Chapter 27 Stent Insertion for Tracheo-Broncho-Esophageal Fistula at the Level of Lower Trachea and Left Mainstem Bronchus

Case Description

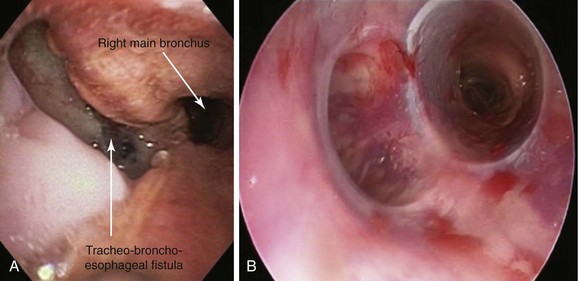

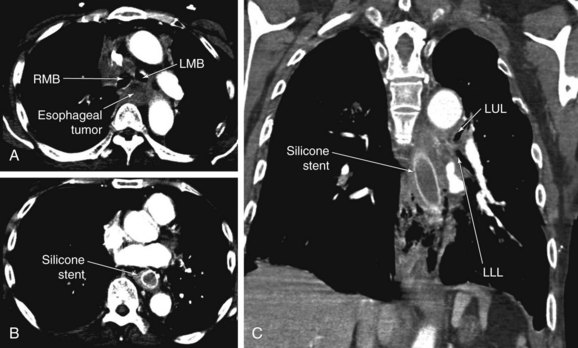

A 74-year-old male with a 25–pack-year smoking history developed hoarseness and dysphagia to solid and semisolid foods. Symptoms progressed to intractable cough and pneumonia. He had a 40 pound weight loss over the last few months before admission to the hospital. Flexible bronchoscopy showed an immobile left vocal cord and a mass penetrating the posterior wall of the left main bronchus (LMB). Biopsy revealed squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Initially, the patient declined treatment, but when he became unable to swallow at all and developed a severe productive cough, a percutaneous gastrostomy tube was placed. Flexible bronchoscopy this time showed a large tracheo-broncho-esophageal fistula, prompting transfer to our institution for further care. Vital signs revealed HR of 115/min, RR of 23/min, temperature of 100° F, and blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg. Coarse rhonchi were heard bilaterally, as was a focal wheeze on the left during forced exhalation, accompanied by decreased breath sounds at the base of the left lung. Laboratory markers were significant for albumin 1.6, WBC 14, and hemoglobin 11. Chest radiograph showed patchy bilateral infiltrates, dense left lower lobe opacification, and a left suprahilar mass. A repeat flexible bronchoscopy at our institution revealed a 3 cm fistula at the junction of the posterior and lateral walls of the LMB, extending proximally to the lower trachea (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.27.1![]() ). Associated compression of the LMB and a distorted main carina were noted. A silicone Y stent was placed at the main carina via rigid bronchoscopy (Figure 27-1).

). Associated compression of the LMB and a distorted main carina were noted. A silicone Y stent was placed at the main carina via rigid bronchoscopy (Figure 27-1).

Case Resolution

Initial Evaluations

Physical Examination, Complementary Tests, and Functional Status Assessment

Most adults with esophago-respiratory fistulas (ERFs) have the acquired form of disease comprising tracheo-esophageal, broncho-esophageal, or tracheo-broncho-esophageal fistulas. Their prognosis and management depend on whether the fistula is the result of a benign process or a malignancy, with the latter usually due to primary esophageal cancer. In one series of 264 patients with malignant ERF, 243 (92%) had esophageal cancer, 19 (7%) had lung cancer, and 2 (1%) had mediastinal tumor.1 Results from studies show an overall frequency of ERF in patients with esophageal cancer of 5% to 10%, but fistulas may be more common toward the terminal stage of the disease.1 Compared with patients without ERF, those with esophageal cancer and ERF present at a more advanced stage of disease, have more frequent involvement of the upper to mid-thoracic esophagus, and have a longer segment of tumor. Although the median time from diagnosis of esophageal cancer to the development of a fistula is approximately 8 months, our patient was diagnosed with ERF only 2 months after his initial diagnosis. ERF can be the presenting manifestation of cancer in approximately 6% of cases.1 The median survival time after diagnosis of ERF is only 8 weeks.2

During initial evaluation of these patients, a thorough oncologic treatment history is important because the use of some antiangiogenesis drugs such as bevacizumab, along with radiation therapy, has been linked to the development of malignant ERF.3 Nonmalignant causes of ERF include complications of mechanical ventilation or indwelling tracheal or esophageal stents, complications from prior tracheal or esophageal surgery, granulomatous mediastinal infection (tuberculosis, syphilis, histoplasmosis), trauma (blunt or penetrating), and ingestion of caustic or foreign bodies. A large study from the Mayo Clinic found that esophageal surgery was the most common cause of nonmalignant ERF.4

Regardless of its origin, ERF is a life-threatening condition with severe pulmonary complications consisting of ongoing tracheobronchial bacterial contamination and impaired nutrition.4 Patients present with intractable cough, recurrent respiratory infections, rapid deterioration, and death, if left untreated.2,5,6 In a study of 207 malignant trachea-esophageal fistulas (TEFs), symptoms and signs included cough in 116 (56%), aspiration in 77 (37%), fever in 52 (25%), dysphagia in 39 (19%), pneumonia in 11 (5%), hemoptysis in 10 (5%), and chest pain in 10 (5%).7 Our patient’s aspiration probably was worsened by his left recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, causing an immobile left vocal cord (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.27.2![]() ). Seen in approximately 10% of patients with ERF, this finding contributes to swallowing difficulties and periodic or constant aspiration.1

). Seen in approximately 10% of patients with ERF, this finding contributes to swallowing difficulties and periodic or constant aspiration.1

Comorbidities

This patient had pneumonia, was hospitalized, and had a poor performance status (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG]/Zubrod 4).* His pneumonia resulted in sepsis, but no evidence was found of other organ dysfunction that could have interfered with anesthesia and perioperative care. He was severely malnourished, as manifested by his anemia and hypoproteinemia. Wound healing, in particular healing of the anastomosis in case surgery is performed, would be expected to be poor. Muscle wasting reduces respiratory reserve and the patient’s ability to breathe, cough, and clear secretions.8

Support System

This gentleman had a supportive wife. Married patients have been shown to have a lower risk of death than unmarried patients, independent of socioeconomic status.9 In addition, relevant to this case, married patients suffering from esophageal carcinoma report higher baseline quality of life with regard to legal concerns (e.g., having a will, advance directives) and friend and family support compared with single patients. Over time, married patients may have a decrease in pain frequency compared with single patients.10

Patient Preferences and Expectations

Our patient showed understanding of the gravity of his diagnosis. Patients with ERF have a poor prognosis, and many patients die from respiratory infection and malnutrition within a month of diagnosis.11 Control of pulmonary contamination provides an opportunity for secondary treatment, as well as for improved survival and quality of life. Therefore treatment should include closure of the fistula and re-establishment of oral intake in a timely and cost-efficient manner, while minimizing the need for secondary medical interventions. Our patient wished he could eat and breathe better during the time he had left to live, but he did not want to be a burden to his wife. A significant proportion of caregivers of patients with esophageal cancer experience high levels of strain and psychological distress. Support and services targeted specifically at reducing the considerable strain of caring for patients with esophageal cancer are necessary, particularly for caregivers of patients from lower socioeconomic groups.12

Procedural Strategies

Indications

Treatment must correct the two problems of airway contamination and poor nutrition. Reflux of gastric contents is diminished by placement of a gastrostomy tube, and adequate nutrition is sometimes facilitated by insertion of a jejunostomy tube. Treatment depends on whether the patient is resectable and medically fit for surgical therapy. Like our patient, most patients have advanced disease and can be treated only with palliative measures, which involve restoration of the swallowing mechanism and prevention of aspiration. The current standard of palliative therapy for patients with malignant ERF is endoscopic or radiologic placement of esophageal-covered self-expanding metallic stents (SEMS), allowing closure of the fistula. Less common treatment options for selected patients with malignant ERF include chemotherapy and radiation, surgical bypass, esophageal exclusion, and fistula resection and repair.13 Our patient’s functional status and concurrent aspiration pneumonia precluded surgical treatment, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy. We chose to proceed first with silicone airway stent insertion with the goal of palliating left main bronchial patency and covering the fistula, followed by esophageal stent insertion to help prevent aspiration and facilitate oral food intake.

Contraindications

No absolute contraindications to stent insertion or general anesthesia were noted. Given the patient’s age and extensive smoking history, a cardiology evaluation was requested before intervention. He was considered to be at intermediate risk (1% to 5%) for cardiac death or nonfatal myocardial infarction. Blood gas analysis showed a partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) of 55 mm Hg and an arterial carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2) of 60 mm Hg on room air. The risk associated with this degree of PaCO2 elevation is not prohibitive for a necessary intervention, although it should lead to reassessment of the indication for the proposed procedure and aggressive preoperative preparation. Although preoperative hypoxemia and postoperative pulmonary complications may be associated in patients undergoing surgery,14 hypoxemia generally has not been identified as a significant independent predictor of complications after adjustment for potential confounders.

Expected Results

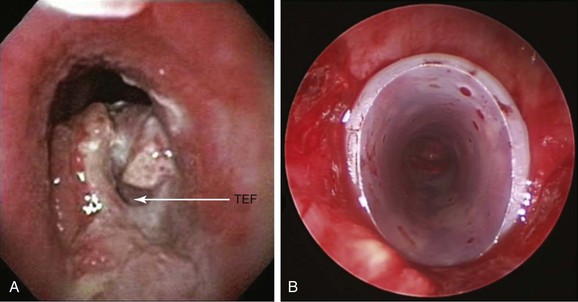

Palliation for malignant ERF is usually achieved with endoscopic placement of esophageal, airway, or parallel (dual) stent insertion (in the esophagus and airway). Dual stent insertion appears to work better than a single prosthesis. Particular attention should be paid to airway compression or erosion caused by esophageal stents, prompting some authorities to initially place an airway stent before placing the esophageal one, especially if significant tracheobronchial obstruction is a matter of concern (Figure 27-2). Results from small case series show that respiratory distress can occur from severe airway obstruction caused by extrinsic compression after esophageal stent insertion.15 Silicone or covered metallic stents may be preferred for the airway to prevent recurrence of airway narrowing by growth of tumor between the wires of metal stents. For instance, one study evaluated the clinical benefits and complications of studded silicone stent insertion in 35 patients, of whom 6 had ERF. Three of 6 patients showed resolution of the fistula, and 3 other patients improved symptomatically.16 Symptoms of ERF usually improve after double stent insertion. ERF symptoms may recur as the result of stent-induced pressure necrosis of tracheal and esophageal walls. In addition to fistula enlargement, other complications described with stents placed in the esophagus, in the airway, or after dual stent insertion include pain, reflux, stent migration or fracture, restenosis, massive bleeding, aspiration, airway obstruction, tumor overgrowth, and food impaction.1,17

Team Experience

A multidisciplinary approach involving the gastroenterologist, the interventional pulmonologist, the oncologist, and the thoracic surgeon may be helpful. Patients with ERF are prone to develop worsening wall perforation and erosion because of the nature of malignant infiltration, stent-induced necrosis, or concurrent or previously applied radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Locations, the number of stents, and their type and size should be discussed.18 Some prefer to insert an esophageal stent, an airway stent, and a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube at the same time, during a single session with the patient under general anesthesia.19 Others perform procedures sequentially. Interventions performed by different services need to be coordinated, so good communication among treating teams is necessary.

Therapeutic Alternatives

Treatment is individualized and may include esophageal stenting, tracheobronchial stenting, simultaneous stenting of the trachea and esophagus, esophageal exclusion, esophageal bypass, fistula resection, and repair and radiation therapy.18 Direct surgical fistula closure or resection does not yield satisfactory results in this population. In general, surgical esophageal bypass can resolve respiratory contamination and allow fairly normal swallowing, but it should be reserved for patients who can tolerate a major operation. Esophageal stent insertion helps prevent aspiration and allows swallowing. This procedure can be offered to nearly all patients, regardless of their physiologic condition. The most effective reported treatments are esophageal bypass and esophageal stent insertion. When performed promptly after diagnosis, these treatments may improve survival and quality of life.13 Discussion of available treatment modalities is warranted among treating team members, and specific indications, contraindications, advantages, and disadvantages of each should be shared with patients and their families.

1. Surgical treatment: Surgical procedures carry high morbidity and mortality with relatively poor results.7 Possible treatments for malignant ERF include resection of the esophagus, collar esophagostomy with gastrostomy or jejunostomy for nutrition, and esophageal bypass.1 Given the patient’s short life expectancy and poor state of health, reconstructive surgical interventions usually are not considered. Studies from centers with access to experienced thoracic and esophageal surgeons have shown that in selected patients, palliation and prolonged survival are obtained with surgical bypass, the hallmark of which is leaving the ERF in place while diverting oral intake retrosternally with the stomach or the colon. In 21 patients with malignant ERF, gastric bypass with lower esophageal exclusion (aka Kirschner operation)* provided a beneficial palliative effect despite a high risk of operative mortality. An overall 30 day mortality of 38% prompted authors to recommend this procedure for patients who do not tolerate stents or in whom stent deployment was unsuccessful, as well as for patients who are in good general health and without respiratory complications that might compromise surgery.20 Median survival of 55 days, median length of stay in the ICU of 6 days, and hospitalization duration of 17 days raise concerns regarding the quality of life of these terminally ill patients. Furthermore, the very high mortality rate might be considered unacceptable from a health care economics perspective. In another case series of 207 patients with malignant ERF, the percentage of patients alive at 3, 6, and 12 months was 13%, 4%, and 1% in case of supportive care (n = 104); 17%, 3%, and 0%, respectively, for esophageal exclusion (n = 29); 21%, 14%, and 0% for esophageal prosthesis (n = 14); 30%, 15%, and 5% for radiation therapy (n = 20); and 46%, 20%, and 7% for esophageal bypass. Patients treated with radiation therapy and esophageal bypass had prolonged survival compared with patients treated by other means.7 Based on these data, it seems that esophageal bypass probably offers the best palliation for operable patients.* In general, surgical bypass is reserved for patients with a very large fistula and for those in whom permanent stent placement is unsuccessful or inadvisable, provided patients are in good physical condition, and that general anesthesia and orotracheal intubation are technically feasible.21

2. DJ fistula stent: This cufflink-shaped prosthesis (Bryan Corp., Woburn, Mass) is designed exclusively for closure of malignant ERF secondary to esophageal or lung cancer. It can be sized to the fistula diameter to occlude the abnormal communication.18 The stent consists of a top portion, which seals the tracheal defect; a vertical axis, which blocks the passage between the trachea and the esophagus; and a lower ellipse-shaped portion, which anchors the stent in position in the esophageal lumen.22

3. Esophageal stent insertion: A covered expandable esophageal stent (SEMS) can relieve symptoms in more than 80% of patients with malignant ERF.18,23 Placement of an SEMS is emerging as a superior alternative to the use of nonexpandable esophageal prostheses and other treatment methods such as percutaneous gastrostomy or surgical esophageal bypass, in terms of successful treatment of malignant dysphagia and associated complications.24 Fistula occlusion was shown to be more successful with SEMS (92%) than with conventional nonexpanding stents (77%). Reintervention was required more commonly with SEMS21 but without the frequency of complications such as perforation, hemorrhage, pressure necrosis, obstruction, dislodgment, and migration, which occur in approximately 15% to 40% of patients with nonexpandable esophageal prostheses.25 Successful closure of ERF by esophageal stent placement improved survival and quality of life in a case series of 264 patients; procedure-related mortality was 0.5%. Mean survival for all patients was 2.8 months, but it was 3.4 months in patients with an implanted endoprosthesis† and less than 2 months in those with only supportive therapy.1 Stents with barbed covered metallic anchors to the mucosa were used successfully to prevent stent migration in a case series of 20 patients.26 Esophageal stents can be inserted with the patient under general anesthesia via rigid esophagoscopy, or via flexible esophagoscopy with moderate sedation.27,28

4. Dual stent insertion (esophagus and airways): This approach has been proposed when fistula occlusion is not achieved by the esophageal or airway prosthesis alone.29–31 This technique has yielded better results than stents in the airway or the esophagus alone. In such cases, as with our patient, the airway stent should be placed before the esophageal one to prevent airway compression secondary to the esophageal prosthesis.17,24,32 Some experts consider early double stent insertion when the location, volume, and extent of esophageal and respiratory disease predispose to erosion and further rupture of the airway or esophageal wall.23,30,33

5. Supportive care: This consists of operative gastrostomy, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, parenteral nutrition, intravenous rehydration, and antibiotic and analgesic therapy. In one of the largest series reviewing the outcomes of 207 patients with malignant ERF, patients who received supportive care alone survived a median of only 22 days.7

Cost-Effectiveness

One comparative study evaluated the survival time and quality of life of patients who received different treatments for malignant ERF.17 Thirty-five patients diagnosed with malignant ERF secondary to esophageal cancer were nonrandomly divided into three groups: (1) 17 patients who received esophageal self-expandable Nitinol stents, (2) 9 patients who received laparoscopic gastrostomy, and (3) a control group of 9 patients who refused both stent insertion and gastrostomy. Authors found no statistically significant difference in survival time, but palliation of respiratory symptoms was best achieved in the stent group versus the gastrostomy group or controls. Patients in the stent group had better quality of life as graded by a quality-of-life questionnaire, particularly with regard to dyspnea, dysphagia, eating problems, dry mouth, cough, and hypersalivation. Dual stent insertion (esophagus and airways) is widely accepted when fistula occlusion is not achieved by esophageal or airway stent alone.30,31,33

Techniques and Results

Anesthesia and Perioperative Care

Several anesthesia-related problems are seen in patients with ERF. If face mask ventilation is not possible, spontaneous ventilation should be maintained until the rigid bronchoscope has been positioned successfully. We prefer employing spontaneous ventilation, but this may be difficult because the stimulation produced by the rigid bronchoscope is sometimes such that it is difficult to have a spontaneously breathing patient sufficiently anesthetized to tolerate the bronchoscope. Although the rigid bronchoscope has a port for ventilation, establishment of controlled ventilation is expected to be somewhat compromised because oxygen delivered through the bronchoscope can be diverted through the large fistula to the esophagus, instead of to the lungs.34 Theoretically, this could also increase the size of the fistula and decrease tidal volume, resulting in an inability to ventilate the lungs effectively. Massive loss of tidal volume is uncommon in clinical practice, but the patient’s spontaneous ventilation probably should not be abolished until it has been demonstrated that it is possible to inflate the lungs by gentle manual ventilation.8 The amount of gas lost through the fistula depends on airway pressure and lung compliance, in addition to the size of the defect. The lung on the side of the fistula is likely to be contaminated and therefore less compliant than the contralateral lung; thus the contralateral lung tends to be ventilated preferentially. If the patient does not already have an esophageal stent, the expected difficulty of ventilation can be solved by partially sealing the fistula from the esophageal side with an esophageal balloon. In this regard, use of high-frequency jet ventilation might be considered because it offers the theoretical advantage of potentially reducing gas loss through the fistula.

The presence of the fistula presents two additional problems: First, vigorous manual ventilation should be avoided before intubation because this tends to force gas through the fistula and may produce intestinal distention. When severe, this can lead to gastric rupture, hypotension, and cardiac arrest.8 The marked increase in intra-abdominal and intrathoracic pressures may affect venous return, producing cardiovascular depression. Second, most patients with ERF suffer from pulmonary aspiration of esophago-gastric contents. It is possible that further contamination of the less affected lung may occur before isolation of the fistula. Gentle ventilation with avoidance of gastric distention should minimize this risk. Frequent bronchial hygiene may be necessary to remove secretions during and after anesthesia.

Instrumentation

We had available a variety of large-channel ventilating bronchoscopes but planned on intubating the patient with a 13 mm Efer-Dumon bronchoscope (Bryan Corp.) to allow deployment of a large silicone Y stent (16 mm × 13 mm × 13 mm) at the level of the main carina. These stents were shown to reduce dyspnea and recurrent infection in patients with airway fistulas.35

Anatomic Dangers and Other Risks

Enlargement of the fistula is possible during airway stent insertion and manipulation. Inadvertent mediastinal insertion or migration of airway stents has been reported (Figure 27-3).36 Other risks associated with dual stent insertion include massive bleeding, uncontrollable esophago-airway fistula, mediastinitis, pneumothorax, and vascular fistulas.37,38

Results and Procedure-Related Complications

With the patient under general anesthesia with spontaneous-assisted ventilation, a 13 mm Efer-Dumon ventilating bronchoscope was inserted without difficulty into the patient’s trachea. Bronchial hygiene was performed using the flexible scope. The fistula was seen in the lower trachea and the proximal left main bronchus (LMB), extending for 3 cm at the junction between the posterior and lateral walls of the LMB. The esophagus could be seen herniating into and obstructing the LMB (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.27.1![]() ). The Y stent was tailored to extend 5 cm into the LMB and 1 cm into the right main bronchus (RMB) because the orifice of the right upper lobe (RUL) was only 1 cm below the carina. Y stents are usually deployed using a pullback or a push technique. When the pullback technique is used, the stent can be deployed in its entirety into the ipsilateral bronchus using the stent pusher or even the rigid telescope. The tracheal limb then is grasped with forceps and pulled back gently until the contralateral limb of the stent deploys into the contralateral bronchus (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.27.3

). The Y stent was tailored to extend 5 cm into the LMB and 1 cm into the right main bronchus (RMB) because the orifice of the right upper lobe (RUL) was only 1 cm below the carina. Y stents are usually deployed using a pullback or a push technique. When the pullback technique is used, the stent can be deployed in its entirety into the ipsilateral bronchus using the stent pusher or even the rigid telescope. The tracheal limb then is grasped with forceps and pulled back gently until the contralateral limb of the stent deploys into the contralateral bronchus (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.27.3![]() ).

).

In our patient, a Y stent could not be loaded because the specially designed introducer system had been lost that morning in sterile processing. Instead, the rigid bronchoscope was removed, and a Rusch forceps was used to promptly insert the stent via direct laryngoscopy (Figure 27-4). Once the stent was inside the airway, the patient was reintubated with an 11 mm Efer-Dumon rigid bronchoscope, and forceps was used to ensure that the stent was securely in position, and that the fistula was entirely covered (see Figure 27-1). The patient was extubated uneventfully and was transferred to the ICU for monitoring.

Long–Term Management

Follow-up Tests and Procedures

After stent placement, bronchoscopy can be performed to evaluate occlusion of the fistula by the stent. If the stent completely seals the fistula, the patient is allowed a soft diet 2 hours after the procedure and is encouraged to resume a tolerable diet as soon as possible. Esophagography can be performed within 7 days after stent placement and every 1 to 2 months thereafter to evaluate ERF occlusion and stent position.39

Three days after esophageal stent placement, however, our patient developed massive hemoptysis and acute respiratory failure requiring emergent intubation with a No. 6 cuffless endotracheal tube. Emergent bronchoscopy showed a large amount of blood flowing from the left main bronchus and spilling into the trachea and right bronchial tree (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video VI.27.4![]() ). The patient was immediately turned toward the left lateral decubitus position, and continuous suction of bright red blood was performed while we actively commenced resuscitation. The bleeding was emerging from the distal left main bronchus, but the exact location could not be visualized bronchoscopically. Given the nature of the massive active hemorrhage, a broncho-vascular fistula was the likely cause. The bleeding was stopped by insertion of an endobronchial blocker; the patient regained consciousness, and the next day he was extubated, but because he was not a candidate for surgical interventions, supportive care was provided. Two days later, massive hemoptysis recurred and the patient expired. Autopsy was offered but was declined by his wife.

). The patient was immediately turned toward the left lateral decubitus position, and continuous suction of bright red blood was performed while we actively commenced resuscitation. The bleeding was emerging from the distal left main bronchus, but the exact location could not be visualized bronchoscopically. Given the nature of the massive active hemorrhage, a broncho-vascular fistula was the likely cause. The bleeding was stopped by insertion of an endobronchial blocker; the patient regained consciousness, and the next day he was extubated, but because he was not a candidate for surgical interventions, supportive care was provided. Two days later, massive hemoptysis recurred and the patient expired. Autopsy was offered but was declined by his wife.

Quality Improvement

We did not use existing validated tools to assess this patient’s quality of life. One such instrument (QLQ-OG25), designed for patients with esophageal cancer, has six scales pertaining to dysphagia, eating restrictions, reflux, odynophagia, pain, and anxiety. These scales have good reliability and are able to distinguish quality of life differences among different tumor sites and disease stages.40 Given our patient’s dismal prognosis, we probably should have involved palliative care and hospice services earlier during his hospitalization. Although our goal was to eliminate dysphagia and improve quality of life, it is possible that in view of his very poor general health status, an indwelling percutaneous feeding tube and general palliative measures should have been offered instead of endoscopic and bronchoscopic interventions. Continuity of health and life might have been enhanced through a hospice home care program and appropriate comfort measures to alleviate terminal symptoms that would have allowed our patient to die with dignity and without suffering the effects of cardiopulmonary resuscitation.41

Discussion Points

1. What is the expected survival in this patient with and without treatment of the malignant esophago-respiratory fistula?

2. List three therapeutic alternatives for occluding an esophago-respiratory fistula.

3. List three expected benefits dervived from stent insertion in this patient.

Expert Commentary

Types and Cause of Fistulas

Aerodigestive fistulas can be connatal, when the septum between the trachea and the esophagus is incomplete or perforated. The most frequent type is the so-called Vogt IIIb,* in which a small duct connects the trachea to the esophagus, frequently in a downward direction. The fistula is diagnosed most often in early childhood by accidental aspiration. Frequently, the fistula can be closed by endoscopic means such as electrocautery and/or sealing by glue. In rare instances, the fistula never causes problems and is found by chance in adulthood. Other types of fistulas are post-traumatic. These can result from difficult intubation or from interventional bronchoscopic procedures. Especially in post intubation trauma, the diagnosis is missed easily if the endotracheal tube cuff obstructs the lesion. Often, it is only the dislocation of the cuff or extubation that unmasks the defect, resulting in mediastinal emphysema and aspiration. Early diagnosis of this complication and its surgical repair by primary closure of the esophageal and tracheal leak are mandatory, in which case complications are infrequent. Delayed surgical intervention, however, may be accompanied by delayed postoperative healing due to infection. A third type of fistula is postsurgical, occurring most often after esophageal segmental resection. These usually occur at the site of anastomosis, especially in cases of complicated wound healing after preoperative chemo-radiotherapy. They are very difficult to surgically repair, even when bypass and transplant procedures, vascularized muscle flaps, or other techniques are used.

* Congenital esophageal atresia (EA) and trachea-esophageal fistula (TEF) may exist as separate entities, but most people have both, and therefore the classification systems group them together. Five types of congenital EA/TEF and two classification systems—Gross and Vogt classification systems—have been identified. Gross type C (Vogt type IIIb) EA/TEF, which consists of distal TEF with proximal EA, is the most common type (88.5%). Gross type A (Vogt type II) is isolated EA, and Gross type E (TEF without EA or H-type TEF) is less common (8% and 4%, respectively); the remainder consist of Gross types B (Vogt III a) (proximal TEF with distal EA) and D (Vogt IIIc) (proximal TEF and distal TEF) (Chest. 2004;126:915-925).

1. Balazs A, Kupcsulik PK, Galambos Z. Esophagorespiratory fistulas of timorous origin: nonoperative management of 264 cases in a 20-year period. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:1103-1107.

2. Choi MK, Park YH, Hong JY, et al. Clinical implications of esophagorespiratory fistulae in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (SCCA). Med Oncol. 2010;27:1234-1238.

3. Spigel DR, Hainsworth JD, Yardley DA, et al. Tracheoesophageal fistula formation in patients with lung cancer treated with chemoradiation and bevacizumab. J Clin Oncol. 2009;28:43-48.

4. Shen KR, Allen MS, Cassivi SD, et al. Surgical management of acquired nonmalignant tracheoesophageal and bronchoesophageal fistulae. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:914-919.

5. Lee KE, Shin JH, Song HY, et al. Management of airway involvement of oesophageal cancer using covered retrievable Nitinol stents. Clin Radiol. 2009;64:133-141.

6. Kim KR, Shin JH, Song HY, et al. Palliative treatment of malignant esophagopulmonary fistulas with covered expandable metallic stents. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:W278-W282.

7. Burt M, Diehl W, Martini N, et al. Malignant esophagorespiratory fistula: management options and survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 1991;52:1222-1229.

8. Grebenik CR. Anaesthetic management of malignant tracheo-oesophageal fistula. Br J Anaesth. 1989;63:492-496.

9. Jaffe DH, Manor O, Eisenbach Z, et al. The protective effect of marriage on mortality in a dynamic society. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:540-547.

10. Miller RC, Atherton PJ, Kabat BF, et al. Marital status and quality of life in patients with esophageal cancer or Barrett’s esophagus: the Mayo Clinic Esophageal Adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s Esophagus Registry study. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2860-2868.

11. Chung SC, Stuart RC, Li AK. Surgical therapy for squamous-cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. Lancet. 1994;343:521-524.

12. Donnelly M, Anderson LA, Johnston BT, et al. Oesophageal cancer: caregiver mental health and strain. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17:1196-1201.

13. Reed MF, Mathisen DJ. Tracheoesophageal fistula. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 2003;13:271-289.

14. Fan ST, Lau WY, Yip WC, et al. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications in oesophagogastric cancer surgery. Br J Surg. 1987;74:408-410.

15. Nomori H, Horio H, Imazu Y, et al. Double stenting for esophageal and tracheobronchial stenoses. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1803-1807.

16. Mitsuoka M, Sakuragi T, Itoh T. Clinical benefits and complications of Dumon stent insertion for the treatment of severe central airway stenosis or airway fistula. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;55:275-280.

17. Hu Y, Zhao Y-F, Chen L-Q, et al. Comparative study of different treatments for malignant tracheoesophageal/bronchoesophageal fistulae. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:526-531.

18. Rodriguez AN, Diaz-Jimenez JP. Malignant respiratory-digestive fistulas. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16:329-333.

19. Freitag L. Airway stents. In: Strausz J, Bolliger CT. Interventional Pulmonology. Lausanne, Switzerland: European Respiratory Society; 2010:190-217.

20. Meunier B, Stasik C, Raoul JL, et al. Gastric bypass for malignant esophagotracheal fistula: a series of 21 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;13:184-188.

21. Low DE, Kozarek RA. Comparison of conventional and wire mesh expandable prostheses and surgical bypass in patients with malignant esophagorespiratory fistulas. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:919-923.

22. Diaz-Jimenez P. New cufflink-shaped silicone prosthesis for the palliation of malignant tracheobronchial-esophageal fistula. J Bronchol. 2005;12:207-209.

23. Shin JH, Song HY, Ko GY, et al. Esophagorespiratory fistula: long-term results of palliative treatment with covered expandable metallic stents in 61 patients. Radiology. 2004;232:252-259.

24. Sharma P, Kozarek R, The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Role of esophageal stents in benign and malignant diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:258-273.

25. Weigert N, Neuhaus H, Rosch T, et al. Treatment of esophagorespiratory fistulas with silicone-coated self-expanding metal stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:490-496.

26. Kim YH, Shin JH, Song HY, et al. Treatment of tracheal strictures or fistulas using a barbed silicone-covered retrievable expandable Nitinol stent. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:W232-W237.

27. Turkyilmaz A, Aydin Y, Eroglu A, et al. Palliative management of esophagorespiratory fistula in esophageal malignancy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:364-367.

28. Ross WA, Alkassab F, Lynch PM, et al. Evolving role of self-expanding metal stents in the treatment of malignant dysphagia and fistulas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:70-76.

29. Colt HG, Meric B, Dumon JF. Double stents for carcinoma of the esophagus invading the tracheo-bronchial tree. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:485-489.

30. Albes JM, Schafers HJ, Gebel M, et al. Tracheal stenting for malignant tracheoesophageal fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57:1263-1266.

31. Freitag L, Tekolf E, Steveling H, et al. Management of malignant esophagotracheal fistulas with airway stenting and double stenting. Chest. 1996;110:1155-1160.

32. Nomori H, Horio H, Imazu Y, et al. Double stenting for esophageal and tracheobronchial stenoses. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:1803-1807.

33. van den Bongard HJ, Boot H, Baas P, et al. The role of parallel stent insertion in patients with esophagorespiratory fistulas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:110-115.

34. Inada T, Umemoto M, Ohshima T, et al. Anesthesia for insertion of a Dumon stent in a patient with a large tracheo-esophageal fistula. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46:372-375.

35. Dutau H, Toutblanc B, Lamb C, et al. Use of the Dumon Y-stent in the management of malignant disease involving the carina: a retrospective review of 86 patients. Chest. 2004;126:951-958.

36. Alazemi S, Chatterji S, Ernst A, et al. Mediastinal migration of self-expanding bronchial stents in the management of malignant bronchoesophageal fistula. Chest. 2009;135:1353-1355.

37. Tomaselli F, Maier A, Sankin O, et al. Successful endoscopical sealing of malignant esophageotracheal fistulae by using a covered self-expandable stenting system. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20:734-738.

38. Yamamoto R, Tada H, Kishi A, et al. Double stent for malignant combined esophago-airway lesions. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;50:1-5.

39. Kim JH, Shin JH, Song HY, et al. Esophagorespiratory fistula without stricture: palliative treatment with a barbed covered metallic stent in the central airway. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:84-88.

40. Lagergren P, Fayers P, Conroy T, et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-OG25, to assess health-related quality of life in patients with cancer of the oesophagus, the oesophago-gastric junction and the stomach. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:2066-2073.

41. Sharma S, Walsh D. Symptom management in esophageal cancer. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1994;4:369-383.

* Completely disabled; cannot carry out any self-care; totally confined to bed or chair.

* The Kirschner operation was carried out in all patients with retrosternal tubulization of the stomach and exclusion of the lower end of the esophagus using a Roux-en-Y loop or ligature. This procedure could be proposed to patients with fistula located in the thoracic esophagus, even in the upper third. Obviously, patients with fistula involving the cervical esophagus could not benefit from this technique.

* This management is different than management for nonmalignant TEFs, for which several differing approaches have been proposed but the optimal management strategy remains controversial. Direct suture closure of both tracheal and esophageal defects, segmental tracheal resection and primary anastomosis with direct esophageal closure, tracheal closure using an esophageal patch, closure of the defects with soft tissue flaps, a combined surgical and endoscopic approach, and a two-stage approach with esophageal diversion and primary closure of the tracheal defect have all been advocated. In one of the largest published series, 35 patients underwent surgical repair of acquired nonmalignant fistula between the airway and the esophagus. In this population, single-stage primary repair of airway and esophageal defects with tissue flap interposition was performed successfully in most patients, with an overall surgical mortality of 5.7%.4

† Stents used were covered and included mainly a steel wire–armored Haring endoprosthesis (Rusch), Wilson-Cook tubes (Wilson-Cook Medical), and Ultraflex self-expanding stents (Boston Scientific).