Chapter 18

St Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

1. What are the electrocardiograph (ECG) criteria for the diagnosis of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)?

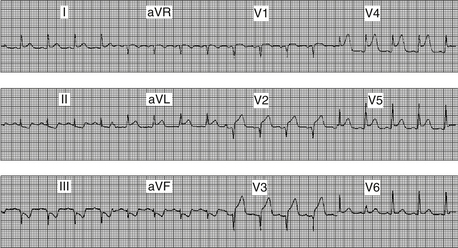

American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) criteria for STEMI consist of ST segment elevation greater than 0.1 mV (one small box) in at least two contiguous leads (e.g., leads III and aVF, or leads V2 and V3). The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) STEMI guidelines require 0.2 mV or greater ST elevation when analyzing leads V1 through V3 (but similarly, 0.1 mV elevation for other leads and/or territories). Figure 18.1 demonstrates the ECG finding of ST elevation in a patient with acute myocardial infarction.

American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) criteria for STEMI consist of ST segment elevation greater than 0.1 mV (one small box) in at least two contiguous leads (e.g., leads III and aVF, or leads V2 and V3). The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) STEMI guidelines require 0.2 mV or greater ST elevation when analyzing leads V1 through V3 (but similarly, 0.1 mV elevation for other leads and/or territories). Figure 18.1 demonstrates the ECG finding of ST elevation in a patient with acute myocardial infarction.

2. Is intracoronary thrombus common in STEMI?

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) refers to the strategy of taking a patient who presents with STEMI directly to the cardiac catheterization laboratory to undergo mechanical revascularization using balloon angioplasty, coronary stents, aspiration thrombectomy, and other measures. Patients are not treated with thrombolytic therapy in the emergency room (or ambulance) but preferentially taken directly to the cardiac catheterization laboratory for primary PCI. Studies have demonstrated that primary PCI is superior to thrombolytic therapy when it can be performed in a timely manner by a skilled interventional cardiologist with a skilled and experienced catheterization laboratory team.

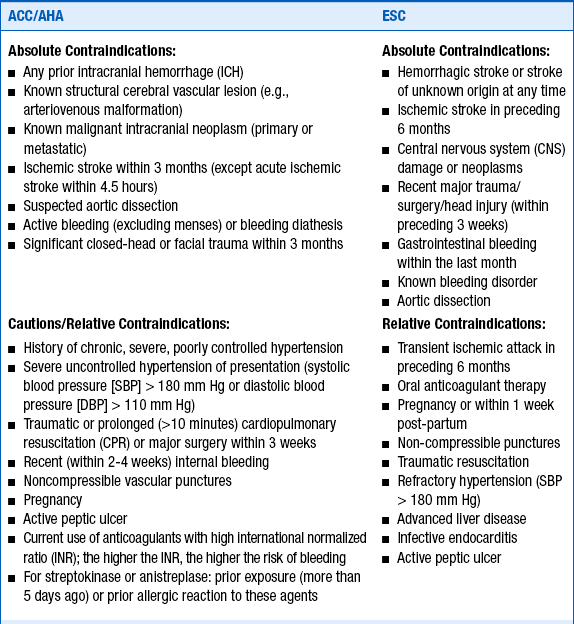

4. What are considered to be contraindications to thrombolytic therapy?

Several absolute contraindications to thrombolytic therapy and several relative contraindications (or cautions) must be considered in deciding whether to treat a patient with lytic agents. As would be expected, these are based on the risks and consequences of bleeding resulting from thrombolytic therapy. These contraindications and cautions are given in Box 18-1.

5. What is door-to-balloon time?

6. What is door-to-needle time?

7. In patients treated with thrombolytic therapy, how long should antithrombin therapy be continued?

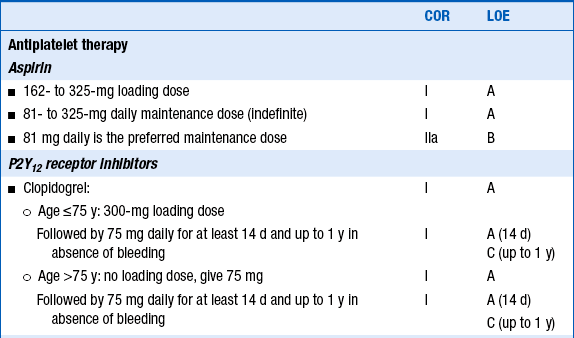

Patients who are treated with unfractionated heparin (UFH) should be treated for 48 hours. Studies of low-molecular-weight heparins (EXTRACT, CREATE) and of direct thrombin inhibitors (OASIS-6) have suggested that patients treated with these agents should be treated throughout their hospitalizations, up to 8 days maximum. Guidelines for adjunctive antiplatelet and antithrombin therapy in patients treated with thrombolytic therapy are given in Table 18-1.

TABLE 18-1

2013 ACCF/AHA guidelines for adjunctive antithrombotic therapy to support reperfusion with fibrinolytic therapy

Reproduced with permission from O’Gara P, Kushner FG, Ascheim D, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61(4):e78-e140.

8. Which patients with STEMI should undergo cardiac catheterization?

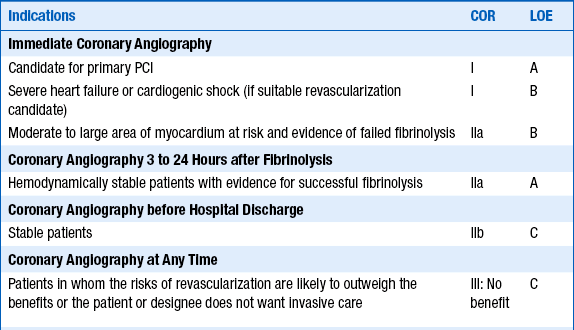

Patients with STEMI who should undergo immediate coronary angiography include those who are candidates for primary PCI, those with severe heart failure or cardiogenic shock (if they are suitable candidates for revascularization), and many of those with moderate to large areas of myocardium at risk and evidence of failed fibrinolysis. Cardiac catheterization is reasonable in hemodynamically stable patients with evidence of successful fibrinolysis. Recommendations from the 2011 ACCF/AHA/ Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) Guidelines on PCI regarding coronary angiography in patients with STEMI are given in Table 18-2.

TABLE 18-2

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI GUIDELINES ON PCI REGARDING CORONARY ANGIOGRAPHY IN PATIENTS WITH STEMI

Modified from Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 58:e44-e122, 2011.

9. Which patients with STEMI should undergo primary PCI?

Primary PCI should be performed in patients with STEMI who present within 12 hours of symptom onset, in patients with severe heart failure or cardiogenic shock, and in those with contraindications to fibrinolytic therapy. PCI can also be considered in those who have clinical evidence for fibrinolytic failure or infarct artery reocclusion after fibrinolytic failure, as well as those treated with likely successful fibrinolytic failure. Recommendations from the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guidelines on PCI regarding PCI in patients with STEMI are given in Table 18-3.

TABLE 18-3

RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI GUIDELINES ON PCI REGARDING PCI IN PATIENTS WITH STEMI

| Indications | COR | LOE |

| Primary PCI | I | A |

| STEMI symptoms within 12 hours | I | B |

| Severe heart failure or cardiogenic shock | I | B |

| Contraindications to fibrinolytic therapy with ischemic symptoms <12 hours | I | B |

| Asymptomatic patient presenting between 12 and 24 hours after symptoms onset and higher risk | IIB | C |

| Noninfarct artery PCI at the time of primary PCI in patients without hemodynamic compromise | III: Harm | B |

| Delayed or elective PCI in patients with STEMI (i.e., nonprimary PCI) | ||

| Clinical evidence for fibrinolytic failure or infarct artery reocclusion | IIA | B |

| Patient infarct artery 3 to 24 hours after fibrinolytic therapy | IIA | B |

| Ischemia on noninvasive testing | IIA | B |

| Hemodynamically significant stenosis in a patient infarct artery >24 hours after STEMI | 11B | B |

| Totally occluded infarct artery >24 hours after STEMI in a hemodynamically stable asymptomatic patient without evidence of severe ischemia | III: No benefit | B |

Modified from Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 58:e44-e122, 2011.

Rescue PCI is the performance of PCI after thrombolytic therapy has failed in a patient. Studies of rescue PCI versus medical management generally have shown a modest benefit with rescue PCI in appropriately selected patients. The problem with rescue PCI is that clinical and electrocardiographic criteria for predicting which patients have actually failed thrombolytic therapy (have not had successful lysis of coronary thrombosis and restoration of coronary perfusion) are imprecise. Thus, some patients with continued occluded arteries may not be referred for rescue PCI and some patients with successful reperfusion will be referred for unnecessary cardiac catheterization. As with the term facilitated PCI, some have advocated for elimination of the term rescue PCI.

12. Which patients should not be treated with beta-adrenergic blocking agent (β-blocker) therapy?

13. Which patients should be treated with nitrate therapy?

Sublingual (SL) nitroglycerin (0.4 mg) every 5 minutes, up to three doses, should be administered for ongoing ischemic discomfort. Intravenous nitroglycerin is indicated for relief of ongoing ischemic discomfort that responds to nitrate therapy, for control of hypertension, and for management of pulmonary edema. Nitrates should not be administered to patients who have received a phosphodiesterase inhibitor for erectile dysfunction within 24 to 48 hours (depending on the specific agent). Nitrates should also not be administered to those with suspected right ventricular (RV) infarction, systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg (or 30 mm Hg or more below baseline), severe bradycardia (less than 50 beats/min), or tachycardia (more than 100 beats/min) (Box 18-1).

14. Should patients with STEMI be continued on nonselective nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (other than aspirin) or COX-2 inhibitors?

15. What are the main mechanical complications of myocardial infarction?

Free wall rupture: Acute free wall rupture is almost always fatal. In some cases of subacute free wall rupture, only a small quantity of blood initially reaches the pericardial cavity and begins to cause signs of pericardial tamponade. Emergent echocardiography and immediate surgery are indicated.

Free wall rupture: Acute free wall rupture is almost always fatal. In some cases of subacute free wall rupture, only a small quantity of blood initially reaches the pericardial cavity and begins to cause signs of pericardial tamponade. Emergent echocardiography and immediate surgery are indicated.

Ventricular septal rupture: A ventricular septal defect (VSD) caused by myocardial infarction and septal rupture occurred in 1% to 2% of all patients with infarction in older series, though the incidence in the fibrinolytic age is 0.2% to 0.3%. Patients may complain of a chest pain somewhat different than their MI pain and will usually develop cardiogenic shock. A new systolic murmur may be audible, often along the left sternal border. Mortality without surgery is 54% in the first week and up to 92% within the first year.

Ventricular septal rupture: A ventricular septal defect (VSD) caused by myocardial infarction and septal rupture occurred in 1% to 2% of all patients with infarction in older series, though the incidence in the fibrinolytic age is 0.2% to 0.3%. Patients may complain of a chest pain somewhat different than their MI pain and will usually develop cardiogenic shock. A new systolic murmur may be audible, often along the left sternal border. Mortality without surgery is 54% in the first week and up to 92% within the first year.

Papillary muscle rupture: Papillary muscle rupture leads to acute and severe mitral regurgitation. It occurs in approximately 1% of STEMI patients. Because of the abrupt elevation in left atrial pressure, there may not be an audible murmur of mitral regurgitation. Pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock usually develop. Treatment is urgent or emergent mitral valve replacement (or in rare cases, mitral valve repair).

Papillary muscle rupture: Papillary muscle rupture leads to acute and severe mitral regurgitation. It occurs in approximately 1% of STEMI patients. Because of the abrupt elevation in left atrial pressure, there may not be an audible murmur of mitral regurgitation. Pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock usually develop. Treatment is urgent or emergent mitral valve replacement (or in rare cases, mitral valve repair).

16. What is the triad of findings suggestive of RV infarction?

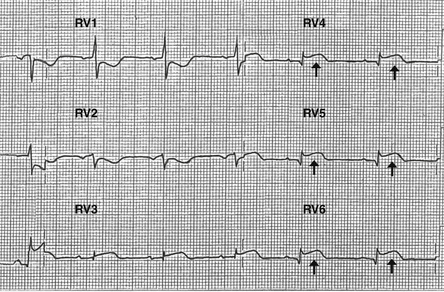

In patients with inferior MI, a right-sided ECG should be obtained. The precordial leads are placed over the right side of the chest in a mirror-image pattern to normal. The finding of 1 mm or greater ST elevation in leads RV4 through RV6 is highly suggestive of RV infarction (Fig. 18-2), although the absence of this often-transient finding should not be used to dismiss a diagnosis of RV infarction made on clinical grounds.

Figure 18-2 Right-sided leads demonstrating ST segment elevation (arrows) in leads RV4 through RV6, highly suggestive of right ventricular infarction.

17. Besides plaque rupture and thrombotic occlusion, what are other causes of STEMI?

Coronary vasospasm, such as what can occur with cocaine use

Coronary vasospasm, such as what can occur with cocaine use

Coronary artery embolism, such as in a patient with atrial fibrillation, left ventricular thrombus, endocarditis, or cardiac or valvular tumor

Coronary artery embolism, such as in a patient with atrial fibrillation, left ventricular thrombus, endocarditis, or cardiac or valvular tumor

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection

Ascending thoracic aortic dissection with compromise of the right coronary artery ostium

Ascending thoracic aortic dissection with compromise of the right coronary artery ostium

Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (stress cardiomyopathy, “broken heart syndrome”)

Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (stress cardiomyopathy, “broken heart syndrome”)

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Antman, E.M. ST-elevation myocardial infarction: management. In Libby P., Bonow R., Mann D., eds.: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2008.

2. Antman, E.M., Anbe, D.T., Armstrong, P.W., et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:E1–E211.

3. Antman, E.M., Hand, M., Armstrong, P.W., et al. focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;51:210–247. 2008

4. Zafari, A.M. Myocardial infarction. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/155919-overview. Accessed March 28, 2013

5. Gibson, C.M., Carrozza, J.P., Laham, R.J. Primary PCI versus Fibrinolysis (Thrombolysis) in Acute ST Elevation (Q Wave) Myocardial Infarction: Clinical Trials. Available at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/primary-percutaneous-coronary-intervention-versus-fibrinolysis-in-acute-st-elevation-myocardial-infarction-clinical-trials. Accessed March 28, 2013

6. Reeder, G.S., Kennedy, H.L., Rosenson, R.S. Overview of the Management of Acute ST Elevation (Q Wave) Myocardial Infarction. Available at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-acute-management-of-st-elevation-myocardial-infarction. Accessed March 28, 2013

7. Van de Werf, F., Ardissino, D., Betriu, A., et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. The Task Force on the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:28–66.