Chapter 51 Spinal Traction

(Includes Mechanical and Inversion Traction) (Excludes Manual Traction)

OVERVIEW.

The proposed mechanisms for traction include (1) gating out pain transmissions, (2) interrupting the pain-spasm cycle, (3) reducing pressure on pain-sensitive structures (reducing the disc’s bulge that compresses a nerve root), and (4) increasing the size of the foramen opening.1

Traction can be administered mechanically (using an electric motor), manually (using hands), and positionally. Mechanical traction devices typically include an electric motor, a cable, and a harness or device that is secured to the patient’s body. Inversion traction is a special case of positional traction whereby individuals use their own body weight (often hanging upside-down from boots) to exert traction forces on the low back. This section will report on spinal traction applied mechanically or through inversion.1

SUMMARY: CONTRAINDICATIONS AND PRECAUTIONS.

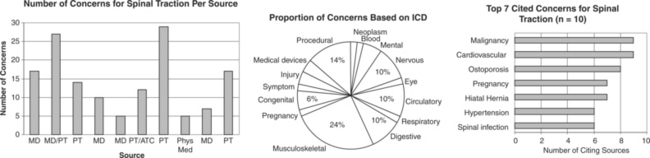

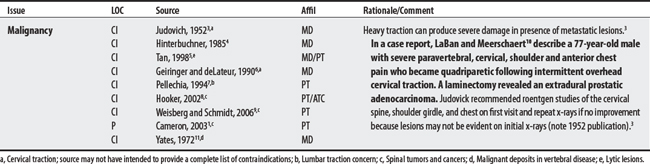

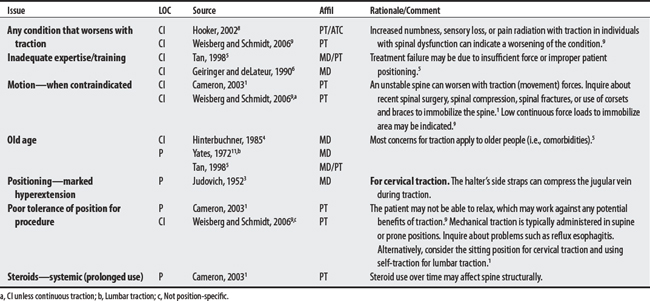

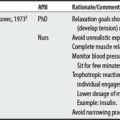

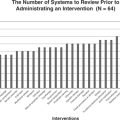

Ten sources cited a total of 51 concerns for spinal traction. Approximately 40 and 43 concerns are relevant to lumbar and cervical traction, respectively. Concerns ranged from 5 to 29 per source, with a physical therapist citing the greatest number. The largest proportion of concerns was musculoskeletal (24%). Whereas digestive (i.e., hernia, hemorrhoids, peptic ulcer) and respiratory concerns were particular to lumbar traction, TMJ, denture, and C1-C2 stability issues were particular to cervical traction. Overall, the most frequently cited concerns were malignancy, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis.

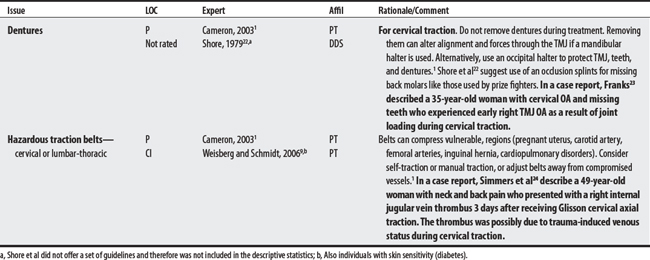

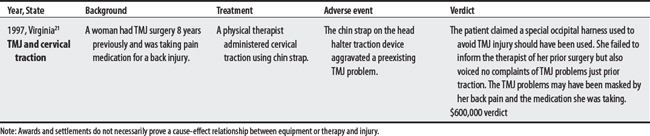

OTHER ISSUES.

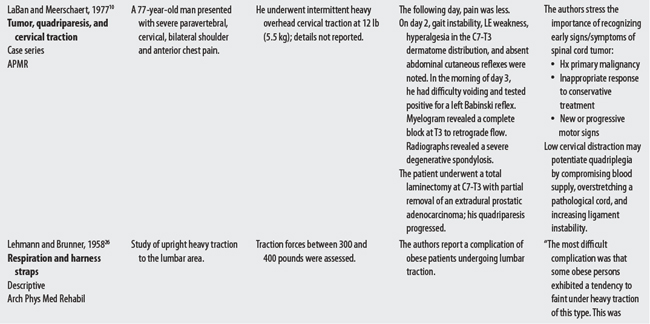

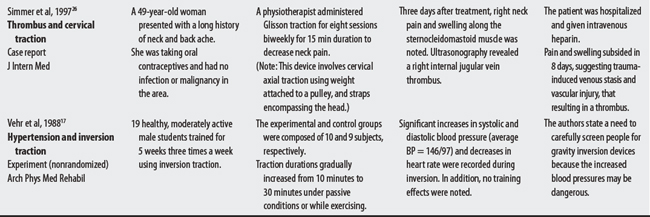

The FDA2 received nine reports of mechanical traction malfunctioning between February 1985 and July 2000 that allegedly have resulted in soft tissue injury, including increased symptoms, pain, and contusions. The devices exceeded the load setting, released cord tension unexpectedly, or fell from an unsecured position.

CONTRAINDICATIONS AND PRECAUTIONS FOR TRACTION

D50-D89 DISEASES OF BLOOD AND BLOOD-FORMING ORGANS, AND CERTAIN DISORDERS

F00-F99 MENTAL AND BEHAVIORAL DISORDERS

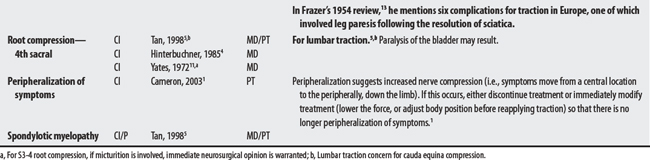

G00-G99 DISEASES OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

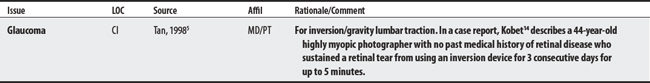

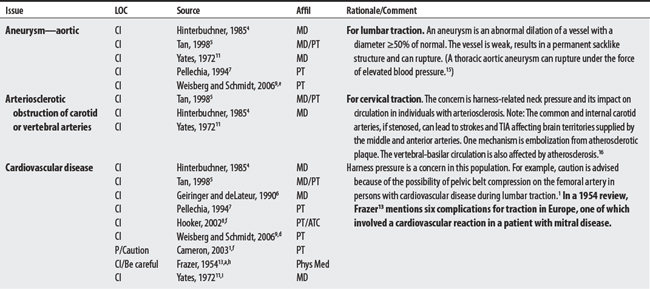

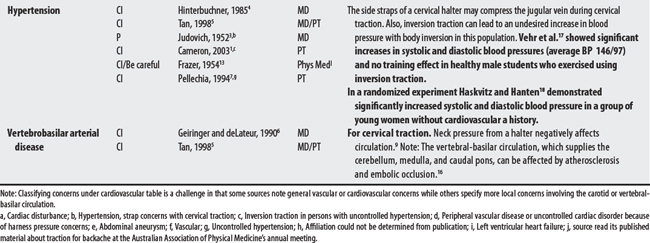

I00-I99 DISEASES OF THE CIRCULATORY SYSTEM

J00-J99 DISEASES OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

K00-K93 DISEASES OF THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM

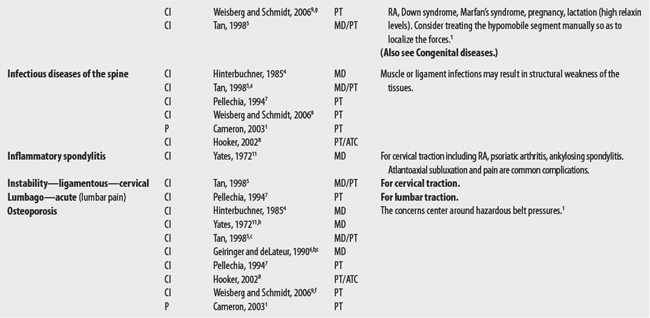

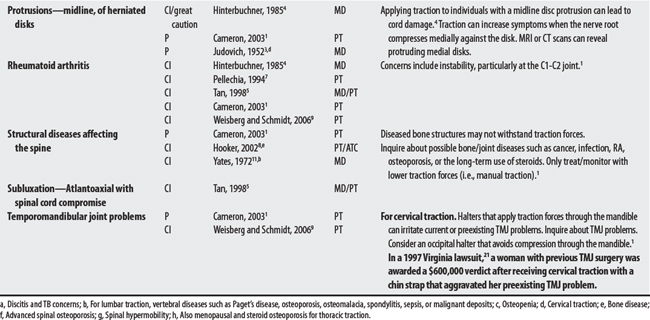

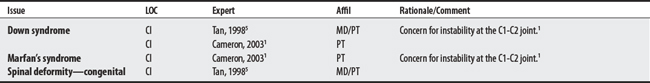

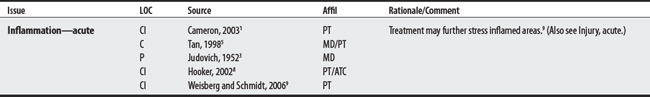

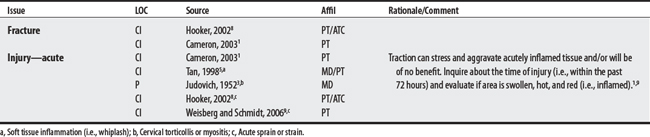

M00-M99 DISEASES OF THE MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE

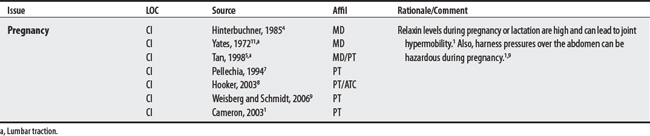

O00-O99 PREGNANCY, CHILDBIRTH, AND PUERPERIUM

R00-R99 SYMPTOMS, SIGNS, AND ABNORMAL CLINICAL AND LABORATORY FINDINGS (NOT ELSEWHERE CLASSIFIED)

S00-T98 INJURY, POISONING, AND CERTAIN OTHER CONSEQUENCES OF EXTERNAL CAUSES

1 Cameron MH. Physical agents in rehabilitation: from research to practice. St Louis: Saunders, 2003.

2 U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Web page Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cdrh/mdr/. Accessed: November 7, 2005

3 Judovich BD. Herniated cervical disc; a new form of traction therapy. Am J Surg. 1952;84:646.

4 Hinterbuchner C. Traction. In Basmajian JV, editor: Manipulation, traction, and massage, ed 3, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1995.

5 Tan JC. Practical manual of physical medicine and rehabilitation: diagnostics, therapeutics, and basic problems. St Louis: Mosby, 1998.

6 Geiringer SR, deLateur BJ. Physiatric therapeutics 3. Traction, manipulation, and massage. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71(4-S):S264-S266.

7 Pellechia GL. Lumbar traction: a review of the literature. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;20(5):262-267.

8 Hooker DN. Spinal traction. In Prentice WE, editor: Therapeutic modalities for physical therapists, ed 2, New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002.

9 Weisberg J, Schmidt TA. Spinal traction. In: Hecox B, Mehreteab TA, Weisberg J, editors. Integrating physical agents in rehabilitation. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006.

10 LaBan MM, Meerschaert JR. Quadriplegia following cervical traction in patients with occult epidural prostatic metastasis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1975;56(10):455-458.

11 Yates DAH. Indications and contra-indications for spinal traction. Physiotherapy. 1972;58(2):55-57.

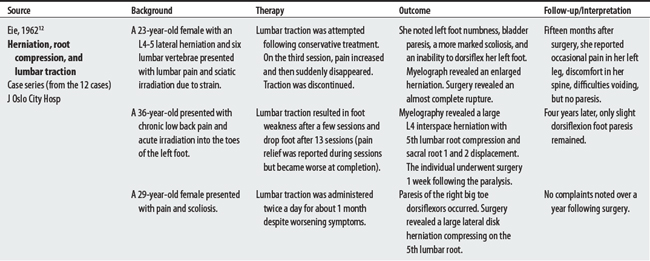

12 Eie N. Complications and hazards of traction in the treatment of ruptured lumbar intervertebral disks. J Oslo City Hosp Board. 1962;12:5-12.

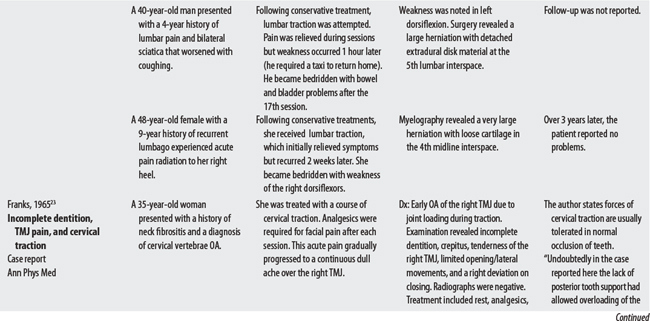

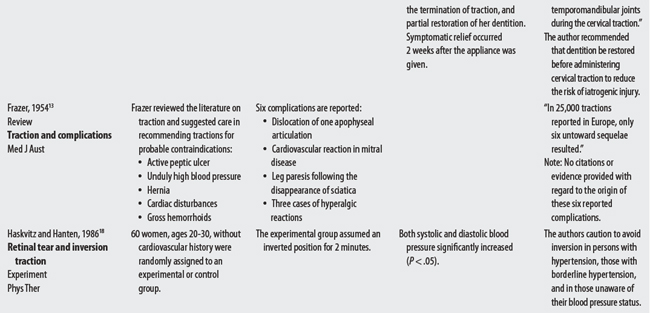

13 Frazer EH. The use of traction in backache. Med J Aust. 1954;41:694-697.

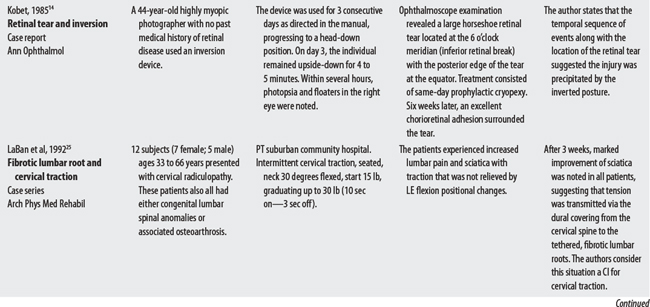

14 Kobet KA. Retinal tear associated with gravity boot. Ann Ophthalmol. 1985;17(5):308-310.

15 Goodman CC. The cardiovascular system. In Goodman CC, Boissonnault WG, Fuller KS, editors: Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 2, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2003.

16 Jensen FE. Cerebrovascular disease. In Loscalzo J, Creager MA, Dzau VJ, editors: Vascular medicine: a textbook of vascular biology and diseases, ed 2, Boston: Little, Brown, 1996.

17 Vehr PR, Plowman SA, Fernhall B. Exercise during gravity inversion: acute and chronic effects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69(11):950-954.

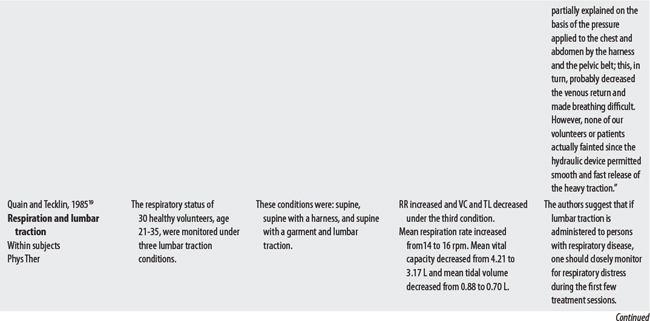

18 Haskvitz EM, Hanten WP. Blood pressure response to inversion traction. Phys Ther. 1986;66:1361-1364.

19 Quain MB, Tecklin JS. Lumbar traction. Its effect on respiration. Phys Ther. 1985;65:1343-1346.

20 Goodman CC. The gastrointestinal system. In Goodman CC, Boissonnault WG, Fuller KS, editors: Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 2, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2003.

21 Medical malpractice verdicts, settlements, and experts, November 1997, p 41, loc 1.

22 Shore NA, Schaefer MG, Hoppenfeld S. Iatrogenic TMJ difficulty: cervical traction may be the etiology. J Prosthet Dent. 1979;41(5):541-542.

23 Franks AST. Temporomandibular joint dysfunction associated with cervical traction. Ann Phys Med. 1965;8(1):38-40.

24 Simmers TA, Bekkenk MW, Vidakovic-Vukic M. Internal jugular vein thrombosis after cervical traction. J Intern Med. 1997;241(4):333-335.

25 LaBan MM, Macy JA, Meerschaert JR. Intermittent cervical traction: a progenitor of lumbar radicular pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73:295-296.

26 Lehmann JF, Brunner GD. A device for the application of heavy lumbar traction: its mechanical effects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1958;39(11):696-700.