Chapter 56 Speech-ready, long-termtube-free tracheostomy for obstructive sleep apnea

1 INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is caused by obstacles to the free flow of air through the upper airway from the lips or nasal tip to the larynx and therefore is within the otolaryngologist’s sphere of responsibility. Management can involve weight loss, treatment of nasal obstruction, surgery of the pharynx, or the use of various ventilatory assist devices such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). This condition has serious health risks and consequences and should be thoroughly researched and investigated to be treated effectively. Furthermore, it is often multifactorial, requiring a multidisciplinary approach to identify the etiology and optimal treatment for each patient.

1.1 SEMANTIC CLARIFICATION

Historically, the documented performance of tracheo-tomy (semantically misrepresented as tracheostomy) for ‘Pickwickian syndrome’ was first described in 1969.1 Since then various modifications of the procedure have evolved into the ‘gold standard’ for management of OSA because, when successful, it bypasses upper airway obstruction in 100% of the cases in which it is used.2 Unfortunately, as mentioned above, patients with OSA are often difficultcandidates for performance and maintenance of routine tube-dependent tracheotomy; their unfavorable anatomy may be compounded by obesity, diabetes, infection and cardiopulmonary comorbidity. With each negative experience, lessons were learned that led to modifications of tracheotomy as it related to the treatment of OSA. Through this process, tracheotomy evolved into increasingly refined techniques such as tube-dependent tracheostomy and subsequently into the tube-free tracheostomy which has been researched, promoted and formulated by the authors. Further classification of these terms is provided below.

3 TRACHEOTOMY AND TUBE-DEPENDENTTRACHEOSTOMY

‘Standard tracheotomy’ might be performed in situations in which the duration of cannulation is not expected to exceed several days. These tracheotomies might be performed in OSA if they are used to temporarily securethe airway while other upper airway surgery performed. Even then, the technique may require modifications such as lipectomy or resort to specially designed and constructed tubes in order to be safe and effective. Once postoperative edema is resolved and the risk of perioperativehemorrhage and any other problems have been overcome, the tracheotomy tube may be withdrawn and the tracheo-tomy site allowed to heal by secondary intent. If prolonged cannulation is expected, such ‘standard tracheotomy’ (even when modified) is not the procedure of choice. Patientswith severe obstructive sleep apnea are prone to develop more serious complications as they often have short, thick necks and high incidence of anatomic deformations. Chondritis, granulation tissue, infection, and stenosis make long-term maintenance of a ‘temporary standard tracheo-tomy’ undesirable.2

Techniques for ‘permanent’ tracheostomy were developed in order to minimize these complications whenever cannulation is expected to be prolonged.3 Among the several indications for establishment of a ‘permanent’ skin-lined tracheostoma are severe laryngeal or laryngotracheal stenosis, bilateral vocal cord fixation (conditions that may cause OSA in and of themselves), neurologic conditions such as myasthenia gravis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and, of course, severe OSA. The first report of permanent tracheostomy for the management of pulmonary disease was by Penta and Mayer4 in 1960; the technique was subsequently popularized for OSA by Fee and Ward5 in 1977. These techniques aim to decrease the length of the tracheocutaneous tract and bring the margins of the tracheal fenestration into direct contact and continuity with the cervical skin. Shortening the skin-to-trachea tract limits granulation tissue within the wound bed, promotes primary healing of the mucocutaneous junction, inhibits stomal stenosis, and aims to limit other complications associated with prolonged tracheotomy.

There are several techniques for creating a ‘permanent’ tracheostoma depending upon the degree of continuity established between the trachea and the cervical skin. One early method for creation of a permanent tracheostomy was the Bjork flap, in which an inferiorly based tracheal flap (generally created from the anterior portion of the second or third tracheal ring) is sutured to the inferior skin margin.6 Use of this flap relative to standard tracheotomy reduced rates of accidental decannulation and facilitated re-insertion of a displaced tracheotomy tube.7 Later methods for tracheostomy attempted to further improve the primary attachments between the trachea and the skin. An example is the ‘H-flap’ technique described by Mickelson.2 By mobilizing both cervical skin and tracheal flaps, a fully circumferential stoma is created through this technique.

4 REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE ON THEEFFICACY OF TRACHEOTOMY ANDTRACHEOSTOMY IN OSA

Once successfully performed, tracheotomy or tracheo-stomy should provide secure and complete bypass of any ventilatory obstruction proximal to the tracheotomy’s point of entry into the trachea. This achievement is unmatched by any other form of therapy for OSA. In one study, for instance, tracheostomy successfully relieved OSA in 24 patients; 22 of these patients had already failed other treatment modalities.8 Nor does the efficacy of tracheostomy fade with time, provided that local tracheal complications are avoided. A retrospective review of 79 patients with tracheostomies for OSA reveals that, even with a mean follow-up of over 8 years, tracheostomy eliminated the obstructive component in OSA in all cases.9 Long-term follow-up suggests that tracheostomy improves parameters such as Apnea/Hypopnea Index, snoring, and excessive somnolence with efficacy unmatched by any other therapy.10

Another benefit of tracheostomy is the immediacy with which it cures OSA. Obstruction is relieved soon after the tracheostomy is established. Polysomnographic measures of sleep architecture reveal that delta-wave and REM sleep are greatly increased soon after tracheotomy, in a ‘rebound’ phenomenon in which the body attempts to replenish those stages of deep sleep lost to apneic episodes.2 Within 1 month following tracheostomy, normal sleep architecture is returned; within weeks after tracheostomy, patients experience resolution of daytime sleepiness and snoring.11 In association with these improved sleep parameters, Guilleminault et al. also found that tracheostomy resolved the personality changes, erratic behavior, enuresis, morning headache, sleepwalking, and other symptoms related to OSA.12

Other studies demonstrate the effectiveness of tracheo-stomy in reducing the mortality associated with OSA. He et al. found that in patients with apnea indices >20, the 38% 8-year mortality of untreated patients was reduced to 0% in 33 patients with tracheostomy.13 Partinen et al. report similar findings in their cohort of 198 patients, 71 treated with tracheostomy and 127 treated conservatively with weight loss.14 All deaths at 5 years were in the weight loss group with a 5-year mortality rate of 11% as compared to 0% for tracheostomy. These differences in mortality are even more remarkable given that the tracheostomy group had, on average, higher apnea and body mass indices than the comparable weight loss group.

One early study on tracheostomy and hemodynamic changes in OSA was published by Motta et al. in 1978.11 Comparing patients with OSA before and after tracheo-stomy, these investigators found that during sleep, mean pulmonary and femoral artery pressures were significantly reduced following tracheostomy, while arterial oxygen levels were increased. Although the underlying mechanisms of increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are not entirely understood, one postulated etiology is that repeated hypoxic events in OSA initiate oxidative stress, cause endothelial cell dysfunction, and exacerbate atherogenic injury.15

Unfortunately, there are some limits to the effectiveness of tracheostomy for treatment of sleep apnea. First, tracheostomy can successfully treat only obstructive sleep apnea; central apnea may continue to be a problem for these patients. Indeed, one case report even describes the obstructive apneas corrected by tracheostomy being replaced by central events of similar duration and severity.16 Second, tube-dependent tracheostomy can only provide effective bypass of upper airway obstruction as long as the tube remains patent. In a patient with a large body habitus, excess soft tissue or skin folds over the chest and under the chin may actually obstruct the tube’s proximal end. It is for that reason that some authors recommend specially designed tubes in addition to adequate lipectomy in combination with tracheostomy for obese patients.17 Misalignment between the tube and the trachea may result in impaction of the tube’s caudal end against the tracheal wall, causing local ridge formation or stenosis, both of which may be compounded by traumatic suctioning. Unfortunately, patients with OSA compounded by cardiopulmonary decompensation may be more prone to complications including infections and even persistent apnea following tracheostomy (from central events, stenosis or tube obstruction) than patients with ‘uncomplicated’ OSA.18

5 COMPLICATIONS OF TUBE-DEPENDENTTECHNIQUES (TRACHEOTOMY OR TUBE-DEPENDENT TRACHEOSTOMY)

The complications of tube-dependent tracheotomy/tracheo-stomy can generally be divided into short-term and long-term categories. Short-term complications include possible intraoperative consequences such as damage to the great vessels, injury of the tracheo-esophageal party wall, pneumothorax, and pneumomediastinum. Early postoperative consequences of tracheotomy such as tube obstruction, tube displacement, and infection can also be considered short-term complications. Among the long-term complications are such problems as deep tissue infection, granulation tissue and laryngeal and/or tracheal stenosis at the stomal level or at the caudal end of the tube with predisposition to tracheo–innominate artery fistula. In addition to these physical complications, the often persistent morbidity associated with tube-dependent tracheostomy may have emotional consequences (such as depression) as well, for both the patient and the patient’s family.12,19

Several studies have documented the incidence of short-term complications following tracheotomy/tracheostomy for OSA. Thatcher and Maisel’s review of 79 patients counts four instances of peristomal wound infection, four instances of skin flap necrosis, and one fatal episode of cardiac arrest among early complications.9 Harmon et al. report a 15% incidence of peristomal infection following tracheostomy for OSA,20 while Guilleminault et al. suggest that the incidence of low-grade infection causing peristomal granulation may be closer to 42%.12 This same group also reports that a similar percentage (42%) of patients experienced early problems with poorly fitted tracheotomy tubes, such that the tube would become obstructed when the patient’s head was flexed, hyperextended or turned to the side.

Postobstructive pulmonary edema has been commonly reported following relief of short-term upper airway obstruction, such as that found with postoperative laryngospasm.21 However, postobstructive pulmonary edema has also been described as a consequence of OSA, perhaps secondary to effects of OSA on the heart and pulmonary vasculature.22 Given that tracheostomy for severe OSA provides immediate relief of prolonged upper airway obstruction, it should not be surprising that postobstructive pulmonary edema has been described in this setting as well. Comparing 45 OSA patients to 25 non-OSA patients, Burke et al. found an incidence of pulmonary edema of 67% in the OSA group following tracheotomy as compared to a control group incidence of 20%.23 While most OSA patients with post-tracheotomy pulmonary edema were graded as ‘mild’, 8/30 patients with pulmonary edema were graded as ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ and two patients (7% of the overall OSA group) died of complications related to cor pulmonale in the post-tracheotomy period.

Among long-term complications of tracheostomy, tracheo–innominate artery fistula is the most feared. Though rare (only one of 79 patients in Thatcher and Maisel’s study9), it carries a mortality rate of 73%. One controllable factor which might predispose towards fistula is a ‘too low’ tracheotomy, and for this reason, tracheotomy is rarely performed beneath the third tracheal ring. Unfortunately, emphysematous, barrel-chested, or overweight OSA patients may have a high innominate artery, mandating modifications in the surgical procedure that may promote additional damage, to the larynx in particular.

A much more common long-term complication of tracheostomy is progressive, tube-related deformation of the trachea itself, including the development of laryngotracheal stenosis. Estimates of long-term tracheal damage following tracheostomy for OSA vary and depend on the surgical technique and endpoint used in each study. For instance, Conway et al.19 reported on eight patients with standard tracheotomy and found that seven (87.5%) experienced tracheal granuloma or stomal stenosis. Among eight patients (five revision, three primary) with skin-lined permanent tracheostomy, the incidence of tracheal complications decreased to 25%. Thatcher and Maisel do not record the overall proportion of patients who developed granulation tissue, but document that eight of 79 (10%) of their cohort needed to return to the operating room for management of this problem.9

Such retrospective studies might underestimate the degree of structural laryngotracheal deformities, infections, chondritis, granulation tissue and stenosis compared to prospective studies. Law et al. review several studies and find that retrospective reviews report obstructive tracheal lesions at rates of 1–11%, while prospective studies find obstructive lesions in 20–64% of patients with long-term tracheostomies.24 Their own study of 81 patients with long-term tracheotomy (mean duration 4.9 months) utilizing fiberoptic bronchoscopy prior to decannulation discovered obstructive lesions in 54 patients (67%). Of these 54 patients with tracheal obstruction secondary to prolonged tube-dependent tracheotomy, almost half (23 of 54, 43%) had more than one type of obstructing lesion. All of the lesions were located above the level of the stoma, and included 45 obstructing tracheal granulomas (all from the anterior tracheal wall), 19 patients with tracheomalacia, and 10 episodes of tracheal stenosis.

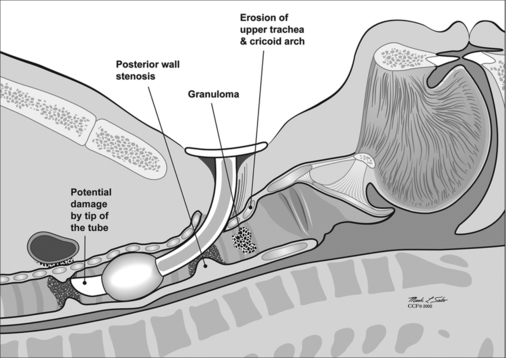

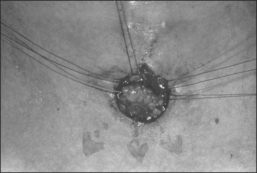

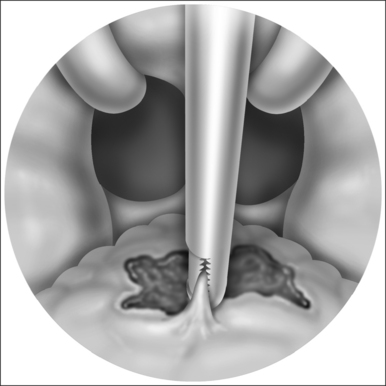

Unfortunately, damage to the trachea and larynx above the level of the stoma is too commonly an unavoidable consequence of prolonged cannulation with a curved tracheotomy tube. The introduction of a mismatched curved foreign body (the routinely used tracheotomy tube) into an otherwise straight airway displaces the suprastomal portion of the anterior tracheal wall inwards (Fig. 56.1). This pathologic buckling of the trachea is an unrelenting dynamic process perpetuated by the movements of the tube relative to the trachea during coughing, breathing, swallowing, and manipulation of the tube for cleaning. In this fashion, progressive deformation of the trachea can erode the anterior superior tracheal wall and lead to suprastomal inflammation, infection, granulation, perichondritis, chondritis and eventually necrosis, potentially extending to the cricoid arch and conus elasticus. When the tube is withdrawn, various degrees of tracheomalacia and tracheal stenosis may occur. Variations of standard tracheotomy tubes (i.e. tubes that are narrower, smoother, softer, more flexible, shorter, etc.) can help reduce but cannot eliminate the laryngotracheal morbidity associated with prolonged cannulation.25

6 TUBE-FREE TRACHEOSTOMY

6.1 EVOLUTION OF LONG-TERM TUBE-FREE TRACHEOSTOMY

Commitment to minimize the serious consequences of tube-induced damage and its complications prompted extensive research and efforts that brought forward the concept of long-term tube-free tracheostomy (LTTFT) as an alternative to tube-dependent tracheostomy.26 A case report by Eliashar et al. in which an OSA patient with an existing tube-dependent tracheotomy is revised to a LTTFT typifies the efforts to minimize the tube-induced complications of long-term tracheotomy and/or tracheostomy.27 The permanently tube-free patent stoma acquired the descriptive nickname ‘third nostril’. LTTFT is currently our recommended procedure of choice for severe and refractory OSA, as well as for other indications which require prolonged tracheostomy.

Just as tube-dependent techniques progressed from standard tracheotomy to the inferiorly based Bjork flap to fully circumferential skin-lined ‘permanent tracheostomies’, so did long-term tube-free tracheostomy evolve out of previous techniques. The procedure of LTTFT currently practiced by us is not the first tube-free technique to be described. For instance, three of the four patients described by Fee and Ward in 1977 could have been managed without tracheostomy tubes.5 However, early descriptions of tube-free techniques generally employed plugs, stents or other prostheses to enable speech during daytime even as they maintained a tube-free stoma at night.28–30 In the staged development leading to the current procedure of LTTFT, the senior author almost routinely applied specially designed Eliachar/Hood stoma stents, often with attached speaking valves, to support the patency of the stoma.31 This use of a stent, with or without a speaking valve, was practiced in all but seven patients who underwent flap-tracheostomy by the senior author prior to 1992. Of the seven tube-free patients in this group who did not require a stoma stent, five used finger occlusion of their stomata to produce speech and cough. The remaining two patients developed the ability to intentionally constrict the neck muscles around the stoma, temporarily closing it in a voluntary and timely fashion to divert airflow from the stoma through the glottis with ample volume, pressure, and velocity to produce audible voice and almost normal speech. They also succeeded in producing an effective cough which enabled them to clear secretions through the glottis rather than out of the stoma.

These two patients with volitional stoma closure formed the impetus for deliberate establishment of a truly tube-free speech-ready technique. They clearly enjoyed higher levels of function and comfort than those patients who required use of a stoma stent. The absence of tubes and prostheses in these patients reduced local irritation and improved management of secretions at the same time that it practically eliminated almost all the morbid symptoms and/or complications from tracheostomy. Because of this experience, a prospective study was designed in an effort to intentionally create long-term, tube-free, speech-ready tracheostomata in 35 patients from 1992 to 1999.26 As a consequence of successful outcomes of this study, the updated surgical technique for establishment of speech-ready LTTFT has been routinely employed in over 100 more patients since that time.

6.2 TECHNIQUE OF SPEECH-READY, LONG-TERM TUBE-FREE TRACHEOSTOMY

As is the case with most surgical procedures, the technique of speech-ready LTTFT is best performed primarily in patients without previous tracheostomies. A relatively more difficult revision procedure may be applied in patients with pre-existing tube-dependent tracheotomies or tube-dependent tracheostomies. The technique has been described comprehensively in previous articles.26 Preoperatively the patient’s medical condition, prognosis and surgical risks are thoroughly assessed. Flexible bronchoscopy and computed tomography scans with reconstituted sagittal and coronal images contribute to the surgical planning. Additionally, assessing the depth of the trachea relative to the sternal notch with the head both flexed and extended can determine appropriate levels for both intraoperative intubation and the physiologically correct placement of the tracheal fenestration. While this examination may be performed in the office, preoperative endoscopic evaluation in the operating room can be an invaluable tool for satisfactory surgical outcome. The procedure should be thoroughly co-ordinated with the patient’s primary managing physicians and the anesthesiologists, covering topics such as the required deep intubation and the need for an extra-long endotracheal tube that will position the cuff deep to the site of the intended fenestra. Plans must be made for possible postoperative consequences such as pulmonary edema and provisions arranged for the immediate availability of specially modified precurved endotracheal tubes needed for safe, atraumatic postoperative management. On the operating table, the patient’s neck should not be over-extended to ensure physiologic placement of the stoma.

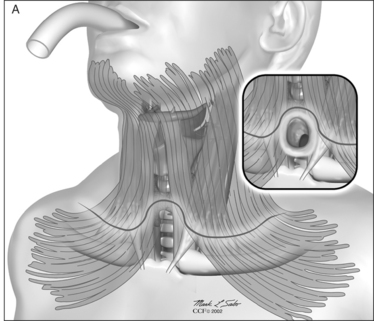

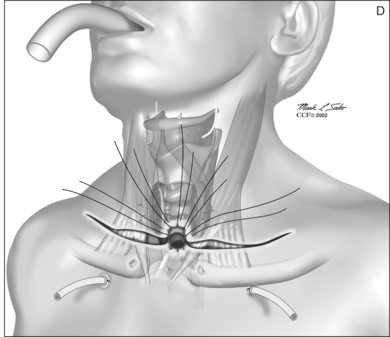

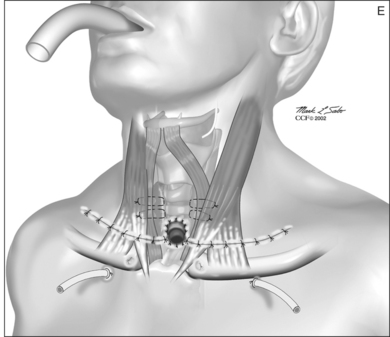

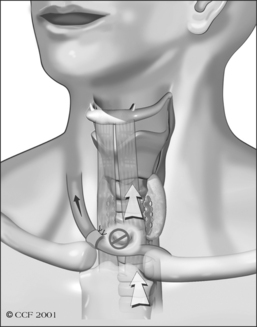

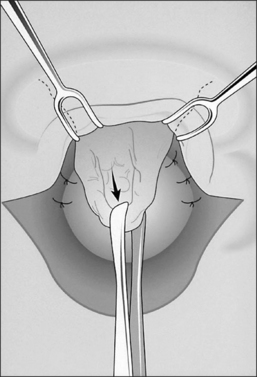

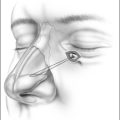

The procedure itself involves a wide horizontal omega-shaped skin incision with the horizontal limbs located approximately a centimeter superior to the clavicles, extending beyond the sternocleidomastoid muscle laterally(Fig. 56.2A). The ‘dome’ of the omega reaches up to the level of the cricoid arch in the moderately extended neck. This skin incision is carried through the platysma muscle, and subplatysmal flaps are widely undermined in all directions. To achieve full mobilization of the flaps, it is often required to extend the dissection and undermining beyond the margins of the sternocleidomastoid muscles laterally and beneath the sternum caudally.

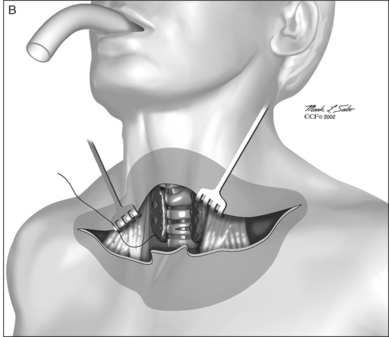

The dissection continues by separating the strap muscles in the midline (Fig. 56.2B). Similarly, the isthmus of the thyroid gland is divided or excised and the lobes are suture-ligated for hemostasis. The next crucial step is to laterally mobilize and dissect the thyroid lobes off the anterolateral surface of the trachea. By everting the strap muscles and thyroid lobes and then suturing their medial free margins laterally to the sternal tendon of the sternocleidomastoid muscles, a wide trough can be created in the midline so that the skin may be easily mobilized and brought into direct continuity with the tracheal fenestration without any interposing tissue in the way.

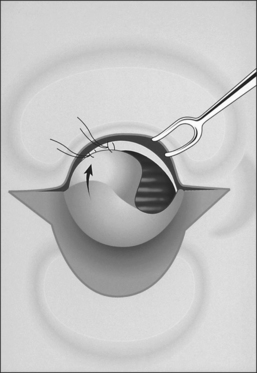

A superiorly based flap is created from the anterior tracheal wall, based upon the second and third or third and fourth tracheal rings. This superiorly based tracheal flap complements the design of the inferiorly based skin flap created through use of the omega skin incision. Excess submental fat is trimmed subplatysmally throughout the upper surgical field. The tracheal flap can thus be elevated superiorly in such a fashion as to maintain stomal patency. Meanwhile, excess fat is also trimmed from the undersurface of the inferior peristomal skin flaps so that they can be fully mobilized as well. Care must be taken during the subplatysmal excision of the adipose tissues to avoid compromise of the vascular supply to the skin flaps. Monopolar cautery is used sparingly, as bipolar cautery may reduce collateral tissue damage. Suspension stay sutures placed bilaterally between the inferior skin flap and the tendons surrounding the sternoclavicular joints can help to advance this flap superiorly and facilitate adaptation to the tracheal fenestra for tension-free closure (Fig. 56.2C). Suction drains are placed bilaterally. The tracheal fenestration and margins of the skin flaps are brought together with vertical mattress sutures in order to create a secure skin-tight circumferentially lined stoma (Fig. 56.2D). The superiorly based tracheal flap itself is surrounded by the superior skin flap, while the omega portion of the inferior skin flap is extended tension free to reach the inferolateral aspects of the tracheal fenestration. The overall effect is to create a continuous, airtight, circumferential, tension-free mucocutaneous junction which will mature by primary intent into a secure, patent tube-free stoma with a short tracheocutaneous tract (Fig. 56.2E).

Postoperative care of the suture line and the stoma must be frequent, thorough, careful and routinely performed in order to promote complete healing and aid stoma maturation. Every few hours, trained nurses, employing sterile approach and avoiding the use of tissue irritants such as hydrogen peroxide, remove crusts, gently suction, and apply protective antibiotic ointment to the peristomal suture line. The modified pre-curved, postoperative tube provides secure ventilation during the crucial first postoperative hours. This tube should be removed (unless otherwise indicated) by the end of the first postoperative day, and under no circumstances should a conventional tracheotomy tube be placed through the tracheostoma as it heals. Drains may be removed as necessary. Lateral skin sutures (from the horizontal aspects of the skin incision) can be removed one week postoperatively. Peristomal sutures should be maintained for 10 days or longer, depending upon stoma maturation. After several days in the hospital, the patient and patient’s family are trained and encouraged to assume responsibility for stoma care. Home nursing care is provided, and the patient is closely monitored for the first several postoperative weeks as it becomes clear whether the stoma will remain patent or stenose. All efforts are made to maintain the stoma without a tube or stent. It is our experience that once a tube or stent is placed during the healing process, the resulting physical deformation andforeign body-induced inflammatory effects may render its later removal difficult or impossible. In the series of35 patients with LTTFT published in 2000, all patientswere managed in a truly tube-free fashion.26 At present, we consider use of a stent or tube to be a relatively infrequent and short-lived perioperative setback which is usually encountered predominantly in conversion and in revision cases.

6.3 BENEFITS OF LONG-TERM, TUBE-FREE, SPEECH-READY TRACHEOSTOMY

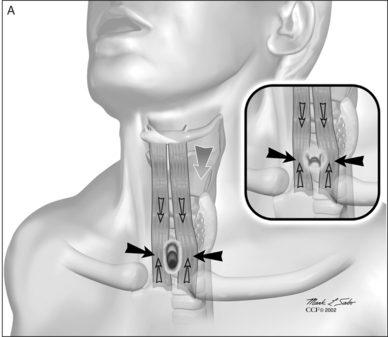

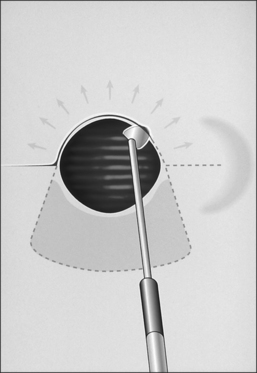

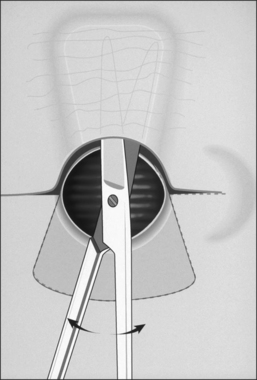

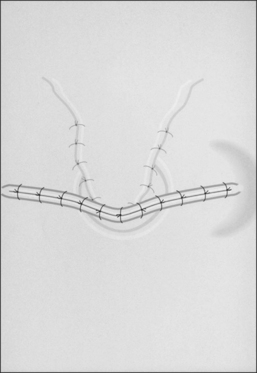

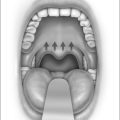

As patients achieve more control over their stomata, they may also enjoy the benefits of hands-free speech and cough. Although originally conceived as a passive ‘third nostril’ which maintains patency and provides bypass of upper airway obstruction, speech-ready LTTFT has been found to function more as an active ‘second mouth’ by enabling most patients to voluntarily close their stoma. In this mode, the stoma is opened for ventilation and is closed for speech and cough (Fig. 56.3A&B). Closure of the stoma diverts expiratory airflow through the native larynx and upper airway so that these tasks can be accomplished without the use of prostheses or finger occlusion.

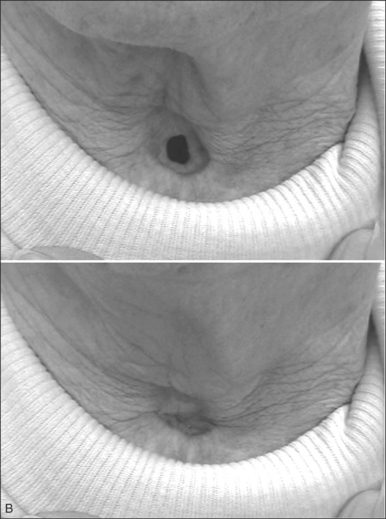

Beyond the benefits of hands-free and prosthesis-free speech and cough, long-term tube-free tracheostomy also offers easier hygiene than tube-dependent tracheotomy/tracheostomy. When nocturnal assisted ventilation is required, patients or family members can easily insert a designated well-tolerated tube through the stoma. Otherwise, there is no need for routine maintenance or care of a tracheotomy tube, suctioning is rarely necessary, and no special nursing care is required. Patients are able to clean their stoma much as they would clean their nostrils and are freed from the responsibility of carrying the burdensome equipment upon which their life might have depended were they maintained with curved tracheotomy tubes. In many ways, switching from a tube-dependent tracheotomy to LTTFT tracheo-stomy allows patients to regain mobility and freedom along with improved function; together, these changes can improve morale and quality of life. Anecdotally, improved quality of life has certainly been the much appreciated experience of those patients who have been revised from a tube-dependent tracheotomy to a LTTFT. For patients with LTTFT, a turtleneck shirt or a bib worn over the stoma may be the only clue to alert an astute observer to the presence of a successful tube-free stoma.

6.4 THE SUPPLEMENTARY SLING PROCEDURE

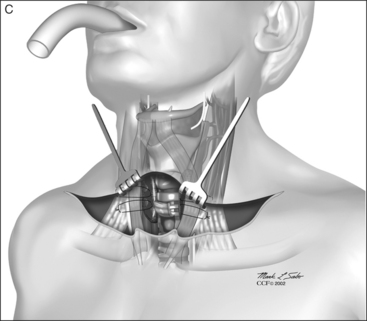

In order to divert the flow of air through the larynx rather than the stoma, and thus generate audible hands-free speech and cough, stomal closing pressures must exceed translaryngeal resistance. The ability to volitionally close a stoma sufficiently to direct flow through the larynx and upper airway is a skill that most patients learn innately, though some need encouragement or special exercises. Occasionally, either local muscle weakness or scarring may lead to inadequate voluntary stomal constriction. Also, fixed laryngotracheal stenosis above the stoma, bilateral vocal cord fixation or upper airway obstruction (as found in patients with OSA) may increase upper airway resistance. In these settings where laryngeal resistance exceeds stomal closure, attempts to generate unaided speech encounter a variable degree of air leakage through the intentionally constricted stoma. For these patients, an auxiliary second surgical procedure called the supplementary sling procedure may be performed several months after establishment of the tube-free stoma.32 (The sling procedure should never be performed before the tube-free stoma is completely mature.) This procedure repositions neck tendons and muscles in order to help these particular patients to improve stoma closure. The sling procedure has been instrumental in helping to achieve more effective stoma closure with improved voice and tracheal clearance in almost all patients with tube-free stomata who have required this further intervention (Fig. 56.4). Of the 80 LTTFTs performed since 2002, only 22 patients required the sling procedure to gain more effective volitional stomal closure.

7 TRACHEOSTOMY CLOSURE

The decision to close a tracheostomy must be made very carefully. If a stoma is closed inappropriately, the patient might experience recurrence of OSA. Therefore, closure becomes appropriate only if other surgery, weight loss, or compliance with CPAP can effectively control OSA in lieu of tracheostomy. The degree of OSA which might be present following tracheostomy closure can be assessed by performing polysomnography with the tube plugged or the stoma seal-taped. Thorough endoscopic and, if needed, radiologic examinations must rule out signs of potential laryngotracheal stenosis before closure. Recent studies document the significant effect that gastric bypass may have upon weight loss and subsequent tracheostomy closure in patients with OSA.33,34 Despite these advances, long-term studies with large numbers of patients demonstrate thatrelatively few patients with tracheostomy for OSA everhave their stomata closed – 16 of 79 patients for Thatcher and Maisel,9 and only four of 50 patients for Guilleminault et al.12

Mickelson and Rosenthal35 studied two techniques for closure of skin-lined tracheostomata in 76 patients. Those patients managed with wide undermining and then three-layer closure of the strap muscles and soft tissue overlying the trachea enjoyed good cosmetic results, but 30% of patients experienced complications such as subcutaneous emphysema, stridor, and tracheal granuloma in the immediate post-closure period. An alternative technique, termed ‘de-epithelialization’, involves decannulation one week prior to planned surgery in order to let the stoma narrow. Epithelium is then excised down to the trachea without undermining, deep tissues are loosely approximated, and no skin sutures are used. This technique is less cosmetically desirable than formal three-layer closure, but complications are reduced.

For LTTFT, there is no tube to begin with, and therefore no possibility that the stoma will narrow down and seal shut after decannulation as described above. Therefore, closure of LTTFT may require a more involved surgical technique. Our technique, which effectively closes LTTFT with minimal complications, combines a turn-over flap, medialization of fibroadipose tissue, and skin closure with an advancement flap.36 This approach can be performed under either general or local anesthesia, and it balances functional and cosmetic results (Fig. 56.5A–H).

8 PEDIATRIC TRACHEOSTOMY AND OSA

Sleep apnea has different presentations and manifestations in children than in adults. For young children, it is less a consequence of elevated Body Mass Index than it is a result of congenital syndromes. For example, craniofacialabnormalities may co-exist with obstructive apnea as a consequence of macroglossia, retrognathia or micrognathia. Also, neurological syndromes may cause abundant central or obstructive apneas. In either case, tracheostomy can be truly life-saving.37 Given size constraints and the soft flexibility of the skin in the early pediatric age group, tube-free techniques are not recommended in the pre-teen pediatric population. Instead, a preferred pediatric tracheostomy technique is ‘starplasty’, named for the fashion in which a circumferential tracheocutaneous fistula is created.38 This fistula is then maintained with a traditional pediatric tracheotomy tube. After age 12, LTTFT may be a viable option.

Unfortunately, long-term pediatric tracheotomy dependence can have severe medical and emotional consequences. In appropriate patients, aggressive surgery (craniofacial skeletal expansion, mandibular distraction, etc.) can help to either avoid tracheostomy altogether or speed decannulation.39,40 Such surgery may yield improved quality of life relative to tracheostomy in children with OSA.41

1. Kuhlo W, Doll E, Franck MD. Erfolgreiche behandlung eines Pickwick-syndroms durch eine dauertrachealkanule. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1969;94:1286-1290.

2. Mickelson SA. Upper airway bypass surgery for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otol Clin North Am. 1998;31:1013-1023.

3. Eliachar I, Zohar S, Golz A, et al. Permanent tracheostomy. Head Neck Surg. 1984;7:99-103.

4. Penta AO, Mayer E. Permanent tracheostomy in the treatment of pulmonary insufficiency. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1960;69:1157-1169.

5. Fee WE, Ward PH. Permanent tracheostomy: a new surgical technique. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86:635-638.

6. Bjork VO. Partial resection of the only remaining lung with the aid of respirator treatment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1960;29:179-188.

7. Weissler MC. Tracheotomy and intubation. In: Bailey BJ, editor. Head and Neck Surgery–Otolaryngology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:677-689.

8. Katsantonis GP, Schwitzer PK, Branham GH, et al. Management of obstructive sleep apnea: comparison of various treatment modalities. Laryngoscope. 1998;98:304-309.

9. Thatcher GW, Maisel RH. The long-term evaluation of tracheostomy in the management of severe obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:201-204.

10. Ledereich PS, Thorpy MJ, Glovinsky PK, et al. Five-year follow-up of daytime sleepiness and snoring after tracheotomy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. In: Chronic Rhonchopathy. Chouard CH, ed. Proceedings of the 1st International Congress on Chronic Rhonchopathy. Paris: Libbey Eurotext; 1988, pp. 354–7.

11. Motta J, Guilleminault C, Schroeder JS, et al. Tracheostomy and hemodynamic changes in sleep-induced apnea. Ann Intern Med. 1978;89:454-458.

12. Guilleminault C, Simmons FB, Motta J, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and tracheostomy. Long-term follow-up experience. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:985-988.

13. He J, Kryger M, Zorick J, et al. Mortality and apnea index in obstructive sleep apnea: experience in 385 male patients. Chest. 1988;94:9-14.

14. Partinen M, Jamieson A, Guilleminault C. Long-term outcome for obstructive sleep apnea patients: mortality. Chest. 1988;94:1200-1204.

15. Lavie L. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome – an oxidative stress disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:35-51.

16. Fletcher EC. Recurrence of sleep apnea syndrome following tracheostomy: a shift from obstructive to central apnea. Chest. 1989;96:205-209.

17. Gross ND, Cohen JI, Anderson PE, et al. ‘Defatting’ tracheotomy in morbidly obese patients. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1940-1944.

18. Kim SH, Eisele DW, Smith PL, et al. Evaluation of patients with sleep apnea after tracheotomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:996-1000.

19. Conway WA, Victor LD, Magilligan DJ, et al. Adverse effects of tracheostomy for sleep apnea. JAMA. 1981;246:347-350.

20. Harmon JD, Morgan W, Chaudhary B. Sleep apnea: morbidity and mortality of surgical treatment. South Med J. 1989;82:161-164.

21. McConkey PP. Postobstructive pulmonary oedema – a case series and review. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2000;28:72-76.

22. Chaudhary BA, Nadimi M, Chaudhary TK, et al. Pulmonary edema due to obstructive sleep apnea. South Med J. 1984;77:499-501.

23. Burke AJC, Duke SG, Clyne S, et al. Incidence of pulmonary edema after tracheotomy for obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:319-323.

24. Law JH, Barnhart K, Rowlett W, et al. Increased frequency of obstructive airway abnormalities with long-term tracheostomy. Chest. 1993;104:136-138.

25. Eliachar I, Papay FA. Laryngotracheal devices. In: Krespi J, Ossuf R, editors. Complications in Head and Neck Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993:233-256.

26. Eliachar I. Unaided speech in long-term tube-free tracheostomy. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:749-760.

27. Eliashar R, Goldfarb A, Gross M, Sichel JY. A permanent tube-free tracheostomy in a morbidly obese patient with severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:1156-1157.

28. Weitzman E, Pollak C, Borowiecki B, et al. The hypersomnia–sleep apnea syndrome: site and mechanism of upper airway obstruction. In: Guilleminault C, Dement W, editors. Sleep Apnea Syndromes. New York: Allan R. Liss Corporation, 1978.

29. Olson K, Pearson B. Sleep apnea tracheostomy. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:555-556.

30. Sahni R, Blakley B, Maisel R. Flap tracheostomy in sleep apnea patients. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:221-223.

31. Miller FR, Eliachar I, Tucker HM. Technique, management, and complications of the long-term flap tracheostomy. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:543-547.

32. Eliachar I, Akst LM, Eliashar R. Unaided speech in tube-free tracheostomy: the supplementary sling procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:213-220.

33. Scheuller M, Weider D. Bariatric surgery for treatment of sleep apnea syndrome in 15 morbidly obese patients: long-term results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:299-302.

34. Rasheid S, Banasiak M, Gallagher SF, et al. Gastric bypass is an effective treatment for obstructive sleep apnea in patients with clinically significant obesity. Obes Surg. 2003;13:58-61.

35. Mickelson SA, Rosenthal L. Closure of permanent tracheostomy in patients with sleep apnea: a comparison of two techniques. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116:36-40.

36. Eliashar R, Sichel JY, Eliachar I. A new surgical technique for primary closure of long-term tracheostomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005;B2(1):115–18.

37. Cohen SR, Lefaivre JF, Burstein FD, et al. Surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in neurologically compromised patients. Plast Reconst Surg. 1997;99:638-646.

38. Koltai PJ. Starplasty. A new technique of pediatric tracheotomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:1105-1111.

39. Cohen SR, Simms C, Burstein FD, et al. Alternatives to tracheostomy in infants and children with obstructive sleep apnea. J Ped Surg. 1999;34:182-187.

40. Williams JK, Maull D, Graytson BH, et al. Early decannulation with bilateral mandibular distraction for tracheostomy-dependent patients. Plast Reconst Surg. 1999;103:48-57.

41. Cohen SR, Suzman K, Simms C, et al. Sleep apnea surgery versus tracheostomy in children: an exploratory study of the comparative effects on quality of life. Plast Reconst Surg. 1998;102:1855-1864.

1. Chouard CH, ed. Chronic rhonchopathy. Proceedings of the 1st International Congress on Chronic Rhonchopathy. Paris: Libbey Eurotext; 1988, pp. 354–7.

2. Conway WA, Victor LD, Magilligan DJ, et al. Adverse effects of tracheostomy for sleep apnea. JAMA. 1981;246:347-350.

3. Eliachar I. Unaided speech in long-term tube-free tracheostomy. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:749-760.

4. Eliachar I, Papay FA. Laryngotracheal devices. In: Krespi J, Ossuf R, editors. Complications in Head and Neck Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993:233-256.

5. Eliachar I, Akst LM, Elaishar R. Unaided speech in tube-free tracheostomy: the supplementary sling procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:213-220.

6. Eliachar I, Zohar S, Golz A, et al. Permanent tracheostomy. Head Neck Surg. 1984;7:99-103.

8. Eliachar R, Goldfarb A, Gross M, Sichel JY. A permanent tube-free tracheostomy in a morbidly obese patient with severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:1156-1157.

9. Fee WE, Ward PH. Permanent tracheostomy: a new surgical technique. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86:635-638.

10. Gross ND, Cohen JI, Anderson PE, et al. ‘Defatting’ tracheotomy in morbidly obese patients. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1940-1944.

11. Guilleminault C, Simmons FB, Motta J, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and tracheostomy. Long-term follow-up experience. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:985-988.

12. Katsantonis GP, Schwitzer PK, Branham GH, et al. Management of obstructive sleep apnea: comparison of various treatment modalities. Laryngoscope. 1998;98:304-309.

13. Ledereich PS, Thorpy MJ, Glovinsky PK, et al. Five-year follow-up of daytime sleepiness and snoring after tracheotomy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. In: Miller FR, Eliachar I, Tucker HM, editors. Technique, Management, and Complications of the Long-term Flap Tracheostomy. Laryngoscope, 1995. 105

14. Partinen M, Jamieson A, Guilleminault C. Long-term outcome for obstructive sleep apnea patients: mortality. Chest. 1988;94:1200-1204.

15. Penta AO, Mayer E. Permanent tracheostomy in the treatment of pulmonary insufficiency. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1960;69:1157-1169.

16. Sahni R, Blakley B, Maisel R. Flap tracheostomy in sleep apnea patients. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:221-223.

17. Thatcher GW, Maisel RH. The long-term evaluation of tracheostomy in the management of severe obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:201-204.