CHAPTER 32 Sphenoid Wing Meningiomas

INTRODUCTION

Meningiomas arising in the sphenoid region are frequently encountered in neurosurgical practice. They account for 11% to 18% of cases in large surgical series.1–6 Presumably radiation-induced sphenoid meniningiomas have been described.7,8 Jacobs and co-workers have reported a nonrandom association between sphenoid meningiomas, breast cancer, and genital cancer.9 Other than that, there are no data implicating specific causes or genes and genetic pathways specifically in the formation of sphenoid wing meningiomas.10 Epidemiologists have generally not distinguished between meningiomas occurring at different sites.11,12

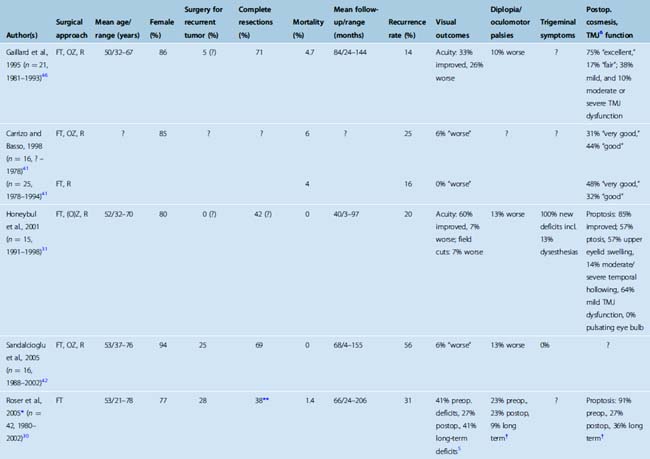

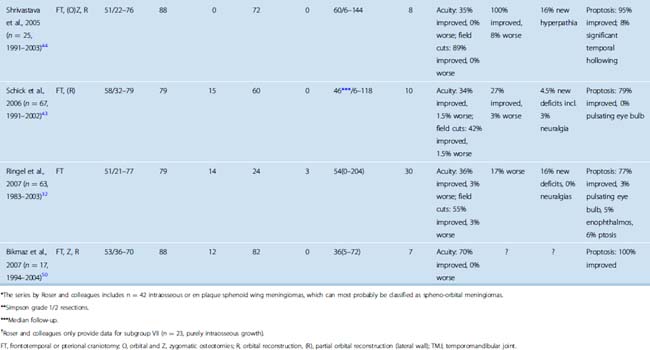

Sphenoid meningiomas (and other meningiomas of the anterior skull base) may be more often of the meningiothelial than the transitional or fibroblastic histologic subtype possibly reflecting a lesser rate of NF2 gene disruptions in these tumors.13 Histologically malignant and atypical tumors of the sphenoid have been reported, but histologically aggressive meningioma variants are less frequently observed in the cranial base than the convexity.14 Overall, meningiomas more commonly affect women. This is particularly true for meningiomas en plaque of the sphenoid wing. Between 77% and 94% of these growths are diagnosed in females (Table 32-1).

TABLE 32-1 Surgery for spheno-orbital meningiomas: summary of published series (1995–2007) including 15 or more patients

This chapter describes the surgical treatment of meningiomas of the sphenoid wing and its results.

CLASSIFICATION OF SPHENOID MENINGIOMAS

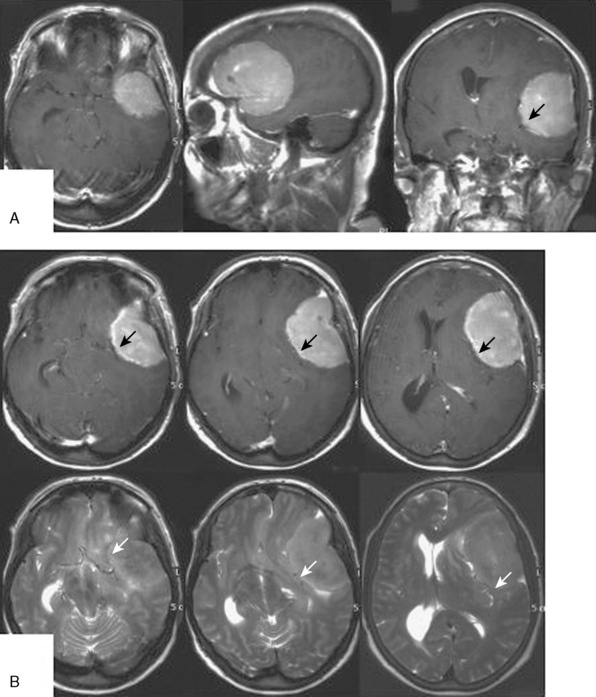

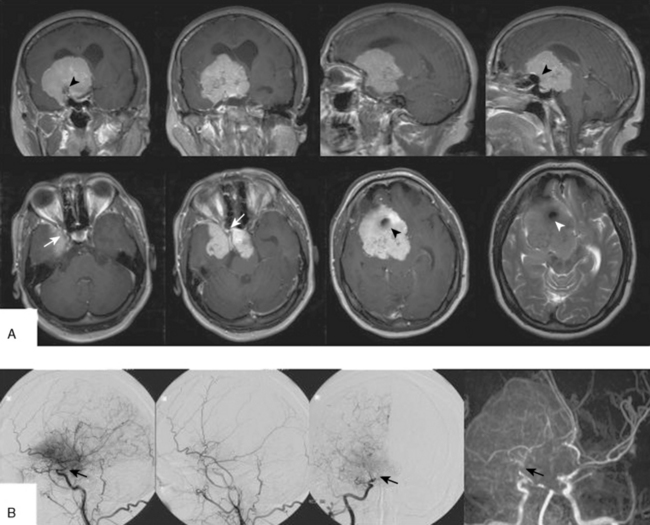

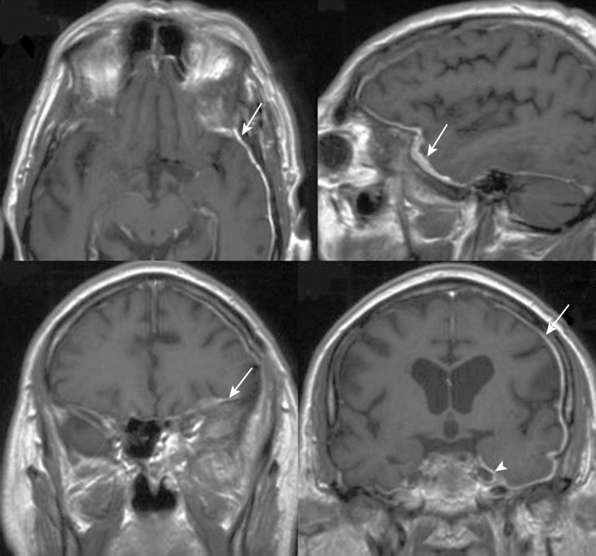

Growth patterns of sphenoid meningiomas reflect the complicated anatomy detailed in the preceding text and may therefore vary considerably. On the end of the spectrum of sphenoid meningiomas are some tumors of the lateral sphenoid wing (or the pterion; see earlier) which closely resemble convexity meningiomas in most aspects of clinical presentation and surgical treatment (Fig. 32-1). On the other hand, many tumors of the medial sphenoid wing are typical skull-base tumors infiltrating into skull-base structures. The proximity of vital and eloquent neurovascular structures such as the carotid artery and its branches and the optic apparatus (Figs. 32-2, 32-3, and 32-4) can pose formidable surgical challenges. Sometimes, tumors not only infiltrate the dural layer but also may grow into the cavernous sinus itself. Orbital involvement and extracranial growth in the subcranial region is a prominent finding in certain sphenoid meningiomas (spheno-orbital meningiomas). Bone invasion and hyperostosis usually associated with en plaque growth along the underlying dura are a characteristic finding in spheno-orbital meningiomas (Figs. 32-5 through 32-8). Excision of the dural origin of the tumor is generally required for a permanent cure of meningiomas.15 This can be regularly achieved when operating on lateral sphenoid wing tumors. In contrast, tumor growth into the cavernous sinus, orbital tumor extensions, and even carpet-like involvement of the convexity dura (see Fig. 32-8) encountered in tumors of the middle and inner thirds of the sphenoid wing may prevent a truly complete and radical resection.

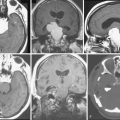

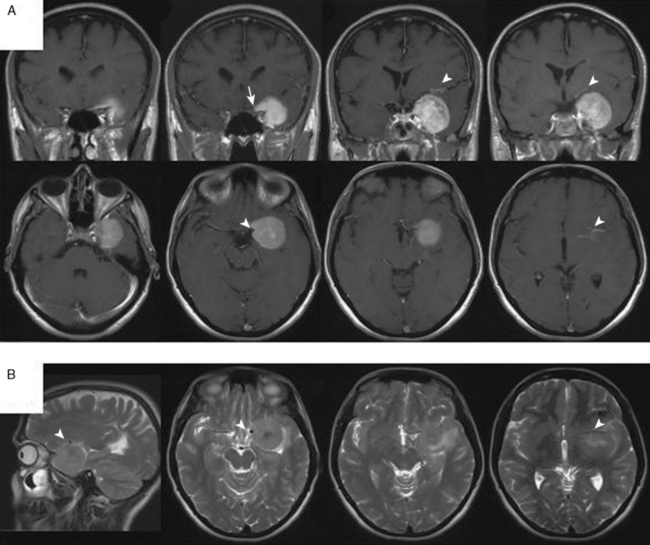

FIGURE 32-3 Medium-sized medial sphenoid wing meningioma.

This tumor was diagnosed in a 39-year-old woman after a seizure. Visual acuity and visual fields were normal. Please compare Figure 32-4 for the corresponding intraoperative findings.

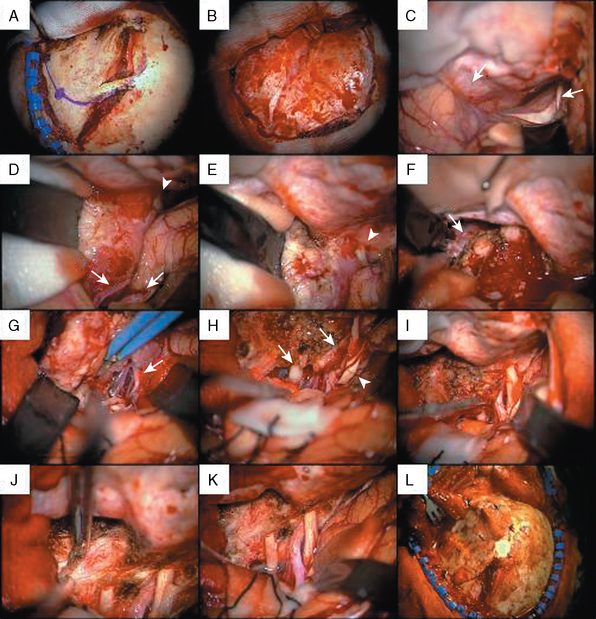

FIGURE 32-4 Surgery for a medium-sized meningioma of the left medial sphenoid wing. Please compare Figure 32-3 for radiologic findings.

I, After decompression of the optic nerve, the dural tumor origin in the region of the anterior clinoid process is removed. There was no tumor growth extending medially or into the optic foramen. Much of the dural sign in this region (compare Fig. 32-3A, upper panel) was found to correspond to neovascularization and not tumor during surgery.

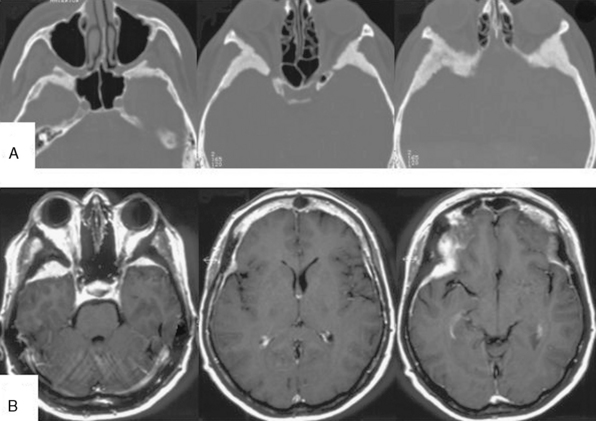

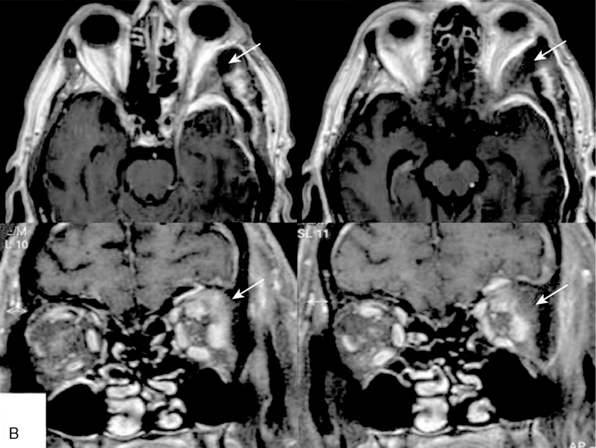

FIGURE 32-5 Bilateral spheno-orbital meningioma.

A, CT scans showing the bony involvement.

B, T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI scans depicting bilateral bone and soft tissue involvement.

(From Ringel F, Cedzich C, Schramm J. Microsurgical technique and results of a series of 63 spheno-orbital meningiomas. Neurosurgery 2007;60(4 Suppl 2):214-21.)

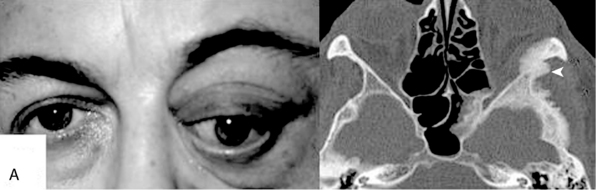

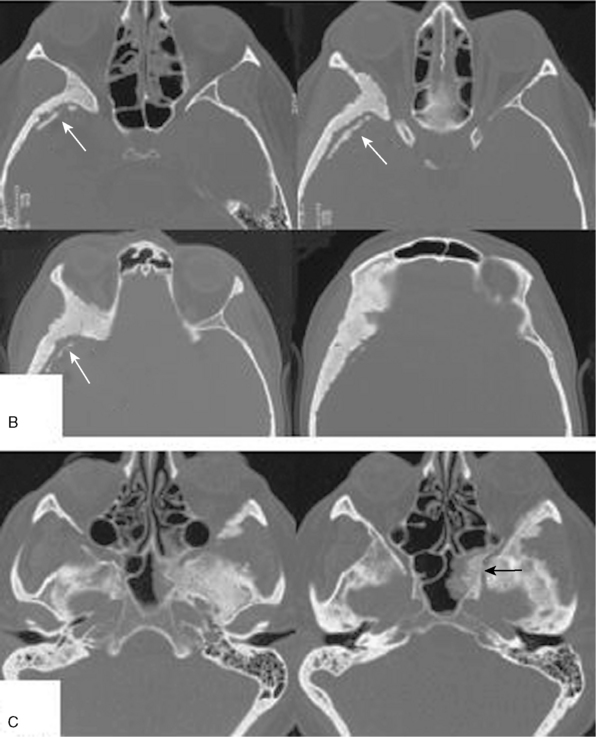

FIGURE 32-6 Orbital involvement in spheno-orbital meningiomas.

(From Ringel F, Cedzich C, Schramm J. Microsurgical technique and results of a series of 63 spheno-orbital meningiomas. Neurosurgery 2007;60(4 Suppl 2):214-21.)

FIGURE 32-7 Intraosseous tumor growth and secondary bone formation in spheno-orbital meningiomas.

(From Ringel F, Cedzich C, Schramm J. Microsurgical technique and results of a series of 63 spheno-orbital meningiomas. Neurosurgery 2007;60(4 Suppl 2):214-21.)

A simple classification of sphenoid meningiomas will distinguish between medial and lateral sphenoid wing meningiomas and spheno-orbital (hyperostosing or en plaque) meningiomas.16–22 The first classification of sphenoid meningiomas was proposed by Cushing.23 Based on different growth patterns, site-dependent symptomatology, and site-specific surgical issues, Cushing and Eisenhardt distinguished between meningiomas of the deep or clinoidal third, those of the middle, and those of the outer (pterional) third of the sphenoid ridge (i.e., the ala magna). Cushing felt that early symptomatic involvement of the optic apparatus, oculomotor palsies, and exophthalmos, and the surgical challenges posed by the vicinity of the carotid artery, the superior orbital fissure, and the pituitary stalk, serve to distinguish tumors of the deep from tumors of the middle sphenoid ridge. The latter may often become sizable growths before they are diagnosed. Pterional meningiomas are thought to either grow en plaque or as sometimes rather large spherical (globular) tumors.

A somewhat more refined classification has been proposed by Bonnal and colleagues and Brotchi and Pirotte.24,25 These authors distinguish between five groups of sphenoidal meningiomas. Cushing’s clinoidal tumors are referred to as group A tumors. Invasion of the cavernous sinus is listed as one characteristic of these growths. Meningiomas en plaque with hyperostosis of the sphenoid bone often invade large parts of the sphenoid bone, the optic foramen and orbit, and even the infratemporal fossa and fossa pterygopalatina (see Figs. 32-6, 32-7, and 32-8). Hence their designation as pterional tumors as proposed by Cushing may not be fully appropriate. These tumors are termed group B meningiomas by Bonnal and colleagues and Brotchi and Pirotte. Large invasive tumors of the sphenoid ridge (“invasion en masse”) are classified as group C tumors. They are thought to combine features of both group A and B tumors: globular and invasive growth en plaque. Group D and E meningiomas correspond to Cushing’s middle sphenoid ridge and globular pterional tumors.

Basso and colleagues subdivide meningiomas of the inner third of the sphenoid wing into clinoidal and sphenocavernous tumors.21 Nakamura and co-workers and Russel and Benjamin also classify medial sphenoid wing meningiomas into tumors with or without cavernous sinus involvement.22,26 Among sphenoid wing meningiomas with growth into the cavernous sinus, Abdel-Aziz and colleagues further distinguish among sphenocavernous, clinoidocavernous, and sphenoclinoidocavernous meningiomas.27 Clinoidal meningiomas may also be subclassified based on the presence (or absence) of interfacing arachnoid membranes between the tumor and cerebral vessels28 and, in addition, tumor size.29

Roser and colleagues described a subset of 86 cases of sphenoid wing meningiomas with osseous involvement among a total of 256 sphenoid wing meningiomas. They distinguish between globular tumors of the lateral, middle, and medial sphenoid wing with osseous infiltration, en plaque meningiomas with and without cavernous sinus invasion, and finally purely intraosseous tumors.30 Honeybul and co-workers also differentiate between invasive en plaque and purely intraosseous sphenoid meningiomas.31

Irrespective of the classification one chooses to subdivide one’s case series, when planning an operation it is important to distinguish among the types outlined by Roser and colleagues,30 that is, the surgical strategy will be influenced by the location of the tumor along the ridge, by the extent of bone infiltration (e.g., with or without involvement of the orbital roof or the base of the middle fossa), and, most importantly, by infiltration of the cavernous sinus. These tumor characteristics and the surgical strategy have to be clear when discussing the surgery with the patient as they relate directly to different types of surgical risks (and complications) and to the chances for complete removal.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Ocular palsies reflect involvement of the cavernous sinus and/or superior orbital fissure by meningiomas of the medial sphenoid wing. Involvement of the cavernous sinus will also often result in sensory loss in the distribution of the ophthalmic (and eventually other) division(s) of the trigeminal nerve. Diplopia due to restriction of ocular movements rather than oculomotor nerve paresis caused by intraorbital tumor growth is a characteristic finding in many spheno-orbital meningiomas. Intraorbital tumor, but also intraosseous growth in the lateral orbital wall and orbital roof, will lead to exophthalmos (see Fig. 32-6). Exophthalmos may also result from venous stasis. Exophthalmos, deterioration of visual acuity and field cuts, and diplopia is the classical presenting triad of spheno-orbital meningiomas. Extracranial tumors growth and hyperostosis may sometimes result in temporal (and frontal) bulging.

Sphenoid meningiomas, especially those of the inner and middle sphenoid wing, may cause uncinate fits and gustatory and olfactory hallucinations. Sometimes psychiatric symptoms may also result. Generalized seizures are seen in patients with large tumors, particularly in cases with tumors of the lateral sphenoid wing. Large tumors of the (lateral) sphenoid wing may also present with hemiparesis and aphasia, if the dominant hemisphere is involved. A general cognitive decline, memory deficits, a flattened affect, and personality changes are also frequently observed in patients with large growths (see Fig. 32-1).

In general, the proximity of the optic apparatus and cavernous sinus will lead to earlier and more specific symptoms in patients with lesions of the medial sphenoid ridge, while tumors of the middle and outer thirds may grow to large size before a seizure or signs related to their mass effect such as hemiparesis and aphasia suggest the diagnosis. The presentation of spheno-orbital meningiomas is also fairly typical.32 Occasionally, the differential diagnosis of unilateral thyroid orbitopathy may cause some confusion, but in most cases the chief problem is the rather insidious clinical course, which often prevents the patients from seeking medical attention early on.

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

The typical presurgical workup will include a triplanar contrast-enhanced T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the depiction of the tumor and its meningeal extensions in relation to the surrounding structures. The MRI will also allow for the diagnosis of a likely meningioma in all but a very few cases. T2-weighted images will usually delineate the course of the major vessels, i.e., the middle cerebral artery in cases of a meningioma of the lateral sphenoid wing (see Fig. 32-1B), or the carotid artery and its major branches in patients with medial sphenoidal wing tumors (see Figs. 32-2 and 32-3). MR or computed tomography (CT) angiography may also help to delineate the course of major cerebral vessels. Some neurosurgeons feel more comfortable assessing the vascular relations of sphenoid meningiomas on digital subtraction angiograms. Medial tumors (see Fig. 32-2) are usually fed by direct (sometimes intracavernous) branches of the internal carotid, or the ascending pharyngeal artery, and sometimes a recurrent branch of the ophthalmic artery passing through the superior orbital fissure. Lateral tumors derive much of their blood supply from the superficial temporal and the middle meningeal arteries. Additional feeding vessels may include the anterior meningeal and other branches of the ethmoidal arteries. Angiography will also allow for a test occlusion of the carotid artery, if sacrifice of this vessel is anticipated. Preoperative embolization with polyvinyl alcohol particles or acrylic microspheres is used as an adjunct in some centers in order to reduce intraoperative blood loss,33–35 although its value has also been questioned.33

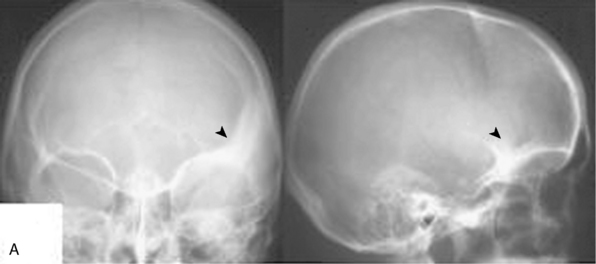

Plain radiographs may show a thickening of the ala minor and the pterion (“smoking pterion”; see Fig. 32-5A). Conventional radiographic studies may allow for the diagnosis of sphenoid meningiomas in up to 90% of cases.21 CT scans (bone window) are necessary to show the extent of bone invasion. For obvious reasons, CT scans are therefore of particular importance for surgical planning in cases with spheno-orbital meningiomas (see Figs. 32-5 and 32-8).

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Lateral Sphenoid Wing Meningiomas

Operations for lateral sphenoid wing tumors aim at the complete removal of the tumor and excision of its dural origin, including a safety margin. This will be possible in most if not all cases. Only in very large tumors encroachment on the superior orbital fissure or cavernous sinus may preclude a surgical cure. Tumors are usually attacked through a generous frontotemporal bone flap, allowing for a complete excision of the dural origin of the tumor and any part of the dura invaded by the meningioma. This is easily accomplished in the frontotemporal region. The pterion should be carefully drilled. This will facilitate early control of the tumor’s main blood supply through dural and pterional branches of the external carotid meningeal artery. Some authors have used preoperative embolization to reduce the tumor’s vascularity.33,35 Drilling the lateral sphenoid wing up to the superior orbital fissure may be necessary to remove all tumor-infiltrated bone.

The dural opening will start laterally in the frontotemporal region. Removal of the tumor will usually start with an internal decompression followed by a careful dissection of the tumor borders. Depending on the consistency of the tumor, using a Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator (CUSA) may be helpful. Major branches of the middle cerebral artery and sometimes the artery itself may be engulfed by the tumor (see Fig. 32-1B), but true invasion of the wall of the middle cerebal artery is very rare.28 Identifying the middle cerebral artery proximal to the tumor nodule may be difficult as an intial step. In many cases it will be relatively easy to separate the middle cerebral artery and its major branches from the capsule of the tumor, and to identify, coagulate, and divide tumor feeding vessels. However, if the tumor has grown around the middle cerebral artery or its branches, the preservation of these vascular structures may become very difficult. Usually it is easiest to identify M2 or M3 branches distal in the sylvian fissure and follow them proximally along the tumor or through it. Some authors have stressed the importance of preserving the superficial sylvian veins.17,25 The bulk of the tumor is removed together with the larger part of its dural origin. Finally, the mediobasal tumor-infiltrated dura is excised.

Medial Sphenoid Wing Meningiomas

Many of the concepts and surgical maneuvers outlined in the preceding text can also be applied to the surgery of medial sphenoid wing meningiomas. Surgery for a typical medium-sized medial sphenoid wing meningioma without growth into the cavernous sinus (see Fig. 32-3) is illustrated in Figure 32-4. The tumor is exposed through a standard pterional craniotomy (see Fig. 32-4A and B) and a transsylvian approach followed by internal decompression (see Fig. 32-4C–F). Some authors have advocated extradural clinoidectomy and unroofing of the optic canal in the case of large tumors and compression of the optic nerve or chiasm in order to prevent additional damage to an already compromised optic apparatus during the intradural dissection.36,37 Others have argued that extensive extradural drilling may even increase the risk for optic nerve damage because of the retraction necessary for these maneuvers.29

Medial sphenoid wing meningiomas will often engulf the internal carotid and middle cerebral artery.22,28 Early visualization of the internal carotid artery is sometimes impossible. Even more often than with lateral wing tumors, one has to identify distal branches of the middle cerebral artery in the sylvian fissure first and follow them medially until one reaches the main trunk of the middle cerebral (and eventually the internal carotid) artery.22 Of note, it is possible to tear the walls of major vessels including the middle cerebral and the internal carotid artery with the CUSA during this stage of the operation.

As noted earlier, meningiomas of the middle sphenoid wing may grow into the cavernous sinus. The outer layer of the wall of the cavernous sinus can be resected (see Fig. 32-4J). Intracavernous tumor is usually left undisturbed in all26,29 but a very few patients with complete ophthalmoplegia.22 Surgery for cavernous sinus meningiomas has been attempted by many groups with modest success at best.38,39 We and many other surgeons currently prefer the option of later radiosurgery for the intracavernous portion of the tumor.

Spheno-orbital Meningiomas

Bicoronal or frontotemporal incisions are used for the surgery of spheno-orbital meningiomas. A bicoronal incision provides access to larger periosteal flaps and bilateral temporalis muscle fascia, and allows for split calvarial grafts. The optimal surgical approach continues to be debated. Several authors have described variations of a combined pterional/frontotemporal and orbitozygomatic approach. In essence, various orbital and zygomatic osteotomies are added to a conventional pterional approach, allowing for a more direct exposure of the lateral orbital wall and the middle fossa. These approaches have been labelled frontotemporal–orbitozygomatic,40 subfrontal–transmalar,21,41 and supraorbital/transzygomatic.31 In some centers, patients with spheno-orbital meningiomas are managed by an interdisciplinary team including neurosurgeons and maxillofacial surgeons.31,42

However, good results with respect to degree of resection and symptom relief have also been obtained utilizing a conventional pterional approach combined with extensive epidural drilling of the sphenoid, the orbital walls, and the base of the middle fossa as evidenced by the data from the two largest series published so far.32,43 Our own practice favors a generous frontotemporal craniotomy large enough to excise the often large zone of dural tumor carpet (en plaque growth) and gives access to the orbital roof and the base of the middle fossa.32,43 Some series in which orbitozygomatic osteotomies were routinely utilized report a significant number of patients with approach-related problems such as temporomandibular joint dysfunction and temporal hollowing.31,44 Zabramski and colleagues observed two cases with severe intraorbital swelling necessitating tarsorrhaphy, and five patients with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistulas in their series of 83 orbitozygomatic craniotomies.45 It is probably fair to state that the surgeon needs to carefully balance the presumed benefits of the use of a skull-base approach against the additional operating time needed and the risks involved.

After completion of the bone resection, the frontotemporal dura is opened beyond the area of tumor infiltration, and all intradural tumor and infiltrated dura is removed up to the superior orbital fissure and the optic canal. Dural resection may include the outer layer of the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. We agree with most authors who do not recommend to enter the cavernous sinus itself (at least not in patients without cranial nerve deficits).30,32,41–44,46 Some authors perform an anterior clinoidectomy and decompression of the optic canal if necessary only after opening the dura and after having obtained visual control of the intracranial portion of the optic nerve.

Significant controversy surrounds the need for orbital reconstruction. There is little doubt that the supraorbital rim margin needs to be preserved (or reconstructed, if violated). There is a considerable body of data suggesting that little more needs to be done in most cases. Maroon and colleagues reported no cases with permanent pulsating enophthalmos after 200 cases of orbital decompression without reconstruction.47 DeMonte and co-workers conclude from their experience with 56 orbital tumors that routine reconstruction after orbital roof resections with or without defects of the medial or lateral orbital wall is not required.48

Others believe that a reconstruction of the orbit is warranted if more than one of its walls has been removed.21,31,41,42,44,46,49,50 The lateral orbital wall and the orbital roof can be reconstructed using autologous bone (i.e., calvarial split grafts or iliac crest bone)42,43 or a variety of alloplastic materials,44 or titanium mesh.51 Titanium plate fixation is usually necessary after orbito-zygomatic osteostomies. Advocates of a routine reconstruction of bone defects after surgery for spheno-orbital meningiomas argue that reconstruction will prevent complications such as enopthalmos, pulsating eye bulbs, and oculomotor muscle fibrosis.41,44,52,53 However, Ringel and co-workers reported only a 5% enophthalmos rate, and a 3% rate of pulsating eye bulbs after minimal orbital reconstruction with fibrin glue and Gelfoam.32 Reconstructive procedures may interfere with postoperative surveillance imaging.

SURGICAL RESULTS

Recurrence rates after surgery for sphenoid ridge meningiomas are considerable. Between 15.6% and 54% of tumors may recur after 10 years.2–5,15,30 Regrettably, most authors fail to distinguish between the various categories of sphenoid meningiomas with their vastly different growth patterns and degrees of resectability. Basso and co-workers detail a 24% recurrence rate after 9 to 30 years for medial sphenoid wing tumors versus 18% for meningiomas of the middle and lateral third of the sphenoid ridge.21 Philippon reports less than 10% recurrences for lateral sphenoid wing versus 25% for medial sphenoid wing meningiomas at 10 years.3 Roser and co-workers observed 11.6% recurrences after surgery for sphenoid wing meningiomas without osseous involvement, but a 30.6% recurrence rate for tumors with bone infiltration after a mean follow-up of 66 months.30

Most globular tumors of the middle and outer thirds of the sphenoid wing with little or no bone infiltration can be resected completely with a dural safety margin as noted earlier. The degree of resection may be described as Simpson grade 115 or even grade “zero.”54 Such resections will conceptually result in surgical cures. However, realistically one should expect recurrence rates similar to the numbers published for convexity meningiomas, that is, in the range of 5% to 10%.3 Complication rates will probably also resemble those seen for convexity tumors. Obviously, morbidity and mortality will vary with certain tumor characteristics. Increasing tumor size correlates with peritumoral edema, pial vascularization of the tumor, and ultimately a failure to maintain an extrapial dissection plane resulting in cortical damage and neurologic deficits.55–57 No surgical morbidity and mortality was observed in a series of 37 convexity meningiomas reported by Kinjo and colleagues.54 A 2.3% in-house mortality rate and 4.5% neurologic complications after meningioma surgery have been reported in a very large (n = 15,028) community-based American cohort based on a hospital discharge database without site specification.58

Involvement of the optic apparatus and anterior circulation arteries sometimes renders medial sphenoid wing meningiomas formidable lesions. Pamir and colleagues have pointed to the importance of tumor size with respect to surgical risks.29 Complete resections (i.e., Simpson grades 1 and 2) for clinoidal meningiomas have been achieved in 87% to 96% of cases in the more recent series.22,26,29,36 As noted earlier, there is general agreement that operations for sphenocavernous meningiomas do not aim at a complete tumor removal. Accordingly, recurrence rates of 0% to 9% for clinoidal and 11% to 27.5% for sphenocavernous tumors have been reported.22,26,27,29 Patients with visual impairments will often (i.e., 56%–85%) improve.22,26,29,36 However, visual deterioration may occur in 0 to 6%.22,26,29,36 A new hemiparesis after surgery or a new aphasia may occur in up to 10% and 5% of patients, respectively.22,26,29,36 Of note, these data come from specialized centers, and higher complication rates can be expected in less experienced hands.

The treatment of spheno-orbital meningiomas poses different challenges. Spheno-orbital meningiomas commonly lack a large globular intradural component. Hence, a spheno-orbital meningioma is in most cases probably not a life-threatening disease, but if the tumor is left untreated, progressive loss of vision due to optic atrophy and exophthalmos, and significant facial deformity will occur. Historically, exophthalmos has occasionally required enucleation of the affected eye. Restricted eye movements and ocular palsies may render a seeing eye functionally useless. Several series of spheno-orbital meningiomas have been published in recent years,30–32,41–44,46,50 providing detailed accounts of the surgical techniques utilized and surgical outcomes. Results have markedly improved in the last two decades when compared to earlier series (for review, see, e.g., ref. 46). Table 32-1 summarizes the results of surgical series published after 1995 including 15 or more patients. There is a fair chance (>30%) that visual dysfunction will improve after surgery. Deterioration is rare. Cosmetic results are acceptable in many but not all cases.

Published recurrence rates after surgery for spheno-orbital meningiomas remain substantial as outlined earlier. In all likelihood, this is a testament to the difficulty of achieving a truly complete resection. Widespread infiltration of the bony skull base and dura, but also involvement of the cavernous sinus, the orbital sheath, and the annulus of Zinn, may preclude a radical resection. Surgery even for benign cavernous sinus meningiomas with its attendant morbidity does not guarantee a cure.38,39

The percentage of cases with a (presumably) complete resection, that is, complete removal of the tumor’s soft tissue component, and all tumor-infiltrated dura and bone, varies considerably between series (see Table 32-1). This may reflect different treatment philosophies. As noted earlier, one can argue that surgery for spheno-orbital meningiomas aims at symptom control and improvement rather than cure. Assessing the degree of resection is not a trivial matter. Postoperative CT scans are necessary to delineate residual tumor-infiltrated bone. MRI scans will not reliably show dural invasion, that is, even CT and MRI scans together will not distinguish among Simpson resection grades 1, 2, and 3. Of note, follow-up for many published patients does not exceed 5 years, while many benign meningiomas will recur later. Stafford and co-workers report a 88% recurrence-free survival rate 5 years after surgery in a large series comprising 582 meningiomas. This number drops to 75% at 10 years.6

Residual disease may often be simply followed. In the series by Ringel and co-workers 61% of patients with known residual disease remained stable and did not require further intervention during of mean follow-up of 54 months.32 This has led some to propose very limited surgical interventions in selected cases. Lund and Rose59 have performed transnasal endoscopic decompressions of the orbital apex in 12 patients with spheno-orbital meningiomas. Improvement of visual function was seen in seven patients (58%), and proptosis improved in four (25%).

Radiotherapy can prevent tumor recurrence and control progressive disease. Peele and colleagues have reported a series of 86 subtotally resected or recurrent sphenoid wing meningiomas.60 Conventional fractionated radiotherapy was administered in 42 cases. No recurrences were seen during follow-up, while a 48% recurrence rate was observed in the control group. Acute onset ischemic neuropathy 6 months after radiotherapy was seen in one case. Mean follow-up ranged between 3.5 and 4.4 years in the various patient subgroups (radiotherapy or no radiotherapy for recurrent or primary, subtotally resected tumors). Nutting and colleagues report a 69% 10-year progression-free survival rate after surgery and fractionated radiotherapy for sphenoid wing meningiomas.61 Cavernous sinus disease is often well controlled by radiosurgery or stereotactic radiotherapy.62–64 Limited data indicate that radiotherapy may also control residual intraorbital tumor.43

We caution that the current enthusiasm with respect to modern radiotherapeutic options should not deter the neurosurgeon from aggressive surgery when appropriate. Conservative surgery and radiotherapy for a challenging lesion may result in a patient 10 years older with a progressive and unresectable tumor, and little therapeutic options. Follow-up data more than 20 years after meningioma radiosurgery are rare, and the risk of the formation of radiation-induced cancers may be an underappreciated concern, especially in younger patients.65

[1] Rohringer M., Sutherland G.R., Louw D.F., Sima A.A. Incidence and clinicopathological features of meningioma. J Neurosurg. 1989;71(5 Pt 1):665-672.

[2] Jaaskelainen J. Seemingly complete removal of histologically benign intracranial meningioma: late recurrence rate and factors predicting recurrence in 657 patients. A multivariate analysis. Surg Neurol. 1986;26(5):461-469.

[3] Philippon J., Cornu P. The recurrence of meninigiomas. In: Al-Mefty O., editor. Meningiomas. New York: Raven Press; 1991:87-106.

[4] Baird M., Gallagher P.J. Recurrent intracranial and spinal meningiomas: clinical and histological features. Clin Neuropathol. 1989;8(1):41-44.

[5] Mirimanoff R.O., Dosoretz D.E., Linggood R.M., et al. Meningioma: analysis of recurrence and progression following neurosurgical resection. J Neurosurg. 1985;62(1):18-24.

[6] Stafford S.L., Perry A., Suman V.J., et al. Primarily resected meningiomas: outcome and prognostic factors in 581 Mayo Clinic patients, 1978 through 1988. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73(10):936-942.

[7] Al-Mefty O., Topsakal C., Pravdenkova S., et al. Radiation-induced meningiomas: clinical, pathological, cytokinetic, and cytogenetic characteristics. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(6):1002-1013.

[8] Kadasheva A.B., Cherekaev V.A., Kozlov A.V., et al. [Meningiomas of the wings of the basilar bone in patients undergone a course of radiation therapy for retinoblastoma in infancy (analysis of 3 cases)]. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko. 2004;3:24-27. discussion 27

[9] Jacobs D.H., McFarlane M.J., Holmes F.F. Female patients with meningioma of the sphenoid ridge and additional primary neoplasms of the breast and genital tract. Cancer. 1987;60(12):3080-3082.

[10] Simon M., Bostrom J.P., Hartmann C. Molecular genetics of meningiomas: from basic research to potential clinical applications. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(5):787-798. discussion 798

[11] Barnholtz-Sloan J.S., Kruchko C. Meningiomas: causes and risk factors. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23(4):E2.

[12] Claus E.B., Bondy M.L., Schildkraut J.M., et al. Epidemiology of intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(6):1088-1095. discussion 1095

[13] Kros J., de Greve K., van Tilborg A., et al. NF2 status of meningiomas is associated with tumour localization and histology. J Pathol. 2001;194(3):367-372.

[14] Sade B., Chahlavi A., Krishnaney A., et al. World Health Organization Grades II and III meningiomas are rare in the cranial base and spine. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(6):1194-1198. discussion 1198

[15] Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20(1):22-39.

[16] Kempe L.C. Sphenoid ridge meningiomas. In: Operative Neurosurgery. Heidelberg: Springer; 1968:109-118.

[17] Fohanno D., Bitar A. Sphenoidal ridge meningioma. Adv Tech Stand Neurosurg. 1986;14:137-174.

[18] Ojemann R. Meningiomas. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1990;1(1):181-197.

[19] Black P.M. Meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1993;32(4):643-657.

[20] Whittle I.R., Smith C., Navoo P., Collie D. Meningiomas. Lancet. 2004;363(9420):1535-1543.

[21] Basso A., Carrizo A.G., Antico J. Sphenoid ridge meningiomas. In: Schmidek H.H., Roberts D.W., editors. Schmidek and Sweet Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. 5th ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 2005:226-237.

[22] Russel S.M., Benjamin V. Medial sphenoid ridge meningiomas: classification, microsurgical anatomy, operative nuances, and long-term surgical outcome in 35 consecutive cases. Neurosurgery. 2008;62(3 Suppl. 1):38-50. discussion

[23] Cushing H., Eisenhardt L. Meningiomas of the sphenoid wing. In: Meningiomas: Their Classification, Regional Behaviour, Life History, and Surgical End Results. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1938:298-387.

[24] Bonnal J., Thibaut A., Brotchi J., Born J. Invading meningiomas of the sphenoid ridge. J Neurosurg. 1980;53(5):587-599.

[25] Brotchi J., Pirotte B. Sphenoid wing meningiomas. In: Sekhar L.N., Fessler R.G., editors. Atlas of Neurosurgical Techniques: Brain. New York, Stuttgart: Thieme; 2006:623-632.

[26] Nakamura M., Roser F., Jacobs C., et al. Medial sphenoid wing meningiomas: clinical outcome and recurrence rate. Neurosurgery. 2006;58(4):626-639. discussion 639

[27] Abdel-Aziz K.M., Froelich S.C., Dagnew E., et al. Large sphenoid wing meningiomas involving the cavernous sinus: conservative surgical strategies for better functional outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2004;54(6):1375-1383. discussion 1383–4

[28] Al-Mefty O. Clinoidal meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1990;73(6):840-849.

[29] Pamir M.N., Belirgen M., Ozduman K., et al. Anterior clinoidal meningiomas: analysis of 43 consecutive surgically treated cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150(7):625-635. discussion 635–6

[30] Roser F., Nakamura M., Jacobs C., et al. Sphenoid wing meningiomas with osseous involvement. Surg Neurol. 2005;64(1):37-43. discussion

[31] Honeybul S., Neil-Dwyer G., Lang D.A., et al. Sphenoid wing meningioma en plaque: a clinical review. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2001;143(8):749-757. discussion 758

[32] Ringel F., Cedzich C., Schramm J. Microsurgical technique and results of a series of 63 spheno-orbital meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(4 Suppl 2):214-221. discussion 221–2

[33] Bendszus M., Rao G., Burger R., et al. Is there a benefit of preoperative meningioma embolization? Neurosurgery. 2000;47(6):1306-1311. discussion 1311–2

[34] Rosen C.L., Ammerman J.M., Sekhar L.N., Bank W.O. Outcome analysis of preoperative embolization in cranial base surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2002;144(11):1157-1164.

[35] Dowd C.F., Halbach V.V., Higashida R.T. Meningiomas: the role of preoperative angiography and embolization. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15(1):E10.

[36] Lee J.H., Jeun S.S., Evans J., Kosmorsky G. Surgical management of clinoidal meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2001;48(5):1012-1019. discussion 1019–21

[37] Lee J.H., Sade B., Park B.J. A surgical technique for the removal of clinoidal meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 59(1 Suppl. 1), 2006. ONS108–14; discussion ONS-114

[38] Sindou M., Wydh E., Jouanneau E., et al. Long-term follow-up of meningiomas of the cavernous sinus after surgical treatment alone. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(5):937-944.

[39] DeMonte F., Smith H.K., al-Mefty O. Outcome of aggressive removal of cavernous sinus meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1994;81(2):245-251.

[40] McDermott M.W., Durity F.A., Rootman J., Woodhurst W.B. Combined frontotemporal-orbitozygomatic approach for tumors of the sphenoid wing and orbit. Neurosurgery. 1990;26(1):107-116.

[41] Carrizo A., Basso A. Current surgical treatment for sphenoorbital meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 1998;50(6):574-578.

[42] Sandalcioglu I.E., Gasser T., Mohr C., et al. Spheno-orbital meningiomas: interdisciplinary surgical approach, resectability and long-term results. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2005;33(4):260-266.

[43] Schick U., Bleyen J., Bani A., Hassler W. Management of meningiomas en plaque of the sphenoid wing. J Neurosurg. 2006;104(2):208-214.

[44] Shrivastava R.K., Sen C., Costantino P.D., Della Rocca R. Sphenoorbital meningiomas: surgical limitations and lessons learned in their long-term management. J Neurosurg. 2005;103(3):491-497.

[45] Zabramski J.M., Kiris T., Sankhla S.K., et al. Orbitozygomatic craniotomy. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1998;89(2):336-341.

[46] Gaillard S., Lejeune J.P., Pellerin P., et al. [Long-term results of the surgical treatment of spheno-orbital osteomeningioma]. Neurochirurgie. 1995;41(6):391-397.

[47] Maroon J.C., Kennerdell J.S., Vidovich D.V., et al. Recurrent spheno-orbital meningioma. J Neurosurg. 1994;80(2):202-208.

[48] DeMonte F., Tabrizi P., Culpepper S.A., et al. Ophthalmological outcome after orbital entry during anterior and anterolateral skull base surgery. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(4):851-856.

[49] Gaillard S., Pellerin P., Dhellemmes P., et al. Strategy of craniofacial reconstruction after resection of spheno-orbital “en plaque” meningiomas. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(5):1113-1120.

[50] Bikmaz K., Mrak R., Al-Mefty O. Management of bone-invasive, hyperostotic sphenoid wing meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(5):905-912.

[51] Kuttenberger J.J., Hardt N. Long-term results following reconstruction of craniofacial defects with titanium micro-mesh systems. J Maxillofac Surg. 2001;29(2):75-81.

[52] Kelly C.P., Cohen A.J., Yavuzer R., Jackson I.T. Cranial bone grafting for orbital reconstruction: is it still the best? J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16(1):181-185.

[53] Leake D., Gunnlaugsson C., Urban J., Marentette L. Reconstruction after resection of sphenoid wing meningiomas. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2005;7(2):99-103.

[54] Kinjo T., al-Mefty O., Kanaan I. Grade zero removal of supratentorial convexity meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1993;33(3):394-399. discussion 399

[55] Sindou M.P., Alaywan M. Most intracranial meningiomas are not cleavable tumors: anatomic-surgical evidence and angiographic predictibility. Neurosurgery. 1998;42(3):476-480.

[56] Kozler P., Benes V., Netuka D., et al. Preoperative neuroimage findings as a predictor of postoperative neurological deficit in intracranial meningiomas. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2007;68(4):190-194.

[57] Tamiya T., Ono Y., Matsumoto K., Ohmoto T. Peritumoral brain edema in intracranial meningiomas: effects of radiological and histological factors. Neurosurgery. 2001;49(5):1046-1051. discussion 1051–2

[58] Curry W.T., McDermott M.W., Carter B.S., Barker F.G.2nd. Craniotomy for meningioma in the United States between 1988 and 2000: decreasing rate of mortality and the effect of provider caseload. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(6):977-986.

[59] Lund V.J., Rose G.E. Endoscopic transnasal orbital decompression for visual failure due to sphenoid wing meningioma. Eye. 2006;20(10):1213-1219.

[60] Peele K.A., Kennerdell J.S., Maroon J.C., et al. The role of postoperative irradiation in the management of sphenoid wing meningiomas. A preliminary report. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(11):1761-1766. discussion 1766–7

[61] Nutting C., Brada M., Brazil L., et al. Radiotherapy in the treatment of benign meningioma of the skull base. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(5):823-827.

[62] Lee J.Y., Niranjan A., McInerney J., et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery providing long-term tumor control of cavernous sinus meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(1):65-72.

[63] Selch M.T., Ahn E., Laskari A., et al. Stereotactic radiotherapy for treatment of cavernous sinus meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(1):101-111.

[64] Hasegawa T., Kida Y., Yoshimoto M., et al. Long-term outcomes of Gamma knife surgery for cavernous sinus meningioma. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(4):745-751.

[65] Balasubramaniam A., Shannon P., Hodaie M., et al. Glioblastoma multiforme after stereotactic radiotherapy for acoustic neuroma: case report and review of the literature. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9(4):447-453.