Spinal Cord Imaging Techniques

Pediatric spinal cord imaging is a complex and interesting area that relies heavily on ultrasound in infants younger than 6 months of age and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) thereafter.1,2 Other imaging modalities such as plain radiography, myelography, computed tomography (CT), and nuclear scintigraphy serve a limited role but can provide useful adjunctive information in cases with a specific question.

Plain Radiography

Radiographic spine series typically include frontal and lateral radiographs of the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar region. Additional oblique radiographs may be added depending on the clinical indication. Plain radiographs have limited utility as a primary imaging tool in the evaluation of spinal cord but may demonstrate indirect evidence of underlying cord abnormalities and prompt performance of additional cross-sectional imaging. Nowhere else is this more true than in the setting of acute trauma.3 Although some studies have concluded that CT should be the initial study in acute trauma screening, radiography continues to be the mainstay for screening patients with trauma. Radiography also may be performed to screen older children with various spine-related complaints such as chronic back pain and torticollis. Subtle findings such as posterior vertebral body scalloping, widening of the neural foramina, or widening of the central canal may suggest underlying pathology (Fig. 41-1).4

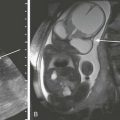

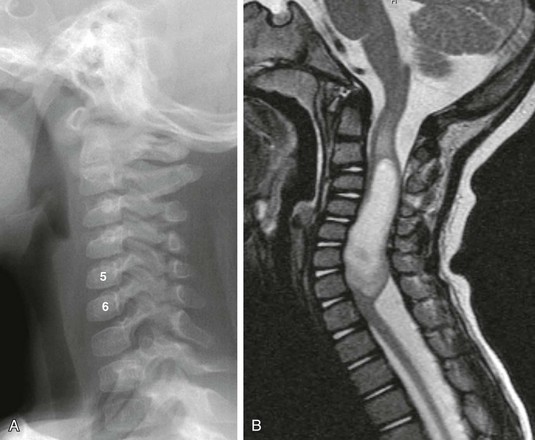

Figure 41-1 A cervical cord astrocytoma on a plain radiograph and magnetic resonance imaging in a 1-year-old girl with persistent torticollis.

A, A lateral cervical spine radiograph shows subtle posterior vertebral body scalloping causing C5 and C6 to take on an abnormal square shape compared with the normal adjacent rectangular vertebral bodies. B, A sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image confirms expansion of the cervical spinal canal because of a T2-hyperintense mass within the cervical cord. Note T2 bright cord edema above and below the mass.

Contrast Radiography

Contrast radiography is a term that includes angiography with biplane and triplane fluoroscopy and conventional myelography. As with plain radiography, contrast radiography has a limited role in the evaluation of spinal cord pathology. Largely, conventional myelography has been supplanted by MRI. CT myelography is useful in rare, specific clinical circumstances such as when patients cannot undergo MRI because of an implanted prosthesis, for example, cochlear implants or pacemakers.5 In such patients, myelography with or without CT can provide useful information about the spinal cord and thecal sac.

The role of conventional angiography in pediatric spinal imaging is as a secondary or tertiary modality to define vascular anatomy in preparation for treatment of dural fistulas and arteriovenous malformations, both of which are extremely rare in children.2

Computed Tomography

Like plain and contrast radiology, CT plays a limited role in direct spinal cord imaging. However, CT has the advantages of speed, availability, improved contrast resolution compared with radiography, limited operator independence, and the capability for multiplanar and three-dimensional reformations. It provides superior sensitivity and specificity in delineating osseous anomalies compared with other modalities and can indicate the need for additional spinal cord imaging (Fig. 41-2).3 Finally, as previously stated, CT and CT myelography can be performed in children who are unable to undergo MRI, thus allowing identification and characterization of mass lesions, calcifications, and areas of hemorrhage.5

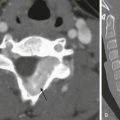

Figure 41-2 An epidural hematoma on computed tomography (CT) in a 15-year-old athlete with sudden arm pain and weakness.

A sagittal cervical spine CT image demonstrates a posterior hyperattenuated fluid collection (asterisk) compressing the spinal cord from C3 to C6. Magnetic resonance imaging (not shown) was obtained for further evaluation and followed by surgical drainage.

Ultrasound

Ultrasonography is a well-established method for evaluation of the neonatal spinal canal and its contents.1,6 The predominately cartilaginous and incompletely ossified spinal arches in infants serve as a superb acoustic window for transmission of the ultrasound beam. However, with progressive ossification, the acoustic window diminishes, allowing limited visualization of the spinal cord between the spinous processes.6 Although this limited acoustic window persists into adulthood, the spinal cord becomes difficult to adequately visualize on a routine basis in infants older than 6 months of age.1

Spinal ultrasound is performed with a high-frequency 7- to 12-MHz linear-array transducer or 8- to 10-MHz curved-array transducer.1 Newborns undergo imaging while prone in the longitudinal (sagittal) and transverse (axial) planes from the craniocervical junction through the conus medullaris and cauda equina (Fig. 41-3). Paramedian scanning may be useful in some patients with partially ossified vertebra.1 The vertebral bodies are carefully numbered by counting down from either the lowest rib and/or the craniocervical junction, and numbering is confirmed by counting up from the lumbosacral junction.1,7 This dual technique of numbering allows one to avoid misdiagnosing a low-lying, possibly tethered spinal cord. Real-time cine loops are obtained routinely as part of the examination in order to demonstrate the normal rhythmic movement of the cauda equina nerve roots during the cardiac cycle.1

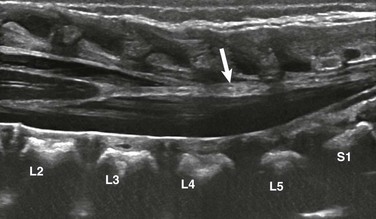

Figure 41-3 Fatty filum on ultrasound in a neonate with VATER syndrome.

A longitudinal sonogram reveals a normally positioned conus medullaris at L2-L3. Focal hyperechoic fat within the filum terminale (arrow) is noted. The child had normal development at 2 years of age.

Indications for spine ultrasound include screening for dysraphism and low conus position (possible tethered cord) in newborns with multiple congenital anomalies, as well as evaluation of midline dimples located above the gluteal crease more than 2.5 cm from the anus; dimples with associated skin stigmata (e.g., a hairy patch, hemangioma, pigmented area, skin tag, or tail); and deep dimples in which the bottom cannot be visualized on physical examination.7

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Overall, MRI is the primary modality for imaging the pediatric spinal cord because of its superior tissue contrast characteristics.2 MRI not only affords detailed evaluation of the spinal cord but also provides assessment of the surrounding soft tissues and osseous structures. Additional evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid flow characteristics are possible with phase contrast cerebrospinal fluid cine imaging, which most often is used to assess obstruction by Chiari 1 malformations at the craniocervical junction8 (Fig. 41-4). Bone marrow changes in a variety of disorders also may be assessed with conventional T1- and T2-weighted sequences.4,9 Lastly, MRI can be used as a secondary or tertiary modality for defining abnormalities identified on prenatal or antenatal ultrasonography, conventional radiography, and CT.2,4

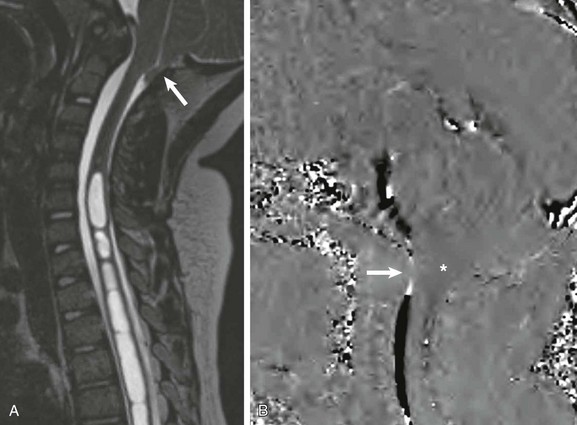

Figure 41-4 A Chiari 1 malformation on magnetic resonance imaging with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cine in a 6-year-old boy with levothoracic scoliosis.

A, A sagittal isometric heavily T2-weighted image reconstructed along the scoliotic curve shows the cerebellar tonsils extending into the posterior aspect of the upper cervical spinal canal (arrow) and a large multiseptated cervicothoracic syrinx. B, A phase-contrast CSF cine (velocity encoded to 5 cm/s) image reveals decreased flow across the foramen magnum (arrow) and slight cerebellar tonsil motion (asterisk).

Indications

The indications for spinal MRI in the pediatric population are numerous. Some of the more common indications include evaluation of known or suspected masses, inflammatory processes, posttraumatic spinal injuries, metastatic spread of an intracranial primary neoplasm, characterization of spinal dysraphisms, and dimples draining fluid.2,4,10

Pediatric Imaging Challenges

MRI is technically the most complicated of all modalities used in pediatric spine assessment. It is particularly challenging when performed in infants, neonates, and younger children who often are unwilling or unable to cooperate for the entire examination. In these patients, it is crucial to properly use methods to control patient motion, such as swaddling, sleep deprivation, and sedation, to avoid diminished image quality.2 Various sedation techniques have been used over the years, ranging from oral and intravenous drugs administered by the attending radiologist to general anesthesia performed by the anesthesiologist. No single recipe works for all patients and in all circumstances. Thus the sedation approach that is used will depend on the resources available at the institution performing the examination.

To produce high-quality magnetic resonance (MR) spinal examinations in children, various technical challenges must be overcome. Because of the small spinal cord volume, a smaller field of view and higher imaging matrix with thin sections and decreased or no interslice gap must be used.11,12 Because adjusting these technical parameters will result in a reduction of the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), an increased number of excitations and thus longer imaging time is mandated. With longer imaging times, patient and physiologic motion become more of an issue, even with proper sedation. Technical advances useful in overcoming this issue include application of flow-compensation (gradient moment nulling), respiratory gating, and saturation bands.11,13

High Field Strength MRI

With the increased utilization of 3-Tesla (T) MRI scanners, the inherent signal-to-noise issues encountered at 1.5 T may be overcome by using a higher field strength. When using the same scanning parameters, 3 T provides superior image quality and detail compared with 1.5 T.14 The improved image detail possible at 3 T is a direct result of the higher SNR compared with the lower field strength. The surplus of SNR can also be used in children to decrease imaging times without changing image quality, thus reducing sedation times and increasing MRI throughput.13,14

Although it is useful in the spine, high field strength MRI is not without its own limitations, including increased magnetic susceptibility artifact, increased chemical shift artifact, and increased specific absorption rate.13,14 Higher field strengths markedly increase magnetic susceptibility artifact from metallic objects, as well as from tissue-bone and tissue-air interfaces. This effect can be compensated for, to some degree, by increasing the band width. Chemical shift artifacts also increase with increasing field strength, degrading standard spin echo images. This effect too can be compensated for by increasing the bandwidth, but at a cost of decreasing SNR. Finally, the increased specific absorption rate at higher field strength is a potential limiting factor at 3 T, although standard specific absorption rate values are rarely exceeded with routine imaging.14

Coil Selection

Surface coils are the standard practice, and higher channel numbers will provide increasing image quality. Only coils directly aligned with the region of interest should be turned on during scanning.15

Mri Parameters

Standard pediatric spinal MR sequences include, at a minimum, axial and sagittal T1 imaging and axial and sagittal T2 imaging with or without fat saturation.2,10 Coronal T2 sequences often are routinely performed, as they are particularly helpful in patients with scoliosis or paraspinal lesions. Isometric sequences allow volumetric imaging with curved reformations in the evaluation of severely scoliotic patients.16,17 Recently, diffusion weighted imaging (e-Fig. 41-5) has been used in the spine to differentiate dermoids and epidermoids from arachnoid cysts.5,11 Although use of diffusion tensor imaging has been popular in the pediatric brain, thus far it has not been used routinely in the pediatric spine.

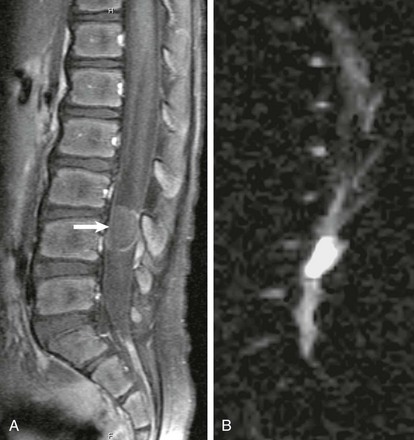

e-Figure 41-5 An epidermoid on magnetic resonance imaging in a 6-year-old boy with back pain.

A, A sagittal fat-suppressed, contrast-enhanced, T1-weighted image identifies a well-circumscribed mass with minimal peripheral enhancement in the spinal canal posterior to L4 (arrow). B, A sagittal diffusion-weighted image shows hyperintense, restricted diffusivity within the mass.

Contrast Material

Gadolinium contrast enhancement occurs in some lesions, allowing them to be better visualized as a result of increased tissue contrast.18 Although many lesions, such as cord transection and infarction, can be fully evaluated without the use of a contrast agent, intravenous gadolinium is administered routinely when assessing neoplastic and inflammatory processes.2,10 In addition, it is variably given on a case by case basis, depending on the indication for the examination and the unenhanced MRI findings.

Nuclear Scintigraphy

Nuclear scintigraphy has limited use in the evaluation of the pediatric spinal cord and surrounding structures. Other than very rare use in assessment of shunt patency and cerebral spinal fluid leaks, it occasionally is used to evaluate adjacent osseous structures, for example, gallium scanning for vertebral osteomyelitis and bone scanning for metastatic disease. However, with the increasing utilization of high-resolution positron emission tomography with 18F-2-fluorodeoxyglucose, positron emission tomography imaging may develop a larger role in the evaluation of spinal cord disorders, particularly in tumors in which treatment response can be assessed.19

Lowe, LH, Johanek, AJ, Moore, CW. Sonography of the neonatal spine: part 1, normal anatomy, imaging pitfalls, and variations that may simulate disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(3):733–738.

Lowe, LH, Johanek, AJ, Moore, CW. Sonography of the neonatal spine: part 2. Spinal disorders. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(3):739–744.

Vertinsky, AT, Krasnokutsky, MV, Augustin, M, et al. Cutting-edge imaging of the spine. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2007;17(1):117–136.

References

1. Unsinn, KM, Geley, T, Freund, MC, et al. US of the spinal cord in newborns: spectrum of normal findings, variants, congenital anomalies, and acquired diseases. Radiographics. 2000;20(4):923–938.

2. Byrd, SE, Darling, CF, McLone, DG, et al. MR imaging of the pediatric spine. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 1996;4(4):797–833.

3. Lammertse, D, Dungan, D, Dreisbach, J, et al. Neuroimaging in traumatic spinal cord injury: an evidence-based review for clinical practice and research. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30(3):205–214.

4. Koeller, KK, Rosenblum, RS, Morrison, AL. Neoplasms of the spinal cord and filum terminale: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20(6):1721–1749.

5. Khosla, A, Wippold, FJ, 2nd. CT myelography and MR imaging of extramedullary cysts of the spinal canal in adult and pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178(1):201–207.

6. Dick, EA, Patel, K, Owens, CM, et al. Spinal ultrasound in infants. Br J Radiol. 2002;75(892):384–392.

7. Kriss, VM, Desai, NS. Occult spinal dysraphism in neonates: assessment of high-risk cutaneous stigmata on sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171(6):1687–1692.

8. Sharma, A, Parsons, MS, Pilgram, TK. Balanced steady-state free-precession MR imaging for measuring pulsatile motion of cerebellar tonsils during the cardiac cycle: a reliability study. Neuroradiology. 2012;54(2):133–138.

9. Tall, MA, Thompson, AK, Vertinsky, T, et al. MR imaging of the spinal bone marrow. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2007;15(2):175–198. [vi].

10. Walker, HS, Dietrich, RB, Flannigan, BD, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pediatric spine. Radiographics. 1987;7(6):1129–1152.

11. Robertson, RL, Maier, SE, Mulkern, RV, et al. MR line-scan diffusion imaging of the spinal cord in children. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(7):1344–1348.

12. Bammer, R, Fazekas, F. Diffusion imaging of the human spinal cord and the vertebral column. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;14(6):461–476.

13. Vargas, MI, Delavelle, J, Kohler, R, et al. Brain and spine MRI artifacts at 3Tesla. J Neuroradiol. 2009;36(2):74–81.

14. Phalke, VV, Gujar, S, Quint, DJ. Comparison of 3.0 T versus 1.5 T MR: imaging of the spine. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2006;16(2):241–248. [ix].

15. Moriya, S, Miki, Y, Yokobayashi, T, et al. Optimization of the number of selectable channels for spine phased array coils for transverse imaging. Jpn J Radiol. 2011;29(3):166–170.

16. Weiss, KL, Sun, D, Weiss, JL. Pediatric MR imaging with automated spine survey iterative scan technique (ASSIST). AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(4):821–824.

17. Rumboldt, Z, Marotti, M. Magnetization transfer, HASTE, and FLAIR imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2003;11(3):471–492.

18. Hahn, G, Sorge, I, Gruhn, B, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of gadobutrol-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in pediatric patients. Invest Radiol. 2009;44(12):776–783.

19. Kamoto, Y, Sadato, N, Yonekura, Y, et al. Visualization of the cervical spinal cord with FDG and high-resolution PET. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22(3):487–491.