Chapter 6 Spinal Accessory Nerve

Anatomy

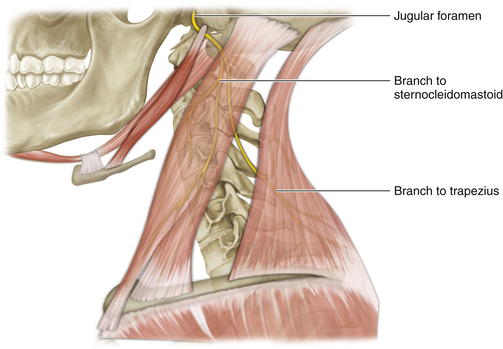

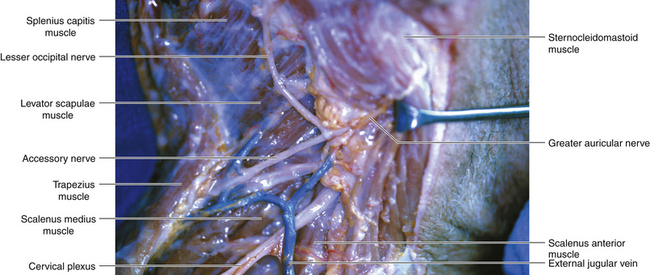

• The accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI) leaves the skull through the jugular foramen. Below this landmark the nerve is an immediate anterior relation of the transverse process of the atlas (Figure 6-1).

• The mastoid process is easily palpated, and if the surgeon drops a fingertip immediately below the mastoid a bony prominence may be felt. This is the transverse process of the atlas.

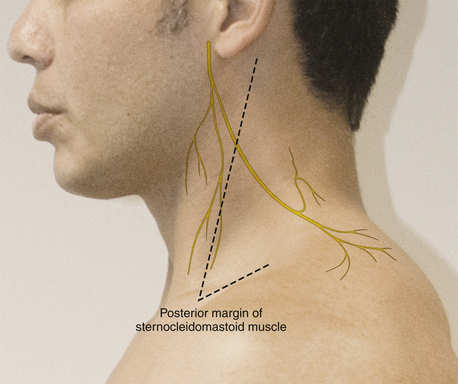

• A line drawn from the transverse process of the atlas to the point of the shoulder overlies the course of the accessory nerve when the neck is viewed from the side (Figure 6-2).

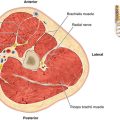

• The nerve runs between the heads of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) so that it appears to pierce the upper anterior border of that muscle. The sternocleidomastoid is supplied by the nerve before it appears at the posterior border of the muscle. This point is two thirds of the distance between the lower and upper attachments of the SCM.

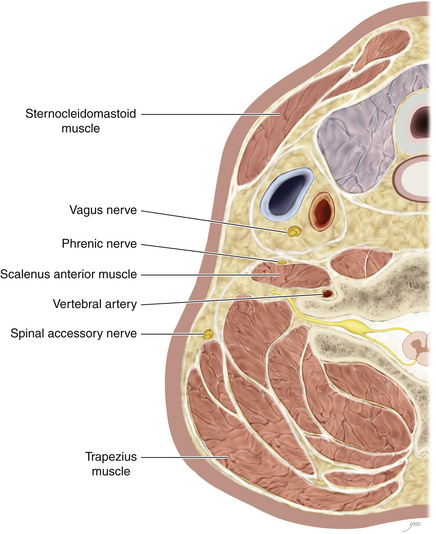

• As the nerve courses through the posterior triangle, en route to the trapezius, it is covered solely by fascia and skin (Figure 6-3).

• Lymph nodes are characteristically found immediately adjacent to the nerve. Adherence of the two structures may result from previous inflammation.

• The nerve breaks into numerous short branches that directly innervate the great trapezius muscle.

Adjacent Nerves

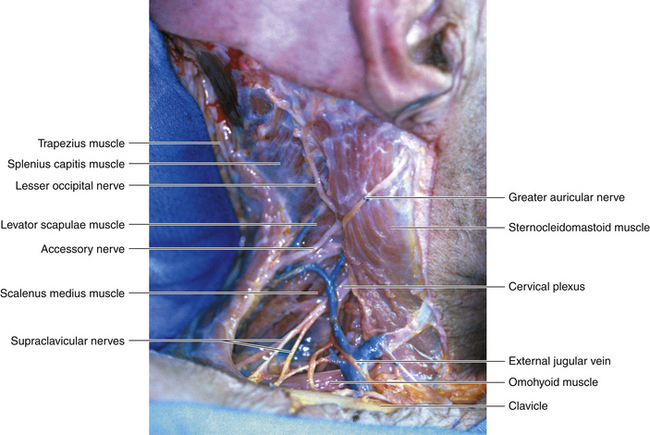

• The greater auricular nerve and other cutaneous branches of the cervical plexus, including the transverse cervical nerve, wrap around the posterior border of the SCM and are useful landmarks in finding the eleventh nerve at its point of egress from the SCM (Figure 6-4).

• The fifth cervical nerve is below the eleventh cranial nerve, and the surgeon should be conscious of their close relationship when operating on that proximal spinal nerve.

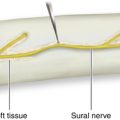

• Several nerves run parallel to the eleventh nerve over the floor of the posterior triangle. These are proprioceptive and sensory nerves (Figure 6-5).

Surgery

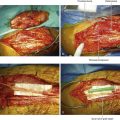

• It is usually convenient to add vertical limbs to the horizontal scar of a previous lymph node biopsy, thus creating a Z.

• Alternatively, an incision is made similar to that used for the exploration of the supraclavicular brachial plexus (Figure 6-6).

• The cervical plexus cutaneous nerves are seen as the posterior border of the SCM is cleared, and the surgeon must then identify the eleventh nerve.

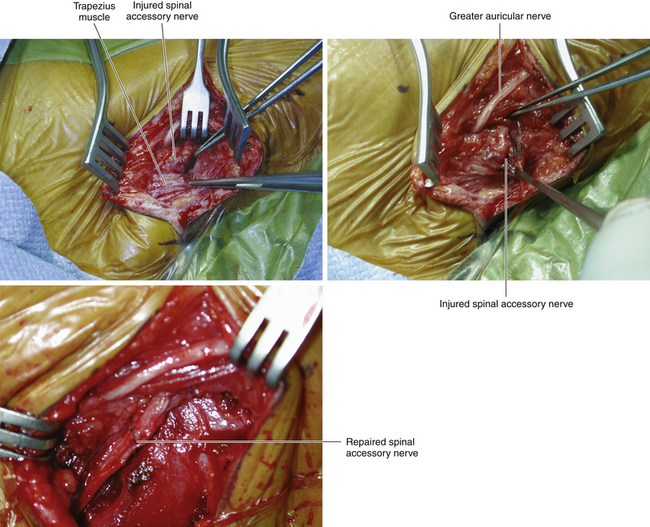

• No structure will present itself with XI written on it. Thus the key point is identification of the correct nerve among several candidates; this may be challenging, particularly if there is much scarring from a previous lymph node biopsy.

• Stimulation of the likely candidate will cause backfiring of the SCM. On occasion, a proximal branch of the accessory nerve will be intact, in which case a weak trapezius contraction will be noted. Usually, however, the accessory nerve injury is complete so that no trapezius response is found. Stimulating the proprioceptive nerves will also elicit a negative response. Stimulation of proximal C5 will cause contraction of the levator scapulae, and the inexperienced surgeon may mistake this for trapezius function.

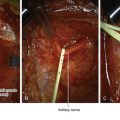

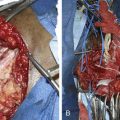

• Every effort should be made to maintain continuity of the eleventh nerve through the scar tissue of the injury site, working from proximal to distal along the shredded nerve and scar, as the next step is to define the distal stump (Figure 6-7). If, however, the nerve is destroyed and is not continuous through the scar tissue, the surgeon will have to seek diligently for short distal branches, a few millimeters in length, that will constitute the points to which grafts will be sewn.

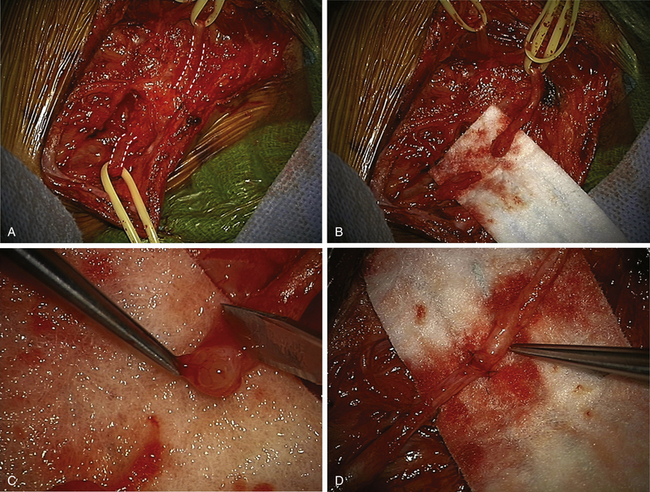

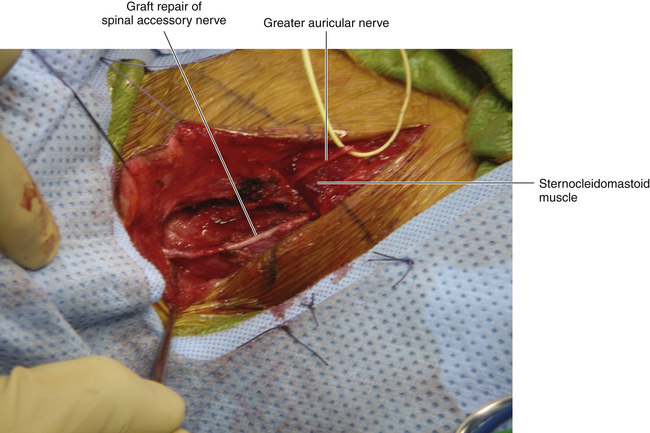

• It is essential that a normal fascicular pattern be seen on both stumps before suturing the grafts (Figure 6-8).

• The graft should be of sufficient length to allow neck movement in the postoperative phase without applying tension to the suture line (Figure 6-9).