Special Signs and Other Tests

In this chapter, a number of signs are described which are used on particular occasions:

1 PRIMITIVE REFLEXES

Snout reflex

What to do

Ask the patient to close his eyes. Tap his mouth gently with a patella hammer.

Palmo-mental reflex

What to do

Scratch the palm of the patient’s hand briskly across the centre of the palm and look at the chin.

Grasp reflex

What to do

Place your fingers on the patient’s palm and pull your hand away, asking the patient to let go of your hand.

What you find

What it means

All these primitive reflexes may be found in normal people. They occur more frequently in patients with frontal pathology and diffuse encephalopathy. If unilateral, they strongly suggest contralateral frontal lobe pathology.

2 SUPERFICIAL REFLEXES

Cremasteric reflex

This reflex can be performed in men. The inner aspect of the upper thigh is stroked downward. The movement of the testicle in the scrotum is watched. Cremasteric contraction elevates the testicle on that side.

Anal reflex

What to do

Lie the patient on his side with the knees flexed. Lightly stroke the anal margin with an orange stick.

What it means

This tests the integrity of the reflex arc with segmental innervation of S4 and S5 for sensory and motor components. If no contraction seen this indicated a lesion in this reflex arc. Most commonly a cauda equina lesion.

3 TESTS FOR MENINGEAL IRRITATION

Neck stiffness

What to do

N.B. Not to be performed if there could be cervical instability—for example, following trauma or in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

The patient should be lying flat.

Place your hands behind the patient’s head.

What you find and what it means

• Neck moves easily in both planes, with the chin easily reaching the chest on neck flexion: normal.

• Neck rigid on movement: neck stiffness.

– May also occur in severe cervical spondylosis, parkinsonism, with tonsillar herniation.

N.B. Proceed to test for Kernig’s sign.

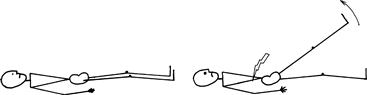

• Hip and knee flexion in response to neck flexion: Brudzinski’s sign (Fig. 25.1). This indicates meningeal irritation.

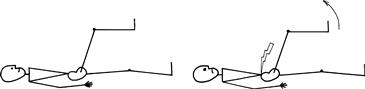

Figure 25.1 Brudzinski’s sign

Testing for Kernig’s sign

What to do

The patient is lying flat on the bed.

What you find and what it means

Head jolt test

A newer sensitive (but not very specific) test for meningeal irritation.

What to do

Ask the patient to turn his head horizontally at a frequency of two or three times a second.

4 TESTS OF RESPIRATORY AND TRUNK MUSCLES

Respiratory muscles

The intercostal muscles and diaphragm can be involved especially in neuromuscular disorders. Clinical examination can be useful in evaluating respiratory muscle weakness but is of limited value. If respiratory muscle weakness is present, or seriously considered, then physiological measures, particularly vital capacity (which may need to be done lying and standing) and inspiratory mouth pressures, are important and regular monitoring may be needed.

Testing will generally be undertaken if:

Axial and trunk muscles

These will be rarely tested formally but are tested indirectly during other elements of the examination—for example when the patient sits up unsupported or walks.

Rarely, patients can present with weakness of axial muscles, for example head drop, when the head hangs forward as a result of weakness of the cervical erector spinae, or camptocormia, when the patient flexes at the waist from weakness of thoracolumbar erector spinae.

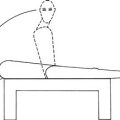

Erector spinae can be tested: ask the patient to lie on his front and lift his head up (cervical erector spinae), and then lift his shoulders up (thoracic erector spinae). Then ask him to rest down again and then lift his feet off the couch (lumbar erector spinae).

5 MISCELLANEOUS TESTS AND SIGNS

Tinel’s test

Percussion of a nerve at putative site of compression (usually using a tendon hammer). It is positive when paraesthesiae are produced in the distribution of the nerve concerned. Commonly performed to test for median nerve compression at the wrist.

Lhermitte’s phenomenon

Forward flexion of the neck produces a feeling of electric shock, usually running down the back. The patient may complain of this spontaneously or you can test for it by flexing the neck. Occasionally, patients have the same feeling on extension (reverse Lhermitte’s).

This indicates cervical pathology—usually demyelination. It occasionally occurs with cervical spondylitic myelopathy or cervical tumours.

Straight leg raising (Fig. 25.3)

Test for lumbosacral radicular entrapment.

Figure 25.3 Straight leg raising

With the patient lying flat on the bed, lift the leg, holding the heel. Note angle attained and any difference between the two sides.

Head impulse test

The vestibular ocular reflex (VOR) keeps the eyes stable when we move. If it is lacking, our vision jumps up and down like a home-made video (referred to as oscillopsia). The main inputs to this reflex come from the vestibular system in the inner ear and proprioception from the neck muscles. The information is integrated in the brainstem and leads to eye movements to balance the effect of any movement.

The head impulse test is used to examine fast VOR mediated by the lateral semicircular canal and looks at the ability of the eyes to remain stable with rapid movements. It is useful in patients with vertigo.

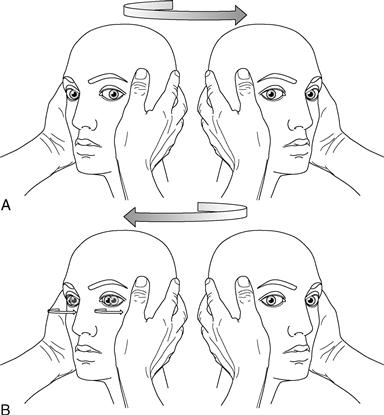

What to do (Fig. 25.4)

Sit opposite the patient.

Put your hands on either side of the patient’s head.

Gently move the head 15 degrees to the right.

Then turn the head as rapidly as possible to the left so you end up 15 degrees to the left.

Watch the eyes carefully.

Repeat, starting 15 degrees to the left and moving the head to the right.

What you find and what it means

• The eyes remain stable looking at the distant object (Fig. 25.4A): normal VOR.

• The eyes turn with the head and then have to dart back to the correct position to look at the distant vision (a corrective saccade; Fig. 25.4B): indicates a peripheral vestibular lesion on the side the head was moved towards.

The test is highly specific for peripheral vestibular lesions.

Common cause of unilateral peripheral vestibular lesions: vestibular neuritis.

TIP

TIP