Chapter 16 Spinal Orthoses

History of Spinal Orthotic Management

The first evidence of the use of spinal orthoses can be traced back to Galen (c.131 to 201 AD). Primitive orthotic devices were made of items that were readily available during this period (Figure 16-1). These items consisted of leather, whalebone, and tree bark. Spinal orthoses, although crude in their construction, have been recovered by archaeologists from the cliff dwellings of pre-Columbian Indians. The word orthosis is Greek and means “to make straight.”2 Ambroise Paré (1510 to 1590) wrote about bracing and spinal supports, and Nicholas Andry (1658 to 1742) coined the term orthopaedia, pertaining to the straightening of children.4 Unstable areas such as fractures were often held in a corrected position with an orthosis, to allow for healing to occur. Normally fixed deformities were accommodated while flexible deformities were corrected. Orthopaedia was the predecessor to the field of orthotics.1

The primary goal of modern orthoses is to aid a weakened muscle group or correct a deformed body part. The orthosis can protect a body part to prevent further injury, or can correct the position (immediate term or long-term) of the body part. The same approach is true for spinal orthoses. The clinician’s priority should be to determine which spinal motion to control. Good clinical outcomes can be maximized through the proper selection, use, and application of the orthosis. (See Chapters 14 and 15 for further information on orthoses.)

Terminology

Prefabricated Versus Custom Orthoses

The availability of prefabricated orthoses today presents the rehabilitation team with a variety of choices and some challenges. Many of the prefabricated orthoses come in various sizes and can be fitted to patients often with little or no adjustment. While this can be a benefit to the patient and the team in terms of time, care should be taken to ensure that the design and function of these orthoses are appropriate for the patient’s condition and not used purely for convenience. Custom orthoses, in most cases, provide a more comfortable fit with a higher degree of control, and can be designed to accommodate a patient’s unique body shape or deformities. Recognition of the time needed to fabricate the orthosis, the experience of the fabricator, the patient’s specific condition, and the expectations of the patient are all factors that should be considered when ordering a custom orthosis.

Spinal Anatomy

The vertebral column is composed of 33 vertebrae, including 7 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, 5 inferiorly fused vertebrae that form the sacrum, and 5 coccygeal. The spinal column not only bears the weight of the body, but it also allows motion between body parts and serves to protect the spinal cord from injury. Before birth, there is a single C-shaped concave curve anteriorly. At birth, infants have only a small angle at the lumbosacral junction. As a child learns to stand and walk, lordotic curves develop in the cervical and lumbar region (age 2 years). These changes can be attributed to the increase in weight-bearing and differences in the depth of the anterior and posterior regions of the vertebrae and disks.28,32

The spine is composed of more than vertebral bodies. The intervertebral disk is composed of a nucleus pulposus, annulus fibrosus, and cartilaginous end plate. Disks make up approximately one third of the entire height of the vertebral column. The nucleus contains a matrix of collagen fibers, mucoprotein, and mucopolysaccharides. They have hydrophilic properties, with a very high water content (90%) that decreases with age.27 The nucleus is centrally located in the cervical thoracic spine, but more posteriorly located in the lumbar spine. The annulus fibrosus has bands of fibrous laminated tissue in concentric directions, and the vertebral end plate is composed of hyaline cartilage.

Normal Spine Biomechanics

Movement of the vertebral column occurs as a combination of small movements between vertebrae. The mobility occurs between the cartilaginous joints at the vertebral bodies and between the articular facets on the vertebral arches. Range of motion is determined by muscle location, tendon insertion, ligamentous limitations, and bony prominences. In the cervical region, axial rotation occurs at the specialized atlantoaxial joint. At the lower cervical levels, flexion, extension, and lateral flexion occur freely. In these areas, however, the articular processes, which face anteriorly or posteriorly, limit rotation. In the thoracic region, movement in all planes is possible, although to a lesser degree. In the lumbar region, flexion, extension, and lateral flexion occur, but rotation is limited because of the inwardly facing articular facets.11 An understanding of the three-column concept of spine stability/instability is helpful to ensure that the proper orthosis is prescribed. The anterior column consists of the anterior longitudinal ligament, annulus fibrosus, and the anterior half of the vertebral body. The middle column consists of the posterior longitudinal ligament, annulus fibrosus and the posterior half of the vertebral body. The posterior column consists of the interspinous and supraspinous ligaments, the facet joints, lamina, pedicles, and the spinous processes. The loss of normal spinal anatomy can affect the stability of the spine.

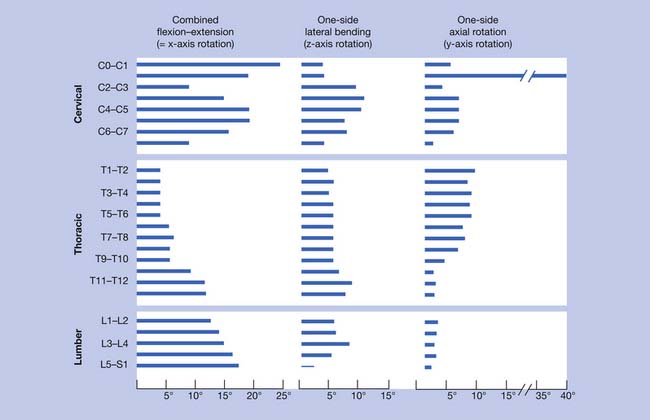

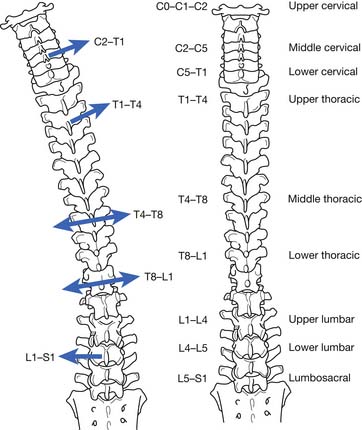

Spine motion can be classified with reference to the horizontal, frontal, and sagittal planes. Spinal motion can shift the center of gravity, which is normally located approximately 2 to 3 cm anterior to the S1 vertebral body. White and Panjabi33 provided a summary of the current literature, revealing motion in flexion and extension, laterally, and axially (Figure 16-2). In the cervical spine, extension occurs predominantly at the occipital C1 junction. Lateral bending occurs mainly at the C3–C4 and C4–C5 levels. Axial rotation occurs mostly at the C1–C2 levels. In the thoracic spine, flexion and extension occur primarily at the T11–T12 and T12–L1 levels. Lateral bending is fairly evenly distributed throughout the thoracic levels. Axial rotation occurs mostly at the T1–T2 level, with a gradual decrease toward the lumbar spine. The thoracic spine is the least mobile because of the restrictive nature of the rib cage. In the lumbar spinal segment, movement in the sagittal plane occurs more at the distal segment, with lateral bending predominantly at the L3–L4 level. There is insignificant axial rotation in the lumbar spinal segment.

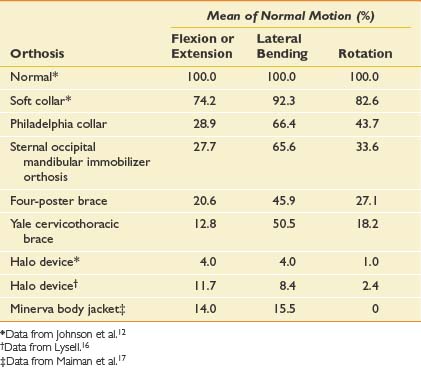

Knowledge of the normal spinal range of motion helps in understanding how the various cervical orthoses can limit that range (Table 16-1). Soft collars provide very little restriction in any plane. The Philadelphia-type collar mostly limits flexion and extension. The four-poster brace and Yale orthosis have better restriction, especially with flexion-extension and rotation. The halo brace and Minerva body jacket have the most restriction in all planes of motion.

Table 16-1 Normal Cervical Motion From Occiput to First Thoracic Vertebra and the Effects of Cervical Orthoses

An interesting phenomenon related to movement in the spine occurs during motion. If the movement along one axis is consistently associated with movement around another axis, coupling is occurring. For example, if a patient performs left lateral movement (frontal plane) motion, the middle and lower cervical and upper thoracic spine rotate to the left in the axial plane (Figure 16-3). This causes the spinous processes (posterior side of the body) to move to the right. In the lower thoracic spinal segment, left lateral movement in the frontal plane can cause rotation in the axial plane, with the spinal processes moving in either direction. The lumbar area has a contradictory movement pattern when compared with the cervical spine. With left lateral bending of the lumbar spine, the spinous processes move to the left. A three-dimensional perspective is important to maintain during examination. Patients with scoliosis and patients who undergo radiologic testing would benefit from an evaluation for the normal coupling patterns noted.

Nachemson21–23 performed the classic studies on normal adults that measured intradiskal pressures during a variety of activities and positions. Standing pressure was referenced as 100 in the lumbar disk. Lowest pressure measurements were noted in the supine position, with progressively higher pressures in the following positions: side lying, standing, sitting, standing with hip flexion, sitting with forward flexion, standing with forward flexion, and lifting a load while sitting with forward flexion.24

Description of Orthoses

Head Cervicothoracic Orthoses

Type: Halo Orthosis

Biomechanics

The halo orthosis (Figure 16-4) provides flexion, extension, and rotational control of the cervical region. Pressure systems are used for control of motion, as well as to provide slight distraction for immobilization of the cervical spine.

Design and Fabrication

This orthosis provides maximum restriction in motion of all the cervical orthoses. It is the most stable orthosis, especially in the superior cervical spine segment. A halo is used for approximately 3 months (10 to 12 weeks) to ensure healing of a fracture or of a spinal fusion. Usually a cervical collar is indicated after the halo is removed, because the muscles and ligaments supporting the head become weak after disuse. All pins on the halo ring should be checked to ensure tightness 24 to 48 hours after application, and retorqued if necessary.

Cervical Orthoses

Type: Philadelphia or Miami J

Biomechanics

The Philadelphia (Figure 16-5) and Miami J (Figure 16-6) orthoses provide some control of flexion, extension, and lateral bending, and minimal rotational control of the cervical region. Pressure systems are used for control of motion, as well as to provide slight distraction for immobilization of the cervical spine. Circumferential pressure is also intended to provide warmth and as a kinesthetic reminder for the patient.

Cervicothoracic Orthoses

Type: Sternal Occipital Mandibular Immobilizer

Biomechanics

The sternal occipital mandibular immobilizer (SOMI; Figure 16-7) provides control of flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation of the cervical spine. Pressure systems are used for control of motion, as well as to provide slight distraction for immobilization of the spine. A benefit of the SOMI orthosis is that it can be donned while the patient is in the supine position. The SOMI is a good choice for patients who are restricted to bed, because there are no posterior rods to interfere with comfort of the patient. A headband can be added so that the chin piece can be removed. This maintains stability but improves accessibility for daily hygiene and eating.

Cervicothoracolumbosacral Orthoses

Thoracolumbosacral Orthoses

Type: Thoracolumbosacral Orthosis (Prefabricated)

Biomechanics

The thoracolumbosacral orthosis (TLSO; prefabricated) (Figure 16-8) provides control of flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation using three-point pressure systems and circumferential compression.

Type: Thoracolumbosacral Orthosis (Custom-Fabricated Body Jacket)

Biomechanics

The body jacket (Figure 16-9) provides control of flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation. It uses three-point pressure systems and circumferential compression.

Type: Cruciform Anterior Spinal Hyperextension Thoracolumbosacral Orthosis

Biomechanics

The cruciform anterior spinal hyperextension (CASH) TLSO (Figure 16-10) provides flexion control for the lower thoracic and lumbar regions. It accomplishes this by way of a three-point pressure system. The system consists of posteriorly directed forces through a sternal and suprapubic pad, and an anteriorly directed force applied through a thoracolumbar pad attached to a strap that extends to the horizontal anterior bar.

Type: Jewett Hyperextension Thoracolumbosacral Orthosis

Biomechanics

The Jewett hyperextension TLSO (Figure 16-11) provides flexion control for the lower thoracic and lumbar regions. This is done with a three-point pressure system consisting of posteriorly directed forces through a sternal and suprapubic pad, and an anteriorly directed force applied through a thoracolumbar pad attached to a strap that extends to the lateral uprights.

Lumbosacral Orthoses

Type: Lumbosacral Corset

Biomechanics

The lumbosacral corset (Figure 16-12) provides anterior and lateral trunk containment, and assists in the elevation of intraabdominal pressure. Restriction of flexion and extension can be achieved with the addition of steel stays posteriorly.

Indications

This orthosis is the most frequently prescribed support for patients with low back pain.29 It has been used for herniated disks and lumbar muscle strain, and to control gross trunk motion for pain control after single-column compression fractures with one-third or less anterior height loss.34

Special Considerations

Long-term use of a lumbosacral corset can cause an increase in motion in the segments above or below the area controlled by the orthosis.26 Muscle atrophy can also potentially occur after long-term use, causing an increased risk of reinjury. Patients can also develop a psychologic dependence on the support after injury.15

Type: Lumbosacral Chair-Back Orthoses

Biomechanics

This brace (Figure 16-13) provides limitation of flexion, extension, and lateral flexion. It also provides elevation of intraabdominal pressure.

Sacroiliac Orthoses

Type: Sacroiliac Orthosis or Sacral Orthosis

Design and Fabrication

This orthosis is usually made from cloth that wraps around the pelvis and hips. Some models also include laces on the side in which adjustments can be made, whereas others use straps for adjusting. Closure can be with hook and loop (Velcro) or hook and eye fasteners or snaps. Many different styles are available in prefabricated sizes, usually in 2-inch increments, and are designed to fit the circumference of the body at the level of the hips. The orthosis can be adjusted for body type and proper fit by taking tucks in the cloth, as needed. Custom orthoses can be fabricated based on careful measurements of the individual patient.

Scoliosis

Idiopathic (infantile, juvenile, adolescent), congenital, and neuromuscular scoliosis have different etiologies, treatment approaches, and outcomes. Idiopathic scoliosis is the most common form.30 Idiopathic infantile scoliosis is typically described from birth to 3 years of age, juvenile is from 4 years until the onset of puberty, and the adolescent type from puberty to closure of the facets.

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis is the most common type for which an orthosis is indicated, usually for curves between 25 and 45 degrees. Curves with an apex at T9 or lower can be managed with a TLSO. Curves with a higher apex require a Milwaukee brace. Single lumbar curves are treated with a lumbosacral orthosis.8

Congenital scoliosis is secondary to a vertebral anomaly that is present at birth. Failure of part of the vertebrae to form (e.g., hemivertebrae) or failure of the vertebrae to properly segment (block vertebrae), or a combination of both, can occur. Congenital scoliosis is associated with abnormal development in the embryo, and associated developmental abnormalities in other organ systems should be considered, especially in the renal, urinary, and cardiac systems.19

Neuromuscular diseases are also associated with scoliosis. The prevalence of scoliosis in this population is much higher than with idiopathic scoliosis, from 25% to 100%. In pediatric patients with a spinal cord injury, almost 100% have scoliosis. In general, there is a significant chance of progression in the presence of severe neurologic disease. In adults, however, scoliosis curvatures tend to be relatively benign and of the C-type appearance, and are less likely to progress to the extent that they cause clinical cardiopulmonary problems. Progression of the curve can occur in adulthood, which is typical for scoliosis in general. Spasticity or flaccidity can be present, depending on whether there is upper versus lower motor neuron involvement. Multisystem involvement is more common in this group because these diseases are not isolated to the spinal column. Consideration should also be made for the presence of contractures, hip dislocations, sensory abnormalities, mental retardation, and pressure ulcers.14

Scoliosis can continue to progress despite the proper use of an orthosis, and in these cases appropriate surgical referrals should be made. An important factor to consider before surgery is the pulmonary function in a patient with neuromuscular disease. Before surgery is considered, the forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in 1 second should be at least 40% of that predicted for the patient’s age. Fusions are delayed as long as possible in an attempt to achieve maximal spinal growth (>10 years of age). Declining pulmonary function, however, is a consideration for performing surgery earlier.20

Duval-Beaupere7 followed the long-term progression of idiopathic scoliosis and noted that curve progression accelerated during growth spurts. He noted that the younger the child, the higher the risk of curve progression, because of a greater amount of growth that remained. It has also been shown that the greater the curve, the more likely the curve would increase.14 Curves measured from 5 to 29 degrees, and the curves from 20 to 29 degrees progressed in almost 100% of the patients. Approximately 50% of the curves from 5 to 19 degrees appeared to progress.

Curve progression has been explained using Euler’s theory of elastic buckling of a slender column.31 Axial compressive forces evidently cause a column to buckle. This is associated with height growth and weight gain, especially increased upper limb weight during growth spurts. An increase in height and weight commonly occur together and might synergistically promote curve progression. It has been noted by these authors and others that the condition of a child with a large curve is more likely to progress than that of a child with a small curve.

The timing for surgery in a child with scoliosis is controversial. A child with a curve greater than 45 degrees, a child who is still growing, or a child who cannot or does not wear a brace are at a greater risk of curve progression and may be considered for surgery.

Type: Thoracolumbosacral Low-Profile Scoliosis Orthoses

Boston Brace, Miami Orthosis, Wilmington Brace

Biomechanics

The TLSO low-profile scoliosis orthoses (Figure 16-14) provide dynamic action using three principles (end-point control, transverse loading, and curve correction) to prevent curve progression and to stabilize the spine.

Design and Fabrication

The use of orthoses or other devices to halt the curve progression of structural scoliosis has been reported as far back as Hippocrates.18 Many different types of orthoses have been described in the literature. The one that stands out as being the most successful is the Milwaukee orthosis, which was described previously.

The effective nonoperative treatment of idiopathic scoliosis using a low-profile TLSO has been demonstrated over the past 30 years. The most common of these orthoses is the Boston brace, introduced by Hall and Miller10 in 1975.3 This system is available in prefabricated modules that are available in 30 sizes and can be ordered by measurement; they are then custom-fit to the patient. Modules can be used to fit approximately 85% of patients. Six of these sizes will fit approximately 60% of patients requiring an orthosis.9 The orthosis can also be custom-fabricated from a mold of the patient’s body. Trim lines are established based on the patient’s curve; they are designed to provide pressure in specified areas to maximize corrective forces, and at the same time be less visible under the patient’s clothing.

Indications

This orthosis is indicated in patients with an immature skeleton and documented progression of a thoracic or thoracolumbar idiopathic scoliosis that measures 25 to 35 degrees (measured by the Cobb method) and has an apex of T7 or lower.5

Contraindications

The orthosis is contraindicated in patients with curves that measure greater than 40 degrees and who are skeletally immature, or with curves in excess of 50 degrees after the end of growth. Both of these types of patients are typically candidates for surgery.6

Future Technology

Computer-Aided Design and Computer-Aided Manufacturing

Technology is available to help the practitioner improve efficiency in design and fabrication, as well as reducing the invasiveness of orthotic measurement of the patients. The development of computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) has allowed the fabrication of orthoses today in less time than it took only a few years ago. The BioScanner Biosculptor is one of the CAD-CAM systems available (Figure 16-15). (BioScanner biosculptor information is available online at http://www.biosculptor.com.) It combines CAD, laser scanning, three-dimensional imagery, and motion-tracking technology to design orthotic and prosthetic devices. This is an alternative to traditional casting methods. The body part involved is scanned via a handheld scanning wand, which uses a motion-tracking device embedded in the scanner. The wand is passed over the body part. A three-dimensional image of the body part is transmitted to the computer, and the software interprets the data. Any portion of the body can be directly scanned. There is no size limitation. A miniature transmitter is placed on the body to accommodate for any movement. The BioScanner is able to image negative and positive models, allowing the clinician to use the clinical techniques required for each patient. With scan-through-glass technology that the company provides for use with its scanner, the clinician can position the body horizontally for a TLSO. The BioScanner automatically corrects the refraction. The precision of the BioScanner captures shapes to an accuracy of 0.178 mm. It provides the clinician with detailed and accurate three-dimensional measurements. Patients can be scanned for spinal jackets without movement from supine to prone positions. An option in the computer software allows one hemisphere to be scanned, and then the computer develops the other hemisphere to form a complete image. The older plaster cast methods are becoming obsolete because of the following advantages of the scanning system: it is not messy, can be done quickly, minimizes pain for the patient, and is more accurate. Modifications to these scanned computerized models can then be made before fabrication of the device begins.

Bone Stimulation

The CMF SpinaLogic bone growth stimulator is a portable, battery-powered, microcontrolled, noninvasive bone growth stimulator indicated for adjunct electromagnetic treatment to primary lumbar spinal fusion surgery for one or two levels (Figure 16-16). (Information about the CMF SpinaLogic is available at the website of DJO, Inc: http://www.djortho.com.)

1. Andry N. Orthopaedia [facsimile reproduction of the first edition in English, London, 1743]. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1961.

2. [Anonymous]. Dorland’s medical dictionary, ed 24,. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1989.

3. Boston Brace International. Available at: http://www.bostonbrace.com. Accessed June 15, 2010.

4. Bunch W.H., Keagy R. Principles of orthotic treatment. St Louis: Mosby; 1975.

5. Carr W.A., Moe J.H., Winter R.B., et al. Treatment of idiopathic scoliosis in the Milwaukee brace: long term results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:599-612.

6. Cassella M.C., Hall J.E. Current treatment approaches in the nonoperative and operative management of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Phys Ther. 1991;71:897-909.

7. Duval-Beaupere G. Pathogenic relationship between scoliosis and growth. In: Zorab B.A., editor. Proceedings of the Third Symposiums on Scoliosis and Growth. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1971.

8. Fisher S.V., Winter R.B. Spinal orthosis in rehabilitation. In: Braddom R.L., editor. Physical medicine and rehabilitation. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1996.

9. Hall J.E., Miller M.E., Cassella M.C., et al. Manual for the Boston brace workshop. Boston: Children’s Hospital; 1976.

10. Hall J.E., Miller W., Shuman W., et al. A refined concept in the orthotic management of idiopathic scoliosis. Prosthet Orthot Int. 1975;29:7-13.

11. Hall-Craggs E.C.B. The back and spinal cord. In: Tyler N.C., editor. Anatomy as a basis for clinical medicine. Baltimore: Urban and Schwarzenberg, 1985.

12. Johnson R.M., Hart D.L., Simmons E.F., et al. Cervical orthoses: a study comparing their effectiveness in restricting cervical motion in normal subjects. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977;59:332.

13. Lonstein J.E. Orthoses for spinal deformities. In Goldberg B., Hsu J.D., editors: Atlas of Orthotics: biomechanical principles and application, ed 2, St Louis: Mosby–Year Book, 1985.

14. Lonstein J.E., Carlson M. The prediction of curve progression in untreated idiopathic scoliosis during growth. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:1061-1071.

15. Luskin R., Berger N. Atlas of orthotics: biomechanical principles and application: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. St Louis: Mosby; 1975.

16. Lysell E. Motion in the cervical spine, thesis. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1969:123.

17. Maiman D., Millington P., Novak S., et al. The effects of the thermoplastic Minerva body jacket on cervical spine motion. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:363-368.

18. Moe J.H., Bradford D.S., Winter R.B., et al. Scoliosis and other spinal deformities. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1978.

19. Monstein J.K.E. Orthosis for spinal deformities. In Goldberg B., Hsu J.D., editors: Atlas of orthoses and assistive devices, ed 3, St Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1997.

20. Murphy K.P., Steele B.M. Musculoskeletal conditions and trauma in children. In Molnar D.E., Alexander M.A., editors: Pediatric rehabilitation, ed 3, Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus, 1999.

21. Nachemson A.L. The influence of spinal movement on the lumbar intradiscal pressure and on the tensile stresses in the annulus fibrosus. Acta Orthop Scand. 1963;33:183.

22. Nachemson A.L. In vivo discometry in lumbar discs with irregular radiograms. Acta Orthop Scand. 1965;36:418.

23. Nachemson AL. A critical look at the treatment for low back pain: the research status of spinal manipulative therapy. DHEW publication no. (NIH) 76-998:21B. Bethesda, MD, 1975, DHEW.

24. Nachemson A.L. The lumbar spine: an orthopedic challenge. Spine. 1976;1:59-71.

25. Nachemson A.L. Orthotic treatment for injuries and diseases of the spinal column. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N A. 1987;1:22-24.

26. Norton P., Brown T. The immobilization efficiency of back braces: the effect on the posture and motion of the lumbosacral spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1957;39(1):111-139.

27. Panagiotacopulos N.D., Pope M.H., Bloch R., et al. Water content in human intervertebral discs: part II. Viscoelastic behavior. Spine. 1987;12:918.

28. Panjabi M.M., Takata K., Goel V., et al. Thoracic human vertebrae, quantitative three-dimensional anatomy. Spine. 1991;16:888-901.

29. Perry J. The use of external support in the treatment of low back pain. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52:1440-1442.

30. Tachdejian M.O. Pediatric orthopedics, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1990.

31. Timoshenko S., Gere J. Theory of elastic stability, ed 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1961.

32. Wambolt A., Spencer D.L. A segmental analysis of the distribution of lumbar lordosis in the normal spine. Orthop Trans. 1987;11:92-93.

33. White A.A., Panjabi M.M. The lumber spine. In White A.A., Panjabi M.M., editors: Clinical biomechanics of the spine, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1990.

34. White A.A., Panjabi M.M., White A.A., Panjabi M.M., editors. Clinical biomechanics of the spine, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1990.