9 Spinal cord injury and disease

Part 1 Spinal cord injury (SCI)

Incidence and mortality

SCIs affect only a small percentage of the population, with a male-to-female ratio of 5:1. A total of 17.2 people per million of the population in Europe suffer a traumatic SCI and 8.2 per million experience a non-traumatic SCI (figures from 2001: [1]).

Diagnosis and prognosis

Diagnosis is dependent upon the completeness of the lesion and must take into account the infinite variations of this. Prognosis is irretrievably linked with this. The most useful current classification is the American Spinal Injuries Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (Table 9.1). This scale is reasonably predictive of diagnosis and makes for a logical subclassification of incomplete spinal column injuries into clinical syndromes:

Table 9.1 American Spinal Injuries Association (ASIA) impairment scale

| A | Complete: no motor or sensory function is preserved in the sacral segments S4–S5 |

| B | Incomplete: sensory but not motor function is preserved below the neurological level and extends through the sacral segments |

| C | Incomplete: motor function is preserved below the neurological level, and the majority of key muscles below this level have a muscle grade less than 3 |

| D | Incomplete: motor function is preserved below the neurological level, and the majority of key muscles below this level have a muscle grade greater than or equal to 3 |

| E | Normal: motor and sensory function is normal |

Medical treatment

SCI and physiotherapy

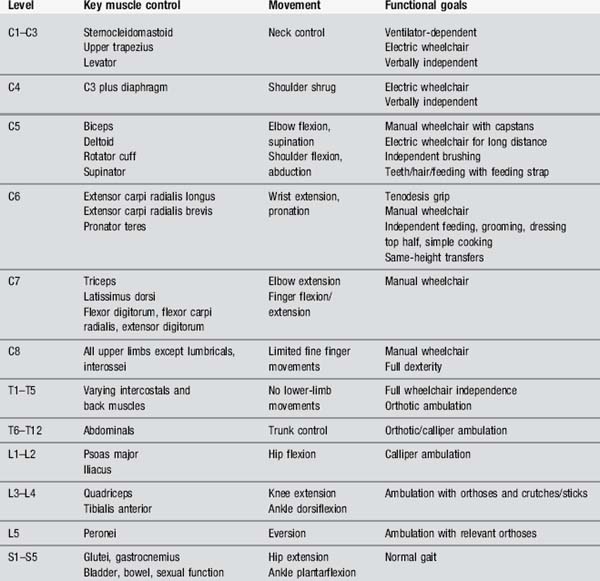

Given the complexity of the possible changes, a clear knowledge of anatomy and associated nerve roots is vital. In order to know what can reasonably be expected by way of recovery, accurate location of the level of the spinal cord lesion is very important. Table 9.2 offers the range of possible goals and should be considered in conjunction with Table 2.2 in Chapter 2.

Acupuncture in SCI

The studies have been small but suggestive of a positive role for acupuncture [5]. A group of 22 patients with SCI who experienced moderate to severe pain of at least 6 months’ duration were given a course of 15 acupuncture treatments over a 7-week period. In a more general review of complementary therapies for SCI, Nayak et al. suggest that, while acupuncture may have a place in pain control, massage has been shown to be even better and is apparently rarely used [6].

The combination of acupuncture technique and ‘moving cupping’ (see Chapter 12) could be very useful.

The same research group also looked into the effect of acupuncture on autonomic dysreflexia [7], and decided that, although none of their – admittedly small – sample of 15 patients went on to develop symptoms of autonomic dysreflexia, three of the total did display an acute elevation of blood pressure, making it desirable to monitor this type of patient carefully in future.

Achieving bladder control is an important issue for both the patients and their carers and there has been a preliminary study which offered a role for acupuncture. The potential mechanism, through afferent stimulation at the same segmental level using the points CV 3 and CV 4 and also reflex stimulation of the splanchnic nerves at sacral level using BL 32, seems logical in both anatomical and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) terms. The trial has been criticized for general lack of rigour but they did observe in post hoc analysis that those patients receiving acupuncture within the first 3 weeks did better with achieving bladder balance [8].

Body acupuncture

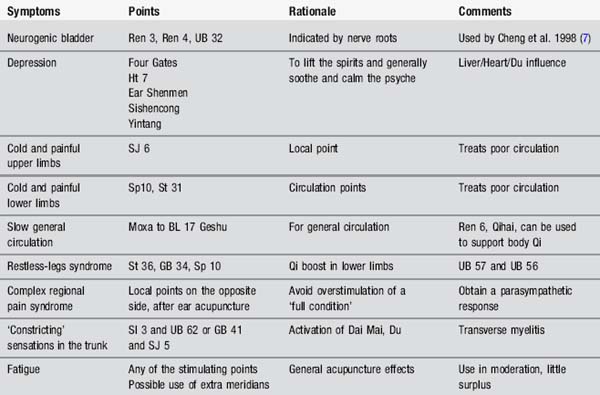

Acupuncture points, mainly on Yang meridians, can be used, as in all neurological diseases, to tackle the superficial musculoskeletal symptoms. Both pain and movement problems can be addressed. The points can be selected according to symptoms and Table 9.3 gives some of the alternatives.

Scalp acupuncture

The authors have been unable to find any convincing evidence for the use of scalp acupuncture in SCI. There is some anecdotal evidence, provided by practitioners of Yamamoto New Scalp Acupuncture (YNSA), of success with neurological conditions, but this technique of scalp acupuncture is slightly different to the Chinese version (see Chapter 12) and has a very limited evidence base. The main claim seems to suggest a change in neuroplasticity.

TCM approach

TCM regards injury to the spinal column as a direct injury to the Du meridian; thus points associated with that meridian, such as SI 3 Houxi and BL 62 Shenmai, can be used. The Huatuojiaji points are seen as valuable, being closely situated as they are, and this fits well with the neuroanatomy of the problem. The Huatuojiaji points are described as being able to ‘activate the primordial energy’ in the Du meridian [9]. Generally one would not needle the Du points but some authorities recommend this, choosing points above and below the level of damage and combining these with Huatuojiaji points.

The most likely TCM syndromes involved will be Qi and/or Blood deficiency and Liver and Kidney Yin deficiency [10].

Case study 9.1: level 1 case study: partial spinal cord injury

Part 2 Transverse myelitis

Incidence and mortality

Transverse myelitis can occur at any age, in adults and children, male or female. Conservative estimates of incidence per year vary from 1 to 5 per million population [11].

Medical treatment

Corticosteroids may be used in the early stages in an attempt to decrease the inflammation.

Prognosis

Recovery is often good and should commence within 1–3 months after onset. It may be partial or can be complete but the prognosis is relatively poor if there is no sign by 3 months [12]. In fact most patients will make a reasonable recovery but there may be a tendency to relapse if there is underlying serious illness.

Transverse myelitis and physiotherapy

Acupuncture in transverse myelitis

There is no supporting research for acupuncture in this condition but a very detailed case report was published recently where acupuncture was used to treat sleep disturbance and support a rehabilitation programme [13].

TCM approach

Needling GB 41 and TE 5 bilaterally would be helpful in opening the Dai Mai and Yang Wei Mai and encouraging the descent of Yang energy. The Yang Wei Mai is considered as a secondary vessel to the Urinary Bladder meridian and is described as a network winding around the body, keeping the muscles tight [14]. Alternatively the Du and Yang Chiao Mai meridians could be used, associated with the central nervous system as they are. Use SI 3 and BL 62 bilaterally to open this pairing.

Part 3 Spinal cord stroke

Aetiology

Spinal cord infarction is usually caused by arteriosclerosis of the major arteries of the spinal cord. Other causes include embolism, acute systemic hypotension, aortic pathology or associated with spinal or aortic surgery [15]. Spinal cord haemorrhage may be caused by coagulopathies, trauma or vascular malformations such as spinal artery aneurysms or dural arteriovenous malformation [16].

Clinical presentation

Patients usually present with sudden onset of sharp spinal pain associated with weakness, sensory disturbance, loss of deep tendon reflexes and sphincter disturbance [18]. Presentation will be determined by spinal level involved. Most strokes affect the thoracic or thoracolumbar regions and will result in lower-limb weakness. Less commonly the cervical spinal cord is affected and this would result in weakness and sensory changes in all four limbs.

Prognosis

Recovery depends on the degree of spinal cord damage, as indicated by initial neurological examination. Presence of proprioceptive deficit, walking impairment or bladder dysfunction at outset is associated with poorer long-term outcome [18]. Some authors suggest that female sex and advanced age are negative indicators for recovery [15, 17]. A long-term follow-up of 57 patients with spinal cord infarction showed that 41% of patients were fully ambulant, 30% were able to walk with walking aids and 20% were wheelchair-dependent [17]. Pain is often problematic in the longer term.

[1] The University of Alabama National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. http://www.sci-info-pages.com/facts.html, 2002. Available online at: [Accessed 24 November 2009]

[2] American Spinal Injuries Association. International Standards for Functional Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Chicago: ASIA, 1992.

[3] Tederko P., Krasuski M., Kiwerski J., et al. Strategies for neuroprotection following spinal cord injury. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2009;11(2):103-110.

[4] Paddison F., Middleton F. Spinal cord injury. In: Stokes M., editor. Physical Management in Neurological Rehabilitation. Edinburgh: Elsevier Mosby; 2004:125-152.

[5] Nayak S., Shiflett S.C., Schoenberger N.E., et al. Is acupuncture effective in treating chronic pain after spinal column injury? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(11):1578-1586.

[6] Nayak S., Matheis R.J., Agostinelli S., et al. The use of complementary and alternative therapies for chronic pain following spinal cord injury: a pilot survey. J Spinal Cord Med. 2001;24(1):54-62.

[7] Averill A., Cotter A.C., Nayak S., et al. Blood pressure response to acupuncture in a population at risk for autonomic dysreflexia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(11):1494-1497.

[8] Cheng P.T., Wong M.K., Chang P.L. A therapeutic trial of acupuncture in neurogenic bladder of spinal cord injured patients – a preliminary report. Spinal Cord. 1998;36(37):476-480.

[9] Kong Y., Ren X., Lu S. High Paraplegia. The acupuncture treatment for paralysis. Beijing: Science Press, 1996;191-192.

[10] Maciocia G. The Practice of Chinese Medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1994.

[11] Jeffery D.R., Mandler R.N., Davis L.E. Transverse myelitis: retrospective analysis of 33 cases, with differentiation of cases associated with multiple sclerosis and parainfectious events. Arch Neurol. 1993;50(5):532-535.

[12] Berman M., Feldman S., Alter M., et al. Acute transverse myelitis: incidence and etiologic considerations. Neurology. 1981;8:966-971.

[13] Vaghela S.A., Donnellan C. Acupuncture for back pain, knee pain and insomnia in transverse myelitis – a case report. Acupuncture Med. 2008;26(3):188-192.

[14] Hopwood V. The extra meridians – the deepest level. Acupuncture in Physiotherapy. Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann, 2004;73-88.

[15] Salvador de la Barrera S., Barca-Buyo A., Montoto-Marques A., et al. Spinal cord infarction: prognosis and recovery in a series of 36 patients. Spinal Cord. 2001;39(10):520-525.

[16] Kim J.S., Lee S.H. Spontaneous spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage with spontaneous resolution. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009;45(4):253-255.

[17] Nedeltchev K., Loher T.J., Stepper F., et al. Long-term outcome of acute spinal cord ischemia syndrome. Stroke. 2004;35(2):560-565.

[18] Masson C., Pruvo J.P., Meder J.F., et al. Spinal cord infarction: clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings and short term outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(10):1431-1435.