21 SPERM TRANSPORT AND MATURATION

DEVELOPMENT OF THE GONADS

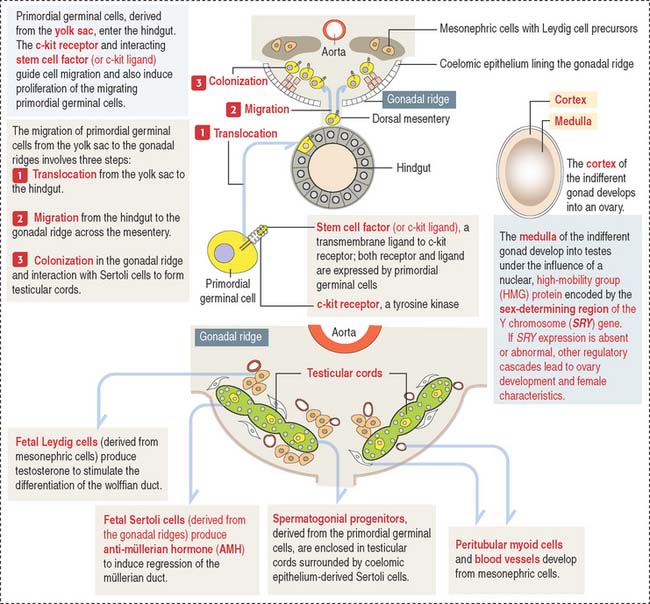

An important aspect to keep in mind is that the cell precursors of both gametes have an extra-embryonic origin. Primordial germinal cells (PGCs) appear first in the endoderm of the yolk sac wall in the 4-week fetus (Figure 21-1).

The migration and proliferation of primordial germinal cells are dependent on the interaction of the c-kit receptor, a tyrosine kinase, with its corresponding cell membrane ligand, stem cell factor (or c-kit ligand). Both the c-kit receptor and stem cell factor are produced by primordial germinal cells along their migration route.

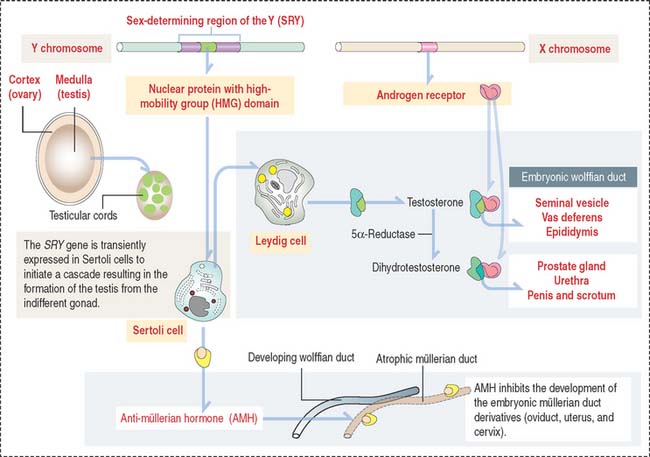

Role of the anti-müllerian hormone and testosterone in the development of male and female internal genitalia

Fetal Sertoli cells secrete anti-müllerian hormone (AMH), which prevents müllerian ducts (also called paramesonephric ducts) from developing into the uterovaginal primordium (Figure 21-2). In the absence of AMH, the müllerian ducts persist and become the female internal genitalia.

In the absence of androgen, the wolffian duct regresses and the prostate fails to develop. If high levels of androgen are present in the female fetus, both müllerian and wolffian ducts can persist (see Box 21-A).

Box 21-A Development of internal genitalia

Testicular descent

The gubernaculum forms on the lower pole of the testis, crosses obliquely through the abdominal wall, and attaches the testis to the scrotal swelling. By week 28, the testis moves deep into the inguinal ring. The gubernaculum grows and the testis descends into the scrotum. For additional details, see Cryptorchidism (or undescended testis) in Chapter 20, Spermatogenesis.

Clinical significance: Klinefelter’s syndrome

The excess of estradiol can lead to phenotypic feminization, including gynecomastia.

Clinical significance: Androgen insensitivity syndrome (testicular feminization)

At puberty, the production of both androgen and estradiol increases (the latter from peripheral aromatization of androgens). Androgens cannot inhibit LH secretion (because a defective androgen receptor prevents LH feedback inhibition), and plasma levels of androgens remain high.

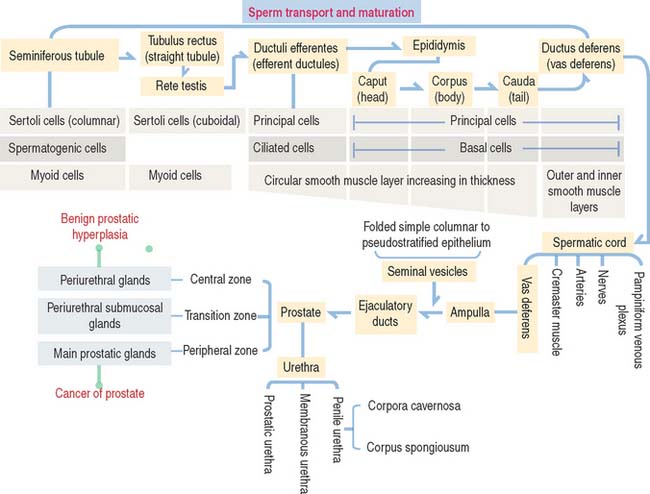

SPERM MATURATION PATHWAY

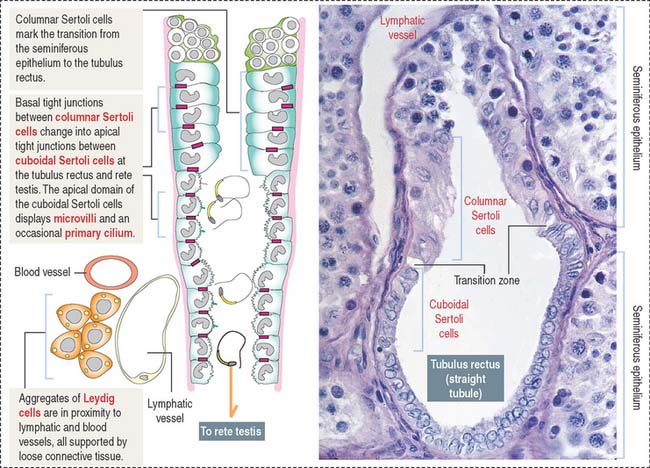

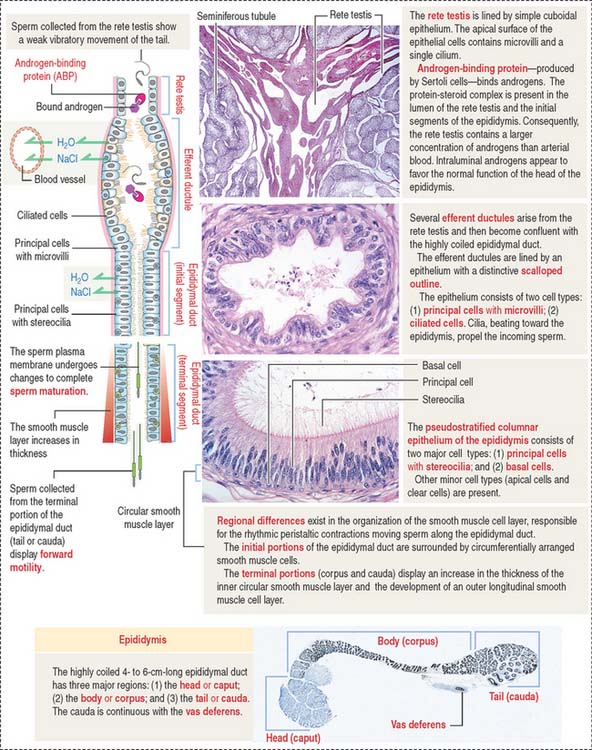

After transport to the rete testis through a connecting tubulus rectus (Figure 21-3), sperm enter the ductuli efferentes. Ductuli efferentes link the rete testis to the initial segment of the epididymal duct, an irregularly coiled duct extending to the ductus, or vas deferens.

The rete testis consists of irregularly anastomosing channels within the mediastinum of the testis (Figure 21-4). These channels are lined by a simple cuboidal epithelium. The wall, formed by fibroblasts and myoid cells, is surrounded by large lymphatic channels and blood vessels associated with large clusters of Leydig cells.

About 12 to 20 ductuli efferentes (efferent ductules) link the rete testis to the epididymis after piercing the testicular tunica albuginea. Each ductule is lined by a columnar epithelium with principal cells with microvilli—with a role in the reabsorption of fluid from the lumen—and ciliated cells, which contribute to the transport of nonmotile sperm toward the epididymis. The epithelium has a characteristic scalloped outline that enables identification of the ductuli efferentes (see Figure 21-4). A thin inner circular layer of smooth muscle cells underlies the epithelium and its basal lamina.

The epididymal duct is subdivided into three major segments: (1) the head or caput; (2) the body or corpus; and (3) the tail or cauda (see Figure 21-4).

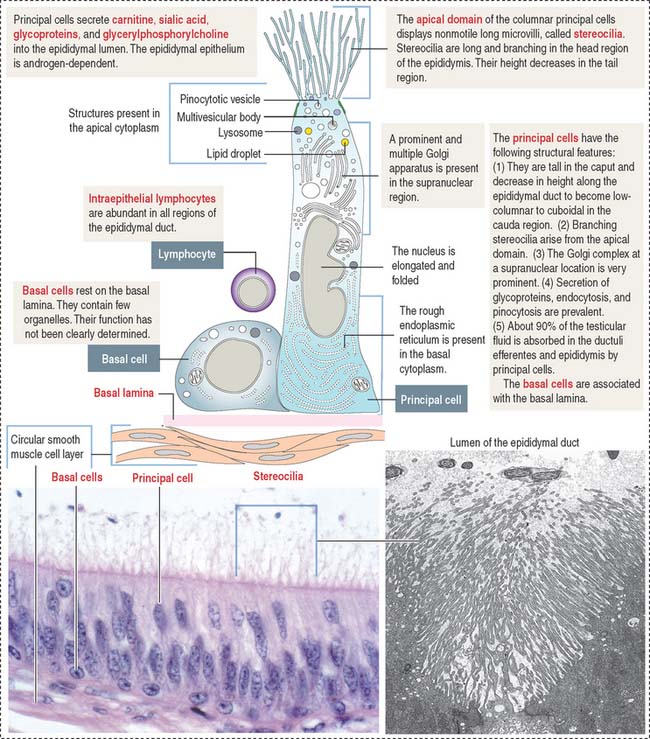

The epithelium is pseudostratified columnar with long and branched stereocilia. The epithelium consists of two major cell types (Figure 21-5):

An inner smooth muscle circular layer, of increasing thickness from head to tail, and an outer longitudinal layer, visible from the body on, surround the epithelium and basal lamina. The muscle layer displays peristaltic movements to facilitate sperm transport along the epididymal duct (Box 21-B).

Box 21-B Epididymal duct

The epididymis has three main functions:

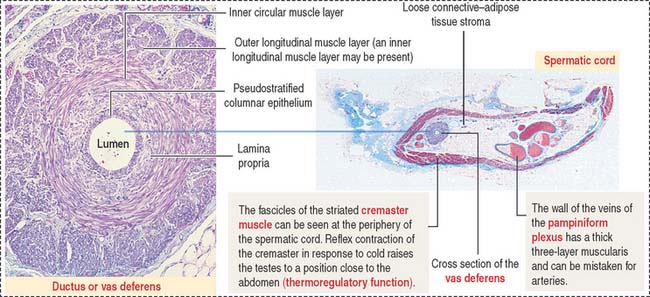

In addition to the vas deferens, the spermatic cord contains the following components (Figure 21-6): (1) the cremaster muscle, (2) arteries (spermatic artery, cremasteric artery, and artery to the vas deferens), (3) veins of the pampiniform plexus, and (4) nerves (genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, cremasteric nerve, and sympathetic branches of the testicular plexus). All these structures are surrounded by loose connective tissue.

SEMINAL VESICLES

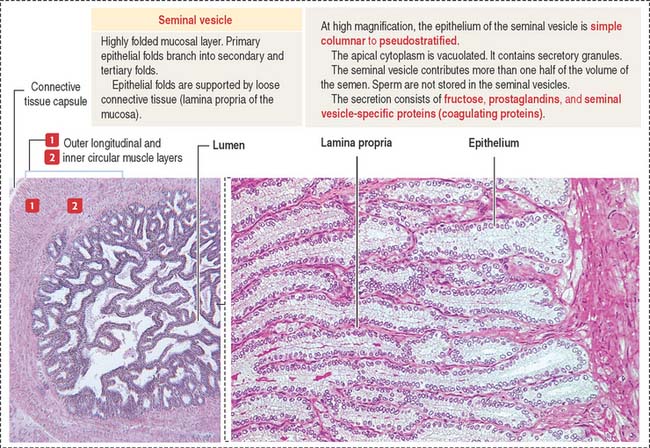

The seminal vesicles are androgen-dependent organs. Each seminal vesicle is an outpocketing of the wall of ampulla of each vas deferens. It consists of three components (Figure 21-7): (1) an external connective tissue capsule; (2) a middle smooth muscle layer (inner circular and outer longitudinal layers), and (3) an internal highly folded mucosa lined by a simple cuboidal-to-pseudostratified columnar epithelium.

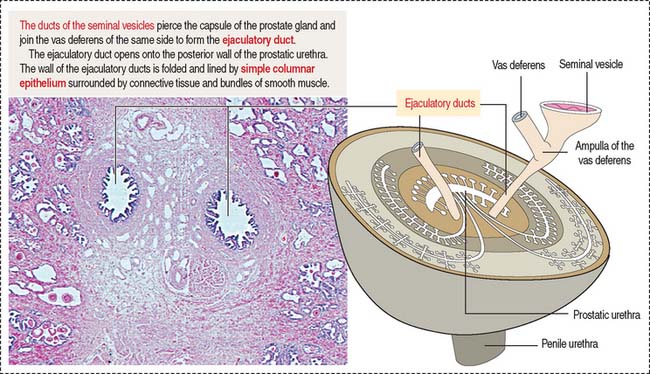

Fructose is the major source of energy of the ejaculated sperm. Seminal vesicles do not store sperm. They contract during ejaculation. The excretory duct of each seminal vesicle penetrates the prostate after joining the vas deferens to form the ejaculatory duct (Figure 21-8).

PROSTATE GLAND

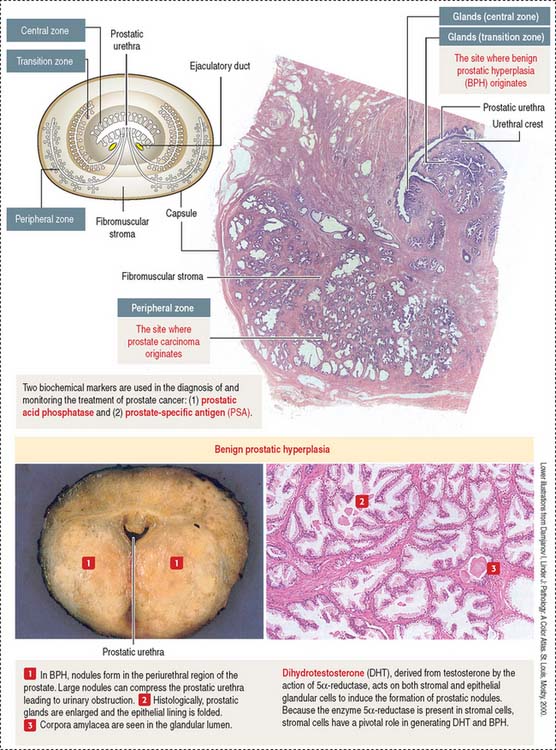

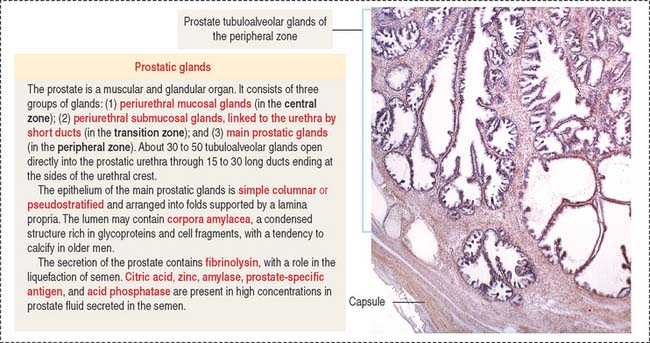

The prostate glands are arranged in three zones (Figure 21-9): (1) a central zone with periurethral mucosal glands, (2) a transition zone with periurethral submucosal glands, and (3) a peripheral zone consisting of branched (compound) glands. About 70% to 80% of prostate cancer originates in the peripheral zone.

The prostate glands are lined by simple or pseudostratified columnar epithelium (Figure 21-10). The lumen contains concretions (corpora amylacea) rich in glycoproteins and, sometimes, a site of calcium deposition. Cells contain abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus.

Clinical significance: Benign prostate hyperplasia and prostate cancer

The periurethral mucosal (central zone) and submucosal (transition zone) prostate glands and the stroma undergo nodular hyperplasia (see Figure 21-9) in older men.

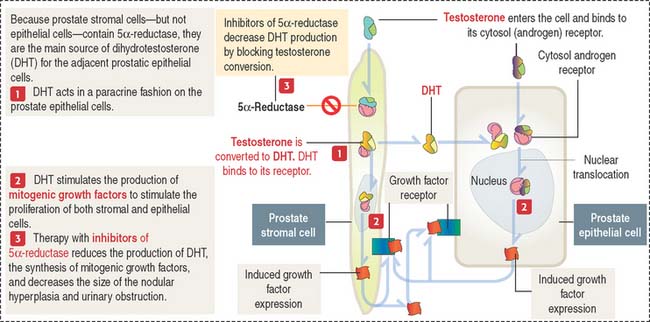

BPH is caused by DHT, a metabolite of testosterone (Figure 21-11). The enzyme 5α-reductase, present mainly in prostate stromal cells, converts testosterone to DHT.

DHT binds to cytosol and nuclear androgen receptors to induce the expression of growth factors mitogenic to prostate epithelial and stromal cells. Inhibitors of 5α-reductase reduce the production of DHT, decrease the periurethral nodular hyperplasia, and alleviate urinary obstruction.

As in BPH, androgens also play a role in the development of prostate carcinoma. Tumor growth can be controlled by reducing androgen production (for example, using luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone [LH-RH] agonists and antiandrogens) or, in hormone-resistant prostate cancer, by orchidectomy (surgical removal of the testes, the major source of androgens) and chemotherapy.

MALE AND FEMALE URETHRA

The urethra in the male is 20 cm long and has three segments:

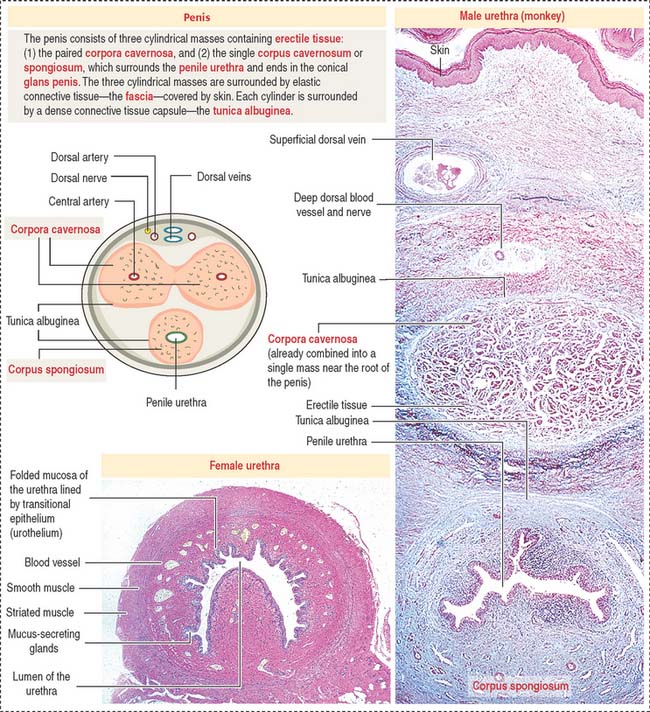

The urethra in the female is 4 cm long and is lined by transitional epithelium changing to pseudostratified columnar and stratified squamous nonkeratinized epithelium near the urethral meatus. The mucosa contains mucus-secreting glands (see Figure 21-12). An inner layer of smooth muscle is surrounded by a circular layer of striated muscle that closes the urethra when contracted.

PENIS

The penis consists of three cylindrical columnar masses of erectile tissue (see Figure 21-12): the right and left corpora cavernosa, and the ventral corpus spongiosum, transversed by the penile urethra. The three columns converge to form the shaft of the penis. The distal tip of the corpus spongiosum is the glans penis.

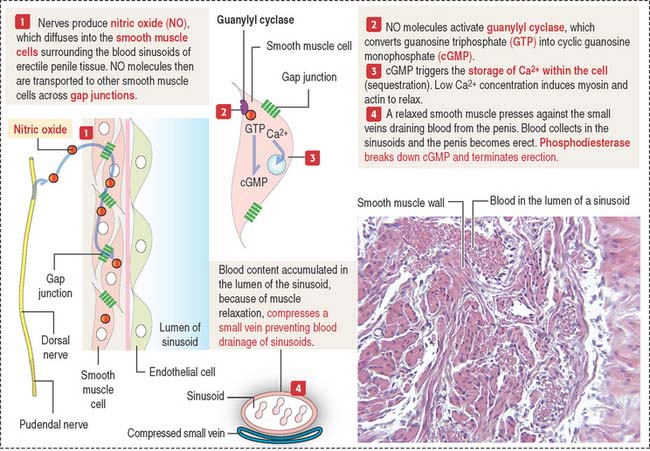

The corpora cavernosa and corpus spongiosum contain irregular and communicating blood spaces, or sinusoids, supplied by an artery and drained by venous channels. During erection, arterial blood fills the sinusoids, which enlarge and compress the draining venous channels (Figure 21-13).

Two chemicals control erection: nitric oxide and phosphodiesterase (see Figure 21-13).

cGMP relaxes the smooth muscle cell wall surrounding the sinusoids by inducing the sequestration of Ca2+ within intracellular storage sites. The lowered concentrations of Ca2+ determine the relaxation of smooth muscle cells, which leads to the accumulation of blood in the sinusoids by the rapid flow of arterial blood from the dorsal and cavernous arteries (see Figure 21-13). Sinusoids engorged with blood compress the small veins that drain blood from the penis and the penis becomes erect.

Clinical significance: Erectile dysfunction

Sperm Transport and Maturation

Essential concepts

Bulbourethral glands secrete a lubricating mucus product into the penile urethra.