Speech

BACKGROUND

Abnormalities of speech need to be considered first, as these may interfere with your history taking and subsequent ability to assess other aspects of higher function and perform the rest of the examination.

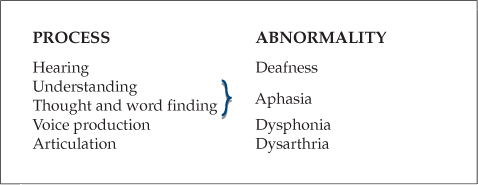

Abnormalities of speech can reflect abnormalities anywhere along the following chain shown.

Problems with deafness are dealt with in Chapter 12.

1 Aphasia

In this book, the term aphasia will be used to refer to all disorders of understanding, thought and word finding. Dysphasia is a term used by some to indicate a disorder of speech, reserving aphasia to mean absence of speech.

Aphasia has been classified in a number of ways and each new classification has brought some new terminology. There are therefore a number of terms that refer to broadly similar problems:

• Broca’s aphasia = expressive aphasia = motor aphasia

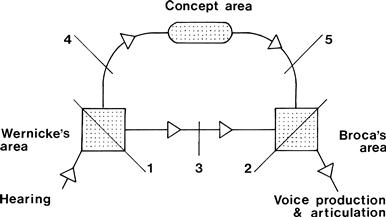

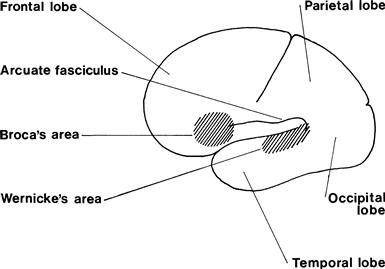

Most of these systems have evolved from a simple model of aphasia (Fig. 2.1). In this model, sounds are recognised as language in Wernicke’s area, which is then connected to a ‘concept area’ where the meaning of the words is understood. The ‘concept area’ is connected to Broca’s area, where speech output is generated. Wernicke’s area is also connected directly to Broca’s area by the arcuate fasciculus. These areas are in the dominant hemisphere and are described later. The left hemisphere is dominant in right-handed patients and some left-handed patients, and the right hemisphere is dominant in some left-handed patients.

The following patterns of aphasia can be recognised and are associated with lesions at the sites as numbered on the figure:

2. Broca’s aphasia—preserved comprehension; non-fluent speech; no repetition

3. Conductive aphasia—loss of repetition with preserved comprehension and output

4. Transcortical sensory aphasia—as in (1) but with preserved repetition

5. Transcortical motor aphasia—as in (2) but with preserved repetition

Reading and writing are further aspects of language. These can also be included in models such as the one above. Not surprisingly, the models become quite complicated!

2 Dysphonia

This is a disturbance of voice production and may reflect either local vocal cord pathology (such as laryngitis), an abnormality of the nerve supply via the vagus, or occasionally a psychological disturbance.

3 Dysarthria

Voice production requires coordination of breathing, vocal cords, larynx, palate, tongue and lips. Dysarthria can therefore reflect difficulties at different levels.

Lesions of upper motor neurone type, of the extrapyramidal system (such as Parkinson’s disease) and cerebellar lesions disturb the integration of processes of speech production and tend to disturb the rhythm of speech.

Lesions of one or several of the cranial nerves tend to produce characteristic distortion of certain parts of speech but the rhythm is normal.

1 APHASIA

WHAT TO DO

Speech abnormalities may hinder or prevent taking a history from the patient. If so, take the history from relatives or friends.

Assess understanding

Ask the patient a simple question:

If he does not appear to understand:

Test understanding

Assess spontaneous speech

If the patient does appear to understand but is unable to speak:

Ask further questions

Enquire, for example, about the patient’s job or how the problem started.

Assess word-finding ability and naming

These are tests of word finding. The test can be quantified by counting the number of objects within a standard time.

Assess repetition

Further tests

WHAT YOU FIND

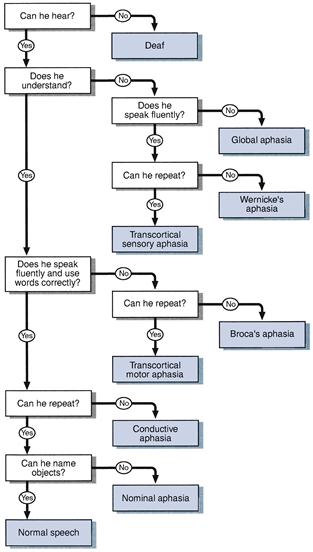

See Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 Flow chart: aphasia

Before continuing your examination, describe your findings: for example, ‘This man has a socially incapacitating non-fluent global aphasia which is predominantly expressive, with paraphasia and impaired repetition. There is associated dyslexia and dysgraphia.’

WHAT IT MEANS

• Aphasia: lesion in the dominant (usually left) hemisphere.

• Global aphasia: lesion in the dominant hemisphere affecting both Wernicke’s and Broca’s areas (Fig. 2.3).

• Conductive aphasia: lesion in arcuate fasciculus.

• Transcortical sensory aphasia: lesion in the posterior parieto-occipital region.

• Transcortical motor aphasia: incomplete lesion in Broca’s area.

Common causes are given on page 32 under Focal Deficits.

2 DYSPHONIA

WHAT TO DO

If the patient is able to give his name and address but is unable to produce a normal volume of sound or speaks in a whisper, this is dysphonia.

3 DYSARTHRIA

WHAT TO DO

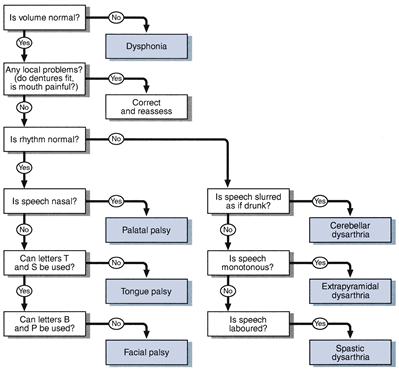

If the patient is able to give his name and address but the words are not formed properly, he has dysarthria (Fig. 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Flow chart: dysarthria

Ask the patient to repeat difficult phrases, e.g. ‘Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled pepper’ or ‘The Leith policeman dismisseth us’. Two very useful phrases are:

Listen carefully for:

WHAT YOU FIND

Types of dysarthria

With abnormal rhythm

With normal rhythm

– Palatal: nasal speech, as with a bad cold

– Tongue: distorted speech, especially letters t, s and d

– Facial: difficulty with b, p, m and w, the sounds avoided by ventriloquists.

– Muscle fatigability is demonstrated by making the patient count.

Before continuing your examination, describe your findings.

TIP

TIP TIP

TIP

TIP

TIP