CHAPTER 129 Spondylolysis

INTRODUCTION

Spondylolysis is a devastating injury to a young athlete. It is the most frequent lumbar spine injury in the adolescent population. Sixty percent of all adolescent athletes experience low back pain of some sort, but only 6% are diagnosed with an acute spondylolysis.1–3 An acute spondylolysis is a stress fracture of the pars articularis or a complete breakthrough of the pars articularis. Most patients who suffer from spondylolysis have low back pain on extension, but the pain may radiate into the legs as it worsens. If the patient is placed in a lumbosacral corset, there may be immediate relief of the pain with almost complete relief of the pain within 5 days; yet if the athlete returns to the activities, the pain will return immediately. This chapter’s goal is to explore the biomechanics, diagnostic work-up, and treatment for spondylolysis.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

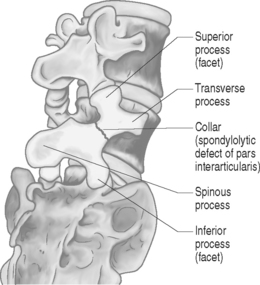

The lumbar vertebra is made up of an anterior portion, the vertebral body, and the posterior elements, which are made up of the pars as well as the facet and joints and spinous process. The lamina connects them together. When a normal person performs most activities, it is either in the standing or sitting position. The bulk of these pressures on the spine are on the vertebral body and very little is on the posterior elements, i.e. the pars and facet joints. When athletes do extension and rotation, such as winding up to pitch a baseball, back flips in gymnastics, or kicking in soccer, extra force and weight are placed on the posterior elements, which can cause one of two things to happen. The most common result is that the facet joints of the posterior elements become inflamed and develop an overuse syndrome, termed facet joint synovitis.4,5 The other result of overuse becomes a stress fracture or spondylolysis. The only way to differentiate between facet synovitis and spondylolysis is with radiographic testing, which will be described later in this chapter.6 The partes themselves are the thinnest parts of the neural arch and are the most susceptible for a fracture within the posterior elements. A recent study by Chosa et al. demonstrated this in a three-dimenstional, mechanical study of the lumbar spine.7 Their study showed that the stress in the pars intra-articularis was least with compression alone but stronger under compression with lateral bending along with rotation and extension. It was the highest with extension and rotation. Consequently, repetitive extension with rotation should be considered a relatively high-risk factor for the development of spondylolysis.8 This is no surprise to the practitioner who sees most of these injuries in the athletes who perform extension–rotation movements, such as offensive linemen in football, wind-up players in cricket, as well as pitchers in female softball and male hardball.

DIAGNOSIS

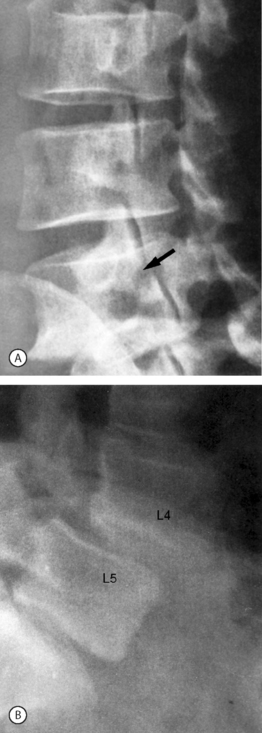

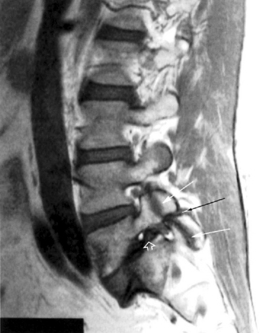

The initial diagnostic test should be a plain radiographic examination of the lumbar spine including anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique views. The AP perspective can rule out scoliosis. The obliques are done to look for a ‘Scottie dog’ fracture of the neck or the pars (Fig. 129.1, 129.2A,B) A pars defect can be detected in the lateral view, but its primary benefit is to identify spondylolisthesis.9 Plain radiographs may be normal when there is only a stress reaction and not frank fatigue leading to fracture or when the spondylolysis has only recently occurred. The next step would be to perform a single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) multiplanar bone scan. If the SPECT scan and plain films are positive, the evidence suggests a stress fracture. When the plain films are negative and the SPECT scan is positive then a stress reaction is the likely diagnosis. If the SPECT scan and plain films are negative the diagnosis is probably not spondylolysis.10,11 The third test of choice for this condition is a computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 129.3). A recent study by Stretch et al. showed that the CT scan was very sensitive in showing nonunion and healing6. Using thin-slice CT, they were able to show with repeat studies of the CT scans complete healing in 8 out of 9 injured athletes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not of much benefit, even using bone windows. In a recent study Sherif and Mahfouz attempted to place the epidural space in an anterior position between the dura mater and spinous process to diagnose spondylolysis.12 This allows for different tissues to contrast with each other to brighten the bone views. Unfortunately, the MRIs were not very beneficial even with the new technique.12 Additionally an MRI might identify if there is concurrent disc disease or spinal cord pathology (Fig. 129.4). This obviously will not be observed with X-ray or SPECT scan. The CT scan may show some disc disease, but not to the same degree as MRI. If the X-ray is negative, either CT or SPECT scan can be perfomed. If negative, either CT or SPECT scan can be performed. If a bone scan is performed and is positive, the patient can be treated symptomatically. At the end of the treatment, the patient can have a CT scan.13 If the CT scan shows complete union, then no further treatment is necessary. Other testing that may be needed for adolescents with back pain are a rheumatoid work-up with CBC and sedimentation rate, HLA-B27 and C-reactive protein looking for spondylitis, which could mimic the pain of spondylolysis. If there is a question with continued symptomatology without much relief from the current treatment, diagnostic injections, under fluoroscopy, of the medial branch nerve or the pars itself would be of benefit and give enough information to identify the source of the pain. For patients needing to return to play immediately, this is definitely a treatment option for short-term activity, but not for a long-term solution.

TREATMENT

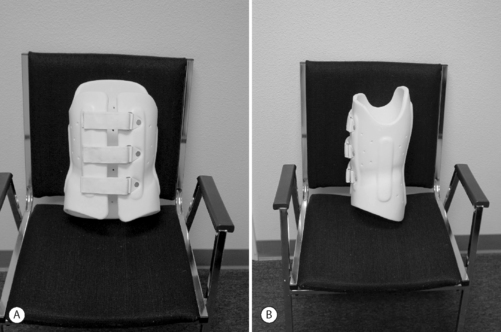

The treatment of choice is as follows. Symptom abatement is the most accurate indication of healing. Initially, the patients should be banned from exacerbating activities and put into a lumbosacral corset (Fig. 129.5).14 Fifteen years ago, patients were placed in plastic thoracolumbosacral orthosis (TLSO) with a thigh cuff to achieve spine extension (Fig. 129.6). There were compliance problems with this bulky brace. The pain subsides so the patient will not wear it. These braces were not only uncomfortable but unsightly, leading to poor compliance. A more simple solution involves the use of a lumbosacral corset with metal stays or the new lumbosacral corsets that are now available (Fig. 129.7). The brace should be worn 24 hours a day or at least while awake. The patients should become asymptomatic within 4 weeks. If pain relief is achieved, an aggressive stretching and strengthening program involving the upper back muscles, abdominal muscles, hip, and the lower limbs (Table 129.1), as well as a stretching program is begun (Table 129.2).15 Back extension activities or even flexion activities are prohibited for the first 8 weeks, which allows time for the pars to heal. During the 8 weeks when they are resting, the patients can do upper body strengthening, and possibly some lower extremity strengthening. They may be able to use an exercise bike or perform any other type of aerobic activity (Table 129.3) as long as the brace is on and the back has no flexion or extension movements. If the bone scan was positive and the X-rays and CT are negative, the patients can return to activity within 4 weeks. If the CT scan is positive, it would be wiser to wait 8–12 weeks before returning to activities, although there have been no studies that show if there is any correlation between rest and return to activity in healing of the pars itself.16 The authors performed SPECT scans on patients at the time of the injury, 3 months afterwards, and up to a year later. This study showed that there was no correlation between healing on the SPECT scans and their symptoms. It was found that one-third of patients were asymptomatic despite having positive bone scans. No patients were symptomatic with a negative bone scan. A recent study with the CT scan as previously mentioned showed that 40% of the people were asymptomatic completely, with 60% asymptomatic and 40% still with some pain when they returned to activities with normal CT scans. These findings indicate that the symptoms will improve faster than the radiographic findings. With no studies proving that resting for 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, or even 2 years has any improvement on the CT scan healing, the standard of care is to treat the patient symptomatically. If it is during the season relevant to the patients’ activities, return the patients to their activity as soon as they are asymptomatic, with a strengthening program and some type of lumbar support that reduces extension. If some pain lingers, the patients are to rest completely for 8 weeks after the season is ended, and before they start to work out in the following season. Figures 129.5–129.7 show the different types of corsets available. Other treatments besides rest, corsets, and strengthening program include medications. These should include antiinflammatory medications, which do nothing directly for healing but may help the patient’s pain. In this population, the analgesic medication tramadol should be used; it has a 6-hour duration unlike the short-acting opiates, which only have 4 hours’ duration. The opiates have more side effects such as constipation, addiction, and mental status changes. Muscle relaxants may play a role early on but once the brace is worn all the spasm symptoms will be gone within the first week or two. Modalities such as massage, electrostimulation, and ultrasound are all of benefit. If they make patients feel better, so that they may attend class and perform other activities, these modalities may be encouraged although they have no effect on healing. Parental guidance is very important as the children may refuse to wear the braces. When they feel better, and without the deformity seen in scoliosis, it is much more difficult to persuade patients to wear the braces. In patients who have an X-ray that shows permanent pars fracture already present or a break in the neck, a bone scan with SPECT scan should be performed. If the bone scan with the SPECT is negative, this indicates it is an old lesion and that the pain is either coming from the lesion or from the joints themselves. Such patients should be first placed in a corset for 4–8 weeks, but many continue with activities and perform a strengthening program. If they continue to have pain, they are the candidates for injection directly into the pars, or medial branch blocks to relieve the pain. In most of these cases, a CT scan will show the lesions. If the bone scan is positive, these patients will need to be braced and given a CT for diagnosis of injury and another CT scan 3 months later. At this time, if the CT scan is showing healing, they should be ready to continue activities. If, at 3 months, the CT scan shows no change from the original CT scan, this would indicate it is a permanent pars lesion and that treatment is completely based on symptomatology, and therapy and injections would be the primary treatment. Surgery is a last resort.

| Strengthening |

| Lumbar stability examination |

| Hip flexion, extension, abductors, adductors |

| Rotational extensors exercise |

| Closed kinetic lower extremity strengthening exercises |

| Sport-specific exercises |

Initially, lumbar stabilization exercises are performed with the addition of the hip muscles finally leading to more advanced exercises.8

| Flexibility |

| Hamstring muscles |

| Iliopsoas muscles |

| Abdominal muscles |

| Hip extensor muscles |

The above muscles may have restrictions which need to be resolved to achieve proper biomechanics and relieve the stress on the pars.7

| Aerobic non-loading |

| Swimming |

| Bike |

| Jog in pool |

| Minor loading |

| Walking |

| Stair climbing |

| Elliptical |

Early exercises including non-loading aerobic are listed above with graduation to minor loading exercises.7

SURGICAL INTERVENTION AND INJECTIONS

If a patient has continued pain, a treatment with medial branch block would be diagnostic as well as therapeutic. If two blocks are done, a medial branch neurotomy may be contemplated. If this gives relief from pain, the patient can return to play. If this doesn’t work, fusion may be performed or direct repair of the pars may be undertaken.17 There is literature showing that this is of benefit. Obviously, when patients are adolescents with a fusion, there is a risk that the level above the fusion will become degenerative much sooner, causing early degenerative disc disease.18–20 Therefore, surgery should only be performed in cases of severe pain causing a patient to be unable to attend school or obviously in a case of spondylolysis deteriorating into spondylolisthesis and spondylolisthesis going beyond grade 1 to grade 3 or 4.21

1 Gregory PL, Batt ME, Kerslake RW. Comparing spondylolysis in cricketers and soccer players. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(6):737-742.

2 Kraft DE. Low back pain in the adolescent athlete. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49(3):643-653.

3 Lundin DA, Wiseman DB, Shaffrey CI. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in the athlete. Clin Neurosurg. 2002;49:528-547.

4 DePalma MJ, Slipman CW, Siegelman E, et al. Interspinous bursitis in an athlete. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2004;86(7):1062-1064.

5 Miller SF, Congeni J, Swanson K. Long-term functional and anatomical follow-up of early detected spondylolysis in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):928-933.

6 Stretch RA, Botha T, Chandler S, et al. Back injuries in young fast bowlers – a radiological investigation of the healing of spondylolysis and pedicle sclerosis. S Afr Med J. 2003;93(8):611-616.

7 Chosa E, Totoribe K, Tajima N. A biomechanical study of lumbar spondylolysis based on a three-dimensional finite element method. J Orthop Res. 2004;22(1):158-163.

8 Mihara H, Onari K, Cheng BC, et al. The biomechanical effects of spondylolysis and its treatment. Spine. 2003;28(3):235-238.

9 Reitman CA, Gertzbein SD, Francis WRJr. Lumbar isthmic defects in teenagers resulting from stress fractures. Spine J. 2002;2(4):303-306.

10 Van der Wall H, Storey G, Magnussen J, et al. Distinguishing scintigraphic features of spondylolysis. Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(3):308-311.

11 Watanabe O, Hashimoto M, Tomura N, et al. [Evaluation of usefulness of bone SPECT for lumbar spondylolysis] (Japanese). Nippon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi. 2002;62(8):423-429.

12 Sherif H, Mahfouz AE. Epidural fat interposition between dura mater and spinous process: a new sign for the diagnosis of spondylolysis on MR imaging of the lumbar spine. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(6):970-973.

13 Campbell RS, Grainger AJ, Hide IG, et al. Juvenile spondylolysis: a comparative analysis of CT, SPECT and MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34(2):63-73.

14 d’Hemecourt PA, Zurakowski D, Kriemler S, et al. Spondylolysis: returning the athlete to sports participation with brace treatment. Orthopedics. 2002;25(6):653-657.

15 Stasinopoulos D. Treatment of spondylolysis with external electrical stimulation in young athletes: a critical literature review. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(3):352-354.

16 Iwamoto J, Takeda T, Wakano K. Returning athletes with severe low back pain and spondylolysis to original sporting activities with conservative treatment. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2004;14(6):346-351.

17 Lundin DA, Wiseman D, Ellenbogen RG, et al. Direct repair of the pars interarticularis for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2003;39(4):195-200.

18 Debnath UK, Freeman BJ, Gregory P, et al. Clinical outcome and return to sport after the surgical treatment of spondylolysis in young athletes. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2003;85(2):244-249.

19 McNeely ML, Torrance G, Magee DJ. A systematic review of physiotherapy for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Man Ther. 2003;8(2):80-91.

20 Ranawat VS, Heywood-Waddington MB. Failure of operative treatment in a fast bowler with bilateral spondylolysis. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(2):225-226.

21 Beutler WJ, Fredrickson BE, Murtland A, et al. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: 45-year follow-up evaluation. Spine. 2003;28(10):1027-1035. discussion 1035