free fluid after collecting a specimen for laboratory examination. Gastric juice is usually bile-stained.

3. Examine the duodenal bulb and the stomach, especially along the lesser curve. If necessary, open the lesser sac of omentum through the lesser or gastrocolic omenta to view the posterior gastric wall.

4. Remember that multiple perforations can occur.

5. Always locally excise or remove a biopsy specimen from the edge of a gastric ulcer.

6. If you cannot find the perforation after a diligent search, explore the whole abdomen, if necessary extending the incision downwards. Examine in particular the gallbladder and sigmoid colon. If you are still puzzled, consider the possibility of Boerhaave’s syndrome (spontaneous rupture of distal spontaneous oesophagus).

7. If you are a surgeon in training and find yourself in difficulty either because of failure to discover the cause, or indecision about the best course of action, or because the required procedure is beyond your capabilities, do not hesitate to contact your chief for advice and assistance.

Simple closure

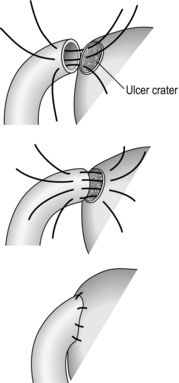

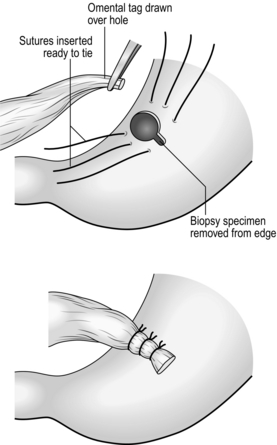

1. Place two or three parallel sutures of 3/0 synthetic absorbable material through all coats, passing in 1 cm proximal to the ulcer edge and emerging 1 cm distal to the ulcer (Fig. 10.8). Do not pick up the opposite wall as this will obstruct the lumen. When all the sutures are in place, mobilize a tongue of omentum, place it over the perforation and tie the sutures just tightly enough to hold it in place.

Fig. 10.8 Suture of a perforated peptic ulcer.

2. Insert further sutures to reinforce the obturating action of the omentum and ensure the defect is adequately sealed.

3. Even when closure seems secure, do not hesitate to suture omentum over it.

4. Aspirate any free fluid from above and below the liver, from within the lesser sac, the right paracolic gutter and from the pelvis.

ELECTIVE SURGERY FOR PEPTIC ULCER

Appraise

1. Medical treatment has become the mainstay with potent antacids, atropine-like drugs, liquorice extracts, mucosal-coating substances, histamine H2-receptor-blocking drugs and proton-pump inhibitors. The elimination of Helicobacter pylori, using so-called triple therapy of a proton-pump inhibitor combined with two antibiotics such as clarithromycin and metronidazole, reduces the relapse rate. Most patients can be controlled with these powerful and safe agents and the only people who may require operation are the minority who cannot be controlled medically, who cannot or will not take the required treatment, or who develop complications of the ulcer.

2. The operation in vogue in the 1960s and 1970s was proximal gastric vagotomy, known also as highly selective vagotomy. Some centres report high rates of recurrence after long-term follow-up but variations in recurrence rates probably reflect variations in completeness of parietal cell denervation and are thus dependent on the skill of the surgeon. An adjunctive operation to overcome gastric retention is unnecessary if there is no evidence of impending pyloroduodenal stenosis resulting from the chronic ulcer scarring. If there is, some surgeons dilate the canal through a prepyloric gastrotomy using Hegar-type dilators or a finger, or by invaginating the anterior duodenal and gastric antral walls through the stenosed canal on an index finger tip – a manoeuvre introduced by Jaboulay. If the stenosis is confined to the bulb, a longitudinal incision can be made through it without impinging on the pyloric ring, closing it as a transverse suture line after the manner of a pyloroplasty; hence it is termed a duodenoplasty. A few surgeons still prefer truncal vagotomy combined with pyloroplasty, gastroenterostomy or distal gastrectomy to improve gastric emptying.

3. Gastric ulcer was treated more aggressively by surgeons in the past than was duodenal ulcer. Many surgeons adopt a fixed policy of carrying out endoscopy and biopsy to confirm that the ulcer is benign, then give the patient a 6–8-week course of medical treatment followed by a further check endoscopy. If the ulcer is healed, operation is deferred. If the ulcer is not healed, or if it soon recurs, then surgical treatment is recommended. This more aggressive treatment stems partly from anxiety about the possibility of early malignancy or impending change and partly from the pragmatic knowledge that chronic gastric ulcers are less likely than chronic duodenal ulcers to become quiescent.

4. Postbulbar duodenal ulcers are quite frequently seen in certain countries, especially southern India, but are relatively uncommon in Western countries. They are often severe and stenosing so that operation may be recommended for fear of incipient obstruction. Proximal gastric vagotomy is effective if the lumen is still widely patent; if it is not then add gastroenterostomy, thus retaining the vagal supply to the gallbladder, pancreas and small intestine.

5. Zollinger-Ellison syndrome associated with hypergastrinaemia, usually from G-cell hyperplasia or gastrin-secreting tumour in the pancreas, generally produces peptic ulcers in usual sites. If an ulcer lies in an unusual site, or if there are multiple ulcers and especially if the ulcer is in the upper jejunum, suspect the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (vide infra).

6. Oesophageal peptic ulceration occurs when gastric acid refluxes into the oesophagus where the squamous mucosa is unresistant to acid attack. This develops most frequently as a result of hiatal hernia but can occur in the absence of herniation of the stomach into the chest. A less frequent cause of peptic ulcer in the oesophagus is the condition of Barrett’s oesophagus. This appears to be acquired, although it used to be called ‘congenitally short oesophagus’. There is intestinal metaplasis in the distal oesophagus and the oesophagogastric mucosal junction moves progressively upwards; an ulcer sometimes develops just above the junction. There is a greatly increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the distal oesophagus (see Chapter 9).

VAGOTOMY

TRUNCAL VAGOTOMY

Appraise

1. Per-hiatal truncal vagotomy was formerly indicated for the management of uncomplicated duodenal ulcer when the full range of medical treatment had been tried and failed to control the symptoms. It is normally accompanied by pyloroplasty or gastroenterostomy to improve the rate of gastric emptying, so-called drainage procedures. Pyloroplasty (vide infra) is simple to perform unless the patient is very obese with a deep abdomen and with a fixed, very scarred pylorus. Anterior juxatapyloric gastroenterostomy is convenient if pyloroplasty is difficult to perform, and has the advantage that it is not irrevocable.

2. Truncal vagotomy may be used when controlling gastroduodenal bleeding from peptic ulcer. At such operations the main task is to stop the bleeding, but the secondary task is to prevent bleeding from recurrent or persistent ulcer.

3. In the surgical management of recurrent peptic ulcer truncal vagotomy is best combined with partial gastrectomy.

4. Truncal vagotomy combined with a ‘drainage’ operation is sometimes advocated for the definitive management of a perforated duodenal ulcer. The improvement in medical management of uncomplicated duodenal ulcer has rendered this approach obsolete.

5. Truncal vagotomy and a drainage operation is often effective treatment for chronic gastric ulcer in an unfit patient, but gastrectomy including the ulcer is preferred treatment whenever possible.

Access

1. Use a midline incision 20 cm long, skirting the umbilicus.

2. Mobilize the left lobe of the liver, folding it to the right, to obtain a good view.

3. In an obese patient with a high diaphragm try the effect of tilting the patient 25–30° head-up.

4. Insert a retractor fixed to the table, to elevate the sternum.

Assess

1. Explore the whole abdomen. Remember that patients with proven peptic ulceration may have incidental conditions such as gallstones or colonic carcinoma which might help to explain their symptoms.

2. Examine the stomach and duodenum and note the effects of the ulcer in distorting the duodenum and fixing it, so that you may make a decision about the easiest and safest adjunctive operation.

Action

1. Make sure there is a nasogastric tube in place, as a guide to the line of the gullet at the oesophageal hiatus.

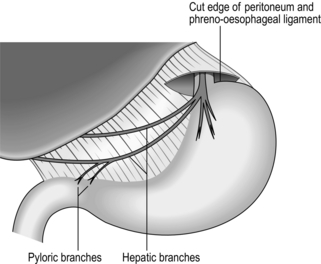

2. While an assistant grasps the lower anterior wall of the stomach and draws it down, identify the hiatus by feeling for the nasogastric tube. Open the peritoneum transversely, avoiding the inferior phrenic vessels. Beneath this is the phreno-oesophageal ligament. Open this and enlarge the incision to 3–4 cm. You can now pass the closed scissors anterior to the gullet into the posterior mediastinum. If you cannot, you have not yet opened the phreno-oesophageal ligament. Thorough mobilization of the distal oesophagus is the key to the achievement of complete vagotomy.

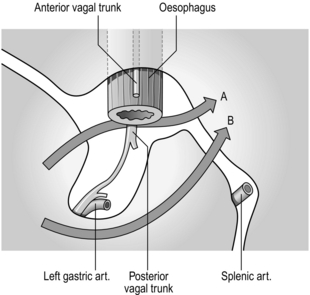

3. Look out for the anterior vagal trunk lying in front of the oesophagus (Fig. 10.9) and separate it upwards for 5 cm and downwards to where it gives off the hepatic and gastric body branches, continuing as the anterior nerve of Latarjet. Transect it where it breaks up below, crushing the distal stump to occlude the small vessels running with it. Place a curved Moynihan clamp across it as high as possible and transect it just below the clamp, then remove the clamp. This is a ‘vagectomy’ and ensures that the whole trunk is removed but does not guarantee that vagotomy is complete, since fine branches may come off higher up and bypass the ‘vagectomy’.

Fig. 10.9 Truncal vagotomy. Exposure of the anterior nerve; the distribution of the nerve is indicated.

4. Encircle the lower gullet with the right forefinger and thumb. There is a ‘mesentery’ behind the gullet in which lies the posterior vagal trunk (Fig. 10.10). Pass the middle finger to the left of the gullet and push this ‘mesentery’ to the right so that the nerve trunk can be identified. Separate the oesophagus from the vagus and burst through the mesentery behind the vagus. As the trunk is traced down, part of it passes backwards to the coeliac plexus (Fig. 10.11), part continues downwards as the posterior nerve of Latarjet and branches leave to reach the body of the stomach. Crush and cut the nerve below and again as high as possible to remove a segment of nerve to insure against leaving a separate branch intact.

5. Search for missed, separate branches around the whole circumference of the oesophageal wall. They feel like tight threads and should be divided. Make sure that there is no damage to the oesophagus and that all the bleeding is controlled.

6. Repair the horizontal defect in the hiatus using non-absorbable sutures.

7. Carry out the selected adjunctive procedure of pyloroplasty, gastroenterostomy or gastrectomy.

PROXIMAL GASTRIC VAGOTOMY

Appraise

This operation is otherwise known as highly selective vagotomy.

This operation is otherwise known as highly selective vagotomy.

Proximal gastric vagotomy aims to denervate only the acid-secreting proximal part of the stomach, leaving the alkali-secreting antrum, with its muscular pumping action, still innervated. Thus gastric acid secretion is reduced but gastric emptying is usually unimpaired. The addition of a drainage operation can be dispensed with in most patients in the absence of pyloroduodenal stenosis.

Proximal gastric vagotomy aims to denervate only the acid-secreting proximal part of the stomach, leaving the alkali-secreting antrum, with its muscular pumping action, still innervated. Thus gastric acid secretion is reduced but gastric emptying is usually unimpaired. The addition of a drainage operation can be dispensed with in most patients in the absence of pyloroduodenal stenosis.

Action

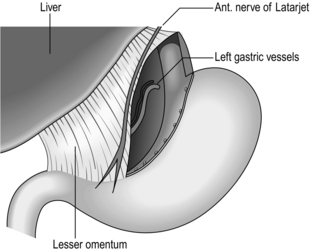

1. Make a hole through an avascular area in the mid-portion of the gastrocolic omentum. While the stomach is lifted forwards, carefully and completely separate the flimsy attachments of the stomach to the pancreas, watching out for, and preserving, the fold of peritoneum that contains the left gastric vessels. Separate the stomach from the posterior wall right up to the roof of the lesser sac. Occasionally you will be surprised to find the scar of an unsuspected posterior gastric ulcer.

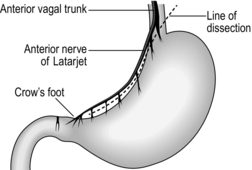

2. Pass the right index finger through the hole in the gastrocolic omentum and grasp the gastric antrum to draw it down, so stretching the lesser curve of the stomach. In all but the most obese patients the taut anterior nerve of Latarjet can be seen running parallel to the lesser curve, separating into branches which form a ‘crow’s foot’ pattern as they cross the curvature at the angulus, accompanied by blood vessels from the descending branch of the left gastric artery (Fig. 10.12). The posterior nerve cannot usually be seen from the front but can be displayed by looking through the hole in the gastrocolic omentum after turning the stomach forwards and upwards.

3. Carefully make a hole through the lesser omentum close to the gastric wall, just to the left of the ‘crow’s foot’ of nerves, while protecting the posterior structures from damage with the right index finger passed through the defect in the gastrocolic omentum. Pass one end of a tape through the hole in the lesser omentum, drawing it out through the hole in the gastrocolic omentum. The tape now encircles the stomach at the level of the angulus, marking the lower limit of dissection. Clip the ends of the tape together so they may be used to exert gentle downward traction on the stomach by an assistant to tauten and define the nerves of Latarjet.

4. Make a second, higher hole in the lesser curve close to the stomach just above the next visible vessels. Double-clamp, divide and ligate the vessels and accompanying nerve filaments.

5. A better method is to pass double ligatures with an aneurysm needle or with Lahey’s fine curved forceps, tie them carefully and divide the tissue between them. It is possible to use haemostatic clips instead of ligatures. One instrument applies two clips side by side and cuts between them: there is not usually sufficient tissue but it may be carefully used where the vessel and nerve length is adequate. If you do use haemostatic clips, take care that you do not inadvertently brush them off, thus tearing the delicate blood vessels.

6. Proceed upwards step by step, dividing the vessels and nerves that cross the lesser curve, carefully preserving the nerves of Latarjet as they are separated from the stomach. Higher up on the stomach, the vessels and nerves do not tend to penetrate at the lesser curve but cross it to enter on the posterior or anterior wall. Take advantage of this extra length by carrying the dissection onto the anterior and posterior walls. The separation of the anterior and posterior nerves of Latarjet from the stomach now proceeds independently onto the anterior and posterior gastric walls.

7. As the anterior and posterior layers of lesser omentum separate, slide non-toothed forceps under avascular sections and cut between the opened blades. Small vessels may be sealed with low-power diathermy applied for the minimum time through fine forceps applied well away from the main nerves and from the gastric musculature.

8. At the level of the main left gastric artery and vein quite large vessels must be ligated and divided on the anterior and posterior walls, together with their accompanying nerve filaments. Above these, the lowest portion of the oesophagus can be separated from the nerves of Latarjet without dividing any large vessels.

9. As the dissection reaches the cardia, the main trunks of the nerve are separated from the gullet, the nerves of Latarjet being the inferior prolongations of them. At this point temporarily stop the dissection.

10. Draw down the gastric fundus while an assistant retracts the left costal margin. Identify the angle of His between the fundus and the left edge of the lower gullet. Carefully incise the peritoneum in the angle, without damaging the stomach or oesophagus. Open up the hole gently with the right index finger and pass the right thumb through the upper part of the defect in the lesser omentum, behind the fundus of the stomach. Thumb and finger are prevented from meeting by the peritoneum of the roof of the lesser sac, which can now be broken through.

11. At the level of the cardia separate, doubly ligate and divide the peritoneum, phreno-oesophageal ligament and nerve fibres across the anterior aspect of the lower oesophagus, leaving the muscle coat denuded but intact.

12. Divide loose tissue and nerve fibres around the posterior aspect of the lower oesophagus, rotating it to improve the view. A troublesome fragile vein is encountered, running posteriorly from the cardia, often in a crescentic peritoneal fold. Tie it, seal it with diathermy current or apply a haemostatic clip. Do not encroach more than 2 cm on the greater curve aspect of the gastric fundus or you will damage the short gastric vessels and the spleen.

13. Clear the whole circumference of the lower 5–7 cm of the oesophagus of nerve fibres. Do not damage the longitudinal muscle coat. Catch any small veins that have retracted into the muscle coat using fine sutures if necessary (Fig. 10.13).

Checklist

1. Examine the lesser omentum, lesser curve of stomach, lower oesophagus and upper lesser sac for signs of damage or bleeding. Have the short gastric vessels or spleen been damaged?

2. Re-examine the lower oesophagus for the presence of persistent vagal fibres and for signs of damage to the muscular coat. Re-examine the incisura angularis, where vagal fibres to the parietal cell mass may also have escaped detection. Finally, look again at the gastric lesser curve to ensure there is no damage. Ensure that 5–6 cm of distal stomach remains innervated.

PYLOROPLASTY

Appraise

1. Re-formation of the pylorus has the effect of increasing the size of the lumen and also destroys the pyloric sphincteric metering function. It can be used to overcome stricture of the pylorus and also to improve gastric emptying following truncal vagotomy. Following proximal gastric vagotomy, the distal stomach or ‘antral mill’ remains innervated so that gastric emptying is not usually prejudiced and pyloroplasty is not required.

2. Pyloroplasty is simple to perform in most circumstances and has enjoyed great popularity as an adjunctive operation with truncal vagotomy for duodenal ulcer. It may be difficult to perform if the duodenum is very scarred and adherent to the pancreas and the structures in the free edge of the lesser omentum if the abdomen is obese and deep.

3. It is probable that many postvagotomy symptoms are attributable to the drainage procedure and not to the vagotomy. Many such patients are improved if the drainage procedure is reversed. Although the pylorus can be anatomically restored to normal, the long-term results are not impressive.

4. Inevitably a number of methods of performing pyloroplasty have been described. The Heineke-Mikulicz method is the simplest, but some surgeons favour the Finney pyloroplasty.

5. The use of pyloroplasty or pyloromyotomy to facilitate gastric emptying following transection of the cardia for oesophagectomy is controversial. Some surgeons perform it only if there is evidence of stenosis (see Chapter 9). In the event of delayed gastric emptying they give metoclopramide 5–10 mg intravenously, and balloon dilatation of the pylorus under radiological control; they reserve re-operation for patients in whom these methods fail. The experience of other surgeons gives less cause for optimism so they routinely perform pyloroplasty or pyloromyotomy to circumvent gastric delay.

HEINEKE-MIKULICZ PYLOROPLASTY

Action

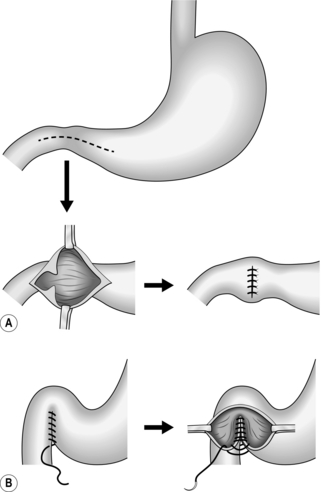

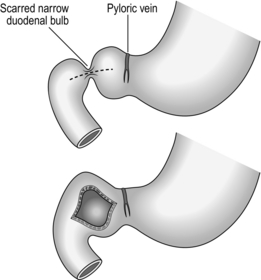

1. Make a longitudinal incision through all coats starting on the anterior wall of the duodenal bulb, carried through the pylorus and on to the anterior gastric antral wall (Fig. 10.14). Centre the incision, 4–5 cm long, on the narrowest part of the pyloroduodenal canal. If there is an active anterior ulcer, encircle it so that a lozenge-shaped segment of anterior pyloroduodenal wall is excised, containing the ulcer. This ‘pylorectomy’ was described by Judd.

2. Aspirate the contents and inspect the interior of the distal stomach and proximal duodenum. Sometimes there is a mucosal diaphragm with no evidence of ulcer in patients with typical features of pyloric stenosis in whom an endoscope would not pass. If a diaphragm is suspected, start the incision on the anterior antral wall 3–4 cm proximal to the pylorus and inspect the interior before cutting through the pyloric ring. Make sure there is not a second narrow duodenal segment distal to the pyloroplasty, as may develop in postbulbar duodenal ulceration.

3. Gently apply tissue forceps to the middle of the upper and lower cut edges and draw them apart, allowing the proximal and distal limits of the incision to come together, transforming the longitudinal cut into a transverse slit.

4. Close the incision, starting from the upper tissue forceps and ending at the lower forceps. Three methods are possible. The traditional technique is to insert an invaginating continuous all-coats layer reinforced with a second seromuscular layer of sutures. However, the invaginated edges may cause a temporary holdup and many surgeons therefore employ a single layer of all-coats sutures placed closely together, uniting the walls edge-to-edge without invagination. In the last few years stapling devices have gained popularity. Place a single straight stapler along the edges as they are held in their new position, with the opposed edges everted. Close and activate the stapler. Cut off the excess tissue with a scalpel blade held in contact with the upper surface of the stapler, which is then removed. Insert a reinforcing layer of seromuscular stitches if desired.

FINNEY PYLOROPLASTY

Action

1. Gently mobilize the duodenal loop by Kocher’s manoeuvre so the descending duodenum can be laid alongside the greater curve part of the gastric antrum.

2. Unite the adjacent gastric and duodenal walls with a seromuscular stitch, from above downwards, closing the angle below the pylorus.

3. Incise the full thickness of the stomach, pylorus and duodenum along an inverted horseshoe-shaped line which runs from the gastric antrum 4–5 cm proximal to the pyloric ring, through the pylorus, curving through the duodenal bulb and down the descending duodenum.

4. Starting at the pylorus, unite with an all-coats stitch the adjacent walls of the stomach and duodenum. Continue the stitches round the lower limits of the incisions to unite the right duodenal cut edge to the left gastric cut edge, using an invaginating stitch.

5. Continue the seromuscular stitch to cover the anterior all-coats suture line.

DUODENOPLASTY

Appraise

1. The advent of proximal gastric vagotomy removed the need to perform an adjunctive drainage operation in the majority of patients with duodenal ulcer since in modern times most patients with incipient pyloric stenosis are operated upon before it becomes severe.

2. Even if pyloroplasty is necessary there are advantages in performing proximal gastric vagotomy. If truncal vagotomy is performed, gallbladder dilatation results and there is an increased risk of gallstones; loss of vagal supply to the pancreas reduces its exocrine secretion and there is a significantly increased risk of severe diarrhoea. In some patients, stenosis is distal to the pylorus and can be overcome without damaging the sphincteric mechanism. This is particularly true when the patient has postbulbar duodenal ulceration. Proximal gastric vagotomy can then be justified.

Action

1. Mobilize the pyloroduodenal region by Kocher’s manoeuvre and confirm that the pyloric ring itself is widely patent by invaginating the anterior antral wall through it on an index finger. The site of stenosis should have been determined before operation but this is not always easy to assess.

2. Make a longitudinal incision through the anterior duodenal wall, stopping short of the pyloric ring (Fig. 10.15). This needs to be only about 1.5–2 cm long. If the ulcer and stenosis are postbulbar remember that the distortion may draw the ampulla out of its normal place, exposing it to inadvertent damage.

Fig. 10.15 Duodenoplasty.

3. Gently apply tissue forceps to the middle of each cut edge and separate them to produce a transverse slit.

4. Close the slit transversely. Insert a single layer of closely applied stitches, bringing the edges together without inversion.

GASTRODUODENOSTOMY

Action

1. Mobilize the descending duodenum by Kocher’s manoeuvre and join the descending duodenum to the anterior wall of the distal stomach with a running seromuscular stitch.