CHAPTER 37 Special Rhinoplasty Techniques

Aesthetic and reconstructive rhinoplasty is considered to be the most challenging and difficult of all facial plastic procedures. Every rhinoplasty is unique and presents the surgeon with a diversity of challenges for which he or she must have a variety of specialized techniques to address each patient’s anatomic and functional deformities. This chapter addresses some of the less common nasal deformities and the surgical techniques that can be used to correct them. These deformities require the inclusion of all aspects of combined septorhinoplasty, with frequent extension and modification of several techniques.1,2 These cases are particularly challenging in regard to improving the airway and gaining maximum improvement in appearance. A form of combined septorhinoplasty to correct both the external and the internal nasal deformities in one stage is virtually essential.1–4 This chapter focuses on modifications of the septum, nasofrontal angle, and nasal tip while detailing the principles and techniques needed to correct the twisted nose, the saddle nose, the noncaucasian nose, and the cleft-lip nose.

Analysis

Coordination of the preoperative analysis with the findings at the operative table can be accomplished through either the standard intranasal rhinoplasty approaches or the external rhinoplasty approach. The authors use both the standard rhinoplasty approaches and the external approach. The external approach is particularly useful in the twisted nose, the nose requiring implant materials, and the cleft-lip nose.2,5–7

Incisions and Soft Tissue Elevation

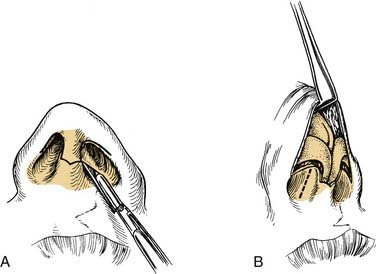

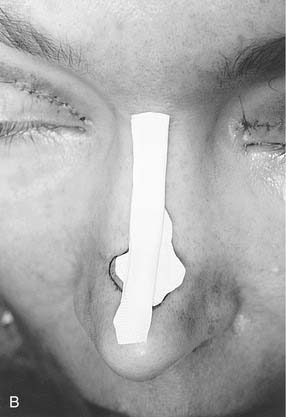

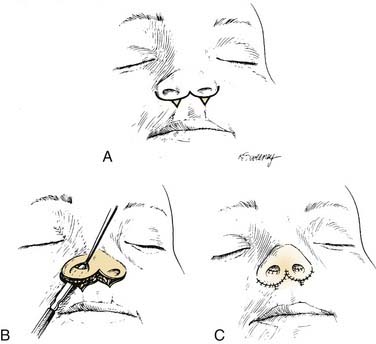

The authors generally use intranasal incisions for a deviated nose but will frequently use the open or external rhinoplasty technique when there are severe asymmetries, deviations, and tissue deficiencies.2,5–7 Some of the indications for use of the external rhinoplasty are as follows: (1) a nasal deformity that is difficult to precisely analyze; (2) one in which there is severe asymmetry of the lateral bony walls and the lower lateral cartilages; (3) when tissue deficiencies exist so that it is necessary to precisely place and suture implants in position8; (4) congenital anomalies such as the cleft-lip nose or other deformities in which profound asymmetries exist; (5) an extremely wide bony and cartilaginous dorsum, whether or not a hump is removed; and (6) for teaching purposes. The external approach involves a transverse midcolumella incision in a gull-wing curve rather than one with sharp angle. The authors use the gull-wing incision as opposed to the inverted gull-wing incision to create a single point rather than two points at the distal end of this diffuse random pattern flap. The incision is then extended upward along the caudal edge of the medial crus and laterally along the caudal margin of the lateral crus as an alar cartilage margin incision (Fig. 37-1). The elevation is initiated with sharp knife dissection, with the columella skin being elevated before the elevation is extended laterally over the lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilages. The external incision crossing the columella leaves a barely perceptible scar and offers excellent visualization by means of the “degloving” of the nose.

Septal and Columella Modifications

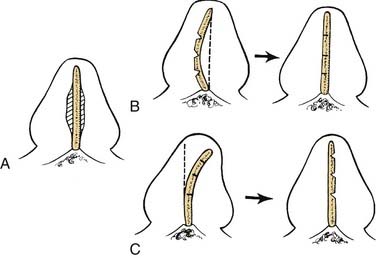

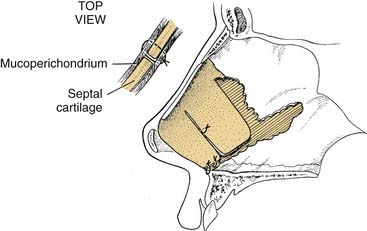

For the severely deviated or previously operated nose, it is usually necessary to elevate the mucoperichondrium on both sides of the septal cartilage, although it is preferable whenever possible to leave it attached on one side as the bone and cartilaginous angulations are corrected. Freeing fibrous contractions and septal angulations is essential in allowing the septal framework to straighten. The extent to which cartilage and bone must be removed or repositioned is dictated by the particular deformity encountered and the direction of the angulations. Generally, scoring or removal of thin strips of cartilage along the existing angulations is required to achieve straightening (Fig. 37-2). Release of all tension vectors allows a buckled septum to straighten. Determination of the final position of the septum may not be possible until osteotomies have been performed, particularly if the nasal bones and upper lateral cartilages are severely deviated from the midline. A final determination of what more, if anything, needs to be done to the septum, therefore, must sometimes await the completion of medial and lateral osteotomies, when the entire nose is positioned in the midline (Fig. 37-3) regarding deviations of the central bony complex).

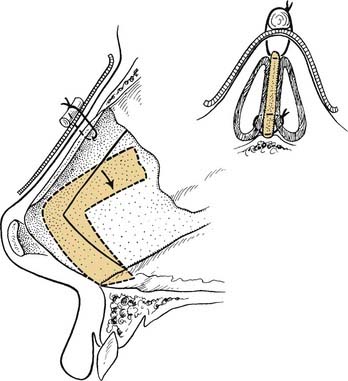

Transseptal coaptation sutures, which bring the two mucoperichondrial flaps together and pass between angulations or cartilage pedicles to prevent overlap, are great aids in this surgery (Fig. 37-4). Polyethylene splints have been used for a number of years to stabilize the septum in the early postoperative period and to prevent the development of synechiae, particularly when turbinate surgery has been performed. Two through-and-through sutures are always placed through the polyethylene splints. The sutures are placed so that one arm of the suture goes between cartilage pedicles or beneath the septal cartilage for support. The second arm of the suture goes back through the mucoperichondrium and cartilage. One may splint the septum further at a major angulation with a straight portion of thin perpendicular plate of the ethmoid.

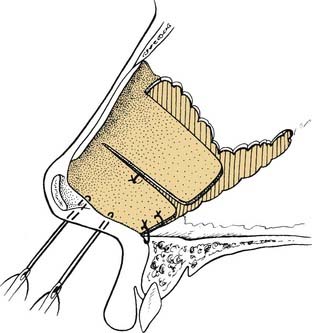

Caudal Repositioning

When it is necessary to reposition the caudal portion of the septum, it is usually necessary to free the mucoperichondrium on both sides to release all extrinsic tension on the cartilage. The septal cartilage is then detached from the underlying anterior nasal spine and maxillary crest. Intrinsic tension of the septum is relieved by scoring, cross-hatching, and wedging. Once this caudal pedicle is freed of the tension vectors, it may be maintained in the midline by sutures that go around the anterior spine or through a burr hole in the spine (Fig. 37-5). To further prevent dislocation, an additional suture may be passed through the two mucoperichondrial flaps and between the bone of the spine and the cartilage. The cartilage pedicle is attached directly to the spine for alignment, and the two mucoperichondrial flaps when sutured together add further stability. When necessary, the caudal edge of the septum may be held in proper relation to the columella with interrupted sutures or direct through-and-through septocolumellar sutures (Fig. 37-6).

Shortening the Caudal Septum

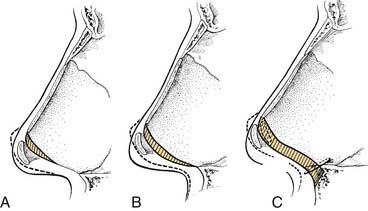

For the deformed nose with a drooping tip and columella retraction, the entire septocolumellar complex must be critically evaluated. In correcting the drooping tip, the lower lateral cartilages must be rotated cephalically, and strong tip support is needed. Both the caudal septum and the soft tissue may need modification to achieve this (Fig. 37-7). Frequently, there is an associated columella retraction, resulting in an acute nasolabial angle. Correction of the retraction requires straightening the caudal septum and placement of a columellar strut or a plumping graft (Fig. 37-8). Some limited resection of the caudal edge of the septum may be necessary to remove a portion of deformed septum that is dislocated off the anterior spine and projecting into one nostril. When the caudal edge of the septal cartilage is severely dislocated, it often creates distortion and retraction of the columella, even though adequate cartilage is present. Straightening and repositioning of the caudal septum within the columella sometimes corrects the retraction (Fig. 37-9). Rarely is it necessary to shorten the upper lateral cartilages, although reduction of the scroll along their caudal border may be necessary to reduce excessive width in that area.

Making the Final Septal Assessment

It is not until all septal reconstructive surgery and the osteotomies are completed that the final analysis of the position of the septum can be made. This position is particularly critical at the junction of the bony and cartilaginous portions of the nose, both internally and externally. At this point, the surgeon can determine whether adequate dorsal support has been maintained. If there is any tendency for the cartilaginous dorsum to sink inward, a draw suture can be passed through the skin to pick up either the septum alone or the upper lateral cartilages and the septum along the dorsum (Fig. 37-10). The suture is passed upward through the skin and held in position while all coapting and supporting sutures are placed and packing is completed. The draw suture can then be removed. In extreme cases, the draw suture can be passed through a thin external splint and tied over a bolus to remain in place for a week until the splint is removed.

The Septocolumellar Complex

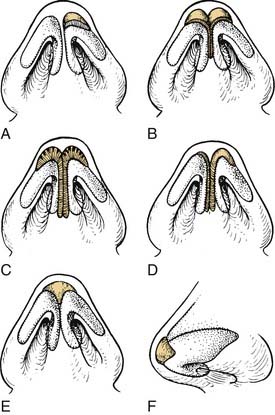

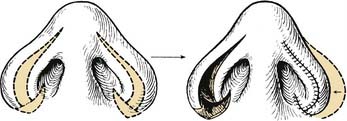

These deformities can be addressed by trimming or sculpturing the medial crura and caudal septum as demonstrated in Fig. 37-11. Other structures that may contribute to the perceived or actual abnormalities of the caudal septum and columella include either ptosis of the lateral crus of the lower lateral cartilage, causing what appears to be a retracted columella, or retraction of the ala, resulting in excessive columella show (Fig. 37-12). These abnormalities must be corrected when addressing the lower lateral cartilages, either through reduction or augmentation (Fig. 37-13). Repositioning of the anterior maxillary spine, division of the depressor nasi musculi, sectioning of the frenulum, and defatting or augmentation of the nasolabial angle may also be necessary when addressing the caudal septum and columella.9

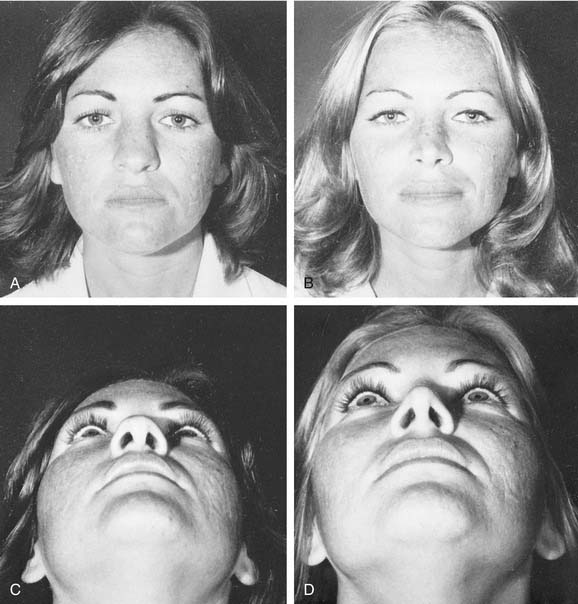

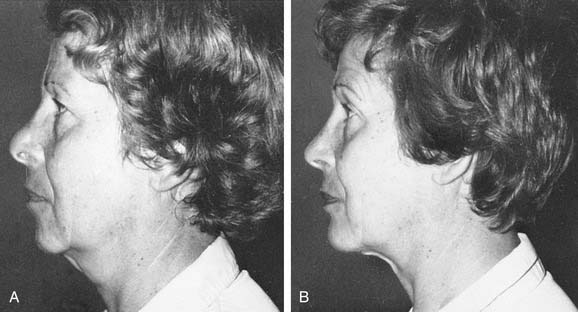

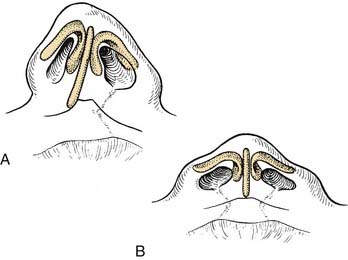

Figure 37-12. Cephalad retraction of the alar margin. A, Postoperative complications: the all-too-frequent supratip swelling or pollybeak deformity and cephalic retraction of the lateral alar margin. B, Correction is accomplished by reducing the cartilaginous nasal septum and removing supratip fibrous tissue, further sculpturing the lower lateral cartilages, freeing the lateral crus, and inserting a cartilage implant retrograde along the alar margin. (See also Fig. 37-13.)

Nasofrontal Angle Modifications

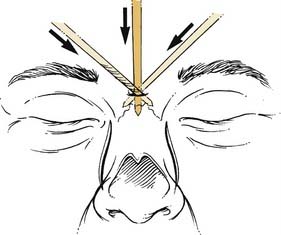

Subtle modifications in the nasofrontal angle can significantly enhance a patient’s nasal and facial profile. In patients with a shallow nasofrontal angle, the nose often appears to have excessive length. In this type of patient a 2-mm osteotome can be inserted through a stab incision in the midline over the nasal bones (Fig. 37-14). The nasal bones can be scored or weakened on either side with transverse osteotomies, thereby controlling the cephalic fracture site. This will allow the surgeon to control the site of the nasofrontal angle when the bony hump is removed. After removal, the angle may be smoothed or further deepened by the use of the rasp or rongeur.

Tip and Alar Asymmetries

Tip Grafts

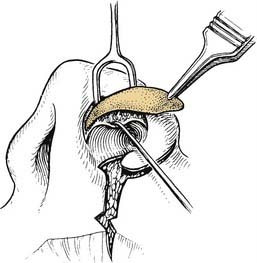

When there are severe asymmetries of the lower lateral cartilages, management usually requires modification of the more normal cartilage and the more abnormal side if one is to achieve a symmetric tip. The cephalic portion of the lower lateral cartilage is an excellent implant to be used in the nasal tip to overlie angulations, to fill small depressions, or for splinting cartilage by direct suturing. When more sturdy cartilage is necessary, sculptured or laminated septal or auricular cartilage is useful (Fig. 37-15). In the tip, these implants may be combined and sutured directly to a columella strut or to the domes of the lower lateral cartilages. If there is marked distortion with associated soft tissue contracture, it may be necessary to free the lateral crus of the lower lateral cartilage on the involved side of both dorsal and vestibular skin and then advance the lateral crus into the nasal tip between the two skin layers as in the technique used in the cleft-lip nose repair (Fig. 37-16).

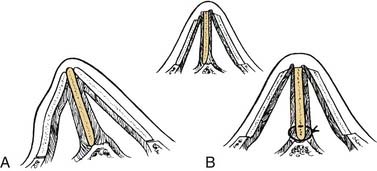

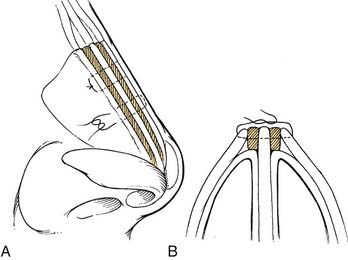

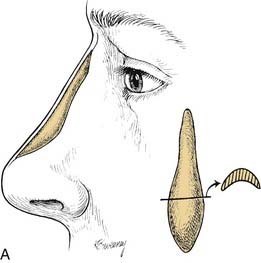

The septum is an ideal source of grafts to be placed in the nasal tip. Such an implant has the effect of stabilizing the medial crura and domes in proper relationship and giving some increased tip projection. This technique is useful in both the severely traumatized tip and the previously operated nose, in which all too often too much tissue has been removed from the lower lateral cartilages. A nasal tip graft or shield graft should be sutured directly to the lower lateral cartilages. This may be accomplished readily through intranasal incisions (alar cartilage margin incisions) or can be placed with greater ease and less chance of dislodgment through an external rhinoplasty (Fig. 37-17). Migration of the shields has been the major problem with their use, and direct suturing prevents this displacement. By removal of a wedge from the inferior border of the shield, two points are created along the inferior border, assisting in stabilization to prevent movement.

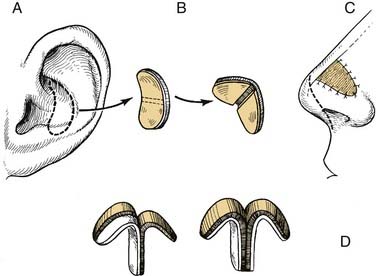

Alar Batten Grafts

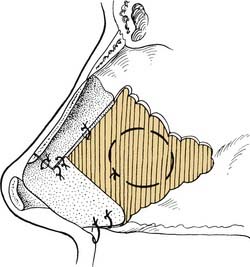

The nasal airway immediately beneath the upper lateral cartilages is of particular importance functionally. This valve area requires special consideration when there is inward collapse of the upper or lower lateral cartilages at the level of the limen vestibuli. Here it may be necessary to place cartilage implants from the auricle or the septum, shaped into an outward convexity to create a flying buttress effect. The cephalic portion of the lower lateral cartilages with its vestibular skin may be rotated into a supratip defect. Often both skin and cartilage are required, and the natural curvature of the concha of the auricle with its thin anterior skin is an ideal composite graft to use in the valve area. The graft overrides the septal cartilage, and the auricular skin of the graft is sutured to the nasal mucosa (Fig. 37-18). This composite graft is a source of support and lining for the constricted valve area.

Suture Techniques

Suture contouring of the nasal tip is a reversible and nondestructive technique that allows recontouring and repositioning of the nasal tip without structural disruption. Suture contouring is performed from “the ground up.”10,11 Multiple suture techniques allow contouring of the lower lateral cartilages. The lateral crural spanning suture, the transdomal suture, and the interdomal sutures are suture techniques that the authors commonly use to allow precise changes to be performed in a reversible manner.

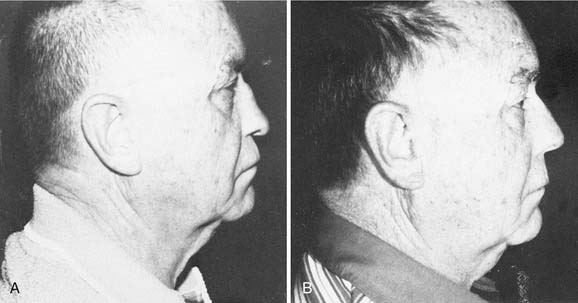

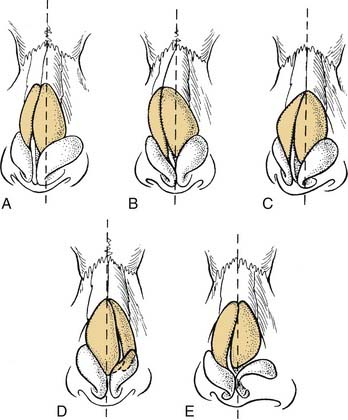

The Twisted Nose

Surgical management of the twisted nose remains one of the most difficult challenges in facial plastic surgery. The patient and surgeon should have realistic expectations to the degree of correction that can be obtained without compromising nasal support and function. To correct the twisted nose, the surgeon must determine the specific deformities that are present. A thorough nasal examination including external and internal inspection with palpation must be performed. The structural support, symmetry, and deviation of the nasal bones, the upper lateral cartilages, and the lower lateral cartilages need to be evaluated during the external examination (Fig. 37-19). The internal examination allows inspection and palpation of the septum and nasal spine. It is important to determine the position of the septum and the nasal spine relative to the midline.

Osteotomies

Before performing osteotomies to realign the nasal vault, the surgeon must determine exactly how much, if any, hump reduction should be carried out. Often in the traumatized nose, a “relative” hump is created by loss of support and flattening in the cartilaginous portion of the dorsum. In these patients, initial attention should be devoted to increasing the cartilaginous projection with combined septal surgery and nasal tip surgery.12 If the dorsal hump is to be removed, then the deviation of the bony vault must be taken into consideration. In the externally deviated nose, there is usually asymmetry of the lateral vaults, both bony and cartilaginous. This may be corrected with an asymmetric hump removal, with more bone and cartilage being removed on the longer or concave side (Fig. 37-20). In some patients, it is desirable to section the mucosa and the bone or cartilage during hump removal. This is particularly true when a large hump has been removed; the redundant mucosa beneath the dorsum can herniate upward beneath the skin and result in an undesirable dorsal fullness.

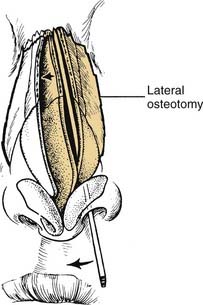

The medial osteotomies are performed first.2,12,13 If there is to be an intermediate osteotomy halfway between the medial and lateral osteotomies, it is done second. The lateral osteotomy is performed last. If there is a thick plate of bone just at the upper edge of the now-open roof, it may act as a fulcrum over which the nasal bones rock outward at the nasion as the lower border is moved medially. This wedge of bone is removed with an osteotome, with an incision being made in the plane of the septum and then in the plane of the nasal bones (Fig. 37-21).12,13 After this, the medial osteotomies are extended to the radix, either in a plane paralleling the nasal septum or curving laterally toward the position of the upper end of the lateral osteotomy. Extending the bone incision to the radix is considered the complete osteotomy and is often essential in a twisted nose, particularly if the deviation extends up to the radix (Fig. 37-22). When this is required, the osteotome is reinserted into the medial osteotomy after completion of the medial and lateral osteotomies and carried into the firm bone of the radix, where a strong fulcrum for the osteotome is developed. The osteotome is used to fracture the nasal bone and perpendicular plate of the ethmoid toward the midline. This is not an outfracturing maneuver but rather a fracturing of the central portion of the superior nasal complex to include the midline root of the nasal bones and perpendicular plate of the ethmoid (see Fig. 37-3).

In the wide flat nose in which it is not necessary to change the profile line, the flat roof of the bony vault and of the upper lateral cartilages must be narrowed. The intermediate osteotomy is useful in narrowing such a nose (Fig. 37-23). The intermediate osteotomy is carried out through the intercartilaginous incision above the upper lateral cartilages.

In the deviated nose, the lateral osteotomy follows the curvature of the nasofacial groove—that is, against the face of the maxilla—and with rotation of the osteotome, it curves upward to join the medial osteotomy. Provided the medial osteotomy has been done first as recommended, back fracture and bony spicules are rare.12,14 High osteotomies—that is, away from the maxillary face—are satisfactory for some cosmetic rhinoplasties, but with deviated external noses, low complete osteotomies are advised. These require the creation of a transverse fracture that joins the medial and lateral osteotomies at their cephalic ends.

Spreader Grafts

Once the ULCs have been freed from the septum, the degree of dorsal deviation can be determined. If there is a minor degree of dorsal deviation, the osteotomies may realign the nose to the midline, and the ULCs only need to be sutured to the septum. If there is a significant dorsal septal deviation, as seen in the C-shaped deformity, then an onlay graft can be placed on the concave side to camouflage the deformity. Another method to help efface the concavity of the septal deformity is by inserting a spreader graft. The spreader graft is carved from septal cartilage and is placed above the intact intranasal mucosa between the septum and ULC (Fig. 37-24). The graft will fill the concavity of the C-shaped deformity and preserve the cross-sectional area of the nasal valve. These grafts will also correct the depression seen from ULC collapse. If the dorsum is reduced more than 3 mm, the confluent width of the cartilaginous dorsum is dramatically compromised, and spreader grafts should be considered to avoid a narrowed dorsum and inverted V deformity.

Saddle Nose Deformity

Augmentation

The authors prefer using autogenous materials in the nose.15–22 Septal cartilage is preferred, but auricular and rib cartilage are also useful. If the bony pyramid needs augmentation, then autogenous iliac crest, calvarial bone, or rib can be used. Temporalis fascia and dermis are easily harvested and can be used to fill, contour, and soften certain nasal defects. Alloderm is processed from human dermis and can be used for augmentation in the same way as fascia or dermis. Homologous materials have been used with success,23 but in general are less desirable because of long-term unpredictability with resorption and buckling.24,25

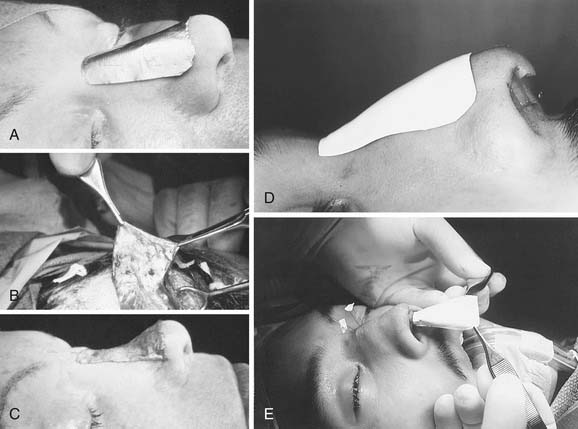

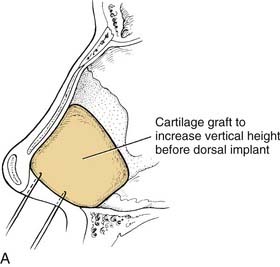

At this time Gore-Tex is our preferred alloplast for dorsal augmentation. The tolerance of Gore-Tex as an implant material has been well documented.11,26,27 In addition, minimal amounts of fibrous ingrowth lead to stability of the implant but do not restrict its removal when necessary. The reinforced sheets of 4 to 7 mm are much easier to sculpt for augmentation. With these implants and the sheeting, it is important to taper the edge to ensure smooth transition to the surrounding soft tissue. This can be done through sharp beveling with a scalpel or by crushing the margins with a hemostat or needle holder. For the saddle nose deformity in which extensive septal surgery and osteotomies are required, it is sometimes best to stage the procedure, with the implants being placed at a second operation. Extensive septal reconstruction may be essential in completely straightening the nose and in increasing the vertical height, thereby making the required size of the implant smaller (Fig. 37-25). In the saddle nose, the anterior valve is frequently circular rather than oval or piriform, and the septal reconstruction should be combined with intranasal Z-plasties to release the scar contractures and open the anterior valve areas.

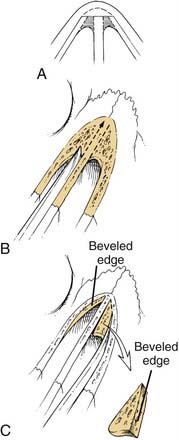

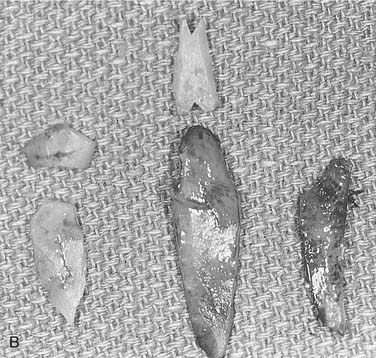

Figure 37-25. A, The septum and the saddle nose deformity. Straightened septal cartilage can be reinserted as a large columella strut to increase the vertical height of the nose and provide support for the dorsal implant. B, Cartilage implants taken from the nasal septum. C, Laminated cartilage implants to be sutured in position by the open approach. Irregularities may be smoothed out by a blanket of temporalis fascia or Gore-Tex sheeting. (See also Fig. 37-26.)

One of the difficulties of rhinoplasty, and especially of revision rhinoplasty, is ensuring a smooth contour over the nasal dorsum. This can be especially difficult in thin-skinned patients when implants are used. Where there are skin irregularities and scarring or cicatricial adhesions to the underlying framework, it is necessary to prevent recurrence once elevated. Sculpted laminated autogenous cartilage implants of any sort may leave irregular edges or an irregular surface. One way of softening these edges and other irregularities involves draping a piece of temporalis fascia over the entire bony and cartilaginous nasal framework. The temporalis fascia graft can be placed through either an intercartilaginous incision or an open rhinoplasty approach. The graft is secured in position with draw sutures, which are then tied over a soft plastic bolus at the level of the nasal frontal angle at each corner and with direct suturing inferiorly, laterally, and at the dorsum. Precise, direct suturing can be accomplished through the open rhinoplasty approach. Temporalis fascia has been shown not to resorb significantly in vivo,28 and donor site morbidity is minimal. This fascial graft technique is an important part of the surgical armamentarium, particularly for revision rhinoplasty, dorsal irregularities, scars, and overlying implants (Fig. 37-26). Gore-Tex 0.4-mm cardiovascular sheeting or Alloderm can be used in place of fascia with little risk of reaction or extrusions (see Figs. 37-26D and E).

Indications

The more severe saddle nose deformities have columellar retraction secondary to loss of quadrangular cartilage and a prolapsed dorsum. The cartilaginous and bony pyramid may be broadened and flattened, requiring multiple osteotomies. The dorsal implant should be carefully shaped with particular attention paid to preparing the recipient site and corresponding surface of the implant, so that the implant will fit snugly against roughened nasal bones. The undersurface of the implant should be concave to fit the curvature of the dorsum of the nose. A three-dimensional concept must be kept in mind when shaping the graft. The dorsal aspect of the graft should be nearly straight and extend the full length of the nose (Fig. 37-27). Grafts may be layered to increase the magnitude of augmentation. Bone grafts should be fixed to the nasal bones with a Kirschner wire or a miniplate. An external nasal splint should be applied for several days.

Dynamic Adjustable Rotational Tip Graft

Dynamic adjustable rotational tip (DART) grafts are extended dorsal spreader grafts that extend beyond the caudal septum the desired length of derotation.8 The DART is particularly useful in the overrotated nose when the inferior displacement of the entire tip complex is necessary and placement of a tip graft would exacerbate columellar show.8 The DART reestablishes the spring tension of the nasal tip. This helps establish a reliable nasal tip complex position and improves nasal valve collapse. Through an open approach, extended dorsal spreader grafts are typically sutured to a columellar strut and the medial crura of the lower lateral cartilage (Fig. 37-28). The extended spreader grafts can be slid along the anterior-posterior axis of the quadrangular cartilage. This allows the tip complex to be repositioned until the desired tip rotation and projection have been created. Once the desired tip position and tension have been created, the extended spreader grafts are sutured to the quadrangular cartilage. This extended graft helps derotate the tip and strengthen the dorsal septum and anterior septal angle.

The Noncaucasian Nose

Aesthetic surgery of the noncaucasian nose requires a detailed preoperative analysis to identify the structural deformities present. Once the deformities have been identified, the appropriate surgical modifications can be undertaken. The generalities that follow pertain mostly to the African-American nose, although the Asian and several other ethnic noses have similar characteristics. In general, the noncaucasian nose has thick skin, weak cartilages, a flat broad dorsum, and an underprojected poorly defined tip with a wide alar base (see Fig. 37-30A). The thick sebaceous inelastic skin limits the degree of nasal tip sculpting that can be appreciated. The adipose tissue in the tip can be removed, and postoperative subdermal injections of Kenalog can help decrease supratip edema and scar formation.

The external approach allows the surgeon excellent visualization and the ability to precisely place grafts. The transcolumellar incision in the noncaucasian nose should be placed slightly lower than in the caucasian nose, because the augmentation of the noncaucasian nose advances the columellar skin cephalically.11 If the incision is placed at the midcolumellar level, it may be advanced into the region of the infratip lobule.

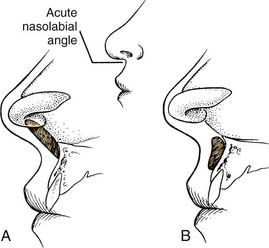

One of the most consistent findings in the noncaucasian nose is the acute nasolabial angle.25 The underdeveloped anterior nasal spine contributes to the acute nasolabial angle. Plumping grafts of solid or crushed cartilage or bone can be placed into the premaxillary area to correct the acute nasolabial angle. A columellar strut may also be used to fill this area and provide tip support.

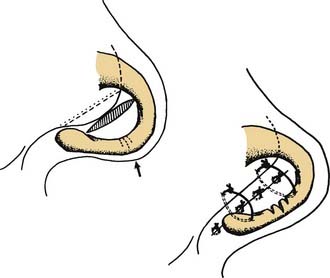

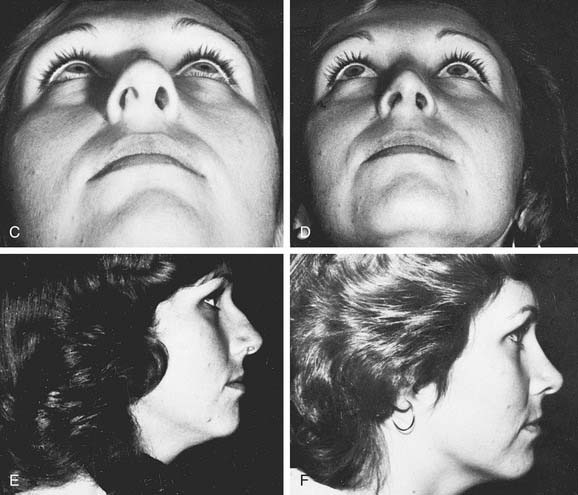

Nasal Base Sculpting

The planned approach and site of incisions used for reduction of the nasal base is dictated by the patient’s needs. The ala and nostrils can be reduced individually or in combination, depending on the need to reduce alar flare and nostril size. In general, the noncaucasian nose would need alar reduction with medial repositioning of the ala. An incision is made from the base of the sill and carried out 1 to 2 mm above the alar-facial crease (Fig. 37-29). The alar flap can be advanced medially, and a conservative amount of the ala can be excised. To avoid visible scaring, the cut edges should be carefully reapproximated. A 5-0 chromic suture should be used to reapproximate the alar rim, and one or two subcutaneous 5-0 Vicryl sutures should be placed to reapproximate the alar-facial junction incision. A few 6-0 nylon sutures are used to reapproximate the skin edges (Fig. 37-30).

Alar Soft Tissue Sculpturing

Reduction of the nasal base may be combined with surgery for the thick inferior border of the ala, which requires excision and thinning (Fig. 37-31). Further sculpturing may be required to arch the ala to correct alar hooding. In sculpturing or thinning the ala or nostril margin, one should make the excision slightly toward the nostril side. This not only makes the scar less visible but also creates a more natural roll to the border. The procedure is usually combined with a columella strut or other procedure to create greater columella “show” relative to the alar margin. Other techniques may be used to create greater columella prominence, such as the use of a composite auricular graft or skin and cartilage transposition flaps from the cephalic border of the lower lateral cartilages.

The Cleft-Lip Nose

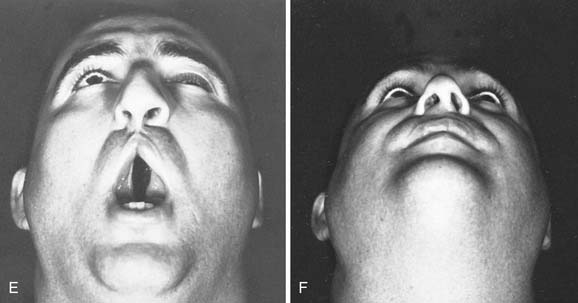

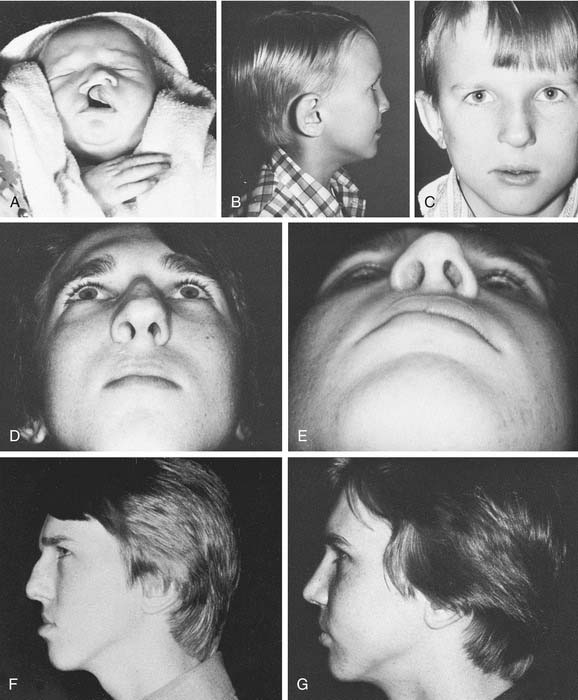

The cleft-lip nasal deformity requires special attention to the asymmetric and retrodisplaced lower lateral cartilage in the unilateral cleft and to the depressed tip with a relatively short columella in the bilateral cleft. Associated with the deformity is hypoplasia of the maxilla on the cleft side or bilaterally, with midfacial hypoplasia resulting from the lack of mesodermal penetration (Fig. 37-32).

Figure 37-32. Cleft-tip nasal deformities. A, Unilateral cleft-lip deformity. B, Bilateral cleft-lip deformity.

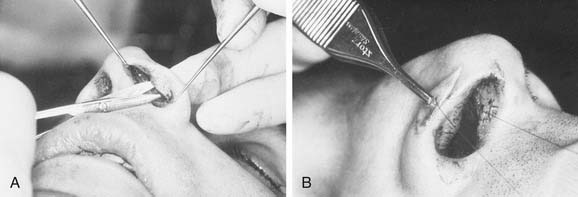

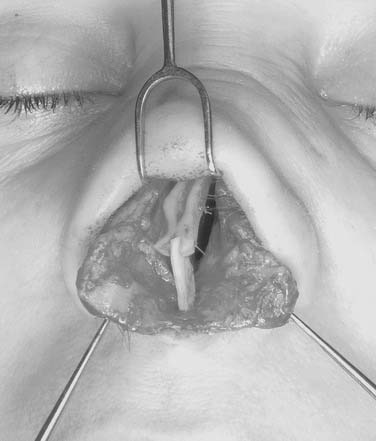

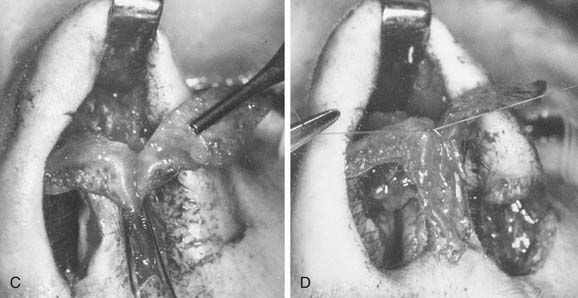

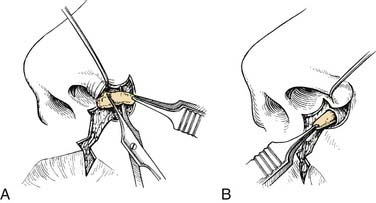

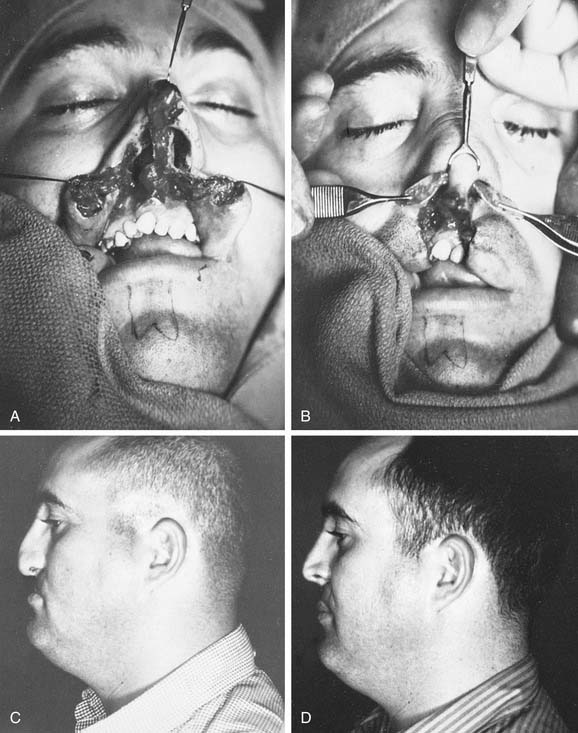

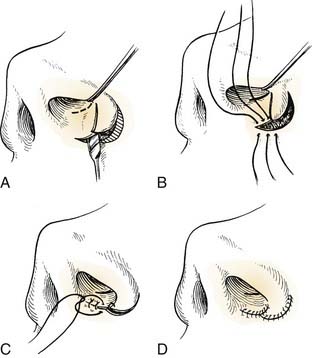

Although soft tissue repair can be readily accomplished at the time of initial lip repair or as revisional surgery, reconstruction will be inadequate if the asymmetry of cartilage and bone is not addressed. The authors most often use the external approach for both the unilateral and the bilateral cleft-lip nasal deformities.29,30 In the unilateral cleft-lip nasal deformity, the lateral crus of the lower lateral cartilage on the cleft side is dissected free of both surface and vestibular skin, and the cartilage is advanced medially to match the normal side (Fig. 37-33). The position is maintained with sutures to the opposite dome to project the tip on the cleft side, along with sutures through the vestibular skin, cartilage, and surface skin (see Fig. 37-33). These 5-0 nylon transalar sutures are tied over a thin flat plastic bolus on the surface skin side only. With the open rhinoplasty it is possible, under direct vision, to stabilize the involved lateral crus further by suturing it directly to the upper lateral cartilage or septum (Fig. 37-34). This is particularly important when the cleft side is caudally displaced, resulting in a hooding deformity of the columella.

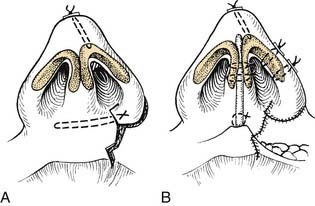

In the unilateral cleft-lip deformity, particular attention must be paid to the dislocation of the caudal septum toward the normal side and the posterior nasal septal spur on the cleft side. All septorhinoplasty techniques may be necessary in correcting the cleft-lip nasal deformity, and onlay grafts are frequently necessary beneath the alar base on the cleft side (Figs. 37-35 and 37-36). In the bilateral cleft-lip deformity, the cartilages can be precisely sculptured bilaterally and dissected free of both skin surfaces to allow medial recruitment and suturing to project the tip (Fig. 37-37).

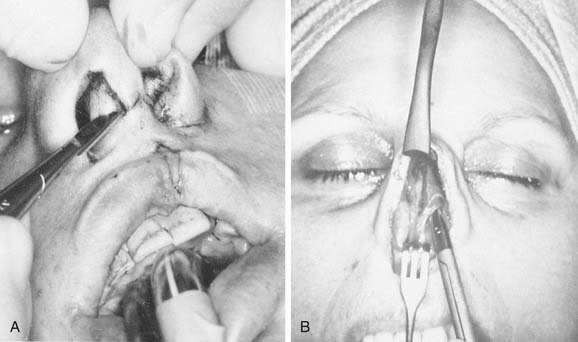

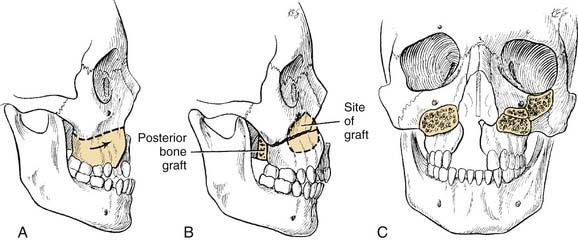

Grafts are combined with high Le Fort I osteotomies to advance the maxilla in severe deformities associated with both unilateral and bilateral cleft lips.31,32 Both maxillary and mandibular osteotomies may be required. There is some choice between suspension and intermaxillary wiring and miniplate fixation.31,33 Occlusion must be precise and is combined with interdental splinting and fixation. Bone grafts are placed between the advanced maxilla and the pterygoid plates, over the face of the maxilla, and about the piriform rim (Figs. 37-38 and 37-39).

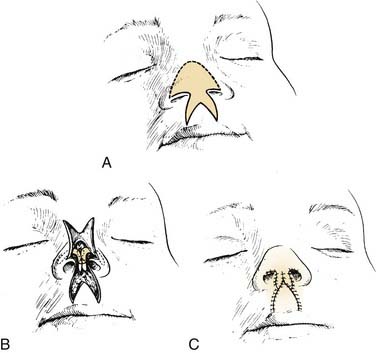

For the bilateral cleft-lip deformity, a variety of columella-lengthening procedures have been developed. Selection depends on the severity of the deformity and what previous surgery has been performed. The most commonly used procedures for lengthening the skin of the columella are the forked flap of Millard (Fig. 37-40)34 and the advancement flap from the floor of the nose of Brauer and Cronin (Fig. 37-41).35 Both of these procedures provide augmentation of the columella and, when combined with techniques to project the domes of the lower lateral cartilages, result in a marked improvement in the patient’s appearance.

When stenosis of the nasal airway is present, the preceding techniques can be used for managing the lower lateral cartilage and septal and alar deformities, but the alar attachment must be displaced laterally to open the airway. The floor is widened with a V to Y advancement flap. The ala is then advanced laterally by excising a crescent of skin just lateral to the site of alar attachment (Fig. 37-42).

Broadbent TR, Woolf RM. Anatomy of a rhinoplasty-saw technique. Ann Plast Surg. 1984;13:67.

Broadbent TR, Woolf RM. Basic anatomy: clinical application in rhinoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1984;13:76.

Converse JM. Reconstructive Plastic Surgery. Vols II and III. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1964.

Denecke HJ, Meyer R. Plastic Surgery of the Head and Neck, Corrective and Reconstructive Rhinoplasty. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1967.

Diamond H. Rhinoplasty techniques. Surg Clin North Am. 1971;51:317.

Herber SC, Lehman JA. Orthognathic surgery in the cleft lip and palate patient. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:755.

Johnson CM, Toriumi DM. Open Structure Rhinoplasty. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990.

Meyer R. Correction of Rhinoplasty Complications, Transactions of the Vth International Congress on Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Melbourne: Butterworth; 1971.

Meyer R. Secondary and Functional Rhinoplasty, The Difficult Nose. Orlando, Fla: Grune & Stratton; 1988.

Rees TD, Guy CL, Converse JM. Repair of the cleft lip nose: addendum to the synchronous technique with full thickness skin grafting of the nasal vestibule. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;37:47.

Rees TD, Wood-Smith D. Rhinoplasty. In: Cosmetic Facial Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1973.

Schuller DE, Bardach J, Krause CJ. Irradiated homologous costal cartilage for facial contour restoration. Arch Otolaryngol. 1977;103:12.

Tardy ME, Brown RT. Surgical Anatomy of the Nose. New York: Raven Press; 1990.

Tardy ME. Rhinoplasty The Art and Science. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997.

Toriumi DM, Sykes JM, Johnson CM. Open structure rhinoplasty for management of the non-Caucasian nose. Oper Techn Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;4:225.

Wright WK. Surgery of the bony and cartilaginous dorsum. Otolaryngol Clinic North Am. 1975;8:575.

1. Converse JM. Corrective surgery of nasal deviations. Arch Otolaryngol. 1950;52:671.

2. Farrior RT. Management of the late sequelae of nasal fractures. In: Mathog RH, editor. Maxillofacial Trauma. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1984.

3. Becker OJ. Problems of septum in rhinoplastic surgery. Arch Otolaryngol. 1951;53:622.

4. Daniel RK. Rhinoplasty: a simplified, three stitch open tip suture technique, part 1: primary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:1491.

5. Goodman WS. Recent advances in external rhinoplasty. J Otolaryngol. 1981;10:433.

6. Rees TD, Krupp S, Wood-Smith D. Secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1970;46:332.

7. Strezlow VV. External septorhinoplasty approach to septal surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 1984;2:65.

8. Dyer WKII, Yune ME. Structural grafting in rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 1997;13:269.

9. Farrior EH, Farrior RT. The septocolumella complex. In: Stucker FJ, editor. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Head and Neck: Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium. Philadelphia: Mosby, 1991.

10. Baker SR. Suture contouring of the nasal tip. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2000;2:34.

11. Waldman RS. Gore-Tex for augmentation of the nasal dorsum: preliminary report. Ann Plast Surg. 1991;26:520.

12. Farrior RT. Corrective and reconstructive surgery of the external nose. In: Naumann HH, editor. Head and Neck Surgery. Stuttgart: Thieme, 1980.

13. Farrior RT. The osteotomy in rhinoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1978;88:1449.

14. Wright WK. General principles of lateral osteotomy and hump removal. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1961;65:854.

15. Bull TR, MacKay IS. Augmentation rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg. 1984;1:125.

16. Dingman RO. The use of iliac bone in the repair of facial and cranial defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;43:117.

17. Dingman RO, Walter C. Use of composite ear grafts in correction of the short nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;43:117.

18. Farrior RT. Implant materials in restoration of facial contour. Laryngoscope. 1966;76:934.

19. Farrior RT. Synthetics in head and neck surgery. Arch Otolaryngol. 1966;84:82.

20. Guerrerosantos J. Temporoparietal free fascia grafts in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;11:491.

21. Sheen JH. Achieving more nasal tip projection by the use of a small autogenous bone or cartilage graft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;56:35.

22. Walter C, Brunt PB. Tricalciumphosphate as an implant material: preliminary report. Br J Plast Surg. 1982;35:510.

23. Lefkovits G. Irradiated homologous costal cartilage for augmentation rhinoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;25:317.

24. Kridel RW, Konoir RJ. Irradiated cartilage grafts in the nose, a preliminary report. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;119:24.

25. Stucker FJJr. Non-Caucasian rhinoplasty and adjunctive reduction cheiloplasty. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1987;20:877.

26. Neel HB. Implants of Gore-Tex. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:428.

27. Stoll W. The use of polytetrafluoroethylene for particular augmentation of the nasal dorsum. Esthet Plast Surg. 1991;15:233.

28. Miller TA. Temporalis fascia grafts for facial and nasal augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81:524.

29. Farrior RT. The problem of the unilateral cleft-lip nose. Laryngoscope. 1962;72:289.

30. Farrior RT. The cleft-lip nose (septorhinoplasty and combined lip repair). In: Sisson GA, Tardy EM, editors. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Face and Neck: Proceedings of the Second International Symposium, Vol 1. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1977.

31. Farrior RT. The cleft lip nose: an update. Facial Plast Surg. 1993;9:241.

32. Obwegeser HL. Surgical correction of small or retroplaced maxillae, “the dish face deformity.”. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;43:351.

33. Farrior RT, Pennington JH, Stucker FJ, editors. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery of the Head and Neck: Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium. Philadelphia: Mosby, 1991.

34. Millard DR. Columella lengthening by a forked flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1958;22:454.

35. Cronin TD. Lengthening columella by use of skin from nasal floor and alae. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1958;21:417.