Chapter 7 Spinal Column

Spinal Cord and Its Coverings

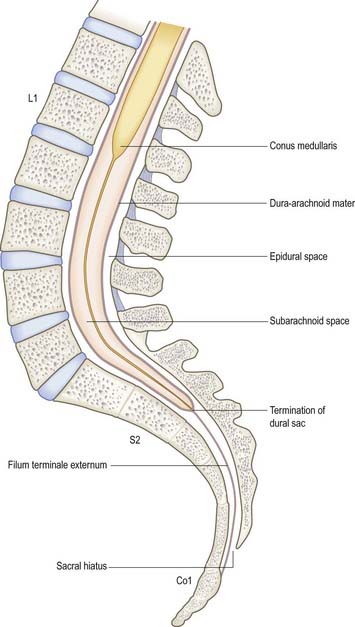

The surface relationships of the spinal cord and its coverings are of great clinical importance throughout life (Fig. 7.1).

Clinical Procedures

Access to Cerebrospinal Fluid

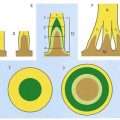

The safest approach to the CSF is to enter the lumbar cistern of the subarachnoid space in the midline, well below the level at which the spinal cord normally terminates (see Fig. 7.1). The fine needle employed is unlikely to damage the mobile nerve roots of the cauda equina. This procedure is called lumbar puncture. It is also possible to access the CSF by midline puncture of the cerebellomedullary cistern (cisterna magna); this is called cisternal puncture.

Lumbar Puncture: Adult

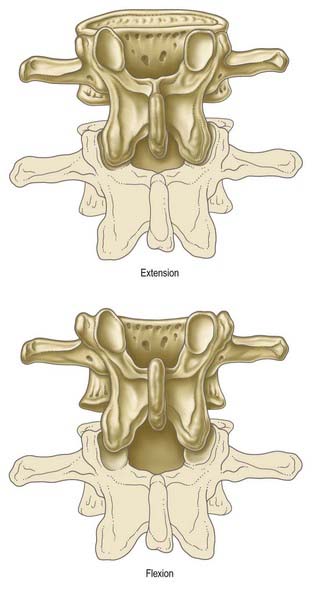

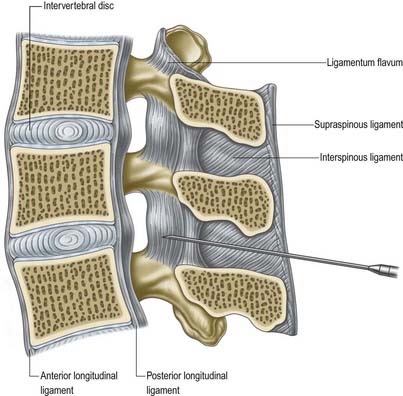

Lumbar puncture in the adult may be performed with the patient either sitting or lying on the side on a firm, flat surface. In each position, the lumbar spine must be flexed as far as possible to separate the vertebral spines maximally and expose the ligamentum flavum in the interlaminar window (Fig. 7.2). A line between the highest points of the iliac crests intersects the vertebral column just above the palpable spine of L4. With the spines now identified, the skin is anaesthetized and a needle is inserted between the spines of L3 and L4 (or L4 and L5). Exact identification of the level by palpation is difficult (Broadbent et al 2000). The soft tissues the needle will ultimately traverse should also be anaesthetized, but care should be taken to avoid injection of an excessive amount of local anaesthetic, which can compromise one’s appreciation of the structures being traversed. These include the subcutaneous fat and supraspinous and interspinous ligaments down to the ligamentum flavum itself. The lumbar puncture needle is then inserted in the midline or just to one side and angled in the horizontal and sagittal planes sufficiently to pierce the ligamentum flavum in or very near the midline (Fig. 7.3).There is a slight loss of resistance as the needle enters the epidural space, and careful advancement pierces the dura and arachnoid to release CSF.

Access to the Epidural Space

Caudal Epidural

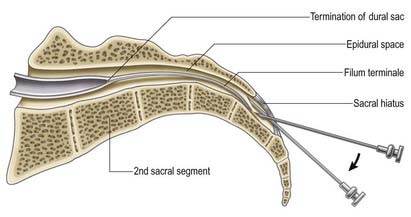

The route of access to the caudal epidural space is via the sacral hiatus. The space is thus entered below the level of termination of the dural sac (S2). With the patient in the lateral position or lying prone over a pelvic pillow, the sacral hiatus is identified by palpation of the sacral cornua (Fig. 7.4). These are felt at the upper end of the natal cleft approximately 5 cm above the tip of the coccyx. Alternatively, the sacral hiatus may be identified by constructing an equilateral triangle based on a line joining the posterior superior iliac spines: the inferior apex of this triangle overlies the hiatus. After local anaesthetic infiltration, a needle is introduced at a 45-degree angle to the skin to penetrate the posterior sacrococcygeal ligament and enter the sacral canal. Once the canal is entered, the hub of the needle is lowered so that the needle may pass along the canal (Fig. 7.5). If the needle is angled too obliquely it will strike bone; if it is placed too superficially it will lie outside the canal. The latter malposition can be confirmed by careful injection of air while palpating the skin over the lower sacrum.

Vertebral Column

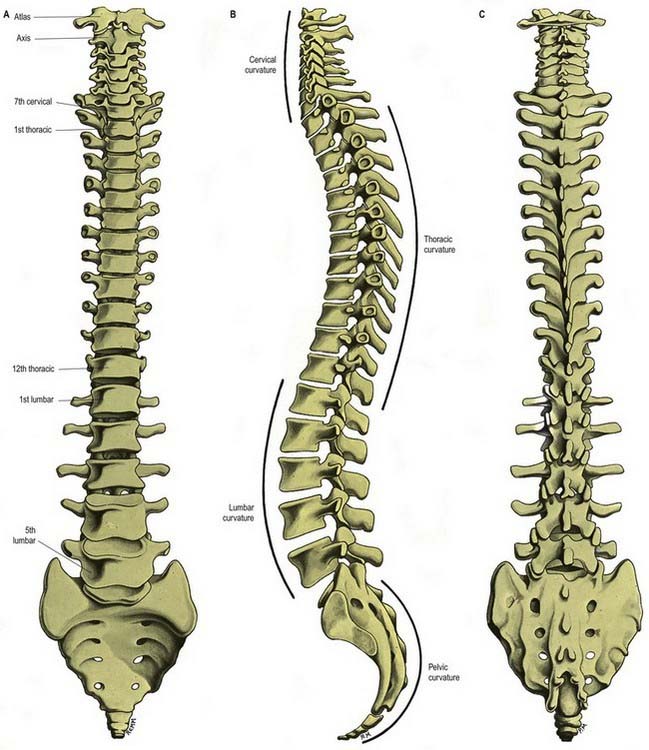

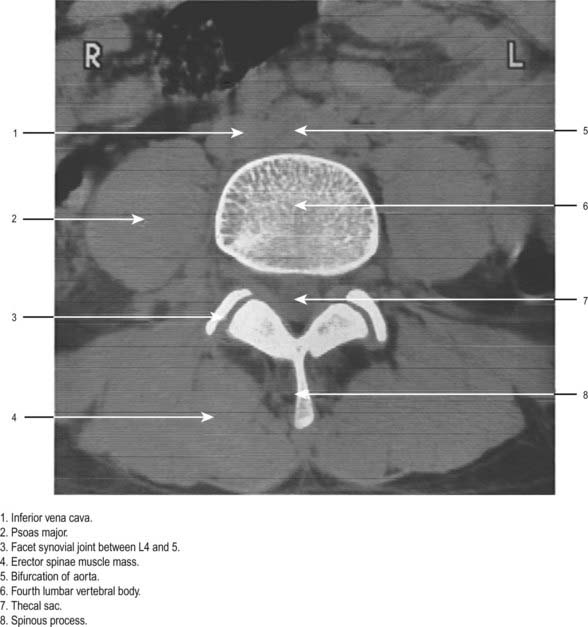

The vertebral column is a curved linkage of individual bones or vertebrae (Figs 7.6, 7.7). A continuous series of vertebral foramina runs through the articulated vertebrae posterior to their bodies and collectively constitutes the vertebral canal, which transmits and protects the spinal cord and nerve roots, their coverings and vasculature. A series of paired lateral intervertebral foramina transmit the spinal nerves and their associated vessels between adjacent vertebrae. The linkages between the vertebrae include cartilaginous interbody joints and paired synovial facet (zygapophyseal) joints (Fig. 7.8), together with a complex of ligaments and overlying muscles and fasciae. The muscles directly concerned with vertebral movements and attached to the column lie mainly posteriorly. Several large muscles producing major spinal movements lie distant from the column and have no direct attachment to it, such as the anterolateral abdominal wall musculature. The column as a whole receives its vascular supply and innervation according to the general anatomical principles considered later in this chapter.

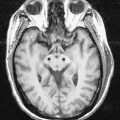

Fig. 7.7 A, Sagittal MRI of the thoracolumbosacral spine. B, Sagittal MRI of the cervicothoracic spine.

(Courtesy of Dr. Justin Lee, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London.)

Vertebral column morphology is influenced externally by mechanical and environmental factors and internally by genetic, metabolic and hormonal factors. These all affect its ability to react to the dynamic forces of everyday life, such as compression, traction and shear. These dynamic forces can vary in magnitude and are influenced by occupation, locomotion and posture.

Anterior Aspect

The anterior aspect of the column is formed by the anterior surfaces of the vertebral bodies and of the intervertebral discs (see Fig. 7.6A). It has important anatomical relations at all levels and should be considered in continuity. It forms part of several clinically significant junctional or transitional zones, including the prevertebral–retropharyngeal zone of the neck, the thoracic inlet, the diaphragm and the pelvic inlet. The anterior aspect of the column is covered centrally by the anterior longitudinal ligament, which forms a fascial plane with the prevertebral and endothoracic fascia and with the subperitoneal areolar tissue of the posterior abdominal wall. Infection and other pathological processes may spread along this fascial plane.

Lateral Aspect

The lateral aspect of the vertebral column is arbitrarily separated from the posterior by articular processes in the cervical and lumbar regions and by transverse processes in the thoracic region (see Fig. 7.6B). Anteriorly, it is formed by the sides of vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs. The oval intervertebral foramina, behind the bodies and between the pedicles, are smallest at the cervical and upper thoracic levels and progressively increase in size in the thoracic and upper lumbar regions. The lumbosacral (L5–S1) intervertebral foramen is the smallest of the lumbar foramina. The foramina permit communication between the lumen of the vertebral canal and the paravertebral soft tissues (a ‘paravertebral space’ is sometimes described), which may be important in the spread of tumours and other pathological processes. The lateral aspects of the column have important anatomical relations, some of which vary considerably between the two sides.

Posterior Aspect

The posterior aspect of the column is formed by the posterior surfaces of the laminae and spinous processes, their associated ligaments and the facet joints (see Fig. 7.6C). It is covered by the deep muscles of the back.

Curvatures

Neonatal Curvatures

In the neonate the vertebral column has no fixed curvatures. It is particularly flexible and, if dissected free from the body, can easily be bent (flexed or extended) into a perfect half circle. A slight sacral curvature may develop as the sacral vertebrae ossify and fuse. The thoracic part of the column is the first to develop a relatively fixed curvature, which is concave anteriorly. An infant can support its head at approximately 3 or 4 months, can sit upright at 9 months and commences walking between 12 and 15 months. These functional changes exert a major influence on the development of secondary curvatures in the vertebral column and changes in the proportional size of the vertebrae, particularly in the lumbar region. The secondary lumbar curvature becomes important in maintaining the centre of gravity of the trunk over the legs when walking starts; thus, changes in body proportions exert a major influence on the subsequent shape of curvatures in the vertebral column.

Adult Curvatures

The presence of these curvatures means that the cross-sectional profile of the trunk changes with the spinal level. The anteroposterior diameter of the thorax is much greater than that of the lower abdomen. In the normal vertebral column there are well-marked curvatures in the sagittal plane and no lateral curvatures other than in the upper thoracic region, where there is often a slight lateral curvature that is convex to the right in right-handed persons and to the left in left-handed persons. Compensatory lateral curvature may also develop to cope with pelvic obliquity, such as that imposed by unequal leg lengths. The sagittal curvatures are present in the cervical, thoracic, lumbar and pelvic regions (see Fig. 7.6). These curvatures developed with rounding of the thorax and pelvis as an adaptation to bipedal gait.

Vertebral Column in the Elderly

In the mid-lumbar region, the width of the vertebral body increases with age. In men, there is a relative decrease of posterior-to-anterior body height; in both sexes anterior height decreases relative to width. Twomey and coworkers (1983) observed a reduction in bone density of lumbar vertebral bodies with age, principally as a result of a reduction in transverse trabeculae (more marked in females owing to postmenopausal osteoporosis); this was associated with increased diameter and increasing concavity in the juxtadiscal surfaces (end-plates).

Other changes affect the vertebral bodies. Osteophytes (bony spurs) may form from the compact cortical bone on the anterior and lateral surfaces of the bodies. Although individual variations occur, these changes appear in most individuals from about age 20 years onward. They are most common on the anterior aspect of the body and never involve the ring epiphysis. Osteophytic spurs are frequently asymptomatic but may result in diminished movements within the spine.

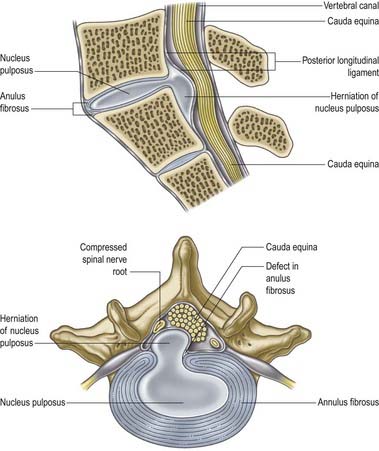

CASE 1 Acute Lumbar Disc Herniation

Discussion: This is a classic presentation of radicular pain (i.e. sciatica) secondary to an acute lateral intervertebral disc protrusion at L5–S1 (Fig. 7.9). Typically, there is narrowing of the intervertebral disc space at the involved segment. The herniated disc fragment can be identified by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Adams, Bogduk, Burton, Dolan, 2002Adams M.A. Bogduk N. Burton K. Dolan P. The Biomechanics of Back Pain. 2002. Churchill Livingstone. Edinburgh.

Bogduk N. Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum, third ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997.

Broadbent C.R., Maxwell W.E., Ferrie R., Wilson D.J., Gawne-Cain M., Russell R. Ability of anaesthetists to identify a marked lumbar interspace. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:1122-1126.

Denis, 1983Denis F. The three column spine and its significance in the classification of acute thoracolumbar spinal injuries. Spine. 8:1983;817-831.

Seminal paper for the understanding and classification of spinal instability.

Dvorák J., Vajda E.G., Grob D., Panjabi M.M. Normal motion of the lumbar spine related to age and gender. Eur. Spine J.. 1995;4:18-23.

Frobin W., Leivseth G., Biggeman M., Brinckmann P. Sagittal plane segmental motion of the cervical spine: a new precision measurement protocol and normal motion data of healthy adults. Clin. Biomech.. 2002;17:21-31.

MacLaughlin, Oldale, 1992MacLaughlin S.M. Oldale K.N.M. Vertebral body diameters and sex prediction. Ann. Hum. Biol.. 19:1992;285-293.

Describes the archaeological and forensic examination of skeletal material.

MacNab, McCulloch, 1990MacNab I. McCulloch J. Backache, second ed. 1990. Williams and Wilkins. Baltimore. Chapter 1.

McGregor A.H., McCarthy I.D., Hughes S.P.F. Motion characteristics of the lumbar spine in the normal population. Spine. 1995;20(22):2421-2428.

Newell, 1999Newell R.L.M. The spinal epidural space. Clin. Anat.. 12:1999;375-379.

Review of the morphological, developmental and topographical aspects of the spinal epidural space.

Ordway N.R., Seymour R., Donelson R.G., Hojnowski L., Lee E., Edwards T. Cervical sagittal range of motion using three methods. Spine. 1997;22:501-508.

Pearcy M., Protek I., Shepherd J. Three-dimensional X-ray analysis of normal movement in the lumbar spine. Spine. 1984;9:294-297.

Pearcy M., Tibrewal S.B. Axial rotation and lateral bending in the normal lumbar spine. Spine. 1984;9:582-587.

Taylor, Twomey, 1984Taylor J.R. Twomey L.T. Sexual dimorphism in human vertebral shape. J. Anat.. 138:1984;281-286.

Anthropometric and radiological studies of children and adolescents.

Trott P.H., Pearcy M.J., Ruston S.A., Fulton I., Brien C. Three-dimensional analysis of active cervical motion: the effect of age and gender. Clin. Biomech.. 1996;11:201-206.

Twomey L.T., Taylor J.R., Furniss B. Age changes in the bone density and structure of the lumbar vertebral column. J. Anat.. 1983;136:15-25.

White A.A., Panjabi M.M. Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, second ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1990.