Chapter 15. Sports injuries

Sports medicine is essentially a type of occupational health medicine and this should not be forgotten just because many of the patients are well-known public figures.

No injury is unique to athletes and the conditions described in this chapter could equally well be described elsewhere. The chapter deals with the particular problems of the sporting world and describes lesions that occur more often in sporting activities than everyday life.

Psychology and the athlete

Many sports injuries are treated by orthopaedic surgeons because of their involvement with trauma, but sports medicine is very different from the rest of orthopaedic surgery. For one thing, an athlete who is 100% fit will be unhappy – an athlete needs to be not less than 110% fit, at least in his or her own estimation, and will strive for 120%. This belief, coupled with the athlete’s drive to achieve goals beyond the scope of ordinary people, may loosen their hold on reality and prevent them understanding that their body is made of the same stuff as ordinary mortals.

A further problem is that many athletes have a compulsive–obsessional approach to their sport. A cyclist or a runner who does not put in the allotted number of miles per week will feel uneasy and fear their performance will be permanently impaired. In this regard the behaviour of some athletes is similar to that of other compulsive neuroses such as alcoholism, compulsive gambling and anorexia nervosa. Fortunately, most sportsmen and women have a healthy approach to their sport, but compulsive individuals do exist and must be recognized at an early stage.

For many well-balanced athletes fitness is an integral part of their way of life and self-image. Occasional recreational athletes may feel that their sporting activities distinguish them from their more everyday contemporaries. To find that their sporting prowess has been taken away can make both groups clinically depressed and produce a similar reaction to bereavement or the loss of a limb.

Ageing

Athletes have great difficulty in accepting the ageing process. Ageing athletes – over 30 years of age – may be so convinced of their own eternal youth that they will seek medical advice to find out why they cannot run as fast or jump as high as they did 10 years earlier. The simple explanation that they are ‘growing old’ will not be believed.

Other patients may, unconsciously, be a little more subtle in their approach to advancing age and look to injury as an excuse for graceful retirement or a gradual descent to a lower level of performance. Neither of these conditions can be treated by operation.

The ageing process cannot be denied. However rigorous the training programme and however assiduously it may be pursued, hair still goes grey, skin wrinkles, articular surfaces become less resilient and more fragile, muscles waste, tendons weaken and soft tissue degenerates. These are biological facts that cannot be altered by training or ‘dedication’.

For these reasons the approach to the athlete cannot be based on organic features of the injury alone. Many athletes may have a perfectly straightforward organic injury but to treat that without understanding the feeling of the athlete towards his or her own physical fitness will lead to disillusionment on both sides.

Practical and professional considerations

Sports medicine presents practical and ethical problems. In other specialties doctors are in no doubt that they are the patient’s medical attendant, but in the field of sports medicine there may be more concern for the success of the player’s club than for the long-term future of the player.

The welfare of any patient has to be considered not only from the short-term point of view but also from the long-term. Considerable pressure is sometimes applied to the doctor by the team manager or club, as well as by the player, to achieve a good short-term result without regard for the long-term.

Enabling a player to take part in an important match soon after a serious injury or operation, for example, could have harmful long-term effects. To complicate matters, the players themselves are not always in a position to disagree with their club official and may enthusiastically embrace the prospect of osteoarthritis in middle age if only they can play on Saturday.

The need for rapid results and the fast return to sport after injury also means that athletes demand priority over other patients. If health service resources are in short supply, it is hard to justify treating a recreational athlete in preference to a wage-earner who cannot work. Injured sportsmen are seldom ill or disabled in the common sense of the word, yet their powerful motivation will often find a way through the normal channels to be treated in preference to patients with genuine organic illness. This can lead to ill-feeling when resources are scarce.

To avoid this problem, sports clinics treating athletes only are often set up outside hospitals and orthopaedic departments, but this leads to the paradox that in some places the only way to receive prompt treatment for a musculoskeletal disorder is to declare that it was the result of a sporting injury rather than an accident at work.

These observations do not detract from the need for a specialized service for sportsmen or deny the existence of injuries specific to individual sports. Provided that the doctor can come to terms with the psychological aspects of sportsmen and women and the practical problems of establishing a clinic for sports injuries, sports medicine is a rewarding and fascinating specialty.

The conditions described below are commonly seen in athletes but are not unique to them.

Injuries to muscles

Musculotendinous injuries

• Ruptures of the muscle belly.

• Haematoma in the muscle belly.

• Rupture of the musculotendinous junction.

• Rupture of the tendon.

• Tendinitis.

• Tears at the muscle insertion.

Ruptures of the muscle belly

Clinical features

Rupture of a muscle is felt as a tearing sensation. Swelling and tenderness at the site of the rupture follow within hours, and bruising about 24 h later. The bruising is caused by bleeding from the ends of the ruptured muscle and can be quite dramatic, even alarming.

On examination a defect can be felt in the muscle belly and the belly becomes prominent as the muscle contracts. The swelling can occasionally be mistaken for a soft tissue mass. The rectus femoris and hamstrings are the muscles most often affected.

Haematoma

A haematoma in a muscle is a serious lesion, sometimes called a ‘Charley horse’ for no obvious reason. The lesion usually follows direct trauma or, more rarely, a tear of the central fibres of the muscle. The quadriceps is most commonly affected.

As the blood in the haematoma becomes organized it interferes with normal muscle function and in some patients the haematoma becomes ossified, which restricts muscle movement severely. The mass of bone usually resolves within 2 years of injury but may have to be excised.

Ossification can occur in any haematoma, but is said to be more common if the muscle is mobilized too rapidly after the injury.

Treatment

The immediate treatment for a ruptured muscle, as for other soft tissue injuries, is to cool the limb with ice wrapped in a towel to prevent cold injury, elevate the limb, apply gentle compression and avoid contracting the torn muscle.

Ruptures of a muscle belly cannot be repaired successfully. The tears take at least 6 weeks to heal with sound fibrous tissue and the healing process cannot be accelerated artificially. Operation causes more soft tissue destruction, sutures will not hold in the torn muscle ends, and rehabilitation is delayed. Ultrasound reduces localized swelling and passive joint movement maintains joint mobility.

Active contraction of the ruptured muscle is harmful during the first 6 weeks, but physiotherapy can then be started to increase muscle power gradually while maintaining joint mobility. When normal power and mobility have been obtained, a gradual return to full sporting activities is permitted. If this regimen is not followed, a re-rupture of the muscle is likely.

Musculotendinous ruptures

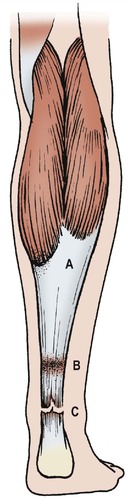

Like ruptures of the muscle belly, rupture of the musculotendinous junction is felt as a tearing sensation followed by pain and bruising (Fig. 15.1). The commonest site is the medial belly of the gastrocnemius, which can be torn by a sharp dorsiflexion of the ankle, often during a game of squash or tennis. The area of tenderness is localized and a defect can be felt in the muscle belly.

|

| Fig. 15.1

Sites of damage to the calf and Achilles tendon: ( A) partial rupture of the medial belly of the gastrocnemius; ( B) paratenonitis; ( C) rupture of the Achilles tendon.

|

Treatment

Treatment is the same as for other soft tissue injuries; i.e. ice, elevation and compression. Ultrasound will reduce swelling, and joint movement should be maintained. Pain after this injury lasts for a predictable 8 weeks and complete recovery is the rule.

Emergency treatment of soft tissue injuries:

Rest

Ice (wrapped in a towel if from the deepfreeze)

Compression

Elevation.

Injuries to muscle insertions

Tennis elbow, golfer’s elbow and jumper’s knee are described on pages 371, 372 and 424.

Tendons

Tendons, like muscles, can be ruptured by sudden violent contraction. The commonest tendon to rupture is the Achilles tendon, but the tendons to the long head of biceps and supraspinatus may also rupture.

Achilles tendon rupture is described on page 273.

Paratenonitis

The paratenon becomes inflamed by repeated friction. The paratenon of the Achilles tendon and extensor muscles of the wrist are commonly affected, and this may be due to poor technique such as holding a racquet wrongly.

Treatment

Paratenonitis at the heel is made worse by running on hard surfaces and wearing shoes with a worn heel. Proper footwear or a soft heel-pad may resolve the problem.

At the wrist, if attention to racquet technique is ineffective, rest in a splint is usually helpful, but unacceptable to athletes.

Injection of a steroid preparation into the paratenon – but not the tendon – is also effective. In persistent cases the paratenon must be explored and adhesions between it and the underlying tendon divided.

Tendinitis

The patellar tendon can be irritated or its central fibres torn by repeated jumping, particularly in high jump training and basketball, to produce a condition similar to jumper’s knee. The patient will experience pain in the patellar tendon, worse on quadriceps contraction, but without localized tenderness. Steroid injection around, but not into, the tendon may be helpful.

Treatment

Treatment is by rest and anti-inflammatory drugs. Do not inject steroids into the tendon or it may rupture. Eccentric exercises are beneficial.

Bones and joints

Fatigue fractures

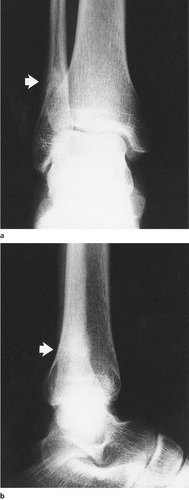

Fatigue fractures in the metatarsals follow overuse and repeated loading. March fracture of the second metatarsal is the best known (p. 100) but fatigue fractures are also seen in the tibia and fibula of long-distance runners and other athletes in whom repeated stress is placed on the lower leg (Fig. 15.2 and Fig. 15.3). Spondylolisthesis, a fatigue fracture of the pars interarticularis, occurs in athletes who hyperextend their spine, such as fast bowlers in cricket and javelin throwers.

|

| Fig. 15.2

(a), (b) Fatigue fracture of the lower end of the fibula in a road runner.

|

|

| Fig. 15.3

(a), (b) Fatigue fracture of the tibia in a runner, shown by sclerosis of the tibial cortex.

|

Treatment

Treatment consists of rest until the fracture has united. Brace immobilization may allow the patient to start physiotherapy sooner.

Cruciate ligament injuries

Cruciate ligament injuries are common on the sports field and are dealt with on page 420.

Breast-stroke knee

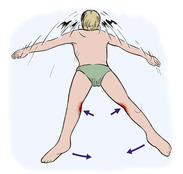

Breast-stroke swimmers adduct the legs forcefully against the resistance of the water (Fig. 15.4). This produces a chronic irritation of the distal insertion of the medial ligament, which becomes tender and painful when a valgus strain is applied.

|

| Fig. 15.4

Breast-stroke knee. The breast-stroke action stresses the medial ligaments and may cause pain and tenderness.

|

Treatment

Apart from modifying training there is little to offer for this lesion.

Jogger’s knee

Between the ages of 30 and 40 years the articular cartilage begins to lose its resilience and becomes more brittle. Repeated loading of the articular cartilage, as in road running or jogging, can cause pain in the weight-bearing joints, particularly the knee and patellofemoral joint.

Treatment

The symptoms can be relieved by running on soft ground instead of road or by wearing properly designed running shoes with well-padded heels. In persistent cases it may be necessary to advise the patient to stop. Moulded insoles (orthoses) may help by changing the forces on the heel when it strikes the ground.

Other injuries

A full catalogue of the many injuries that can be caused by specific sporting activities would be very long indeed.

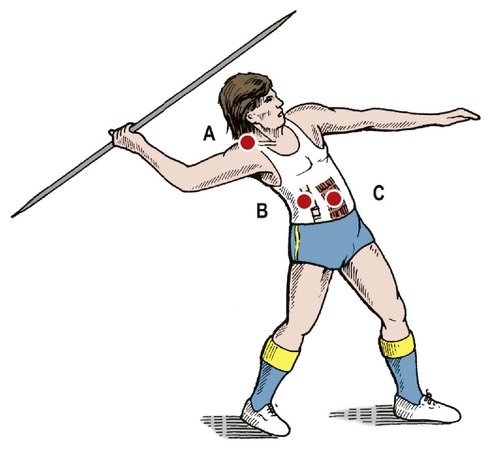

Javelin throwers can disrupt the acromioclavicular joint by the violent forward movement of the shoulder (Fig. 15.5). No treatment will restore the joint to complete normality.

|

| Fig. 15.5

Injuries in javelin throwers: ( A) subluxation of the acromioclavicular joint; ( B) hyperextension of the spine, which may cause spondylolysis; ( C) rupture of the rectus abdominis.

|

Archers develop a similar lesion. On the Tudor warship the Mary Rose, many skeletons were found with exaggerated muscle attachments around the right shoulder girdle and disrupted acromioclavicular joints. It is likely that these were archers.

Fast bowlers can rupture their external oblique muscle during delivery. The injury is occasionally seen in other throwing sports.

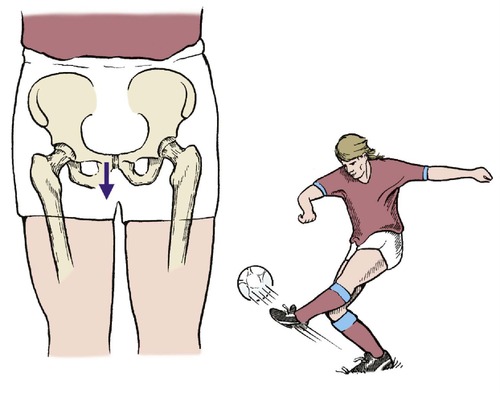

Footballers may damage the pubic symphysis through kicking the ball at speed while twisting on one leg (Fig. 15.6). This can be resistant to treatment.

|

| Fig. 15.6

Strain on the pubic symphysis in a footballer.

|

Footballers also develop symptoms from small inguinal hernias.

Repetitive stress injuries

Many sports injuries are the result of repeated stress, often from training techniques. This group of injuries includes tenosynovitis, fatigue fractures and a host of other problems caused by repeating the same movement over and over again in an attempt to achieve perfection. Once identified, the problem can usually be corrected by changing the training technique.

Prevention

Prevention of sports injuries

• Adequate ‘warm-up’.

• Gradual return after lay-off from injury, off-season, etc.

• Correct footwear and clothing.

• Good protective wear – helmets, etc.

Warming up

Sporting injuries can be minimized by correct training, proper warm-up and using the correct equipment. In particular, muscle and tendon injuries can be reduced by ensuring that players do not go into full athletic activity without stretching the muscles adequately beforehand.

If athletic training is discontinued, suppleness, strength and stamina are lost, in that order. Because suppleness is so important in the prevention of muscle and tendon injuries, and because preseason training is so often neglected, injuries are far more common in the first half of the first match of the season than in any other. An adequate warm-up and muscle stretching routine before a match is essential.

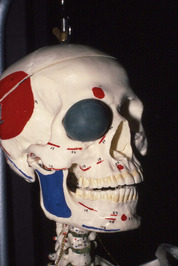

Protective wear

Protective wear is important if patients are engaged in a sport in which they are likely to sustain an impact, such as in boxing or cricket. Correct training shoes help to prevent jogger’s knee and plastic spectacles should always be worn when playing squash; the squash ball fits neatly into the orbit and several eyes are lost every year from this injury (Fig. 15.7).

|

| Fig. 15.7

A squash ball fits neatly into the orbit. Protective spectacles should be worn when playing squash.

|

Sport, like life, is dangerous!

Case reports

More and more people are playing sport for longer and longer. Unfortunately, as mentioned, a number of injuries can occur. These include not only the acute injuries but also the more chronic injuries that result from overuse, poor technique or bad equipment. The following examples illustrate some of these common chronic injuries.

Patient A

An 18-year-old army recruit suddenly developed right foot pain following prolonged exercise. The pain was worse with activity and relieved slightly by rest.

He was able to walk but found running and marching difficult. He attended the sick bay and was provided with simple analgesics but this failed to settle the pain. He continued with the vigorous army exercises, but was unable to cope and had to stop after the first week.

Clinical examination confirmed pain over the second metatarsal with localized soft tissue swelling but no other abnormality. Radiographs confirmed a periosteal reaction and a possible hairline fracture. This was treated as a stress fracture with rest, avoidance of further injury and a graduated rehabilitation programme.

The patient was able to return to sporting activities and the army regime after 3 months.

Patient B

A keen club runner who frequently ran between 30 and 50 km (20–30 miles) per week noted increasing pain in the calf muscles of the left leg. He noticed that he was able to run a couple of miles before he developed a cramping sensation in the calf, which failed to resolve.

He was forced to rest and the pain did settle slightly, although he was left with a dull aching sensation in the calf. He described the calf as feeling ‘woody, hard’ when painful. When not running he had no symptoms and was able to continue with his normal lifestyle.

He consulted the local physiotherapists and was informed that he had shin splints and was treated with an orthosis in his shoe. He attempted to continue running, but had a recurrence of the pain after running 2 miles.

When reviewed by the orthopaedic surgeon, intracompartmental pressure studies confirmed an elevation of the compartment pressure with exercise. He subsequently underwent a decompressive fasciotomy which cured the pain and allowed him to continue with his running career.

Patient C

A 45-year-old company director took up competitive tennis after a break of 10 years. Being a highly competitive individual he practised and competed regularly but noted an increasing pain over the lateral aspect of his right elbow with most ground shots.

The local physiotherapist made the diagnosis of a ‘tennis elbow’ and provided him with an epicondylitis strap. This failed to relieve his pain as he continued to play tennis on a regular basis.

When asked about the equipment that he used it was clear that he continued to use his old racquet, which had a very narrow grip. He had also changed his technique and grip recently. The pain settled in his elbow with the appropriate conservative treatment of physiotherapy, rest and alteration in not only the technique but also the type of racquet that he was using.

Summary

These three cases represent common chronic sporting injuries. With a sudden increase in intensity or duration of activity the bone can fatigue and fracture. This type of stress fracture will only heal when the limb is rested and an appropriate rehabilitation training programme is instituted.

Similarly, overuse injuries are common, especially with runners, and the use of poor equipment or bad technique can result in injury to the joint. Simple treatment of the injury without removing the cause fails to resolve these injuries.