Spleen

Appraisal

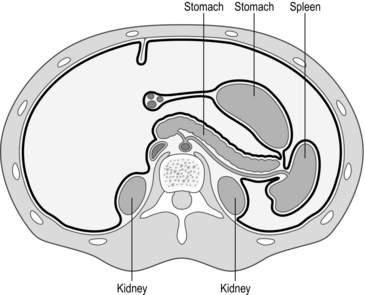

1. The spleen is an important organ, with both haematological and immunological functions (Fig. 18.1). Do not lightly remove it. Its haematological functions include the storage, maturation and destruction of red blood cells. Immunologically it produces peptides necessary for the phagocytosis of encapsulated bacteria (Streptococcus pneumonia, Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenza). It is a site of antibody synthesis and may be a reservoir for monocytes that are mobilized following tissue injury. When possible, conserve at least part of the spleen, as opposed to total splenectomy. This may protect against overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI).

2. Elective splenectomy is most commonly carried out for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) and haemolytic anaemias. Splenectomy is also required occasionally for other types of splenomegaly with hypersplenism and rarely for conditions such as cyst, abscess, haemangioma or splenic artery aneurysm. Splenectomy is sometimes carried out as a part of other operations, such as total gastrectomy and distal pancreatectomy. Indications are listed in Table 18.1.

Table 18.1

| Red cell causes | Hereditary spherocytosis |

| Sickle cell disease | |

| Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia | |

| Thalassaemias | |

| White cell causes | Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | |

| Leukaemia | |

| Platelet causes | Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) |

| TTP | |

| Other causes | Trauma |

| Cysts | |

| Abscesses |

3. The indications, preoperative preparation, surgical principles and aftercare are similar for both open and laparoscopic splenectomy.

4. Laparoscopic splenectomy is the standard approach for elective splenectomy for the majority of patients, with operative duration between 60 and 90 minutes, and a hospital stay between 1 and 2 days. There is controversy about its use when treating patients with very large spleens, in splenic trauma and its adequacy for removal of accessory spleens in ITP.

5. There are no absolute contraindications to laparoscopic splenectomy. Spleen size is a major factor. Massive splenomegaly presents difficulties in access, vision and manoeuvring the spleen. Identification of accessory splenic tissue may be less thorough than in open surgery but the long-term results are same. Obesity, peritoneal adhesions and the presence of inflammation also add to the difficulties.

6. The advantages of laparoscopic splenectomy include less postoperative pain, more rapid recovery and fewer respiratory complications when compared to open splenectomy. Long-term follow-up of patients with ITP and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, the two most common indications, have shown identical results to the open approach. The rate of conversion to open splenectomy varies from 0% to 19%. Haemorrhage is the most common reason for conversion, followed by difficulty in mobilizing the spleen due to adhesions or spleen size and injury to adjacent organs.

7. Open splenectomy should be reserved for failure of the laparoscopic technique, emergency splenectomy for trauma and when the necessary laparoscopic skills or equipment are not available.

8. Emergency splenectomy is indicated for traumatic rupture of the spleen, mostly following road traffic accidents and other blunt abdominal injuries. Enlarged spleens are at increased risk of rupture, which may occur spontaneously. Classically, patients are shocked, with pain in the left hypochondrium and shoulder-tip and evidence of left lower rib fractures. Urgent laparotomy is required to control bleeding if the patient remains unstable after initial resuscitation.

9. There is an increasing trend to non-operative management of splenic injuries, particularly in children. Lesser splenic injuries can be managed conservatively with vigilant clinical observation and blood transfusion. Appropriate patients are those less than 60 years of age, haemodynamically stable, with a blood transfusion requirement not exceeding 3–4 units and with computed tomography (CT) scan evidence that the spleen has not been fragmented. A grading system for splenic trauma is summarized in Table 18.2.

Table 18.2

A grading system of splenic trauma

| Grade I: capsular injury not actively bleeding | Non-operative |

| Grade II: capsular or minor parenchymal injury | Topical haemostatic agent |

| Grade III: moderate parenchymal injury | Suturing and haemostatic agent |

| Grade IV: severe parenchymal injury | Partial splenic resection |

| Grade V: Extensive parenchymal injury | Splenectomy |

10. Accidental splenic injury sustained during operations, such as left hemicolectomy, was formerly an indication for splenectomy, but the bleeding can usually be controlled by lesser means. Intra-operative splenic injury occurs in approximately 0.01% of open laparotomies and the incidence increases following reoperative surgery. Up to 10% of splenectomies performed are secondary to iatrogenic injury.

11. Preoperative splenic artery embolization may reduce the risk of intra-operative haemorrhage. This percutaneous radiological technique has been described in conjunction with open splenectomy, primarily in cases of massive splenomegaly. Other advantages of embolization include reduced splenic volume and avoidance of the risk of arteriovenous fistula from stapling across the splenic hilum. Embolization is most frequently performed on the day of surgery to reduce the discomfort associated with splenic ischaemia and infectious complications.

Prepare

1. Vaccinate patients 2 weeks prior to surgery to decrease the risk of post-splenectomy sepsis. Immunize against pneumococcal infections (Pneumovax II 0.5 ml IM/SC, Sanofi Pasteur) and Haemophilus influenza type b (Hib) and meningococcus group C infections (Menitorix 0.5 ml IM, GlaxoSmithKline).

2. Preoperative percutaneous splenic artery embolization is used in some units to reduce the risk of bleeding or decrease significant splenomegaly.

3. Give antibiotics (first generation cephalosporin) perioperatively. Ensure patients are adequately hydrated before surgery. Pneumatic compression stockings are routinely employed.

4. Correct anaemia, thrombocytopenia and coagulopathies preoperatively. Reserve packed red blood cells for all patients and platelets for thrombocytopenic patients. Preoperative medical therapy (e.g. IgG therapy or increasing steroids) may elevate platelet count transiently in ITP cases. Give parenteral steroid cover in patients with ITP or other haematological disease on long-term corticosteroids. Involve the haematologist in the pre- and postoperative care of the patient. If the platelet count is low, transfuse platelets intra-operatively after ligation of the splenic artery to prevent rapid sequestration.

5. A nasogastric tube may be needed to decompress a distended stomach, but is not routinely required.

6. Ensure you have explained and documented the advice given to patients on the risks of post-splenectomy sepsis.

LAPAROSCOPIC SPLENECTOMY

Access

1. Position the patient in a left lateral position. This position facilitates retraction of the stomach and omentum away from the spleen and improves access.

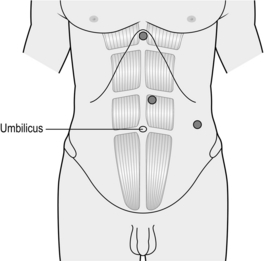

2. Create a pneumoperitoneum using a Veress needle technique at the umbilicus or an open technique at the camera port site. Exact port placement depends on the size of the spleen. For a normal-sized spleen place the 11-mm camera port above the umbilicus and to the left of the midline. Place a 5-mm port in the epigastrium and a 12-mm port for stapler and retrieval bag in the left lateral position as shown in Figure 18.2. An additional port for a fan retractor may be necessary.

Assess

1. Perform a systematic exploration looking for splenunculi (small nodules of splenic tissue away from the main body of the spleen), which may be found anywhere in the abdominal cavity, but are commonly located at the hilum of the spleen and adjacent to the tail of the pancreas. When identified, if the splenectomy is performed for conditions in which blood cells are sequestered in the spleen, remove all splenunculi immediately so they are not lost during subsequent dissection.

2. Use scissor diathermy or a harmonic scalpel to divide any omental adhesions to the lower pole of the spleen and the splenocolic ligament.

Action

1. Avoid grasping the spleen directly. Use open Johannes forceps to gently retract the spleen medially. Divide splenic attachments about 1 cm away from the spleen and use these attachments to retract the spleen. Continue the dissection laterally to divide the attachments to the lateral sidewall. Continue the dissection, using the harmonic scalpel or hook diathermy, from the inferior pole of the spleen to the superior pole. As the dissection progresses the spleen becomes more mobile and can be moved medially to expose the back of the splenic hilum.

2. Leave the splenophrenic ligaments at the top of the spleen to stop it falling into the abdominal cavity: these are divided once the spleen has been placed in the retrieval bag, immediately prior to its removal. It is important to clear the back of the splenic hilum carefully at this stage and identify the tail of the pancreas to avoid damaging it at a later stage.

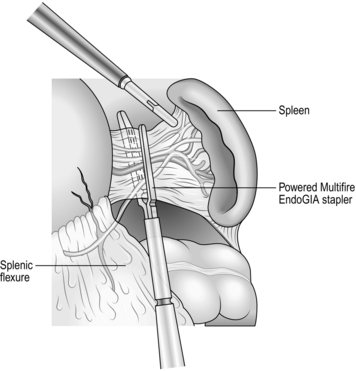

3. Return to the lower pole of the spleen and begin the medial dissection by dividing the serosa over the hilar vessels (Fig. 18.3). As you pass towards the upper pole of the spleen you will encounter the short gastric vessels. Divide these now with the harmonic scalpel. Alternatively, they can be divided together with the hilar vessels using a vascular stapler.

Fig. 18.3 Transection of hilar vessels.

4. A fan retractor may be used by the first assistant from the right upper quadrant position to retract the splenic flexure and, later in the procedure, to retract the stomach away from the spleen.

5. Once a clear view in front and behind the hilum is obtained, place a vascular stapler across the vessels at the hilum of the spleen and divide the splenic artery and vein. Take care to remain close to the spleen as straying medially may damage the tail of the pancreas.

6. A simple approach to the short gastric vessels is to include them in the vascular staple line or reload the stapler and divide them.

7. Once all the vessels are divided, lift the spleen anteriorly to allow division of any remaining posterior attachments using a harmonic scalpel. In cases of massive splenomegaly this manoeuvre may prove difficult, as there is limited room to lift the spleen.

8. At this stage only the superior attachments of the spleen remain. Insert a retrieval bag through the 12-mm port and slip it over the lower pole of the spleen. Divide the superior attachments to allow the spleen to fall into the retrieval bag.

9. Partially withdraw the bag through the 12-mm port and use a finger or sponge holding forceps through the port site to break down the spleen whilst it is still intra-abdominal. Remove the spleen piecemeal from the bag using a combination of sponge holding forceps and a sucker.

OPEN SPLENECTOMY

ACCESS

Action

1. Ligate the splenic artery at the beginning of the operation if the spleen is very large or prior to infusing platelets in patients with ITP. Enter the lesser sac by dividing 10 cm of the gastrocolic omentum using diathermy or a harmonic scalpel. Incise the peritoneum at the superior border of the pancreas to identify the tortuous splenic artery. Use a right angle forceps to pass a ligature behind the splenic artery and ligate it in continuity with a large non-absorbable suture.

2. Gently divide omental adhesions to the lower pole of the spleen using diathermy, harmonic scalpel or suture ligation. These adhesions are fragile and bleed easily.

3. Use your left hand to draw the spleen medially and have your assistant retract the abdominal wall laterally.

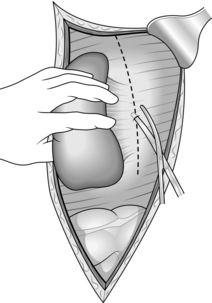

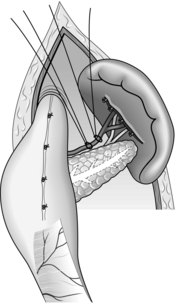

4. Using scissors, incise the peritoneum that attaches the spleen to the lateral sidewall (Fig. 18.4). Extend this incision up along the lateral border of the spleen towards the diaphragm. Because of its position this cannot always be achieved under direct vision. Extend this incision downwards around the lower pole of the spleen to identify the splenic flexure and separate it from the spleen.

5. Dividing this lateral attachment allows your left hand to gently move the spleen medially and upwards into the abdominal wound. As the spleen is lifted medially take care to identify and preserve the tail of the pancreas, which must be separated from the splenic hilum.

6. As the spleen becomes more mobile divide the adhesions from the upper pole of the spleen to the diaphragm.

7. Divide the peritoneum over the front of the splenic hilum from the lower pole to the upper pole. The stomach can be very close to the spleen at this point so take care not to damage the greater curve. The short gastric arteries are branches of the splenic artery that run to the fundus of the stomach in this region. Divide them carefully with the harmonic scalpel or by suture ligation (Fig. 18.5).

Fig. 18.5 Exposure of the splenic vessels after division of the gastrosplenic ligament and short gastrics.

8. At this stage the spleen should be fairly mobile and attached only by the vessels in the splenic hilum. These can be thinned by careful dissection. Divide the splenic vessels between large clips, such as a Roberts. Several clips may be required to take all the vessels. Be careful not to injure the tail of the pancreas at this point. Divide any remaining peritoneal attachments to remove the spleen.

CONSERVATIVE SPLENECTOMY

Appraise

1. Following splenectomy there is a 1–2% risk of developing overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI) from encapsulated bacteria, especially pneumococcus, usually within 2 years of operation. Leaving behind viable splenic tissue rather than total splenectomy may reduce this risk by preserving some of the spleen’s immunological function.

2. Increasingly, there is a move towards non-operative management of splenic trauma or conservative splenic surgery, particularly in children.

3. Anatomically, there are between three and seven well-defined splenic segments, each with an independent blood supply, which makes a partial splenectomy a practical proposition.

Assess

1. At operation for abdominal trauma, immediately remove a spleen that is either fragmented or avulsed from its vascular pedicle. Under these circumstances consider autotransplantation of splenic tissue by suturing a piece of omentum around a sliver of removed splenic pulp to encourage splenic regeneration (splenosis).

2. If the extent of the damage and bleeding is less severe, gently mobilize the spleen into the wound after dividing its peritoneal attachments. Remove attached clot and examine the organ thoroughly. Decide whether topical haemostatic agents, partial splenectomy or some form of splenic repair is feasible, with or without ligation of the splenic artery or its branches.

3. Capsular tears and other minor injuries can often be controlled by application of a haemostatic agent.

4. Marsupialization (Greek: maryp(p)ion = a pouch; removing the top) of a thin-walled congenital or traumatic cyst avoids splenectomy but there is a risk of recurrence.

Action

1. To avoid the need for splenectomy apply haemostatic applications to superficial lacerations of the capsule or splenic pulp. Full mobilization of the spleen is unnecessary if the damaged area is accessible, but use suction to obtain a clear view. Fibrin glue may be sprayed over the injured site or injected into a splenic laceration. Apply an appropriate disc of haemostatic sponge to the laceration and maintain light pressure until the sponge soaks up the blood and becomes adherent. Gently pack off the area and leave if for 5–10 minutes before checking that you have achieved haemostasis.

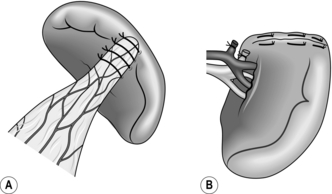

2. Deeper or more extensive lacerations may still be suitable for repair. Mobilize the spleen, at least in part. Use synthetic absorbable sutures on a long blunt needle. Take deep bites of splenic tissue on either side of the tear, and tie the sutures snugly. Use omentum or Teflon buttresses to prevent the stitches cutting through (Fig. 18.6A), together with a topical haemostatic agent to control surface bleeding. Alternatively, wrap the organ in an absorbable polyglycolate mesh and suture the edges of the mesh together to envelop the spleen.

3. For partial splenectomy, fully mobilize the organ and carefully dissect in the splenic hilum to identify and ligate the segmental arteries and veins. Incise the capsule of the spleen at the line of ischaemia and use a finger-fracture technique to resect the upper or lower pole (Fig. 18.6B). Secure haemostasis by means of synthetic absorbable sutures or with argon coagulation. Preserve at least 30% of the spleen volume to maintain adequate splenic function.

Aftercare

1. Check the haemoglobin, white cell and platelet counts postoperatively. Leucocytosis and thrombocythaemia nearly always ensue, with peaks at 7–14 days. Persistent leucocytosis and pyrexia suggest the possibility of a subphrenic abscess. Consider antiplatelet medication such as aspirin if the platelet count exceeds 1000 × 109 per litre.

2. After an emergency splenectomy, vaccinate the patient once fully recovered. Administer prophylactic antibiotics (cephalosporin based) at induction of anaesthesia. If you have previously overlooked it, start immunization with anti-pneumococcal vaccine. Children should receive prophylactic penicillin for 2 years to prevent post-splenectomy sepsis. Advise adults to take an antibiotic such as amoxicillin at the first sign of any infective illness.

3. Monitor the haemoglobin level and remove the drain, if used, when it ceases to function.

4. Immunological function after splenorrhaphy or partial splenectomy is uncertain, so prophylactic measures should probably be taken against post-splenectomy sepsis.

5. Nasogastric tube and drain is not routinely used after splenectomy. Remove the nasogastric tube if used when gastric aspirates diminish.

Complications

1. Haemorrhage: intra-operative haemorrhage can develop rapidly. Alert the anaesthetist that there is active bleeding. Small splenic tears may be controlled with compression by surrounding tissues and haemostatic diathermy. However, the spleen is an end organ and the quickest way to get control of a difficult situation is to mobilize the spleen and get control of the hilar vessels. In a laparoscopic splenectomy this may require rapid conversion to open surgery. Once the spleen has been mobilized onto the abdominal wall, a soft bowel clamp is applied across the splenic hilum. This will control the situation and allows the anaesthetist time to resuscitate the patient before completing the operation. When the patient is stabilized, the soft bowel clamp can be sequentially removed to ligate the hilar vessels and to make sure that the tail of the pancreas is not damaged.

2. Postoperative haemorrhage is reported to occur in 2–5% of patients after splenectomy. Postoperative bleeding is suspected if the patient becomes unstable or a drain, if used, produces a large amount of fresh blood. If the patient is stable, re-laparoscopy can be undertaken to look for the site of bleeding. The usual sites are the hilar or short gastric vessels. If identified, the bleeding vessel can be clipped or sutured. If the patient is unstable, urgent laparotomy is preferred to control the bleeding site.

3. Overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI): post-splenectomy sepsis remains the most severe cause of late postoperative morbidity and mortality. Following splenectomy there is a 1–2.5% risk of developing overwhelming septicaemia from encapsulated bacteria, usually within 2 years of operation. The risk is higher in young children (4–10%) and after splenectomy for haematological disease, but fatal cases have also been reported in adults. The mortality rate of post-splenectomy sepsis is higher in children (50%). Though long-term oral antibiotic prophylaxis is controversial, all patients should be thoroughly counselled to seek prompt medical attention, particularly for respiratory illness. Patients should be advised regarding immunization and foreign travel and to carry an information card at all times. All patients should be advised to have yearly influenza immunization.

4. Injury to adjacent organs: the splenic flexure of the colon, the greater curvature of the stomach and the tail of the pancreas are all susceptible to damage during splenectomy. Pancreatic injury following laparoscopic splenectomy resulting in pancreatitis and pancreatic fistula occurs in 1–3% of cases. Laparotomy may be required to inspect the damage. A colonic or stomach injury should be closed using interrupted seromuscular absorbable sutures. Injury to the tail of pancreas may require either primary repair or resection. Undetected pancreatic injury may later present as pancreatic ascites, a subphrenic collection or pancreatic fistula. All such injuries are rare.

5. Thrombocytosis can occur following splenectomy, leading to deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary emboli. Portal vein thrombosis has also been reported. It is a difficult diagnosis to make as symptoms are of vague abdominal pains. We recommend routine subcutaneous heparin prophylaxis and compression stockings in all patients.

6. Respiratory complications such as pneumonia, atelectasis, and pleural effusion are by far the most common morbidity following open splenectomy, occurring in 20–40% of patients. There are fewer respiratory complications after laparoscopic splenectomy with early mobilization and discharge on the second or third postoperative day. Chest infection may result from splinting of the left diaphragm causing atelectasis. Vigorous physiotherapy will help early recovery.

7. Subphrenic collection: this may develop due to minor bleeding or serous oozing from the raw area in the diaphragm and retroperitoneum. If this happens, carefully monitor the platelet count and clotting parameters. A CT (computed tomography) scan is often required to confirm the diagnosis. Subphrenic abscess has been reported in 4% of patients after open splenectomy for all indications in a large series. This complication is less common after laparoscopic splenectomy and in the absence of gastrointestinal trauma. A subphrenic collection can usually be drained percutaneously with antibiotic cover but may occasionally require a laparotomy.

8. Accessory spleens are noted in 15–30% of patients and account for late failure of splenectomy in ITP. The ability to identify accessory spleens using laparoscopic techniques is in question. The initial step during laparoscopic splenectomy is a systematic exploration for accessory splenic tissue. When identified, they are immediately removed because they may be easily lost during the dissection. Preoperative CT is performed by some units to identify these structures.

9. Other sporadic complications include trocar site hernias, wound infection and ileus.

Clarke, P.J., Morris, P.J. Surgery of the spleen. In: Morris P.J., Wood W.C., eds. Oxford Textbook of Surgery. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001:2755–2764.

Cooper, M.J., Williamson, R.C.N. Splenectomy: indications, hazards and alternatives. Br J Surg. 1983; 71:173–180.

Casaccia, M., Torelli, P., Pasa, A., et al. Putative predictive parameters for the outcome of laparoscopic splenectomy: a multicenter analysis performed on the Italian registry of laparoscopic surgery of the spleen. Ann Surg. 2010; 251(2):287–291.

Department of Health. Department of Health guidance for patients following splenectomy. Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/1135/82/04113582.pdf. Accessed 20/12/2012.

Grahn, S.W., Alvarez, J., Kirkwood, K. Trends in laparoscopic splenectomy for massive splenomegaly. Arch Surg. 2006; 141:755–762.

Habermalz, B., Sauerland, S., Decker, G., et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy: the clinical practice guidelines of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES). Surg Endosc. 2008; 22:821–848.

Kercher, K.W., Matthews, B.D., Walsh, R.M., et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy for massive splenomegaly. Am J Surg. 2002; 183:192–196.

Kojouri, K., Vesely, S.K., Terell, D.R., et al. Splenectomy for adult patients with idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura. Blood. 2004; 104:2623–2632.

Olmi, S., Scaini, A., Erba, L., et al. Use of fibrin glue (Tissucol) as a haemostatic in laparoscopic conservative treatment of spleen trauma. Surg Endosc. 2007; 21:2051–2054.

Park, A.E., Birgisson, G., Mastrangelo, M.J., et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy: outcomes and lessons learned from over 200 cases. Surgery. 2000; 128:660–667.

Pomp, A., Gagner, M., Salky, B., et al. Laparoscopic splenectomy: a selected retrospective review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005; 15:139–143.

Redmond, H.P., Redmond, J.M., Rooney, B.P., et al. Surgical anatomy of the human spleen. Br J Surg. 1989; 76:198–201.

Schwartz, J., Leber, M.D., Gillis, S., et al. Long term follow-up after splenectomy performed for immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). Am J Haematol. 2003; 72:94–98.

Uranues, S., Alimoglu, O. Laparoscopic surgery of the spleen. Surg Clin North Am. 2005; 85:75–90.

Velmahos, G.C., Zacharias, N., Emhoff, T., et al. Management of the most severely injured spleen. Arch Surg. 2010; 145:456–460.

Walsh, R.M., Brody, F., Brown, N. Laparoscopic splenectomy for lymphoproliferative disease. Surg Endosc. 2004; 18:272–275.

Winslow, E.R., Brunt, L.M. Perioperative outcomes of laparoscopic versus open splenectomy: a meta-analysis with an emphasis on complications. Surgery. 2003; 134:647–655.