Chapter 28. Spinal injuries

Spinal cord injury may be either complete (i.e. with no motor or sensory function below the level of injury) or incomplete (with partial preservation of sensory or motor function, or both). In 50% of cases of spinal injury there are associated injuries which also may require their own urgent management. As with head injuries the aim is to avoid exacerbating the primary injury.

Three elements contribute to spinal cord injury:

• Biomechanical movement

• Hypoxia due to A or B problems

• Underperfusion – C problems.

Causes of spinal cord injury

The principal causes of spinal cord injury are:

• Motor vehicle collisions

• Falls

• Sports:

Gymnastics and trampolining

Rugby football

Horse riding and hunting (female to male 5:1)

Skiing

Hang gliding

• Aquatic injuries, e.g. diving into shallow water

• Weight falling on the back.

Diagnosis

Signs and symptoms of spinal injury include:

• Pain (highly suggestive of bony injury)

• Tenderness

|

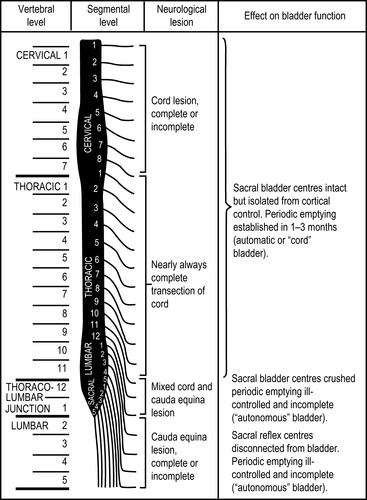

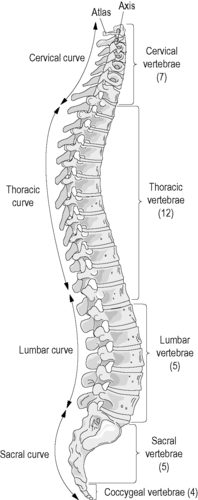

| Figure 28.1. |

| The spinal column. |

• Swelling

• Bruising (rare and usually late)

• Irregularity in the spine on palpation (a ‘step’) – occurs in only 10% of cases).

Sensory disturbances from spinal cord injury are even wider in their spectrum:

• ‘Pins and needles’ (paraesthesia)

• Electric shock-like pain at the moment of impact with no other indicator that injury has taken place

• Disturbances of proprioception, where the patient feels he or she is still in the same position as at the moment of impact, despite clearly now lying in another

• Burning pains through both arms or both lower limbs.

Burning pains in the upper limb are seen in motor vehicle deceleration accidents. In the lower limbs, burning pains are associated with ‘hyperpathia’ (touch registers as pain), seen most frequently in conus injuries.

Minor degrees of sensory or motor loss are frequently described by patients either in terms of ‘clumsiness’, ‘stiffness’ or ‘heaviness’ and such complaints must always be treated seriously.

Patients who have congenitally abnormal spines or diseases such as ankylosing spondylitis or rheumatoid arthritis do not require the same degree of force to produce a cord injury as those with a normal spine.

Assessment

• Any patient who is unconscious as a result of a head injury (or who could have had a head injury in association with unconsciousness) and any victim of trauma who is unable to give an account of the accident (e.g. through intoxication) must be regarded as having a spinal cord injury until proved otherwise

• It is essential to have a high index of suspicion. If the situation suggests that there could be a spinal cord injury the patient must be treated as if there is

• When a history is available and clearly excludes the possibility of a spinal injury or when it is apparent from the injury mechanism that a spinal injury has not occurred, immobilisation of the spine is not necessary.

Neurological examination at the accident site should not be detailed. In motor terms, attendants should be looking at voluntary power, e.g. bending large joints normally. It is important to observe whether the chest wall moves during breathing or whether it is the diaphragm alone which is responsible for respiratory effort (diaphragmatic breathing, see below).

• Do not let the patient get up

• Do not allow others to get the patient up

• Do not get the patient up yourself. Think spinal cord injury!

Sensory levels

• Root of the neck is C4

• The nipple line (in the male) is T4

• The umbilicus is T10

• Foot (sole) is S1.

Immediate management

Because of the risk of anoxic damage and damage from underperfusion, catastrophic haemorrhage <C>, airway (A), breathing (B) and circulation (C) must take priority over a cord injury or a potential cord injury.

The problems found in a primary survey are not only life-threatening but will inevitably make any spinal injury worse. Careful horizontal movement (e.g. a properly applied ‘log roll’), will prevent further permanent damage.

The patient should be moved as little as possible.

Causes of deteriroration in established or suspected spinal injury

• Hypoxia from underventilation, airway obstruction or lung damage either as a result of associated injuries or from aspiration of vomit

• Underperfusion from reduced cord blood flow which may be due to positioning (e.g. sitting up) or to shock

• Mechanical displacement of vertebrae

• Displacement of vertebral fragments.

Reasons for missing a spinal injury

• Stress leading to endorphin release distracting injuries elsewhere or between release and distracting injuries

• Central nervous depression from brain injury

• Intoxication from alcohol or drugs

• Uncooperative or aggressive behaviour.

Emergency extrication

Emergency extrication, that is, without the availability of appropriate extrication devices or the assistance of relevant emergency services, is justifiable only when there is an immediate threat to life.

Airway

Airway obstruction leads to hypoxia and inevitably to cord deterioration. Airway clearance is therefore vital. The technique of jaw thrust (or chin lift if necessary) should be used, while the head and neck are simultaneously moved into a neutral position and manual in-line stabilisation is applied.

Breathing

Ventilation is often impeded in a thoracic or cervical cord injury. This may be because the patient is breathing using only the diaphragm (the intercostal and abdominal muscles being paralysed) or because of chest injuries and associated pain. It should be remembered that pain from chest injuries may mask the pain from the back injury. If ventilation is inadequate ventilatory assistance will be necessary.

Always administer high concentration oxygen

Intubation in potential cord injury

There are benefits in intubating the apnoeic and/or unconscious patient in terms of improved airway control, prevention of subsequent bronchial soiling, ease of bronchial toilet and ease of mechanical ventilation.

The hazards include:

• Neck injury may be associated with laryngeal damage

• Intubation may precipitate vagal asystolic arrest

• Endobronchial suction may precipitate vagal asystolic arrest

• Intubation may precipitate vomiting

• Neck movement may exacerbate a spinal cord injury.

In the majority of cases intubation will not be possible without the administration of anaesthetic drugs since the patient will be conscious.

Indications for intubation include

• Absence of spontaneous ventilation which is not restarted by airway opening

• Absent or inadequate spontaneous ventilation with evidence of vomiting, reflux or aspiration

• Adequate supine spontaneous ventilation which is associated with problems in airway control

• Adequate supine spontaneous ventilation associated with increasing ventilatory difficulty in association with thoracic or abdominal injury

• The unconscious spinal cord injury patient with isolated head and neck injuries

Spinal cord injury and disordered circulation

Spinal cord injury can be associated with disorders of central circulation, which may cause either cardiac arrest or a fatal arrhythmia.

After spinal cord injury, due to loss of function of the sympathetic nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system can be unopposed.

This produces generalised vasodilation. Thus, even if the circulating blood volume is unchanged there will effectively be underperfusion. This produces neurogenic shock.

In an isolated cervical or thoracic cord injury, the ‘normal’ systolic arterial blood pressure will be found to be around 90 mmHg. At this level, because the vessels are vasodilated, perfusion should be adequate so long as the patient is kept flat. The heart rate may be either slow or normal.

A combination of bradycardia and hypotension should always raise the suspicion of spinal cord injury.

Where a patient has a normal pulse and apparent hypotension, both spinal cord injury and covert trauma should be suspected. Shock in the patient with multiple trauma must never be assumed to be solely due to spinal cord injury.

In a patient with multiple injuries of which the cord injury is one element, the indications for infusion are the same as for any other polytrauma victim.

With the isolated cord injury, as may occur in a gymnastic or rugby accident, if given at all, the infusion must be given with extreme care.

So long as the patient is kept flat, perfusion should be adequate to maintain a radial pulse.

Where the radial pulse is lost, an infusion will be necessary to ensure that a palpable radial pulse returns. Only 500 ml of intravenous fluid should be given prehospital. This volume is sufficient to compensate for the increased vascular space.

While a head-down tilt can be used temporarily to clear vomit from the airway, continued use of this position on circulatory grounds may cause the abdominal contents to splint the diaphragm and reduce the vital capacity and so should be avoided.

Neurogenic shock is a cardiovascular condition resulting from loss of vascular tone as a result of loss of sympathetic activity and is manifested by a low blood pressure in a well-perfused individual with no evidence of tachycardia.

Spinal shock is a neurological condition manifested by flaccidity and loss of reflexes.

If the heart rate is below 45 bpm, a bolus dose of atropine (500 μg) should be given before any of the above interventions are attempted and should be given in any case if the heart rate falls as low as 40 bpm.

Unconsciousness

If the patient is alive when the first rescuer arrives, the incidence of a grossly unstable biomechanical cervical injury is of the order of 1 in 300.

Two maxims derive from this:

• In the presence of a significant head injury, a spinal cord injury should always be suspected and movement minimised accordingly

• Because of the relative incidences, any movement which is necessary to save life must take priority and must be carried out in accordance with the priorities of primary survey using the greatest care and best endeavours available.

The major risk of unconsciousness is that of aspiration pneumonia induced by inhalation of vomit or refluxed gastric contents.

Unconsciousness takes priority: the airway must be maintained and bronchial soiling avoided. The mortality of isolated spinal cord injury is under 1%, but this rises to 40% if aspiration pneumonitis supervenes.

The patient with neurogenic shock will appear warm, pink and well perfused, with a low or normal pulse despite a low blood pressure.

Indicators of possible spinal cord injury in the unconscious patient

• Different level of responsiveness above and below the level of possible cord injury

• Diaphragmatic ventilation (during inspiration the abdominal wall, instead of appearing to recede, balloons out)

• Bradycardia with hypotension and a head injury

• Priapism (sustained erection).

Basic management summary

• Always have a high index of suspicion for spinal cord injury

• Remember the history and mechanism of injury

• The patient must not stand or sit up

• Massive haemorrhage, airway, breathing, circulation and unconsciousness require immediate action

• Slow, careful movement is safe

• Careful movement in the horizontal axis preserves life and will also preserve residual cord function.

From this list it can be seen that the basic rules are as follows:

• Consider safety

• Consider the need for resuscitation (primary survey)

• Consider the possibility of a spinal cord injury

• Control the head and neck position while allowing optimal support of the airway, breathing and circulation

• Organise the team before embarking on complicated extrication and management procedures.

The use of equipment will always require assistance beyond the standard two-person ambulance crew. It may involve summoning ambulance colleagues, making use of fellow emergency service professionals or even seeking help from the general public. Assistants must always be adequately briefed before a task is undertaken.

Spinal immobilisation and patient handling

Control of the head and neck

Control of the head and neck must be undertaken as soon as possible. Control is secured by immobilising the base of the skull without exerting a positive traction force. In the unrecognised spinal injury, traction may induce a secondary distraction injury.

Collars

A semi-rigid collar must be used rather than a soft collar, improvised collar or rehabilitation collar.

The collar should restrict flexion, extension, lateral flexion and rotation of the neck and the resting position of the neck must be in neutral alignment.

The instructions for application should be rigorously followed. Another person must always control the head and neck while the collar is applied.

Lastly, any collar is only a restraint and must be supplemented by manual head control or the use of headblocks and tape.

A tight collar may interfere with venous return from the cerebral circulation and accordingly raise the intracranial pressure in patients whose cerebral perfusion is already compromised.

Movement at the accident site

Movement at the scene is usually:

• From prone to supine to maximise ventilation with a conscious patient and place the head in neutral alignment

• From supine to side to protect an otherwise unprotected airway or to assist the clearance of vomit

• From side to supine once vomit has been cleared or to intubate or otherwise maintain ventilation of someone whose ventilation is inadequate on their side.

Movement is effected by a ‘log roll’. The log roll requires ideally six people and at least five people if it is to be carried out without moving the full length of the spine. Log rolling using three people has been described but this produces a movement of the dorsal and/or lumbar spine. Equally, in hospital, four people can be used but this works only where: (a) the conditions are ideal and the patient is at the right height and (b) where the team is highly experienced at the manoeuvre.

Orthopaedic (‘scoop’) stretcher

For retrieving casualties from the ground, the scoop stretcher is preferable to the long spinal board which requires a log roll procedure.

It is almost exclusively a transfer stretcher, although it can be used to remove people from difficult locations, after which they can be transferred to a conventional stretcher or an evacuation mattress.

Once the patient is on the ambulance trolley cot or the evacuation mattress, the scoop stretcher should be removed unless the transfer time to hospital is short.

Evacuation (vacuum) mattresses

The mattress should be tested before the ambulance goes on duty to make sure that there are no leaks.

When laid out it needs to be smoothed flat. Once the patient is positioned on it manual contouring is required between the legs and around the head, neck and shoulders.

The scoop stretcher can be placed underneath it with safety and will add to overall rigidity.

Extrication devices

The designs that are easiest to use have a leading edge which can be applied from either side (and which can be cleared of straps, buckles and other impedimenta so that it can be inserted easily).

A minimum of four people are necessary to apply such a device.

• The ideal device should not ‘concertina’ during insertion behind the patient. It should not be applied before a semi-rigid cervical collar is in place. There should be an effective cushion component to block out the space between the board and the rear of the collar and head. All straps should be applied and tightened, except the leg straps in the presence of a fractured femur

• Once secured, the patient can be moved in any suitable direction except the vertical. A vertical lift requires the addition of a vertical movement harness

• Some devices have what appears to be a handle at the head end. This must never be used for lifting the patient.

Long spinal board

The technique of choice when using a long spinal board is to bring the device in behind the patient from the rear of the wreckage and to move the patient up the long axis of the spinal board.

This requires removal of the roof of the vehicle. If a rapid extrication is mandated by the presence of a time-critical injury, the patient may be rotated onto a spine board through the adjacent doorway of the vehicle.

The spinal board is used with head immobilisers attached to it which prevent lateral movement.

Helmet removal

The removal of motorcycle helmets is essential even in the presence of a spinal cord injury. Opening the visor is not sufficient to manage the airway.

The occipital portion of all helmets will move the head into flexion, reducing the diameter of the spinal canal.

Helmet removal is essential to obtaining neutral alignment of the cervical spine. Helmet removal is not an emergency if the airway is clear and protected.

Helmet removal should, wherever possible, be undertaken by two people.

• First, undo the chin strap

• One person supports the neck from the front and gradually moves their hands up the back of the neck and head while the helmet is tipped backwards and forwards in the vertical plane to clear the occiput and then the nose

• While the helmet is being removed, it should be carefully expanded laterally

• At every stage, the person holding the neck must have complete control and should ask his colleague to stop if problems arise.

Pressure sores

Pressure sores can start to develop within an hour of a spinal cord injury occurring. In the supine position on the heels, the buttocks, the scapulae and the back of the head.

The scoop stretcher can produce pressure sores even on a short journey. It should only be used as a transfer stretcher and patients should not be left lying directly on it.

Ideally the evacuation of spinal injury patients should be carried out on a vacuum mattress. This device is essential for long journeys or secondary transfers or for aeromedical flights.

• Loosen clothing, including the shoe-laces

• Removed hard objects from pockets where they are next to the skin

• Place padding between the legs

• Pad any additional splintage

• Keep the patient on a spinal board for as short a time as possible, ideally no more than 30 minutes

• Remove the spinal board in hospital at the earliest safe opportunity.

Hypothermia

A paralysed person cannot sweat or shiver. Patients with spinal injuries must be protected from the cold; they must be warmed passively by being wrapped up well.

During the primary journey this is not usually a problem, but because of the large distances between spinal units, it can be a problem on a secondary journey from the receiving hospital to the spinal unit, for which the ambulance service is also responsible.

In hot weather the reverse problem – heat illness – can also occur.

For further information, see Ch. 28 in Emergency Care: A Textbook for Paramedics.