chapter 44 Sports medicine

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

Sports medicine encompasses healthcare for the exercising individual. The first associations for sports medicine practitioners appeared in the second half of the twentieth century (for example, the American College of Sports Medicine was founded in 1954 and the Australian Sports Medicine Federation was founded in 1963). For much of the twentieth century there was a perception that the major scope of sports medicine was care for the elite athlete. This perspective has even led to the cynical view that because injuries are common in sports, athletes should be characterised with groups such as smokers as being responsible for their own medical conditions.1 In recent years, it has become increasingly apparent that the benefits of exercise in general (and most sporting activities) far outweigh the risks in terms of injuries.2 Lack of physical activity, along with tobacco smoking and poor diet, is one of the three great reversible risk factors for disease in Western societies.3 While the scope of sports medicine still involves care of high-level athletes, its potential for helping society as a whole is just beginning to be realised.

Exercise prescription for the general population is that people should be physically active for more than 30 minutes on at least 5 days per week.2 (See also Ch 9, Exercise as therapy.) Sports medicine helps people to adhere to this prescription.

Musculoskeletal conditions can tend to be trivialised when viewed alongside other medical conditions that can lead to death and greater disability. However, by successfully managing these so-called ‘minor’ musculoskeletal injuries, sports medicine can enable ongoing exercise, which is critical for prevention of diabetes, heart disease, cancer and osteoporosis.4 The sports medicine attitude towards elite athletes of ‘keeping them on the field’ should also be applied to the rest of the population, in keeping them from becoming physically inactive.

Certain symptoms or body parts (e.g. knee pain) in sports medicine are easily amenable to clinical diagnosis and in these situations an attempt at diagnosis should be made. For other symptoms or body parts (e.g. low back pain), clinical diagnosis is notoriously inaccurate.4 This most certainly does not mean that every patient requires imaging,5 but instead that a management plan in most instances can be implemented based on a functional (rather than anatomical) diagnosis.

ANKLE SPRAIN

THERAPEUTICS

Nutrition and supplements

Prevention

KNEE INJURIES

Although knee MRI is more sensitive than clinical examination for certain conditions, because the knee is an accessible peripheral joint it is generally possible for an experienced clinician to make an accurate diagnosis of many knee injuries using history and clinical examination. For a GP assessing a knee injury it is most important to recognise the diagnostic possibilities from the history (Table 44.1) and to be aware of which clinical diagnoses can be made without the need for imaging or specialist assessment.

TABLE 44.1 Diagnosing the major knee injuries (clinical and imaging)

| Diagnosis | Clinical diagnosis | Investigations |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear | History of suddenly giving way. Experienced examiners can confirm with Lachman’s and pivot shift tests in most cases | MRI useful for high-level athletes with haemarthrosis when early diagnosis is required |

| Posterior cruciate ligament tear | Contact injury to the ground (on a flexed knee) or clash of knees (AFL ruckmen). Positive posterior drawer | Usually not necessary |

| Medial collateral ligament tear | Contact valgus injury, increased valgus stress | Usually not necessary |

| Tibio-fibular sprains/posterolateral complex injuries | Generally hyperextension mechanism (rare injury) | MRI to assess severity and whether surgery may be required (only required in severe cases) |

| Meniscal tears | Combination of medial or lateral pain and joint-line tenderness, mechanical symptoms, effusion and positive McMurray’s test | MRI scanning useful for confirming that surgery is indicated |

| Articular cartilage injuries | Knee effusion and history of locking or catching may indicate a significant lesion | X-ray to assess overall state of knee degeneration. MRI for pinpointing specific lesions, but X-ray is more likely than MRI to alter management |

| Knee inflammatory or infective conditions | Knee effusion, pain, fever, no history of trauma (or history of invasive procedure, e.g. injection or arthroscopy) | X-ray and pathology tests indicated (FBC, ESR, C-reactive protein, uric acid) |

| Patellar tendinopathy (or Osgood-Schlatter syndrome in adolescents) | History of sporting activity, gradual onset of pain, tenderness at either end of the patellar tendon | Ultrasound or MRI may assist with prognosis but do not generally alter management. Use X-ray instead in adolescents |

| Patellar tendon rupture | Sudden-onset injury, inability to support weight | Investigations indicated before surgery (ultrasound or MRI) |

| Hamstring insertional tendinopathy | Tenderness on medial side below joint line | Usually not necessary |

| Iliotibial band syndrome | History of running (or cycling), pain on slow running. Tenderness on lateral side above joint line | Usually not necessary |

| Patellofemoral pain | Pain with the knee bent (sitting or squatting) | Usually not necessary |

| Prepatellar bursitis | History of kneeling or landing on kneecap. Swelling cannot be balloted underneath the patella | Usually not necessary |

| Patellofemoral instability | Patellofemoral apprehension, history of dislocations | X-ray (with skyline view of patellofemoral joint) helpful |

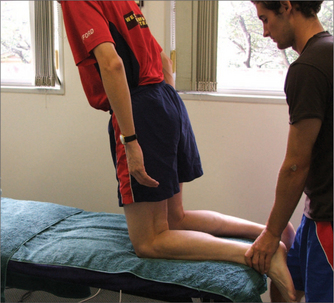

Clinical diagnosis of some injuries such as those to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) can be difficult for examiners who lack regular exposure to managing such injuries. However, a GP with a special interest in sports injuries and who is confident with using the Lachman (Fig 44.1) and pivot shift tests can often make this diagnosis. It is equally appropriate, when this diagnosis is suspected, to refer for MRI or specialist assessment when the diagnosis is in doubt. Although modern radiological techniques such as MRI can assist in the diagnosis of knee injuries, there is a tendency for overuse of investigations in cases where the diagnosis can be clearly established using clinical examination alone.5 It is important to remember that a high incidence of abnormality in normal asymptomatic knees is detected on knee MRI.12 In general the attitude towards investigation of knee injuries should fall somewhere between the potential mismanagement in an emergency department when a normal knee X-ray is used to declare that the injury is ‘minor’, and the modern (equally inappropriate) tendency to use MRI scanning to confirm every clinical diagnosis.

KNEE MENISCAL TEARS AND ARTICULAR CARTILAGE LESIONS

These indications should not be altered by the presence of in-substance signal change in the meniscus on an MRI scan. The information gained from MRI can be useful to avoid or delay surgery in a patient with knee pain due to low-grade articular cartilage degeneration. A recent controversial but landmark randomised controlled trial cast serious doubt on the value of knee ‘chondroplasty’ (smoothing of roughened areas of degenerate chondral surfaces) for mild–moderate degenerative articular cartilage change, showing no improvement with chondroplasty compared with placebo surgery.13 Although the authors claimed that many thousands of unnecessary arthroscopies are performed each year, there has been no reaction from orthopaedic surgery bodies, or insurance companies, to limit the indications for this potentially lucrative procedure.14 There is something of a role for arthroscopic management of certain chondral lesions, but the indications should probably be limited to cases in which there are loose bodies, mechanical symptoms of locking, or recurrent large effusions rather than knee pain with evidence of degenerative change on X-ray or MRI.

Where there are degenerative changes in the knee causing pain (but not to a degree that indicates that joint replacement is needed), the best management is to recommend moderate activity, quadriceps strengthening, glucosamine and chondroitin tablets and hyaluronic acid injections. Hyaluronic acid injections are normally given as a series of 3–5 × 2–3 mL injections weekly. While evidence indicates that outcomes are improved in knee osteoarthritis,15 the patient and their insurer must decide whether the possible benefits are worth the expense of the treatment.

ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT INJURIES

The knee anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury is rightly considered the most important acute diagnosis of the sporting knee because of its frequency and devastating impact on athletes. However, it is worth bearing in mind that an unstable ACL is a condition that affects the ability to participate in multidirectional sports and has relatively minimal effect on straight-line sports and everyday activities. Although the absolute number of ACL injuries occurring is greater in males (due to the greater likelihood of them playing at-risk sports),16 numerous studies have shown that the relative risk for ACL injury in females in much greater when they play the same sports.17,18

The most common mechanisms of ACL injury are:

The clinical diagnosis of ACL instability can be made in most cases using the Lachman and pivot shift tests. With the Lachman test (Fig 44.1), the amount of anterior drawer at 30° of flexion is relevant, but the ‘end point’ feel to movement is even more important for determining an intact ACL. When the pivot shift test is performed on a deficient ACL the tibia can be subluxed forward in internal rotation (relative to the femur) with an extended knee, and relocates with passive flexion. Successful use of these tests requires substantial exposure to examining stable and unstable knees, which is normally not part of medical school curriculum. Most sports physicians and orthopaedic surgeons who treat knee injuries can make the diagnosis clinically, particularly in either chronic cases or in the immediate acute scenario (on the sideline). The most difficult time to diagnose an ACL injury is in the days immediately after the injury, when there may be a large, tense haemarthrosis. At this time the accuracy of MRI examination may be greater than that of an experienced examiner. The natural history of an ACL injury is that the ligament generally heals in a suboptimal position, meaning that the knee is prone to instability (and therefore secondary cartilage injuries) during twisting movements.

After a diagnosis of ACL injury has been made, the patient is faced with difficult decisions about surgical reconstruction and whether to return to twisting sport. Younger patients are more likely to fail conservative treatment for ACL injuries. However, even surgical reconstruction cannot promise a completely normal knee. On return to sports such as football after reconstruction, the player has a four- to ten-fold increase in the risk of re-injuring the ACL (on either the graft or the contralateral side),19 and further surgery for cartilage injuries is not uncommon. The choice of graft for ACL reconstruction is made by the surgeon, but there have been many randomised controlled trials comparing the two most popular choices (patellar tendon graft and four-strand hamstring tendon grafts). A consistent finding has been equivalent levels of function and patient satisfaction for each type of graft, but with trends towards greater stability in the patellar tendon graft groups and less secondary morbidity from the graft site in the hamstring tendon groups.20 This means certain patients can be recommended to have certain grafts based on their relative needs for stability versus avoiding morbidity, but either graft choice is satisfactory in the hands of an experienced knee surgeon.

Management of the major knee injuries is summarised in Table 44.2.

TABLE 44.2 Recommended management (conservative versus surgical) for the major knee injuries

| Diagnosis | Conservative management | Surgical management |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear | In patients who do not have symptomatic instability, older athletes and/or those prepared to avoid multidirectional sports | ACL reconstruction is the management of choice for the young athlete who wishes to continue with multidirectional sports |

| Posterior cruciate ligament tear | Usually rest for 6–8 weeks is sufficient | Rarely indicated (?only when combined with posterolateral instability) |

| Medial collateral ligament tear | Rarely indicated (?high-level athletes with complete ruptures at the tibial insertion) | |

| Tibio-fibular sprains/posterolateral complex injuries | Minor lateral ligament sprains can recover with 2–6 weeks’ rest | Biceps tendon ruptures and/or combined lateral and posterior cruciate ligament injuries (rare) are managed surgically |

| Meniscal tears | Degenerative tears in the older athlete that do not give rise to mechanical symptoms can be managed conservatively | Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy is generally the treatment of choice for mensical tears. Meniscal repair can occasionally be successful in acute peripheral tears in younger athletes |

| Articular cartilage injuries | Almost all mild–moderate articular cartilage injuries (extremely common) should be managed conservatively, even though complete cure is unlikely | Arthroscopic surgery for articular cartilage lesions is probably over-performed (as it also fails to cure), although it is still indicated when there are mechanical symptoms such as locking. Total knee replacement in severe cases |

| Patellar tendinopathy | Physiotherapy, eccentric strengthening, activity within pain limits and some other therapeutic treatments (although COX-2 inhibitors and cortisone are not recommended) | Rarely indicated |

| Patellar tendon rupture | Treat surgically | Acute surgical repair is the most appropriate treatment |

| Osgood-Schlatter syndrome (in adolescents) | Activity within pain limits, calf and gluteal strengthening, reassurance | Rarely indicated (?when impingement caused by excessive ossification) |

| Hamstring insertional tendinopathy | Anti-inflammatory gel, cortisone injection, eccentric strengthening | Occasionally indicated for chronic cases with bursa formation |

| Iliotibial band syndrome | Cortisone injection, avoidance of aggravating activities (e.g. downhill jogging) | Indicated for cases resistant to conservative treatment |

| Patellofemoral pain | Physiotherapy, taping, strengthening | Rarely indicated (?when there is persistent knee joint effusion) |

| Prepatellar bursitis | Aspiration and cortisone injection (± antibiotics) | Indicated for cases resistant to conservative treatment |

| Patellofemoral instability | Physiotherapy, bracing, strengthening | Indicated for recurrent dislocations |

| Knee infections or inflammatory conditions | Cortisone injections for proven inflammatory conditions (e.g. gout) | Hospital admission (antibiotics, lavage) for knee joint infections |

TENDON INJURIES

Tendon injuries make up a large proportion of musculoskeletal pain in both athletes and the general community. The most common form is ‘tendinopathy’, which was previously but inaccurately known as ‘tendinitis’ when it was thought that these were inflammatory conditions.22,23 It is now best to think of tendinopathies as degenerative conditions although, fortunately, the degenerative change is semi-reversible. Some of the most common forms of tendinopathy are tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis), rotator cuff tendinopathy, De Quervain’s wrist tendinopathy, adductor (groin) tendinopathy, Achilles tendinopathy and patellar tendinopathy (‘jumper’s knee’). The other common condition related to tendinopathies is plantar fasciitis, which strictly speaking is an enthesopathy, not a tendinopathy, as there is no muscle directly attached to the plantar fascia (and hence it is not a tendon).

The most common variety of tendinopathy is insertional (affecting the bone–tendon interface), although Achilles tendinopathy is an exception as it most commonly affects the mid-tendon substance. Some types of insertional tendinopathy are prone to intra-tendinous calcification. Insertional tendinopathies appear to be a combined ‘underuse–overuse’ injury, with the weakened under-surface of the tendon not bearing enough load and the normal outer portion of the tendon often overloaded.23 The key underlying management is to recommend moderate loads that the injured tendon can withstand, rather than continuing with overloads or recommending complete rest. Sudden increases in load are risky for all tendons and hence complete inactivity is risky for tendon injury (as return to ‘normal’ activity will represent a sudden increase in load). This paradigm explains why tendinopathy is common in middle-aged people who suddenly take up exercise after a period of inactivity.

The middle-ground approach to tendinopathy is moderate loading within pain limits, followed by gradual increases in load as the weakened section of the tendon repairs itself. Some experts recommend exercising through the pain barrier, with complete immobilisation now out of favour and considered overly conservative.18 Eccentric strengthening (loading as the tendon is lengthening) appears to be the best type of specific rehabilitation exercise.24

Because inflammation and impingement are not generally considered significant pathologies in this condition, NSAIDs and cortisone injections are not generally recommended.25 Other newer treatment options successfully used for patellar or similar tendinopathies include nitrate patches,25–28 extracorporeal shock-wave therapy29 and polidocanol injections.25 Nitrate patches are those used to treat angina, with the lowest dose (5 mg/24 h) cut into quarters (NITRO-DUR® or Minitran™) and applied daily to the affected body part (Fig 44.2).

ROTATOR CUFF TENDINOPATHY AND ‘TENNIS ELBOW’

The two most common tendinopathies in the upper limb affect the supraspinatus tendon in the shoulder and the common extensor origin at the elbow. Supraspinatus tendinopathy is a special case as the phenomenon of impingement is generally associated with this condition. It is clinically important to assess how much of the patient’s pain is due to the intrinsic pathology of tendon, compared with secondary impingement. Weakness on rotator cuff strength testing can suggest tendon damage, but shoulder ultrasound is probably the best way to accurately differentiate this from impingement. If impingement is the predominant cause of pain, NSAIDs and cortisone injections are indicated. For intrinsic tendinopathy, scapular stabilising exercises and nitrate patches are more-specific treatments.

LOWER-LIMB TENDINOPATHIES

Management of lower-limb tendinopathies follows similar principles, although because the tendons bear heavy loads, cortisone injections are riskier and should generally be avoided. The key management principle is graduated loading, including eccentric (lengthening only) strengthening exercises.24 An example of an eccentric exercise is shown in Fig 44.3 for the hamstring muscle group. For patellar tendinopathy (‘jumper’s knee’) the exercises are best done on a decline board (30° downslope), which encourages loading of the patellar tendon while lengthening only.31 Other exercises should strengthen or mobilise other deficiencies in the lower limb (e.g. calf and gluteal strengthening and hamstring stretching). Very few patients require total rest from weightbearing or immobilisation. Surgery for many lower-limb tendinopathies has limited success, although it is indicated for tendon rupture.

In adolescents, similar conditions are common but with more tendency to self-limitation as they are epiphyseal overloads. They are, unfortunately, known by their cumbersome eponymous names such as Osgood-Schlatter disease (at the tibial tubercle just below the knee) and Sever’s disease (below the Achilles attachment on the calcaneus).

GROIN INJURIES

Groin injuries are often due to chronic tendinopathy (particularly of the adductor muscle group), although the differential diagnosis of groin pain is extremely complicated.32 Chronic groin pain is often due to osteitis pubis,33 which is probably a bony stress overload lesion at the end stage of insertional tendinopathy. The standard treatment of chronic groin overuse injuries is reduction of load (rather than total rest) to a level where the pain is not worsening. Fortunately, many football players can continue to play once a week and limit their training without aggravating a chronic groin injury. In the off-season, jogging is generally encouraged, followed in order by faster running, maximal sprinting, kicking from a standing start, change of direction movements and then kicking on the run. Surgery is sometimes indicated, including hernia repair and adductor tenotomy.34 In addition to unresolved chronic pain, the indication for adductor tenotomy includes painful reduction of range of passive hip abduction, as surgery can correct this. A hernia repair is indicated if there is pain and clinical or imaging (usually ultrasound) evidence of a hernia or posterior inguinal wall deficit.35

DRUGS IN SPORT

WADA enforces the principle of strict liability because there is generally no reasonable doubt that a drug discovered within an athlete’s urine or blood sample (taken under a strict protocol) was present within the athlete’s system, yet it would be far too difficult, in the majority of cases, to prove intent to cheat beyond reasonable doubt. Strict liability for doping offences is controversial, although the WADA Code does offer the athlete some opportunity to consider the unique circumstances of each case.

SPORTS PSYCHOLOGY

MENTAL HEALTH

Anxiety and depression are common among high-performing athletes. The unbridled joy often publicly displayed when winning is the other side of the coin of the intense disappointment often borne privately when having lost or performed poorly. Furthermore, ambition or anxiety about performance can lead elite athletes to set extraordinarily high expectations or participate when they possibly should not. Such concerns are also a significant contributor to the risk of taking performance-enhancing drugs and all the health and legal problems that this entails.

CONCLUSION

Sports medicine is an emerging field that particularly has scope for community (non-hospital) practice, and hence it is very relevant to general practice. GPs are now aware that lack of exercise is a major risk factor for many diseases. There is a move towards treating non-exercisers as the medical profession treats smokers—that doctors must try to convince these patient that their lifestyle choices are unhealthy and require changing. However, doctors who are correctly advising their patients that they must exercise need to be in a position where they can provide basic management of the injuries that may be associated with exercise. For this reason, the past ostracism of sports medicine by much of the mainstream medical community has been misplaced.36

Australia has been a world leader in the development of quality sports medicine practice, possibly because of the elevated status of professional sport in this country.36 However, in prevention of sports injuries and recognition of sports medicine as a specialty area, it has fallen behind other countries, most notably New Zealand.37,38 In Australia, only 50% of the population is physically active at recommended levels, meaning that physical inactivity may soon surpass cigarette smoking as the number one cause of preventable diseases.3

ASDMAC (Australian Sports Drug Medical Advisory Committee). http://www.asdmac.org.au.

Australasian College of Sports Physicians. http://www.acsp.org.au/.

Brukner P, Khan K. Clinical sports medicine, 3rd edn. Sydney: McGraw Hill, 2006. One of the world’s leading general sports medicine texts. Pitched at a perfect level for medical students, physiotherapists, general practitioners and doctors undertaking postgraduate study in sports medicine. For information: http://www.clinicalsportsmedicine.com/

injuryupdate, an Australian website on sports injuries. http://www.injuryupdate.com.au/.

Medical Journal of Australia, sports medicine papers. http://www.mja.com.au/Topics/Sports%20medicine.html.

National Sports Information Centre, Australian Institute of Sport. http://www.ausport.gov.au/nsic/index.asp.

1 Finer N. Rationing joint replacements: Trust’s decision seems to be based on prejudice or attributing blame [letter]. BMJ. 2005;331:1472.

2 Brukner P, Brown W. Is exercise good for you? Med J Aust. 2005;183(10):538-541.

3 Mokdad A, Marks J, Stroup D, et al. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238-1245.

4 Bigos S, Davis G. Scientific application of sports medicine principles for acute low back problems. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;24(4):192-207.

5 Orchard J, Read J, Anderson I. The use of diagnostic imaging in sports medicine. Med J Aust. 2005;183(9):482-486.

6 Ivins D. Acute ankle sprain: an update. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(10):1714-1720.

7 Haraguchi N, Toga H, Shiba N, et al. Avulsion fracture of the lateral ankle ligament complex in severe inversion injury: incidence and clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1144-1152.

8 Kerkhoffs GM, Struijs PA, Marti RK. Different functional treatment strategies for acute lateral ankle ligament injuries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD002938.

9 Predel HG, Giannetti B, Koll R, et al. Efficacy of a comfrey root extract ointment in comparison to a diclofenac gel in the treatment of ankle distortions: results of an observer-blind, randomized, multicenter study. Phytomedicine. 2005;12(10):707-714.

10 Quinn K, Parker P, de Bie R, et al. Interventions for preventing ankle ligament injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000018.

11 McGuine TA, Keene JS. The effect of a balance training program on the risk of ankle sprains in high school athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(7):1103-1111.

12 Beattie K, Boulos P, Pui M, et al. Abnormalities identified in the knees of asymptomatic volunteers using peripheral magnetic resonance imaging. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13(3):181-186.

13 Moseley J, O’Malley K, Petersen N, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:81-88.

14 Orchard J. Health insurance rebates in sports medicine should consider scientific evidence [editorial]. J Sci Med Sport. 2002;5(4):v-viii.

15 Strand V, Conaghan P, Lohmander L, et al. An integrated analysis of five double-blind, randomized controlled trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of a hyaluronan product for intra-articular injection in osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:859-866.

16 Orchard J, Chivers I, Aldous D. Seasonal and geographical analysis of ACL injury risk in Australia. Sport Health. 2005;23(4):20-27.

17 Arendt E, Agel J, Dick R. Anterior cruciate ligament injury patterns among collegiate men and women. J Athlet Train. 1999;34(2):86-92.

18 Arendt E, Dick R. Knee injury patterns among men and women in collegiate basketball and soccer. NCAA data and review of the literature. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(6):694-701.

19 Orchard J, Seward H, McGivern J, et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament injury in Australian footballers. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):196-200.

20 Anderson A, Snyder R, Lipscomb A. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A prospective randomized study of three surgical methods. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(3):272-279.

21 Bayat M, Delbari A, Almaseyeh MA. Low-level laser therapy improves early healing of medial collateral ligament injuries in rats. Photomed Laser Surg. 2005;23(6):556-560.

22 Khan KM, Cook JL, Bonar F, et al. Histopathology of common tendinopathies. Update and implications for clinical management. Sports Med. 1999;27:393-408.

23 Orchard J, Cook J, Halpin N. Stress-shielding as a cause of insertional tendinopathy: the operative technique of limited adductor tenotomy supports this theory. J Sci Med Sport. 2004;7(4):424-428.

24 Alfredson H, Pietila T, Jonsson P, et al. Heavy-load eccentric calf-muscle training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:360-366.

25 Paoloni J, Orchard J. The use of therapeutic medications for soft-tissue injuries in sports medicine. Med J Aust. 2005;183(7):384-388.

26 Paoloni J, Nelson J, Murrell G. Topical glyceryl trinitrate application in the treatment of chronic supraspinatus tendinopathy. A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(6):8-16.

27 Paoloni J, Appleyard R, Nelson J, et al. Topical glyceryl trinitrate treatment of chronic noninsertional achilles tendinopathy. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86A(5):916-922.

28 Paoloni J, Appleyard R, Nelson J, et al. Topical nitric oxide application in the treatment of chronic extensor tendinosis at the elbow: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(6):915-920.

29 Gerdesmeyer L, Wagenpfeil S, Haake M, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for the treatment of chronic calcifying tendonitis of the rotator cuff: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(19):2573-2580.

30 Bisset L, Paungmali A, Vicenzino B, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials on physical interventions for lateral epicondylalgia. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(7):411-422.

31 Cook J, Khan K. What is the most appropriate treatment for patellar tendinopathy? In: MacAuley D, Best T, editors. Evidence-based sports medicine. London: BMJ; 2002:422.

32 Fricker P, Taunton J, Ammann W. Osteitis pubis in athletes: infection, inflammation or injury? Sports Med. 1991;12(4):266-279.

33 Verrall G, Slavotinek J, Fon G. Incidence of pubic bone marrow oedema in Australian rules football players: relation to groin pain. Brit J Sports Med. 2001;35(1):28-33.

34 Orchard J, Read J, Verrall G, et al. Pathophysiology of chronic groin pain in the athlete. Intern Sports Med J. 2000;1(1):134-147.

35 Orchard J, Read J, Neophyton J, et al. Groin pain associated with ultrasound findings of inguinal canal posterior wall deficiency in Australian Rules footballers. Br J Sports Med. 1998;32(2):134-139.

36 Orchard J, Brukner P. Sport and exercise medicine in Australia. Med J Aust. 2005;183(7):383.

37 Orchard J, Leeder S, Moorhead G, et al. Australia urgently needs a federal government body dedicated to monitoring and preventing sports injuries. Med J Aust. 2007;187(9):505-506.

38 Orchard J, Finch C. Australia needs to follow New Zealand’s lead on sports injuries. Med J Aust. 2002;177(1):38-39.