CHAPTER 84 Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation

SCI is defined as an injury to the spinal cord that partially or completely interrupts the three main functions of the cord: motor, sensory, and reflex activities. Before World War I, SCI inevitably resulted in early death. Egyptian physicians long ago labeled SCI as an ailment not to be treated at all because they feared the pharaoh would kill them if they let a patient die under their care.1 However, advances in treatment that began during World War II and have progressed since have allowed many persons with SCI to live much longer. Today in many cases, patients with SCI can expect to live an almost normal lifespan. As a result, the numbers of persons alive today with SCI in the United States has increased to more than 200,000.2

Epidemiology

In 1970 the first federally funded Model Spinal Cord Injury Care Systems (MSCICS) were developed. Currently there are 14 such centers (there were 18 before funding was cut) as designated by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDDR). Each center represents a comprehensive interdisciplinary service delivery integrating all aspects of care for the SCI patient from the initial injury to lifelong follow-up. The model centers are based on the principles set forth by Sir Ludwig Guttman, a British physician who pioneered advances in the care of SCI patients during World War II1:

The 14 MSCICS centers and 8 previously designated centers have been contributing clinical information to a national database following a jointly agreed-upon protocol. They have been able to report results on the basis of an estimated 13% of all SCI injuries in the United States occurring since 1973. The database contains information on about 25,000 spinal cord injured persons.3 The end result is a wealth of information regarding injury trends from 1973 to1998 and some recent updates that include information through the year 2004. The data not only allow physicians to know the current status of SCI patients but also give physicians the ability to spot trends in the demographic data. These changes in the demographics of SCI have allowed rehabilitation programs and centers to “change with the times” to reduce the cost and ultimately improve the quality of medical rehabilitative care for their patients with SCI.4

Incidence, Race, Age, and Gender

On the basis of information from the national database, there are approximately 11,000 new cases (40 per million in the U.S. population) each year. However, this number is based on older data from the 1970s. The prevalence is estimated to be 225,000 to 296,000 persons and growing.3 The recently updated national SCI Statistical Center statistics put the prevalence at 255,702.

Between 1973 and 2004, 66% of patients were Caucasian, 21% were African American, and 9.7% were Hispanic.3

Cervical injuries resulting in tetraplegia occur in 54% of SCI patients. Lumbar and thoracic injuries causing paraplegia comprise the rest (45%). A few (1%) were discharged as “normal” or indeterminate. Since 1990, the numbers of patients with complete SCI has been higher than incomplete injuries (56% vs. 44%).3 Since 2000, however, the most frequent injury has been incomplete tetraplegia (34.7), followed by incomplete paraplegia (23.0), complete tetraplegia (18.5), and complete paraplegia (18.5).

SCI affects young adults most often. Population-based data show the highest incidence, nearly 51.6% of injuries, occurs in the 16- to 30-year age group.3 However, the most recent trends suggest that SCI is occurring with increasing frequency in older persons. The result is that the fastest growing population of new SCI patients is older than 60 years of age. Since 1990, the incidence of SCI in persons older than 60 has increased to 12% from 4.5% in the 1970s.3 The average age at SCI has increased from 28.7 to 38.9 as of 2007. Additionally, while SCI is an injury that occurs primarily in males (81.6% since 1973), some centers are reporting increasing numbers of females suffering SCI.

Life Expectance

Life expectancies for persons with SCI that were so low many years ago continue to steadily increase. Mortality rates, however, while improving, continue to be highest during the first year after injury. Complete injuries still have lower ultimate survival rates than incomplete injuries. The degree of neurologic impairment, as measured by the Frankel Grade or the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale, and level of injury were significantly correlated with mortality risk. For example, the average life expectancy of a 20-year-old who suffers complete paraplegia is 66 years. This compares with 61 years for a C5 to C8 SCI, 57 years for a C1 to C4 SCI, and 43 years for a ventilator-dependent patient. This compares with the normal life expectancy in the general population of 77 years and in a patient with incomplete SCI of 72 years.5 The factors that can increase life expectancy are favorable circumstances for good health, community integration, and higher income.6

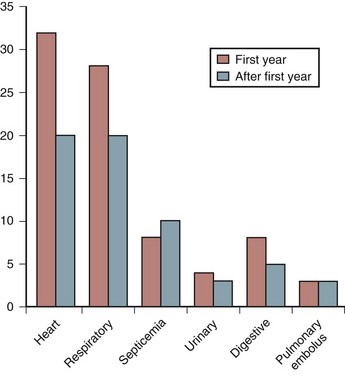

Mortality

Many years ago, the leading cause of death among persons with SCI was renal failure. Pulmonary embolus (PE) usually in the first few weeks after injury, and most often associated with a deep vein thrombosis (DVT), was another frequent cause of death. Advances in urologic management, DVT and PE prevention, and early mobilization have reduced the number of early deaths. Today, renal failure rarely occurs in the acute SCI setting. Because more SCI patients live not only through their first year after injury but also survive to old age, cardiovascular disease has become a more frequent cause of death (Fig. 84–1). Nash and colleagues7 demonstrated that SCI is an independent risk factor for developing multiple risks for cardiovascular disease such as increased cholesterol. Respiratory illness, particularly pneumonia, is now the leading cause of death among older SCI patients with cervical injuries.8 The cause of death in persons with paraplegia is more varied. In addition to heart disease, cancer, suicide, and septicemia are the leading causes.

Etiology

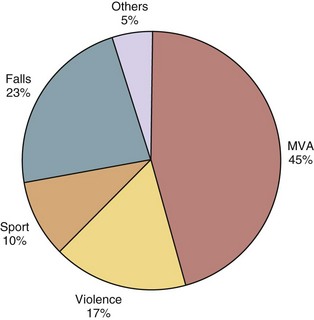

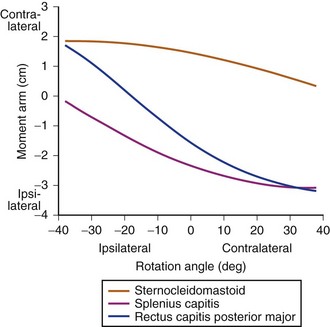

The causes of spinal cord injury are typically divided into traumatic and nontraumatic. The top five causes of traumatic SCI in males are auto accidents, falls, gunshot wounds, diving, and motorcycle accidents.3 The top three remain the same in women, but the final two are medical causes and diving3 (Fig. 84–2).

FIGURE 84–2 Etiology of spinal cord injury by gender of patients.

(Adapted with permission from Jackson AB, Dijkers M, DeVivo MJ, Poczatek RB: A demographic profile of new traumatic spinal cord injuries: Change and stability over 30 years. Arch Phys Med Rehab 85:1740-1748, 2004.)

The major trend is that violent injuries have decreased from 20% in the 1990s to 9.8% in 2000s.3 Geographic variations occur depending on the state or city. In the older SCI patients, in addition to falls, nontraumatic causes of SCI such as cancer, vascular injuries, and infection make up a larger proportion of injuries.

Etiology is also reported in terms of major groups. Figure 84–3 illustrates the frequency that each of these groups causes SCI.

Classification of Spinal Cord Injury

Two assessment tools are used in the evaluation of patients after SCI.9 One is the neurologic classification of SCI using the ASIA impairment scale. The other is the functional score, or Functional Independence Measure (FIM) score.

The ASIA impairment scale measures the degree of completeness of injury using categories from A to E (Table 84–1). Complete paralysis is defined as the absence of sensory and motor function in the lowest sacral segments and incomplete paralysis as preservation of sensation below the level of the injury including the lowest sacral segments. Sacral sparing is defined as voluntary anal contraction or presence of dull touch and pinprick sensation in the rectal and perianal area.

TABLE 84–1 American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale

| Scale Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| A | Complete—No motor or sensory function is preserved in the sacral segments S4-5. |

| B | Incomplete—Sensory but not motor function is preserved below the neurologic level and includes the sacral segments S4-5. |

| C | Incomplete—Motor function is preserved below the neurologic level, and more than half of key muscles below the neurologic level have a muscle grade less than 3. |

| D | Incomplete—Motor function is preserved below the neurologic level, and at least half the key muscles below the neurologic level have a muscle grade of 3 or more. |

| E | Normal—Motor and sensory function is normal. |

FIM score is a widely accepted functional assessment tool and is currently used as an indicator of function in patients with SCI. FIM is an 18-item scale. There are two categories of items, motor and cognitive. Individual items in each category score from 1 to 7, from “total assistance” to “complete independence.” There are 13 items of motor scoring important in determination of self-care, sphincter control, and mobility (Box 84–1). Scores falling below 6 indicate that the patient requires another person for assistance. Many rehabilitation units now use FIM scores to measure patient outcomes. Quality assurance units use these data from groups of patients to draw inferences on the effectiveness of the rehabilitation unit.

Clinical Syndromes

In addition to classifying patients on the basis of their individual motor and sensory injury levels, the following specific clinical syndromes have been identified in the literature: central cord, anterior cord, posterior cord, Brown-Séquard, conus medullaris, and cauda equina syndromes.10,11

Central Cord Syndrome

The most common type of incomplete SCI in the elderly, central cord syndrome also carries with it a relatively favorable prognosis for recovery. The mechanism of injury is usually hyperextension of an already stenotic cervical canal producing central hematomyelia.12 Because the lumbar and sacral motor tracts are located in the periphery of the white matter, the syndrome is characterized by motor weakness of the upper extremities greater than the lower extremities and sacral sparing. Recovery occurs more favorably in younger patients. Between 87% and 97% of patients younger than 50 will eventually ambulate, versus 31% to 41% of those older than 50. Hand intrinsic function is last to recover, usually incompletely in all ages.

Anterior Cord Syndrome

This is an injury to the anterior two thirds of the spinal cord including both gray and white matter. The posterior columns are preserved. The mechanism of injury is either due to thoracic fractures with retropulsion of disc or bone fragments or lesions of the anterior spinal artery. The resulting SCI is most commonly complete paralysis with spasticity. In the lower extremities deep pressure and proprioception are preserved. However, the prognosis for motor recovery is relatively poor.13

Brown-Séquard Syndrome

This injury occurs with a literal or functional hemisection of the spinal cord. The most common cause is a bullet or knife wound. The classic presentation is ipsilateral loss of motor function, ipsilateral loss of dorsal column sensation, and contralateral loss of pain and temperature below the level of the lesion. Overall, these patients have the greatest potential for functional outcome and ambulation (75% to 90%).14 Bowel and bladder continence is regained in 82% and 89%, respectively.

Therapy Approaches

On the rehabilitation unit, the SCI patient begins a new journey. The basic skills of mobility, self-care, and bladder/bowel functions are relearned regardless of the severity of the injury—sometimes quickly but other times painfully slowly. Patients try to achieve independence in each area, although sometimes only modified or partial independence is possible. The level of neurologic injury best predicts the level of independence and mobility each patient can achieve,15 even though individual differences occur. SCI patients use a significant time in rehabilitation to review a variety of handbooks and computer programs to become educated on their injury. Most patients also receive counseling for emotional and psychologic adjustment, discover initial vocational options for their future, and participate in recreational and leisure activities that ease their reintegration into society. A subset of SCI patients who suffered concurrent head trauma receives cognitive testing and retraining. Another subset of SCI patients who remain on ventilators receives breathing and communication training. Finally, each patient is discharged to the most independent living situation possible. Usually they can only go home after multiple modifications are built and after a myriad of adaptive equipment is prescribed.

Because the tasks of rehabilitation can be so daunting and involve so much of the “whole person” with all organ systems including the psychosocial system affected, only a dedicated multidisciplinary team can accomplish a successful comprehensive rehabilitation. Each member of the multiple rehabilitation disciplines functions together as a team to optimize each patient’s outcome.16 Historically the leader of the team has been the rehabilitation physician, or physiatrist, who would create the rehabilitation goals, lead weekly team meetings, and decide when the program is complete. More recently, most rehabilitation programs have shifted to a more patient-centered approach with the interdisciplinary team working toward goals set forth together.17 All disciplines focus their treatments on the patient, so teamwork and treatment overlap are encouraged. With this approach the patient, and often his or her family, is intimately involved in deciding the direction of the rehabilitation and the date of discharge. The individual disciplines are listed in Table 84–2.18

| Discipline | Role |

|---|---|

| Psychiatrist | Medical care, coordination of rehabilitation, team leader |

| Rehabilitation nurse | Daily care, medication, education, reinforce skills, transfers |

| Physical therapist | Gross motor skills, transfers, mobility (wheelchair, standing, ambulation) |

| Occupational therapist | Fine motor skills, activities of daily living (e.g., feeding, dressing, bathing) |

| Recreational therapist | Leisure activities, community reintegration, assistive technology use |

| Social worker | Obtain community resources; assist with disposition planning; communicate with insurance companies |

| Speech therapist | Assess cognitive status; provide communication, swallowing, and cognitive training |

| Respiratory therapist | Manage patients on respirator; provide respiratory treatments |

| Prosthetist/orthotist | Design and fabricate upper/lower extremity braces and prosthesis; fit spine braces |

| Vocational counselor | Test skills and interest; recommend training and assist with placement |

| Vendor | Wheelchair procurement and fitting, adaptive equipment |

Recent advances in rehabilitation techniques have led to both increased functional outcomes and decreased lengths of stay. One of the most influential advances has been in surgical stabilization. Historically, large bulky cervical braces including halos dominated rehabilitation units. Now, better internal fixation has allowed patients to come onto the rehabilitation units almost immediately after surgery and usually with only a hard collar.19 The less intrusive bracing allows patients to progress more quickly in their mobility training.

Many advances in therapy techniques have improved treatment offered to SCI patients in rehabilitation. Functional electrical stimulation (FES) has been applied to patients both in the acute rehabilitation setting and later in the outpatient setting to upper and lower extremities.20 Assisted or weighted standing and walking, even with patients with complete injuries, is now being tried in a few centers with promising early results.21 Technology and equipment innovation has influenced greatly the quality of care SCI patients receive. Power wheelchairs now have standing options, more rugged wheels, and automatic pressure relief. Manual chairs are now fitted with more advanced cushions, sport options, and “power-assist” wheels. Most cars and vans are outfitted with hand controls. Finally, computerized environmental control units and voice-activated systems have improved independence and freedom for patients with high-level tetraplegia.

Because shorter lengths of stay have moved patients home sooner, the majority of rehabilitation gains often occur in the outpatient setting. Patients with “chronic SCI,” some years after their injury, are even seeing benefits from renewed or prolonged rehabilitation. Jacobs and colleagues22 showed improvements in cardiovascular status after circuit strength training in SCI patients. Competitive sports for patients with disabilities offer not only physical but also psychologic benefits. Technology has also fueled growth in the rehabilitative treatment of SCI patients long after injury. Tendon transfers had been coupled with the “freehand” implant to improve hand function in many tetraplegic patients.23 Bladder implants or injections of botulinum toxin may reduce incontinence,24 intrathecal baclofen pumps reduce malignant spasticity,25 and FES implants have allowed for limited amounts of standing and ambulation.26 All of these devices can increase functional independence in the appropriate SCI candidate but also require postplacement rehabilitation training.27

Medical Management

Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction

Neurogenic bowel dysfunction is common after SCI and has the potential to influence the social, emotional, and physical well-being of patients. Establishment of an effective bowel program during rehabilitation can minimize the development of disability related to neurogenic bowel. The goal is to control severe constipation, promote regularity, and prevent involuntary bowel movements. Two types of neurogenic bowel dysfunction after SCI exist: reflexic and areflexic.28

Reflexic or UMN bowel dysfunction is seen in patients with SCI above the conus medullaris. Voluntary control of bowel is lost in these patients, but conus-mediated reflex activity and intestinal peristalsis are intact. The external anal sphincter becomes spastic because of the spasticity of the pelvic floor preventing stool evacuation. Stool accumulates in the colon unless reflex defecation is triggered. Bowel care in these patients includes (1) nutritional changes with increased fiber and fluid intake, (2) oral medication (lubricants and cathartics), (3) rectal chemical stimulation (suppositories or enema), and (4) mechanical digital stimulation.29

Areflexic or lower motor neuron (LMN) bowel dysfunction is a result of lesions at or below the conus medullaris. Voluntary control of bowel is lost, as well as sacral reflex activity. The external anal sphincter becomes atonic and flaccid, which increases the risk of fecal incontinence. Management of LMN bowel dysfunction includes (1) diet with fiber and some fluid restriction, (2) oral medication (bulk-forming agent), and (3) mechanical digital removal of stool.29

Neurogenic Bladder Dysfunction

Urosepsis was the leading cause of death before introduction of intermittent catheterization (IC).30 Urologic problems are the most common complications of SCI. The rate of urinary tract infections (UTIs) is 50% to 80% in the first year postinjury. The goal of bladder management during rehabilitation is to establish an effective and safe method of emptying the bladder and avoiding incontinence. Two types of neurogenic bladder dysfunction exist: reflexic and areflexic.

Management of neurogenic bladder after SCI is similar for both types. The routine recommendations are based on clinical practice guidelines prepared by the Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine31:

Spasticity

Spasticity is seen frequently in patients after SCI. In 37% of patients the spasticity is significant and requires chronic therapy. Spasticity may interfere with function, daily activities, and sleep. The severity of spasticity during rehabilitation in SCI patients varies. It has been reported that patients with cervical and upper thoracic injuries have a higher incidence of spasticity than patients with lower spine injuries.32 The underlying processes involved in pathogenesis of hyperactive reflexes are multifactorial and involve both inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters. The role of neurotransmitters in spasticity is not fully understood; therefore the therapy is generally symptomatic. Immediately after SCI there is a short period (2 to 3 weeks) of areflexia that is followed by a gradual occurrence of increased muscle tone below the level of injury. In mild to moderately severe cases, ROM and static stretching can be used to treat spasticity during rehabilitation. Medication is usually indicated for severe and chronic spasticity. The different drugs that can be used for spasticity are in order (1) baclofen, (2) benzodiazepines, (3) tizanidine, and (4) dantrolene. Baclofen is a GABA agonist, a major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS). The starting dose is 5 mg three times per day and increased slowly to avoid side effects. The standard maximum dose is 80 mg/day divided either into TID or QID dosing (although some practitioners will go higher). For refractory and severe spasticity, baclofen can be given by intrathecal pump, which will reduce the therapeutic dose 100 times and will also markedly decrease sedative side effects of the drug on the CNS.

Cardiovascular Complications

The primary mechanisms underlying cardiovascular abnormalities are related to the disruption of sympathetic control located in the cervical cord. The most frequent symptoms are orthostatic hypotension (68%) and bradycardia (71%).33 Autonomic dysreflexia develops in patients with SCI above the T6 spinal segment.

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) is a serious complication after SCI34. It is characterized by a sudden onset of pounding headache, increase of blood pressure, and bradycardia. AD occurs in patients with SCI above the T6 spine segment. These patients have interrupted central inhibitory control of the thoracic sympathetic system. Therefore, various peripheral noxious stimuli below the injury (i.e. bladder distension, pressure ulcers, ingrown toenails, UTI, constipation, etc.) may lead to overstimulation of the sympathetic system. AD may have different causes, however it is most commonly related to bladder or bowel distension34. Treatment of AD includes immediate repositioning of patient in a sitting position and loosening of clothing or constrictive devices to allow a pooling of blood into the lower extremities. The placement of an indwelling catheter should be performed early because the most common cause of autonomic dysreflexia is bladder distension. If after the catheterization systolic blood pressure remains elevated over 150 mm Hg, an antihypertensive agent with rapid onset and short duration (i.e., nitrates or nifedipine) is recommended34. If bowel distension or impaction is suspected, antihypertensive medication needs to be administered prior to rectal examination for stool.

The incidence of thromboembolism is high in the acute stage of SCI. The routine screening for deep vein thrombosis (DVT) showed positive results in 47% to 100% of patients.35 Studies based on clinical parameters estimated a lower incidence of DVT in acute SCI. The incidence of clinically diagnosed DVT was 11.4% in 1996, which was significantly reduced to 5.2% in 1998. The decline in the incidence of DVT is most likely the result of introduction of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH).36 Prevention of thromboembolism starts after injury and continues throughout rehabilitation. Current methods for prevention of thromboembolism used in the SCI patients are mechanical (compression hose, boots, pneumatic devices), pharmacologic (unfractionated heparin, LMWH, warfarin), and inferior vena cava filter. A consortium organized by Paralyzed Veterans of America in 199735 recommended mechanical prevention for the first 2 weeks following injury. In patients with motor complete SCI, pharmacologic prevention with unfractionated heparin or LMWH is recommended for a minimum of 8 weeks or until discharge from the rehabilitation center. Patients with motor complete injuries and risk factors such as obesity, heart failure, cancer, lower extremity fractures, previous DVT, or age older than 70 may need their prevention extended after discharge. The most recent recommendation for the prevention of thromboembolism in the rehabilitation phase of patients with SCI is based on the sixth ACCP consensus in 2001.37 LMWH or full-dose oral anticoagulation with warfarin was the initial recommended method with IVCF recommended in patients who failed or have contraindications to anticoagulation. Treatment of thromboembolism in patients with SCI does not differ from treatment currently used in non-SCI patients.

Respiratory Complications

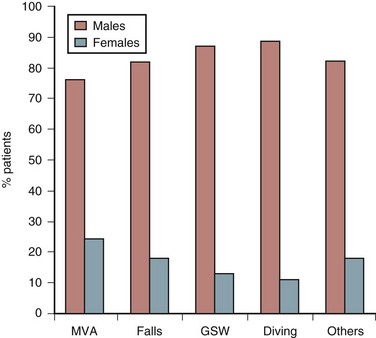

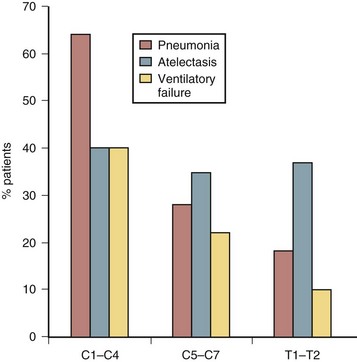

Respiratory complications are the most common early and late causes of death after SCI. Figure 84–4 shows the most common respiratory complications in patients with different levels of SCI.38 Pneumonia is the most common complication in high-level injuries, whereas atelectasis is seen in all groups of patients in similar frequency regardless of level of injury. Smith and coworkers found in more than 18,000 veterans with SCI a steady rate of visits for acute respiratory infection, without a declining trend in frequency.39

FIGURE 84–4 Respiratory complications after spinal cord injury.

(Adapted with permission from Jackson AB, Grooms TE: Incidence of respiratory complications following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab 75:270-275, 1994.)

There are several factors important in genesis of ventilatory abnormalities after SCI40 such as (1) restrictive ventilatory dysfunction as a result of muscle paralysis, (2) inability to cough, which is due primarily to paralysis of abdominal and intercostal muscles, and (3) hypersecretion of mucus. Overproduction of mucus (about 1 L/day) is due to absent sympathetic outflow and unopposed parasympathetic tone that also leads to bronchoconstriction.

Pressure Ulcers

SCI causes profound changes in the structure and physiology of the skin, which leaves patients susceptible to the development of pressure ulcers. The incidence of pressure sores after SCI is high, with approximately 50% of chronic patients with SCI developing a pressure ulcer in their lifetime. Pressure ulcers are seen on the sacrum in 26%, ischium in 23%, heel in 12%, and trochanter in 10% of chronic SCI patients.41 Several factors are responsible for the development of pressure ulcers after SCI, but most important is prolonged pressure over a bone prominence. The cornerstones in the prevention of pressure ulcers are regular daily inspection of skin and the performance of pressure relief techniques.

Heterotopic Ossification

Heterotopic ossification (HO) is another early complication after SCI. Often occurring in the first month of rehabilitation, HO is often a cause of “fever of unknown origin.” The incidence of HO after SCI is about 50%.42,43 The etiology of HO is unknown. The pathology of HO is characterized by bone growth in extra-articular tissue of paralyzed extremities. Clinically, in the acute stage of HO the most common findings are swelling, fever, and reduction in ROM of affected joint(s). The level of creatine phosphokinase (CPK) in serum in the early stage may indicate the severity of muscle involvement. In the chronic stage, HO may limit the functional status of the patient. Diagnosis of HO in the early stages is based on a positive three-phase bone scintigraphy with 99m Tc diphosphonate. Prevention of HO with indomethacin in patients with SCI is effective if started early (3 to 4 weeks) after injury.44 Etidronate is often prescribed to treat HO in the acute stage along with aggressive joint motion by a physical therapist. Only when the heterotopic bone is mature up to 1 year after the onset can surgical resection be considered.

Osteoporosis and Fractures

In patients with SCI there is a significant bone loss in paralyzed limbs in the early period after injury. The most severely involved skeletal regions are the distal femur and proximal tibia. Bone densitometric studies showed that patients with complete paralysis might have bone loss of 30% in the first 3 months.45 In later periods bone loss will continue at a slower rate, reaching a new steady state after 2 years. At the final stages bone mineral loss can be about 30% in the femoral shaft and 50% in the proximal tibia.46 Patients who actually suffer fractures were found to have even higher bone loss; about 40% in femoral shaft and 70% in proximal tibia. Presently there is no cure for osteoporosis after SCI. Many different preventive programs for bone loss have been evaluated. So far, all preventive measures have shown some positive effect on bone mass, but the effects are transient and the bone loss resumes as soon as the intervention stops. The incidence of lower extremity fractures after SCI is about 1% to 2% per year. Lower limb fractures are most often treated using a nonsurgical approach with the goal of maintaining functional independence. Use of splints and early mobilization are generally allowed initially in a supervised setting.

Pain

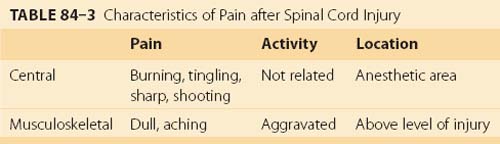

Pain prevalence is stable over time ranging from 81% at 1 year after injury to 83% at 25 years.47 Approximately 90% of patients with SCI have a delayed onset of pain, and many of them are not finding an adequate pain relief from commonly used medication.48 Nepomuceno and colleagues49 described the negative impact of pain on the life of patients with SCI. Thirty-seven percent of patients with cervical injuries and 23% of patients with lower level of SCI reported that if they had the chance, they would trade pain for loss of bladder, bowel, or sexual function. Most patients describe pain as stable or controlled, while the others report that pain increased their disability. Of the different classifications of pain after SCI, the most commonly described are central neuropathic and musculoskeletal pain.50,51 Clinical differentiation between central neuropathic and musculoskeletal pain is shown in Table 84–3.

Outcomes of Rehabilitation

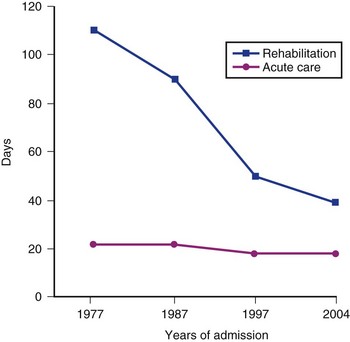

Length of Stay

In general, patients with tetraplegia need a longer period for rehabilitation than patients with paraplegia. Similarly, patients with complete paralysis require a longer stay at rehabilitation centers than with incomplete paralysis. Recent statistical analysis showed that time needed for acute care has not changed during the past 20 years; however, significant changes were found in the length of stay (LOS) at the rehabilitation centers (Fig. 84–5). Figure 84–5 illustrates results from a database derived from the National database.5 A dramatic reduction of LOS was documented at rehabilitation centers across the country from 1977 to 2000. The average length of stay was 106 days in 1977, 90 days in 1987, 51 days in 1997, and 39 in 2004. The changes in the LOS of patients after SCI can mainly be attributed to measures that managed care instituted in the early 1990s.

Discharge Disposition

The changes in the length of stay of patients at rehabilitation centers had some effect on the discharge disposition of these patients. The results from the national database4 obtained in 1997 showed that the majority of patients were still discharged home (91.2%); however, the percent of patients discharged to skilled nursing homes also increased (5.3%) as compared with 2.8% in 1990.

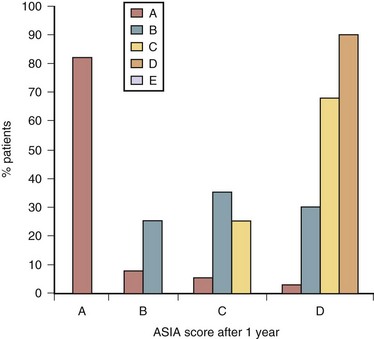

Gain of Motor Function

The outcomes of motor function are determined by the previously discussed ASIA standard evaluation by using the ASIA system and data obtained from the national database.52 The outcomes of motor function were related to rehabilitation and neurologic recovery and shown in Figure 84–6. As illustrated in Figure 84–6, about 10% to 15% of patients diagnosed as complete (ASIA “A”) will convert in 1 year to incomplete ASIA “B,” “C,” or “D.” Usually neurologic return of motor function starts in the first month after injury but may continue up to 24 months. Despite recent advances in pharmacologic treatment of spinal cord injury, prognosis for recovery of patients with initial ASIA “A” remains poor. The prognosis for motor function recovery of patients with ASIA “B” designation is intermediate. One third of these patients remain unchanged, one third converts to ASIA “C,” and one third to ASIA “D” or “E.” In the group of patients with ASIA “C” designation, 70% will convert to ASIA “D.” Patients with initial ASIA “D” designation showed functional improvement to “E” in 4%, whereas 96% of these patients remained in the “D” category. Even after 5 years from traumatic SCI, results are not very different. Kirshblum and colleagues53 found that only 4.5% of patients with motor complete paralysis regained some motor or sensory recovery.

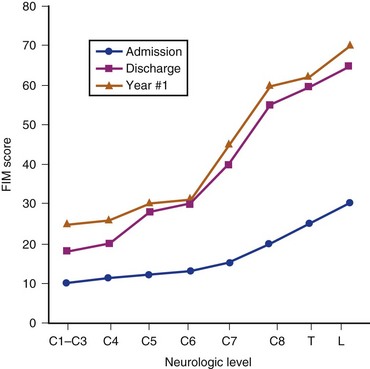

Functional Independence (Charting ADL Improvement Objectively)

Currently the most widely used validated ADL evaluation scale is the functional independence measure (FIM).54 The FIM instrument evaluates nine areas of self-care and can be applied multiple times throughout the course of treatment not only to provide a baseline of function but also to chart improvement in these key areas. The areas that the FIM reports on are self-feeding; grooming; bathing; dressing upper and lower body; toileting; and transfer to the toilet, tub, or shower. The FIM has demonstrated a high degree of inter-relater reliability.55After the SCI patient leaves the hospital, the FIM can be continued in a self-reporting form (FIM-SR). Masedo and colleagues found the FIM-SR motor scales and total FIM-SR score to be reliable and valid measures of perceived functional independence in individuals with SCI.56

Figure 84–7 shows the results from the national database on FIM scores.57 The data were obtained on admission and discharge from rehabilitation and at the follow-up after 1 year. There is a marked difference in FIM motor scores from admission to discharge from rehabilitation in all neurologic groups of patients. The greatest improvements are seen in patients with lower cervical and thoracolumbar injuries. There was little change in FIM scores in all categories of patients beyond discharge from rehabilitation. Figure 84–7 illustrates mean FIM motor scores for each neurologic group of patients and indicates that a score of 78 (13 motor items with scores of 6), correlating with functional independence, is reached only in patients with thoracolumbar injuries.

Therefore the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III, revised three times) created a new, more comprehensive measure applicable to persons with paraplegia and tetraplegia, complete and incomplete.58 Itzkovich and colleagues59 found total agreement between raters was above 80% in most SCIM III tasks. They also found the SCIM III was more responsive to changes than FIM in the subscales of respiration and sphincter management and mobility indoors and outdoors. The measure is now undergoing final studies to see if it is more sensitive or specific for SCI-injured persons than other measures while maintaining the practicality of the FIM.

Employment

More than half (57.4%) of those persons with SCI admitted to a model system reported being employed at the time of their injury. The postinjury employment picture is better among persons with paraplegia than among their tetraplegic counterparts. By postinjury year 10, 32.4% of persons with paraplegia are employed, whereas 24.2% of those with tetraplegia are employed during the same year. National data from Model System Spinal Cord Centers revealed that the rate of employment of SCI patients is approximately 27% after rehabilitation.60 Similar results were found for both genders, 24.1% in female patients and 27.7% in male patients. Important factors in obtaining employment after SCI were age, severity of injury, and educational level before injury.

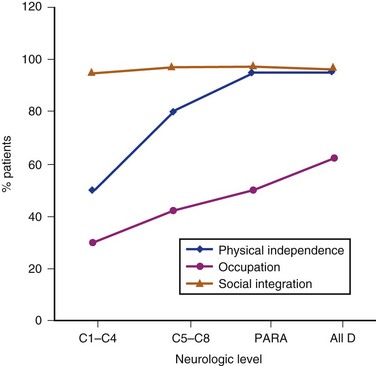

Community Integration

Community integration of patients with SCI starts during inpatient rehabilitation and continues after discharge from rehabilitation center. The involvement of human services plays a major role in assisting patients in the community. Figure 84–8 depicts the three aspects of community integration after SCI: functional independence, social integration, and occupation. Data obtained from the national database61 indicate high levels of social integration in all neurologic groups of patients after SCI. The lowest median score of community integration was found in occupation, as discussed in the paragraph earlier. Community and athletic groups increase the levels of community integration. Activities that injured persons used to participate in can be modified for the wheelchair athlete or participant, increasing the quality of life for those injured. The sports include sailing programs, diving programs, wheelchair basketball teams, skiing, rugby, marathon racing, and Paralympic competitions.

Reintegration into the Environment

As a part of most inpatient rehabilitation treatment programs, the “home evaluation” and “home visit” are highly anticipated. The feeling that the home visit must mean the end of the inpatient portion of rehabilitation is near excites and further motivates the SCI patient to reach his or her goals and participate fully. However, evaluating the home environment as early as possible in the rehabilitation process is also important so that appropriate goals can be set and needed modifications can begin earlier.62

The second component of the evaluation concerns the home structure itself. The therapist must create a picture of the home and environment that will allow for an understanding of what impediments might exist and what might pose a barrier to maximizing function. Through knowing the individual limitations of the patient, the therapist can set therapy goals that may also involve making modifications to the home and environment to maximize function.63 Ultimately, by marrying the functional abilities of each injured patient to the environment that he or she is going to live within, the interdisciplinary rehabilitation team can help to maximize the quality of life of each SCI patient.

Pearls

Pitfalls

Key Points

1 Kirshblum S, Campangnolo DL, DeLisa JA, editors. Spinal Cord Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins, 2002.

2 Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Vol 80, Nov 1999.

Entire issue devoted to reviewing SCI model systems data and outcomes in patients with SCI.

3 Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GT, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2001;119:132S-175S.

The most recent consensus definition of DVT prevention after SCI.

4 Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Acute Management of Acute Autonomic Dysreflexia. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25:S67-S88.

This is considered as a guideline in the management of autonomic dysreflexia.

5 Consortium Spinal Cord Consensus. Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Treatment Following Spinal Cord Injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2001;24:S39-S101.

1 Apple DFJr. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. In: Rothman RH, Simeone FA, editors. The Spine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998:1225-1246.

2 DeVivo MJ. Epidemiology of Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. In: Kirshblum S, Campagnolo DL, DeLisa JA, editors. Spinal Cord Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2002:69-81.

3 Jackson AB, Dijkers M, DeVivo MJ, Poczatek RB. A Demographic Profile of New Traumatic Spinal Cord Injuries: Change and Stability over 30 Years. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2004;85:1740-1748.

4 Lammertse DP, Jackson AB, Sipski ML. Research from Model Spinal Cord Injury Systems: Findings from the Current 5-Year Grant Cycle. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2004;85:1737-1739.

5 Facts and figures at a glance from National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center, Birmingham, Alabama. J Spinal Cord Med. June, 2006.

6 Krause JS, DeVivo MJ, Jackson AB. Health status, community integration, and economic risk factors for mortality after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2004;28:1764-1773.

7 Nash MS, Jacobs PL, Mendez AJ, et al. Circuit resistance training improves the atherogenic lipid profiles of persons with chronic paraplegia. J Spinal Cord Med. 2001;24:2-9.

8 Frankel HL, Coll JR, Charlifue SW, et al. Long term survival in spinal cord injury: A fifty-year investigation. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:266-274.

9 Kirshblum S, Donovan WH. Neurologic assessment and classification of traumatic spinal cord injury. In: Kirshblum S, Campagnolo DL, DeLisa JA, editors. Spinal Cord Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2002:82-95.

10 Bing R. Compendium of regional diagnosis in affection of the brain and spinal cord, ed 2. New York: Rebman; 1911.

11 Schneider RC, Cherry GR, Patek H. Syndrome of acute central cervical spinal cord injury with special reference to mechanisms involved in hyper-extension injuries of the cervical spine. J Neurosurg. 1954;11:546-577.

12 Quencer RM, Bunge RP, Egnor M, et al. Acute traumatic central cord syndrome: MRI pathological correlations. Neuroradiology. 1992;34:85-94.

13 Cheshire WP, Santos CC, Massey EW, et al. Spinal cord infarction: etiology and outcome. Neurology. 1996;47:321-330.

14 Roth EJ, Park T, Pang T, et al. Traumatic cervical Brown-Séquard and Brown-Séquard plus syndromes: The spectrum of presentations and outcomes. Paraplegia. 1991;29:582-589.

15 Kirshblum SC, O’Connor KC. Predicting neurologic recovery in traumatic cervical spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:1456-1466.

16 Ragnarsson KT, Gordon WA. Rehabilitation after spinal cord injury: the team approach. Phys Med Rehabil Clin North Am. 1992;3:853-878.

17 Zigler JE, Atkins MS, Resnik CD, et al. Rehabilitation. In: Levie AM, Eismont FJ, Garfin SR, Zigler JE, editors. Spine Trauma. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998:567-596.

18 Banovac K, Fertel D, Bauerlein J. Principles of Rehabilitation Medicine. In: Humes D, editor. Kelly’s Textbook of Internal Medicine. ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2000:308-313.

19 Askins V, Eismont FJ. Efficacy of five cervical orthoses in restricting cervical motion: a comparison study. Spine. 1997;22:1193-1198.

20 Stein RB, Chong SL, James KB, et al. Electrical stimulation for therapy and mobility after spinal cord injury. Prog Brain Res.. 2002;137:27-34.

21 Field-Foote EC, Tepavac D. Improved intralimb coordination in people with incomplete spinal cord injury following training with body weight support and electrical stimulation. Physical Therapy. 2002;82:707-715.

22 Jacobs PL, Nash MS, Rusinowski JW. Circuit training provides cardiorepiratory and strength benefits in persons with paraplegia. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:711-717.

23 Kilgore KL, Peckham PH, Keith MW, et al. An implanted upper-extremity neuroprosthesis follow-up of five patients. J Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79A:533-541.

24 Creasey GH. Electrical stimulation of sacral roots for micturition after spinal cord injury. Urol Clin North Am. 1993;20:505-515.

25 Coffey RJ, Cahill D, Steers W, et al. Intrathecal baclofen for intractable spasticity of spinal origin: results of a long term multi-center study. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:226-232.

26 Yarkony GM, Roth EJ, Cybulski GR, et al. Neuromuscular stimulation in spinal cord injury: restoration of functional movement of the extremities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73:78-86.

27 Moynahan M, Mullin C, Cohn J, et al. Home use of a functional electrical stimulation system for standing and mobility in adolescents with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med and Rehabil. 1996;77:1005-1013.

28 Stiens SA, Bergman SB, Goetz LL. Neurogenic bowel dysfunction after spinal cord injury: Clinical evaluation and rehabilitation management. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1997;78:S86-S102.

29 Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Neurogenic Bowel Management in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998.

30 Guttman L, Frankel H. The value of intermittent catheterization in the early management of traumatic paraplegia and tetraplegia. Paraplegia. 1966/1967;4:63-84.

31 Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Bladder management for adults with SCI. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29:532-567.

32 Maynard FM, Karunas R, Waring WW. Epidemiology of spasticity following traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1990;71:566-569.

33 Lehman KG, Lane JG, Piepmeier JM, Batsford WP. Cardiovascular abnormalities accompanying acute spinal cord injury in humans: Incidence, time course and severity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10:46-52.

34 Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Acute Management of Acute Autonomic Dysreflexia. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25:S67-S88.

35 Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Prevention of Thromboembolism in Spinal Cord Injury. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1997.

36 Chen D, Apple DF, Hudson LM, Bode R. Medical complications during acute rehabilitation following spinal cord injury—Current experience of the Model Systems. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1997;80:1397-1402.

37 Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GT, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2001;119:132S-175S.

38 Jackson AB, Grooms TE. Incidence of respiratory complications following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1994;75:270-275.

39 Smith BM, Evans CT, Kurichi JE, et al. Acute respiratory tract infection visits of veterans with spinal cord injury and disorders: Rates, trends, and risk factors. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:355-361.

40 Lanig IS, Peterson WP. The respiratory system in spinal cord injury. Phys Med Rehab Clin North Am. 2000;11:29-37.

41 Consortium Spinal Cord Consensus. Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Treatment Following Spinal Cord Injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2001;24:S39-S101.

42 Banovac K, Renfree KJ, Hornicek FJ. Heterotopic ossification after brain and spinal cord injuries. Clin Rev Phys Rehab Med. 1998;10:223-256.

43 Van Kuijuk AA, Geuts ACH, van Kupperelt HJM. Neurogenic heterotopic ossification after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:313-326.

44 Banovac K, Williams JM, Patrick LD, et al. Prevention of heterotopic ossification after spinal cord injury with indomethacin. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:370-374.

45 Garland DE, Stewart CA, Adkins RH, et al. Osteoporosis after spinal cord injury. J Ortho Res. 1992;10:371-378.

46 Biering-Sorensen F, Bohr H, Schaadt O. Bone mineral content of the lumbar spine and lower extremities years after spinal cord lesion. Paraplegia. 1988;26:293-301.

47 Cardenas DD, Bryce TN, Shem K, et al. Gender and Minority Differences in the pain experience of people with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2004;85:1774-1781.

48 Cardenas DD, Jansen MP. Treatment of chronic pain in persons with spinal cord injuries: A survey study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29:109-117.

49 Nepomuceno C, Fine PR, Scott Richards J, et al. Pain in patients with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1979;60:605-609.

50 Siddal PJ, Taylor DA, Cousins MJ. Classification of pain following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:69-75.

51 Cardenas DD, Turner JA, Warms CA, Marshall HM. Classification of chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1708-1714.

52 Marino RJ, Ditunno J, Donovan WH, Maynard F. Neurological recovery after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1999;80:1031-1396.

53 Kirshblum S, Millis S, McKinley W, Tulsky D. Late neurologic recovery after traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2004;28:1811-1817.

54 McKinley W, Santos K, Meade M, Brooke K. Incidence and outcomes of spinal cord injury clinical syndromes. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30:215-224.

55 Ottenbacher KJ, Hsu Y, Granger CV, Fiedler RC. The reliability of the functional independence measure: a quantitative review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:1226-1232.

56 Masedo AI, Hanley M, Jensen MP, et al. Reliability and validity of a self-report FIM (FIM-SR) in persons with amputation or spinal cord injury and chronic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84:167-176.

57 Hall KM, Cohen ME, Wright J, et al. Characteristics of the functional independence measure in traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1999;80:1471-1476.

58 Catz A, Greenberg E, Itzkovich M, et al. A new instrument for outcome assessment in rehabilitation medicine: Spinal cord injury ability realization measurement index. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:399-404.

59 Itzkovich M, Gelernter I, Biering-Sorensen F, et al. The Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM) version III: Reliability and validity in a multi-center international study. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1926-1933.

60 Stuart Krause J, Kewman D, DeVivo MJ, et al. Employment after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1999;80:1492-1500.

61 Whiteneck G, Tate D, Charlifue S. Predicting community integration after spinal cord injury from demographic and injury characteristics. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1999;80:1485-1491.

62 Culler KH. Home management. In: Crepeau EB, Cohn ES, Schell BAB, editors. Willard and Spackman’s Occupational Therapy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:534-541.

63 Cooper BA, Cohen U, Hasselkus BR. Barrier free design: A review and critique of the occupational therapy perspective. Am J Occupational Ther. 1991;45:344-350.