Chapter 55 Staging and combining procedures

• Patient selection with specific attention to weight loss history, medical status, and nutritional assessment is the foundation for deciding when to combine procedures.

• Clinical setting and experience of the surgical team should be considered when planning combined procedures.

• Patient safety is paramount, and staging procedures should always be an option.

• Certain combinations of procedures complement each other, while others are best performed in a staged fashion because of opposing vectors of pull.

• The lower body lift is the cornerstone truncal contouring operation for the massive weight loss patient and often performed first in a staged plan.

Preoperative Evaluation of the Massive Weight Loss Patient

A relevant nutritional history should be obtained. The majority of weight loss patients will have adequate intake for the unstressed state. Major surgery, however, can increase the body’s nutritional requirements by 25% and many weight loss patients may have physical impedance to increasing oral intake.1 Please see Chapter 54 for further details.

Physical Examination

All aspects of a thorough physical exam should be included in the initial patient evaluation in order to fully appreciate the deformities and screen for residual medical problems. The massive weight loss patient will present with a wide range of physical anomalies. Body type (truncal versus peripheral obesity), remaining adiposity, rolls/folds and rashes should be noted. Body fat distribution will vary greatly in this patient population and will influence surgical options. Attention should be given to the patient’s skin tone and elasticity, as well as regional variations in skin elasticity. On the abdominal exam, make note of previous scars, the presence of any hernias, degree of diastasis, and overall laxity of the abdominal wall. To facilitate analysis of deformities in each anatomic region of the body, a four point rating scale can be applied. The Pittsburgh Weight Loss Deformity Scale is a tool to delineate the severity of deformities.2 An increased score correlates with a more severe deformity requiring a more extensive surgical procedure for correction.

Patient Selection

Weight Stability

Prior to body contouring surgery a patient should be weight stable for at least 3 months (usually occurs between 12 and 18 months after GBP). We define stability as no more than 2.5 kg (5 lb) change in weight per month over the previous 3 months. Nutritional homeostasis and a positive nitrogen balance are necessary to facilitate the healing process.3 Additionally, a more predictable outcome can be achieved when the patient is not actively losing weight.

Favorable BMI

A high BMI is associated with increased wound healing complications.4,5 As the patient’s BMI decreases, we are able to offer more safe surgical options and expect better esthetic outcomes.6 The best candidates have a BMI of 28 kg/m2 or less. We are more cautious in our level of intervention with patients who have a BMI between 29 and 32 kg/m2. Patients with a BMI between 32 and 35 kg/m2 should be selected with great care. If a patient in a high BMI range desires significant contouring, we recommend delaying the operation until further weight loss can be achieved. We work on a weight loss plan with the patient and nutritionist and schedule a 2–3 month follow up appointment. This way the patient will remain under your care and not feel abandoned; moreover, you are able to serve as a motivating force. Some patients in a high BMI range may benefit from a first stage breast reduction or simple panniculectomy if such a procedure would improve their ability to exercise and progress with further weight loss. For patients with a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2, our practice in most cases is to defer operations because of increased risk of complications and less potential for satisfying esthetic results.5,7 Patients in this BMI range may be offered a functional panniculectomy, with strict indications of severe panniculitis or a profoundly disabling pannus.

Nutritional Status

The importance of the nutritional status of the post-bariatric patient cannot be over-stressed.8–11 If the patient has symptoms of persistent nausea and vomiting, have them see their bariatric surgeon to rule out a stricture or a treatable cause. Because gastric bypass patients have altered gastrointestinal physiology and subsequent dietary issues, nutritional deficiencies are not uncommon.12 In our center, we require patients take at least 75–100 g of protein per day before elective body contouring surgery. A patient who is incapable of consuming 75 g of protein per day is often not a good surgical candidate and dietary modification is essential. Please see Chapter 54 on nutritional assessment.

Overview of Staging Strategies

The MWL patient is frequently a candidate for multiple body contouring procedures. These operations can generally be described as lengthy, technically demanding, and time-intensive versions of standard body contouring procedures familiar to most plastic surgeons. Determination of how many procedures to perform at one operation entails multiple factors (Table 55.1).

Patient Safety

First and foremost is patient safety. While there is no evidence to support a maximum operative time, some suggest that a 7-hour upper limit of total anesthesia time is reasonable for selected patients.13,14 In a clinical review comparing single-stage multiple procedure body contouring cases versus two-stage procedures, it was found that single-stage surgery averaged 8.4 hours while two-stage procedures averaged 7.4 hours for the first stage and 4.6 hours for the second stage, totaling 11 hours. Complications and wound healing problems were comparable between the two groups and the complication rates for the individual procedures remained constant when procedures were combined.15 Importantly, the majority of complications noted are local wound complications. Therefore, while the overall complication rate is higher for multiple procedure cases in well selected patients, the rate is equal to the sum of the complication rates for the individual procedures.

Surgeon Experience and Setting

While it may be feasible to do two or three procedures in a single stage, the surgeon should be guided by his or her level of experience, experience of the OR team, and treatment setting. Pitanguy set forth criteria when combining multiple procedures into one operation. These include: a skilled surgeon that is experienced at performing multiple procedures, anesthesiologists adept at handling these cases, and an operative team able to assist in the case.16 As mentioned earlier, combining procedures in well selected patients will increase the overall rate of local wound complications (additive based on “per procedure” complication rates), but the incidence of major complications is unchanged.17 Caution should be exercised in the surgery center setting should combined procedures be entertained, and the length of operative time and/or number of procedures performed in a single anesthetic may be regulated by legal code.

Considerations for Combining Procedures

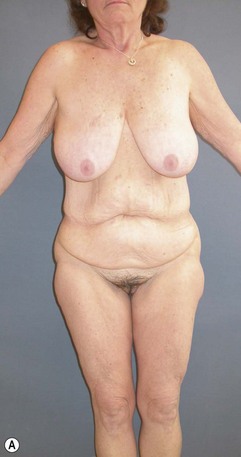

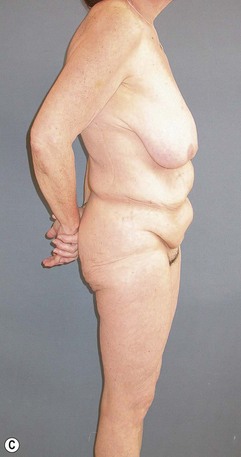

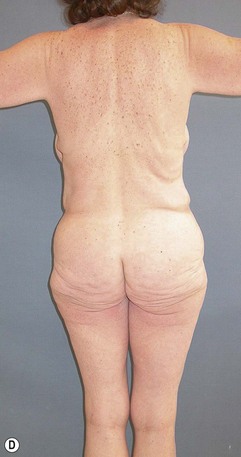

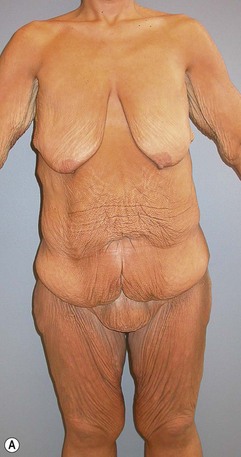

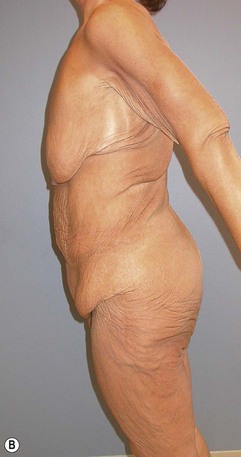

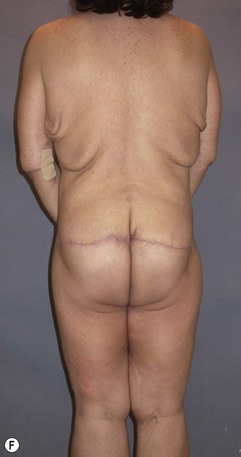

There are a number of body contouring procedures that can be combined in one operative setting. Below we will review some of the more common combinations and caveats to be aware of when assessing each patient. Detailed technical aspects of the procedures mentioned below appear in other chapters addressing the respective topics. Clinical examples of staged body contouring cases are shown in Figs 55.1–55.4.

FIG. 55.2 Brachioplasty photographs for the patient in Fig. 55.1 shown preoperatively (A), 1 year (B), and two years (C) postoperatively demonstrating maturation of the bicipital groove scar.

Upper Body Lift/Brachioplasty

Usually performed at a second stage, the upper body lift (UBL) targets the mid-back rolls and the lateral axillary rolls. Performing a brachioplasty with the UBL allows for a continuity of the scar pattern while minimizing creation of dog-ears. In the event that the combination of a brachioplasty and UBL result in a newly created t-point, then the procedures should be staged (see lateral view Fig. 55.4). An upper body lift can be readily combined with a mastopexy (Fig. 55.4).

Upper Body Lift/Lower Body Lift

An UBL and LBL should rarely be performed at the same time. These are two procedures with clearly opposing vectors that, when combined, limit the impact of each procedure performed individually. The amount of skin that can be resected from the UBL will be limited by the resection from the LBL. Although both are performed in the prone position, tackling these two problem areas at one time will likely lead to suboptimal results and may require a second operation to correct the residual skin laxity. It is this author’s preference to perform the LBL/abdominoplasty at the first stage and perform the UBL at a second stage (Fig. 55.4).

Abdominal Wall Reconstruction/Abdominoplasty

It is not uncommon for the plastic surgeon to encounter a massive weight loss patient with an incisional hernia. When approaching these patients, we first consider whether there has been sufficient weight loss to avoid excessive pressure on the repair exerted by a still obese intraabdominal compartment. The rates of postoperative wound complications and hernia recurrence are significant in patients with a BMI > 35.18 It is reasonable to recommend further weight loss and use of an abdominal binder for comfort before performing surgery on a large asymptomatic hernia, if necessary.

1 Van Way CW. Nutritional support in the injured patient. Surg Clin N Amer. 1991;71:537–548.

2 Song AY, Jean RD, Hurwitz DJ, et al. A Classification of Weight Loss Deformities: The Pittsburgh Rating Scale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1535–1554.

3 Halverson JD. Micronutrient deficiencies after gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Am Surg. 1986;52(11):594–598.

4 Matory WE, O’Sullivan J, Fudem G, et al. Abdominal surgery in patients with severe morbid obesity. Plast Recon Surg. 1994;94:976.

5 Vastine VL, Morgan RF, Williams GS. Wound complications of abdominoplasty in obese patients. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;42:33–35.

6 Coon D, Gusenoff JA, Kannan N, et al. Body mass and surgical complications in the postbariatric reconstructive patient: analysis of 511 cases. Ann Surg. 2009;249(3):397–401.

7 Choban PS, Flancbaum L. The impact of obesity on surgical outcomes: a review. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:592–593.

8 Charles P. Calcium absorption and calcium bioavailability. J Int Med. 1992;231(2):161–168.

9 Rhode BM, Arseneau P, Cooper BA, et al. Vitamin B-12 deficiency after gastric surgery for obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63(1):103–109.

10 Lash A, Saleem A. Iron metabolism: A comprehensive review. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1995;25(1):20–30.

11 Kushner R. Managing the obese patient after bariatric surgery: A case report of severe malnutrition and review of the literature. J Parenteral Enteral Nutr. 2000;24(2):126–132.

12 Halverson JD. Metabolic risk of obesity surgery and long-term follow-up. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55(2 Suppl):602S–605S.

13 Borud LJ. Combined procedures and staging. In: Rubin JP, Matarasso A. Aesthetic Surgery in the Massive Weight Loss Patient. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2007.

14 Safety considerations and avoiding complications in the massive weight loss patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:74S–81S. discussion 82S–83S

15 Hurwitz DJ, Agha-Mohammadi S, Ota K, et al. A clinical review of total body lift surgery. Aesth Surg J. 2008;28:294–303.

16 Pitanguy I, Ceravolo MP. Our experience with combining procedures in esthetic plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;71:56–62.

17 Coon D, Michaels J, Gussenoff JA, et al. Multiple procedures and staging in the massive weight loss population. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(2):691–698.

18 Reid RR, Dumanian GA. Panniculectomy and the separation-of-parts hernia repair: a solution for the large infraumbilical hernia in the obese patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(4):1006–1012.