Chapter 61 Status Epilepticus

3 Describe the classification and clinical presentation of SE

Generalized convulsive SE involves tonic flexion of the axial muscles, flexion in the arms and legs followed by extension, clenching of teeth, forced expiration, dilation of the pupils or sluggish pupillary light responses, and upward or lateral eye deviation. The uninterrupted jerking or shivering during the clonic phase may gradually resolve, but tonic spasm may occur again with a similar pattern of jerking and resolution. As the duration of the seizures increases, the movements and muscle contractions may become reduced despite continued generalized electrical activity in the brain.

Generalized convulsive SE involves tonic flexion of the axial muscles, flexion in the arms and legs followed by extension, clenching of teeth, forced expiration, dilation of the pupils or sluggish pupillary light responses, and upward or lateral eye deviation. The uninterrupted jerking or shivering during the clonic phase may gradually resolve, but tonic spasm may occur again with a similar pattern of jerking and resolution. As the duration of the seizures increases, the movements and muscle contractions may become reduced despite continued generalized electrical activity in the brain.

Focal SE can be simple without loss of consciousness or complex with impaired consciousness. Jerking of one ipsilateral arm or leg or continuous clonic movements of one or two extremities can be observed. When confined to focal motor clonic seizures without Jacksonian march, it is often referred to as epilepsia partialis continua (EPC); the motor activity lasts for hours, days, weeks, or longer. Consciousness is not altered, but postictal weakness is frequent. In most cases, the ictal focus is cortical, and anticonvulsants help prevent generalization but are frequently ineffective at aborting the seizures. EPC is often caused by a structural lesion (e.g., tumor, chronic infarction) or a progressive neurodegenerative disease (particularly in children). Focal SE of all forms is often related to acute hemispheric lesions such as a hemorrhage or brain metastasis.

Focal SE can be simple without loss of consciousness or complex with impaired consciousness. Jerking of one ipsilateral arm or leg or continuous clonic movements of one or two extremities can be observed. When confined to focal motor clonic seizures without Jacksonian march, it is often referred to as epilepsia partialis continua (EPC); the motor activity lasts for hours, days, weeks, or longer. Consciousness is not altered, but postictal weakness is frequent. In most cases, the ictal focus is cortical, and anticonvulsants help prevent generalization but are frequently ineffective at aborting the seizures. EPC is often caused by a structural lesion (e.g., tumor, chronic infarction) or a progressive neurodegenerative disease (particularly in children). Focal SE of all forms is often related to acute hemispheric lesions such as a hemorrhage or brain metastasis.

Myoclonic SE is seen in patients after cardiac arrest or asphyxiation and consists of synchronous brief jerking of the limbs, face, or diaphragm. It can also be seen after electrical injury, drug intoxication, or decompression sickness and often denotes severe cortical laminar necrosis in association with thalamic and spinal cord injuries.

Myoclonic SE is seen in patients after cardiac arrest or asphyxiation and consists of synchronous brief jerking of the limbs, face, or diaphragm. It can also be seen after electrical injury, drug intoxication, or decompression sickness and often denotes severe cortical laminar necrosis in association with thalamic and spinal cord injuries.

7 Name general treatment measures for SE

An oral airway can be used if feasible, although most patients with prolonged SE may benefit from early endotracheal intubation.

An oral airway can be used if feasible, although most patients with prolonged SE may benefit from early endotracheal intubation.

Supplemental oxygen should be provided, large-bore proximal intravenous (IV) access obtained, and liberal hydration with normal saline solution initiated.

Supplemental oxygen should be provided, large-bore proximal intravenous (IV) access obtained, and liberal hydration with normal saline solution initiated.

Vital signs should be recorded regularly.

Vital signs should be recorded regularly.

A blood sample should be collected as soon as possible to rule out hypoglycemia.

A blood sample should be collected as soon as possible to rule out hypoglycemia.

A complete blood cell count, anticonvulsant levels, serum electrolytes, serum osmolarity, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, calcium, magnesium, phosphate, a drug screen, blood alcohol level, and arterial blood gas analysis should also be ordered.

A complete blood cell count, anticonvulsant levels, serum electrolytes, serum osmolarity, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, calcium, magnesium, phosphate, a drug screen, blood alcohol level, and arterial blood gas analysis should also be ordered.

If glucose testing reveals hypoglycemia, thiamine (100 mg IV) should be administered before the glucose bolus in patients with poor nutrition (e.g., patients with alcoholism).

If glucose testing reveals hypoglycemia, thiamine (100 mg IV) should be administered before the glucose bolus in patients with poor nutrition (e.g., patients with alcoholism).

Whenever appropriate, vasopressor agents should be used to support the circulation.

Whenever appropriate, vasopressor agents should be used to support the circulation.

If CNS infection is suspected, empirical treatment followed by early lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid analysis should be considered, especially in febrile children.

If CNS infection is suspected, empirical treatment followed by early lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid analysis should be considered, especially in febrile children.

EEG monitoring is particularly important in patients who have received neuromuscular blocking agents for intubation, as these agents may stop visible seizure manifestations despite electrical seizure activity in the brain.

EEG monitoring is particularly important in patients who have received neuromuscular blocking agents for intubation, as these agents may stop visible seizure manifestations despite electrical seizure activity in the brain.

10 What are the third-line treatments for SE ?

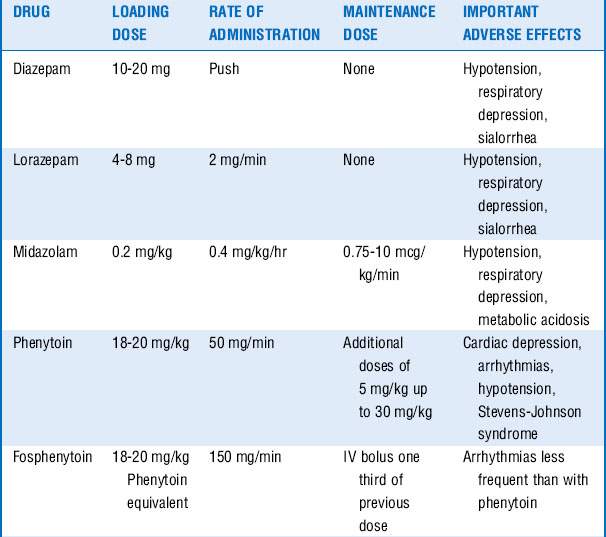

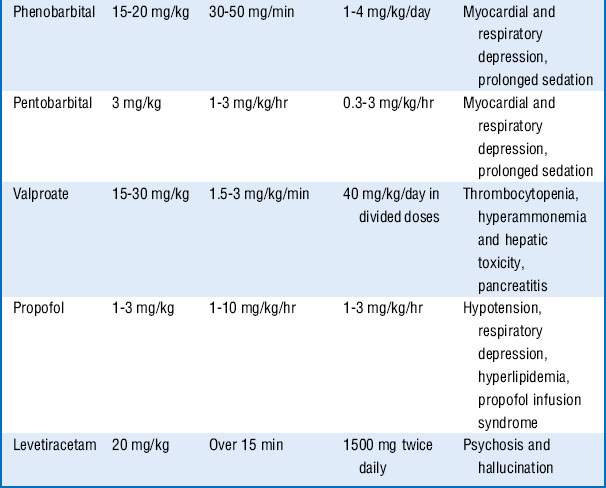

These drugs are often associated with hemodynamic changes when administered in the doses mentioned and may require vasopressors to maintain adequate blood pressures. Prolonged infusion of high doses of propofol may also result in a rare complication known as the propofol infusion syndrome, with refractory bradycardia, metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, renal failure, and cardiovascular collapse. Treatment includes discontinuation of the propofol infusion and supportive care. Additional drugs that may be tried, if seizures continue, include carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, topiramate, lamotrigine, and gabapentin. See Table 61-1.

14 What general measures should be considered after control of the seizures?

Key Points Status Epilepticus

1. SE is defined as seizures lasting ≥5 minutes or two or more seizures between which there is incomplete recovery of consciousness or function.

2. Morbidity and mortality are high in SE, and aggressive treatment strategies should be instituted immediately.

3. The most common cause of SE in a patient with known seizure disorder is low AED levels, whereas de novo SE is usually a manifestation of structural brain injuries or an illness that may require immediate diagnosis and treatment.

4. Treatment for SE is directed at stabilizing the patient’s condition, controlling the seizure, and identifying the cause. The underlying disease should be treated promptly.

5. First-line treatment to control the seizures often includes a benzodiazepine, for example, IV lorazepam. Second-line antiepileptic drug (phenytoin or fosphenytoin) can be given simultaneously with the first-line drug, or 1 minute after its administration if seizure persists. If third-line antiepileptic drugs (phenobarbital, valproate, or levetiracetam) do not stop the seizures, proceed to continuous infusion therapy with midazolam, pentobarbital, or propofol.

1 Bleck T.P. Intensive care unit management of patients with status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2007;48(Suppl 8):59–60.

2 Chen J.W., Wasterlain C.G. Status epilepticus: pathophysiology and management in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:246–256.

3 Costello D.J., Cole A.J. Treatment of acute seizures and status epilepticus. J Intensive Care Med. 2007;22:319–347.

4 DeLorenzo R.J., Pellock J.M., Towne A.R., et al. Epidemiology of status epilepticus. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;12:316–325.

5 Fountain N.B., Lothman E.W. Pathophysiology of status epilepticus. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;12:326–342.

6 Huff J.S., Fountain N.B. Pathophysiology and definitions of seizures and status epilepticus. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2011;29:1–13.

7 Lowenstein D.H., Bleck T., Macdonald R.L. It’s time to revise the definition of status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1999;40:120–122.

8 Lucas M.J., Leveno K.J., Cunningham F.G. A comparison of magnesium sulfate with phenytoin for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:201–205.

9 Mayer S.A., Claassen J., Lokine J., et al. Refractory status epilepticus: frequency, risk factors, and impact on outcome. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:205–210.

10 Mayhue F.E. IM midazolam for status epilepticus in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:643–645.

11 Neligan A., Shorvon S.D. Frequency and prognosis of convulsive status epilepticus of different causes: a systematic review. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:931–940.

12 Phillips S.A., Shanahan R.J. Etiology and mortality of status epilepticus in children. A recent update. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:74–76.

13 Pritchard J.A. The use of the magnesium ion in the management of eclamptogenic toxemia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1955;100:131–140.

14 Treiman D.M., Meyers P.D., Walton N.Y., et al. A comparison of four treatments for generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Veterans Affairs Status Epilepticus Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:792–798.

15 Wijdicks E.F., Parisi J.E., Sharbrough F.W. Prognostic value of myoclonus status in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:239–243.