15 Spinal cord

Ascending pathways

General Features

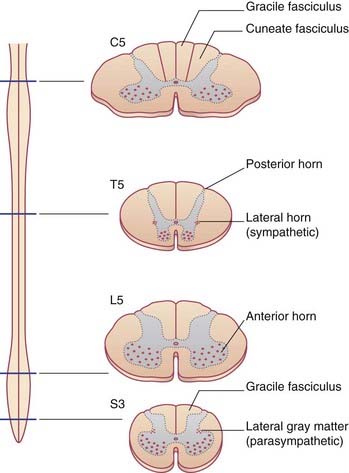

The arrangement of gray and white matter at different levels of the spinal cord is shown in Figure 15.1. The cervical and lumbosacral enlargements are produced by expansions of the gray matter required to service innervation of the limbs. White matter is most abundant in the upper reaches of the cord, which contain the sensory and motor pathways serving all four limbs. In the posterior funiculus, e.g., the gracile fasciculus carries information from the lower limb and is present at cervical as well as lumbosacral segmental levels, whereas the cuneate fasciculus carries information from the upper limb and is not seen at lumbar level.

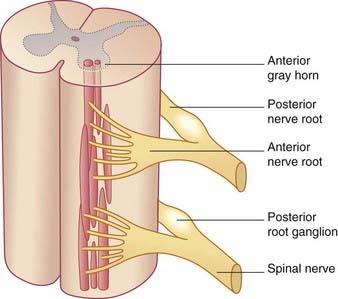

Although it is convenient to refer to different levels of the spinal cord in terms of numbered segments, corresponding to the sites of attachment of the paired nerve roots, the cord shows no evidence of segmentation internally. The nuclear groups seen in transverse sections are in reality cell columns, most of them spanning several segments (Figure 15.2).

Types of spinal neurons

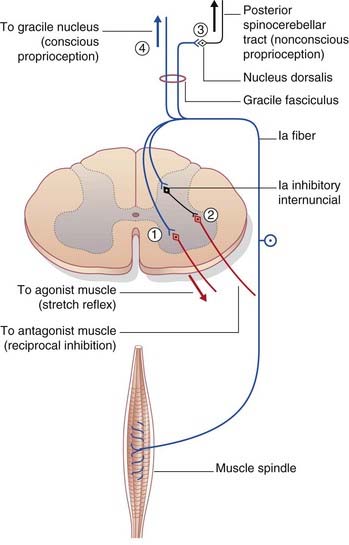

Spinal reflex arcs originating in muscle spindles and tendon organs have been described in Chapter 10, and the withdrawal reflex in Chapter 14.

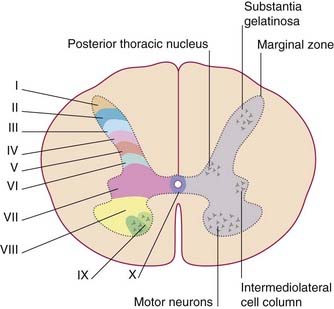

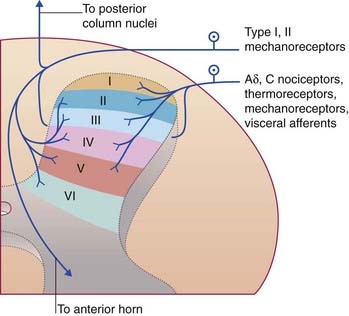

In thick sections of the spinal cord, the nerve cells exhibit a laminar (layered) arrangement. True lamination is confined to the posterior horn (Figure 15.3), but 10 laminae of Rexed have been defined in the gray matter as a whole in order to correlate findings from animal research in different laboratories.

Spinal ganglia

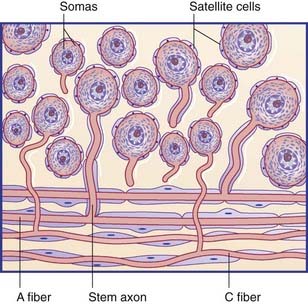

The spinal or posterior (dorsal) root ganglia are located in the intervertebral foramina, where the anterior and posterior roots come together to form the spinal nerves. Thoracic ganglia contain about 50,0000 unipolar neurons, and those serving the limbs contain about 100,000. The individual ganglion cells are invested with modified Schwann cells called satellite cells (Figure 15.4). The common stem axon of each cell bifurcates, sending a centrifugal process into one or other ramus of the spinal nerve (or into the recurrent branch) and a centripetal (‘center-seeking’) process into the spinal cord. Following stimulation of the peripheral sensory receptors, trains of nerve impulses traverse the point of bifurcation without interruption, although the cell body is also depolarized. The initial segment of the stem axon does not normally generate impulses but it may do so if the adjacent part of the posterior root is compressed, e.g. by a prolapsed intervertebral disc.

Traditionally, the centripetal axons of all spinal ganglion cells have been thought to enter posterior nerve roots. It is now known that many visceral afferents (in particular) enter the cord by way of ventral roots and work their way to the posterior gray horn (Ch. 13). This feature accounts for the frequent failure of posterior rhizotomy (surgical section of posterior roots) to relieve pain originating from intra-abdominal cancer.

Ascending Sensory Pathways

Categories of sensation

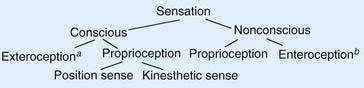

In accordance with the flowchart in Figure 15.6, neurologists speak of two kinds of sensation, conscious and nonconscious (unconscious). Conscious sensations are perceived at the level of the cerebral cortex. Nonconscious sensations are not perceived; they have reference to the cerebellum (see later).

Sensory testing

Routine assessment of somatic exteroceptive sensation includes tests for:

Passive tests of conscious proprioception include:

Somatic Sensory Pathways

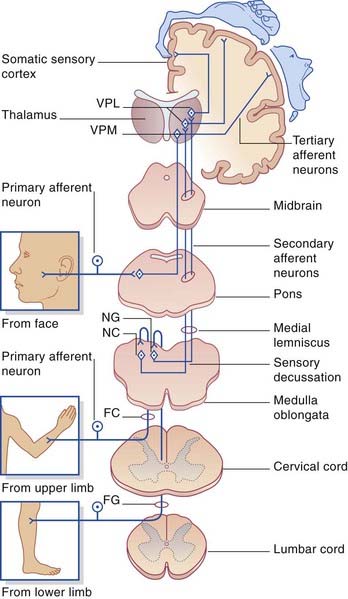

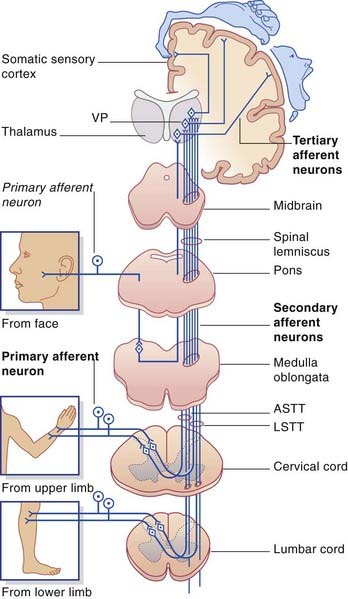

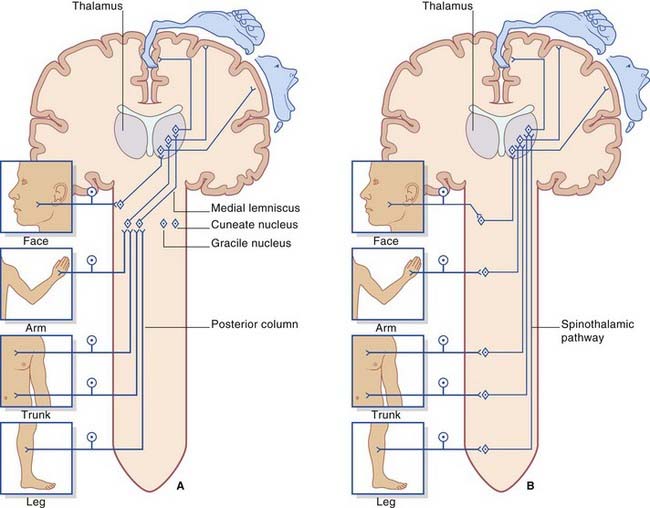

Two major pathways are involved in somatic sensory perception. They are the posterior column–medial lemniscal pathway and the spinothalamic (anterolateral) pathway. They have the following features in common (Figure 15.7):

Figure 15.7 Basic plans of (A) posterior column–medial lemniscal pathway; (B) spinothalamic pathway.

Posterior (dorsal) column–medial lemniscal pathway

The first-order afferents include the largest somas in the posterior root ganglia. Their peripheral processes collectively receive information from the largest sensory receptors: Meissner’s and Pacinian corpuscles, Ruffini endings and Merkel cell–neurite complexes, neuromuscular spindles, and Golgi tendon organs. The centripetal processes from cells supplying the lower limb and lower trunk give branches to the gray matter before ascending as the gracile fasciculus (fasciculus gracilis) to reach the gracile nucleus in the medulla oblongata (Figure 15.8). The corresponding collaterals from the upper limb and upper trunk run in the cuneate fasciculus (fasciculus cuneatus) to reach the cuneate nucleus.

The third-order afferents project from the thalamus to the somatic sensory cortex (see Ch. 27 for details).

Functions

In humans, disturbance of posterior column function is most often observed in association with demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis. The classic symptom is known as sensory ataxia. This term signifies a movement disorder resulting from sensory impairment, in contrast to cerebellar ataxia, in which a movement disorder results from a lesion within the motor system. The patient with a severe sensory ataxia can stand unsupported only with the feet well apart and with the gaze directed downward to include the feet. The gait is broad-based, with a stamping action that maximizes any conscious proprioceptive function that remains (Figure 15.9).

Note: Romberg’s sign may be elicited in patients suffering from vestibular disorders (Ch. 19). In cerebellar disorders, there may be instability of station whether the eyes are open or closed (Ch. 25).

Spinothalamic pathway

The spinothalamic pathway consists of second-order sensory neurons projecting from laminae I–II, IV–V of the posterior gray horn to the contralateral thalamus (Figure 15.10). The cells of origin receive excitatory and inhibitory synapses from neurons of the substantia gelatinosa; these have important ‘gating’ (modulatory) effects on sensory transmission, as explained in Chapter 24.

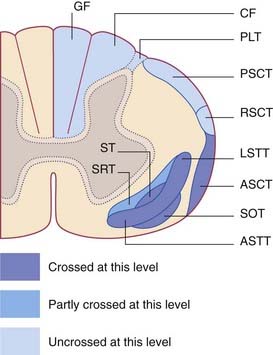

The axons of the spinothalamic pathway cross the midline in the anterior commissure at all segmental levels. Having crossed, they run upward in the anterolateral part of the cord. This anterolateral pathway (as it is usually called) is divisible into an anterior spinothalamic tract located in the anterior funiculus and a lateral spinothalamic tract located in the lateral funiculus. The two tracts merge in the brainstem as the spinal lemniscus. The spinal lemniscus is joined by trigeminal afferents from the head region, and it accompanies the medial lemniscus to the ventral posterior nucleus of the thalamus, terminating immediately behind the medial lemniscus. Third-order sensory neurons project from the thalamus to the somatic sensory cortex (Ch. 27).

Functions

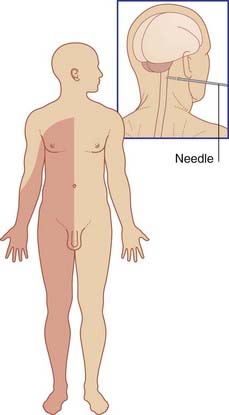

The functions of the spinothalamic pathway have been elucidated by the procedure known as cordotomy, whereby the spinothalamic pathway is interrupted on one or both sides for the relief of intractable pain. For a percutaneous cordotomy, the patient is sedated and a needle is passed between the atlas and the axis, into the subarachnoid space. Under radiological guidance, the needle tip is advanced into the anterolateral region of the cord. A stimulating electrode is passed through the needle. If the placement is correct, a mild current will elicit paresthesia (tingling) on the opposite side of the body. The anterolateral pathway is then destroyed electrolytically. Afterwards, the patient is insensitive to pinprick, heat, or cold applied to the opposite side (Figure 15.11). Sensitivity to touch is reduced. The effect commences several segments below the level of the procedure because of the oblique passage of spinothalamic fibers across the white commissure.

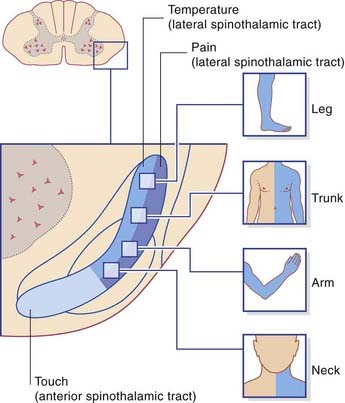

The internal anatomy of the human spinothalamic pathway has been worked out from postoperative sensory testing and is shown in Figure 15.12. The picture is one of modality segregation. The lateral spinothalamic tract mediates noxious and thermal sensations separately, and the anterior spinothalamic tract mediates touch. The lateral tract is somatotopically arranged, the neck being represented at the front and the leg at the back. The anterior tract is also somatotopic.

A rare but classical condition illustrating dissociated sensory loss is illustrated in Clinical Panel 15.1.

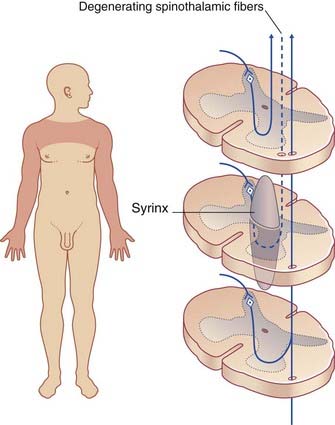

Clinical Panel 15.1 Syringomyelia

Syringomyelia is a disorder of uncertain etiology, characterized by development of a syrinx (fusiform cyst) in or beside the central canal, usually in the cervical region (Figure CP 15.1.1). Initial symptoms arise from obliteration of spinothalamic fibers decussating in the white commissure.

Spinoreticular tracts

The spinoreticular tracts are the phylogenetically oldest somatosensory pathways. The reticular formation of the brainstem has scant regard for the midline, being often bilaterally distributed in terms of its ascending and descending connections. Spinoreticular fibers originate in laminae V–VII and accompany the spinothalamic pathway as far as the brainstem (Figure 15.13). Postmortem studies of nerve fiber degeneration following cordotomy procedures indicate that at least half of the spinoreticular fibers may be uncrossed. Accurate estimations based on axonal degeneration are difficult because some spinothalamic fibers give off collaterals to the reticular formation as they pass by.

The spinoreticular tracts terminate at all levels of the brainstem and they are not somatotopically arranged. Impulse traffic is continued rostrally to the thalamus in the ascending reticular activating system (Ch. 24). Briefly, the spinoreticular system has two interrelated functions:

Spinocerebellar pathways

Four fiber tracts run from the spinal cord to the cerebellum. They are:

Nonconscious proprioception

The posterior spinocerebellar tract originates in the posterior thoracic nucleus (formerly, dorsal nucleus or Clarke’s column) in lamina VII at the base of the posterior gray horn (Figure 15.3). The nucleus extends from T1 through L1 segmental levels and the primary afferents from the lower limb enter the gracile fasciculus to reach it (Figure 15.14). It receives primary afferents of all kinds from the muscles and joints, including an intense input from muscle spindle primaries. It also receives collaterals from cutaneous sensory neurons. The fibers of the posterior spinocerebellar tract are the largest in the entire CNS, measuring 20 µm in external diameter. Very fast conduction is required to keep the cerebellum informed about ongoing movements. The tract ascends close to the surface of the cord (Figure 15.14) and enters the inferior cerebellar peduncle.

Information from reflex arcs

From the lower half of the cord, the pathway is the anterior (ventral) spinocerebellar tract (Figure 15.13). The component fibers cross initially and run close to the surface as far as the midbrain. They then turn into the superior cerebellar peduncle and re-cross within the cerebellar white matter.

From the upper half of the cord, the rostral spinocerebellar tract (Figure 15.13) ascends without crossing and enters (mainly) the inferior cerebellar peduncle.

Other Ascending Pathways

The spinotectal tract runs alongside the spinothalamic pathway (Figure 15.13) which it resembles in its origin and functional composition. It ends in the superior colliculus, where it joins crossed visual inputs involved in turning the eyes/head/trunk toward sources of sensory stimulation (visuospinal reflex).

The spino-olivary tract sends tactile information to the inferior olivary nucleus in the medulla oblongata. The inferior olivary nucleus has an important function in motor learning through its action on the contralateral cerebellar cortex (Ch. 25). Spino-olivary discharge can modify cerebellar activity in response to environmental change, for example while climbing a surprisingly steep stairway. This feature is called motor adaptation. On the other hand, learning to perform routine motor programs automatically is a function of the basal ganglia (Ch. 33).