Chapter 25 Special Problems of Otosclerosis Surgery

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Before embarking on the nuances of primary and revision stapedectomy, first let us summarize a more recent finding with regard to pregnancy and its effect on otosclerosis. Traditional teaching has assumed that pregnancy would exacerbate otosclerosis. Our evaluation of incidence and progression of otosclerosis in women with children versus childless women has conclusively shown no impact of the pregnancy on further hearing loss in otosclerosis.1

This chapter reviews the technique of stapedectomy and the principles that prevent misadventures and discusses solutions to unusual problems. In addition, revision techniques for failed stapedectomy are described in detail. Finally, experience is presented in specific areas, such as far advanced otosclerosis with little or no testable hearing, and stapedectomy in children, in elderly patients, in patients with small air-bone gaps, and in fighter pilots. Stapedectomy in the presence of chronic otitis media, the need for promontory drilling, and findings in the other ear in patients with otosclerosis also are summarized.2–4

INTRAOPERATIVE AUDIOMETRY

Any portable audiometer can be used. One of the earphones is removed from the headset and inserted into a sterile plastic sleeve, which is available as a disposable orthopedic drill sleeve. The surgeon holds the sterile earphone to the patient’s ear (Fig. 25-1). Testing begins with the presentation of a tone that is easily heard by the patient.

Testing by an audiometer in the operating room offers several advantages. First, the surgeon and the patient have instant and accurate feedback on the success of the operation. Second, the improvement of hearing defines the end point of surgery. Third, in revision cases, the surgeon can explore the footplate area without opening the oval window by repositioning the prosthesis in various locations in the oval window. Finally, in difficult cases, different techniques can be attempted to determine the best prosthesis and best placement for optimal hearing.5

ROUTINE STAPEDECTOMY

The speculum holder, which is always used, is positioned so that each portion of the tympanomeatal flap incision is visible as it is made. The flap should be elevated carefully to prevent damage to the skin and tympanic membrane. As the middle ear is entered, an absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) pledget soaked in the previously mixed anesthetic solution is placed into the middle ear to anesthetize the middle ear mucosa. As the drum is pushed back, the manubrium of the malleus and incus can be seen and palpated. Any fixation should not preclude completion of the operation, but should be noted so that the patient can be advised later if the hearing result is suboptimal.6

After the incudostapedial joint is severed and the tendon is cut, the superstructure is fractured toward the promontory and removed to expose the footplate. The control hole can now be extended across the footplate, and the footplate posterior to the hole is removed. A stapedotomy or partial stapedectomy is done. We have found no significant difference in outcome when comparing stapedotomy, partial stapedectomy, or total stapedectomy except for the lower rate of overclosure in stapedotomies.7 A vein from the forearm, previously harvested, pressed, and prepared, is immediately placed across the oval window with the adventitial side down to seal and protect the vestibule.

Until more recently, the Robinson stainless steel piston prosthesis was used in all cases. This prosthesis comes with either a standard or large well, 0.4 or 0.6 mm stem width, and in various lengths. We have found that a prosthesis with a large well, narrow stem, and length of 4 mm is suitable in 99% of cases, eliminating the need to measure. Instead of the stainless steel prosthesis, we now use the titanium bucket handle prosthesis. With potential future advances in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology in mind, we made the change from stainless steel prosthesis to the titanium prosthesis to optimize MRI compatibility. Results obtained using the titanium prosthesis are equal to the results obtained using the stainless steel prosthesis. In addition to increased MRI compatibility, an advantage offered by use of the titanium prosthesis is that there is no reflection of light from the titanium prosthesis.8 The absence of a reflection enables the surgeon to visualize the placement of the prosthesis better.

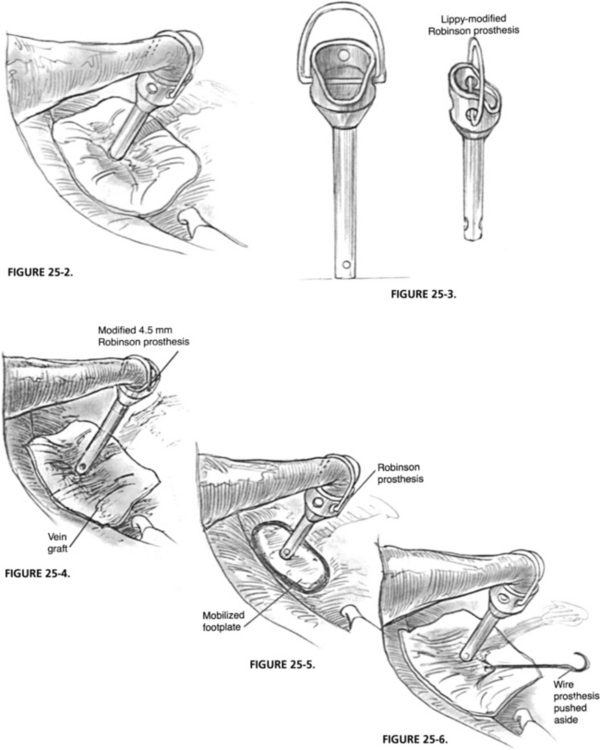

The prosthesis is placed by use of a two-handed technique. One hand lifts the incus with an incus hook, while the other gently directs the prosthesis with a strut guide. A controlled study evaluating hearing results with various prosthesis widths revealed similar hearing results in 0.4 and 0.6 mm prostheses. The narrow 0.4 mm stem prosthesis is used because the 0.6 mm prosthesis occasionally can be too wide for a narrow oval window niche.9 Because this prosthesis centers itself in the oval window opening, middle ear packing is not used. The patient’s hearing can be tested immediately after the tympanic membrane is replaced. If the wire keeper does not easily swing over the lenticular process, its use is unnecessary. Forcing it may displace the prosthesis from the center of the oval window (Fig. 25-2).

FIGURE 25-2 Routine stapedectomy.

FIGURE 25-3. Lippy modified Robinson prosthesis.

FIGURE 25-4. Modified 4.5 mm Robinson prosthesis in place on vein graft covering oval window.

FIGURE 25-5. Robinson prosthesis in place on mobilized footplate.

FIGURE 25-6. Revision stapedectomy wire prosthesis is pushed aside.

INTRAOPERATIVE PROBLEMS

Atrophic Tympanic Membrane

An atrophic tympanic membrane may signal a poor blood supply to the incus. An atrophic membrane has been observed on exploration in revision stapedectomy with erosion of the lenticular process being a common finding.10 As in treatment of a perforation, the intact tympanic membrane is reinforced from the underside of the tympanic membrane with tissue. This may be vein, fascia, or, in more severe cases, perichondrium or cartilage. This procedure should thicken the tympanic membrane and protect the incus by providing a better blood supply.

Fixed Malleus

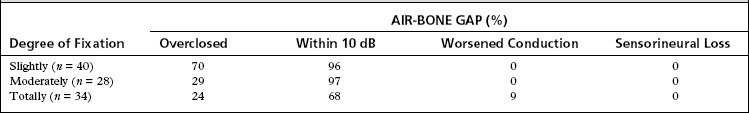

The malleus must always be routinely palpated with the same instrument under the surgeon’s direct vision from the underside of the tympanic membrane. The malleus may be slightly fixed, moderately fixed, or totally fixed. If fixation is slight or moderate, the final result of stapedectomy would be as if the malleus had not been fixed at all. The success rate would be the same (96% to 97%), but the overclosure rate would be substantially reduced.11 Partial malleus fixation should be ignored. When the malleus (and probably the incus) is totally fixed, a stapedectomy should be completed, if the patient also has a fixed footplate.

Most of the footplate should be removed to create a large enough oval window opening for a second future procedure (malleus or tympanic membrane to oval window technique). Of totally fixed malleus cases, 68% are successful to within 10 dB, and the air-bone gap is closed to within 10 to 20 dB in an additional 15%. Cases with an air-bone gap of 25 dB or more should be considered for a second-stage procedure. Applying this simple solution over the past 20 years, we have had good hearing results, and no patient with otosclerosis and a fixed malleus has had a further sensorineural hearing loss (Table 25-1).

Fused Incudostapedial Joint

If the joint cannot be separated with a joint knife, the laser can be used instead.

Partial Absence of the Incus

When a partial absence of the long process of the incus is found in a patient with otosclerosis, a stapedectomy is still done. Incus erosion is the second most common finding in revision stapes surgery; a crimped wire prosthesis causes erosion twice as often as the Robinson prosthesis. In place of the standard prosthesis, the Lippy modified Robinson prosthesis is used. The fenestra should be larger than usual because the prosthesis does not self-center.11,12 The technique of prosthesis placement is important to success (see Video 25-1).

The lower stem end of the prosthesis is placed on the vein graft, the upper end with the open well toward the eroded incus. The prosthesis is guided onto the remaining incus from the direction of the promontory. A significant foreshortening of the eroded incus or overhang of the facial nerve necessitates use of an offset Lippy modified prosthesis, yielding more length to avoid the facial nerve.10 In long-term follow-up using the Lippy modified prosthesis in nonrevision cases, initial success (<10 dB air-bone gap) was 90% with long-term hearing (<10 dB air-bone gap) maintained in 86% of patients.10 If the lenticular process comes to a pointed rather than a blunted end, the laser is used to square the end. The laser can also be used to thin or sculpture an incus that is too thick to accept the Lippy modified prosthesis (Figs. 25-3 and 25-4).

Dehiscent Facial Nerve

In otosclerosis surgery, the facial nerve rarely interferes with a stapedectomy except in a congenitally deformed middle ear, or when the facial nerve canal is completely dehiscent. In cases in which more than 50% of the footplate was covered by the facial nerve, the overall success of stapedectomy was similar to that of cases in which the footplate was not covered.13 If any part of the footplate is visible, a stapedectomy usually can be accomplished. A hole should be made first in the visible part of the footplate. Often, a large portion of the footplate can be removed from underneath the dehiscent nerve by retraction of the facial nerve with the shaft of the same instrument used to extract the footplate. If the footplate cannot be removed, the technique is to shatter the footplate with a pointed pick—even blindly, if necessary. After a vein graft is placed across the open oval window, the prosthesis is inserted by compressing the facial nerve with the prosthesis.

Obliterative Otosclerosis

In the 1960s, 30% of the footplates were drilled; in the 1970s, 9%; in the 1980s, 4%; and in the 1990s, 6%. Fifty-five percent of the cases overclosed, 80% were successful, and 0.2% were worse. Although the results of drill-out cases are acceptable, they are not as good as routine cases. Preoperatively, the surgeon should be more suspicious of a possible drill-out in an obliterated footplate if the patient presents with a more than 30 dB air-bone gap or has had otosclerosis for many years. Suspicion should also be high in patients whose hearing loss begins early in life.14

Narrow Oval Window Niche and Promontory Drilling

We evaluated a group of patients with otosclerosis who underwent promontory drilling to carry out stapedectomy.3 There was no deterioration in bone conduction hearing or in speech discrimination ability in this group. These patients did as well as a control group of patients with stapedectomies in whom the promontory was not drilled.

Floating Footplate

The footplate can move when the surgeon is drilling a hole in the fixed footplate, fracturing the stapes superstructure, or extracting the fixed footplate. The most common cause of a floating footplate from the 1960s to the early 1980s was drilling on a solid footplate. From the early 1980s through the 1990s, the most common cause was fracturing the superstructure.15

When the footplate is mobilized, regardless of whether it is solid (white) or diffuse (blue), a vein graft is placed on top of the mobilized footplate, followed by placement of a Robinson prosthesis attached to the lenticular process (Fig. 25-5).16 This conservative method gives excellent long-term results. If the mobilized footplate is mostly blue with diffuse otosclerosis, the hearing success rate is 97%. Long-term hearing results at 3 years remained the same for the mobilized blue footplate with no refixation. If the footplate is thick, white, or biscuit shaped, the hearing success rate is 52%. If the thick, white footplate later refixes, it can be revised during a revised stapedectomy. Refixation occurred in 30% of mobilized thick, white, obliterative footplates. If we add the results of the unsuccessful cases that required revisions to the initially successful cases, the final success rate is 76%. If the footplate again moves during the revision procedure, no future surgery should be planned.

Following this protocol, none of 147 cases of a floating footplate in a series of 8000 cases developed a further sensorineural loss (Table 25-2). In recent years, the laser has been used in the moderately thick footplate, preferably before it mobilizes.

| Hearing | FOOTPLATE | |

|---|---|---|

| Thick White (n = 56) (%) | Thin Blue-Mixed (n = 92) (%) | |

| Successful | 52 | 95 |

| Conduction worse | 7 | 2 |

| Sensorineural loss worse | 0 | 0 |

| Successful after revision | 76 | — |

REVISION STAPEDECTOMY

Our experience is based on more than 1800 cases.19–21 Cases are divided into two major categories: sensorineural hearing loss and conductive hearing loss. These cases are divided further by the type of prosthesis and oval window covering used in the primary surgery.

Elderly patients may undergo revision stapedectomy. We compared a group of patients older than 65 years with a group younger than 65, and the success rate was very similar. There was no increase in side effects secondary to surgery in the patients older than 65.22

Sensorineural Hearing Loss

In patients with delayed sensorineural hearing loss after stapedectomy with a piston and an oval window tissue seal, revision is indicated only for a history of trauma or dizziness. Before this directive, in 27 cases, 79% had negative surgical findings with no evidence of a surgical problem or oval window fistula. Only one case had a fistula.17

In cases with a delayed or immediate sensorineural hearing loss and without an oval window tissue seal, the findings at revision surgery are more dramatic. Most cases had a wire prosthesis with either Gelfoam or a blood clot as an oval window seal; 50% of the cases had oval window fistulas. These cases were revised with an oval window tissue seal and a Robinson prosthesis. Hearing improved in a few cases, and dizziness improved in 75%. The next most common findings were cases with negative surgical findings and prostheses that were too long when placed. Table 25-3 illustrates findings in the cases with sensorineural hearing loss by comparing cases with and without a tissue graft.

TABLE 25-3 Surgical Findings in Revision of Sensorineural Cases

| Surgical Findings | Tissue Seal (n = 29) (%) | No Tissue (n = 42) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Negative findings | 79 | 24 |

| Fistula | 4 | 50 |

| Long prosthesis | 0 | 21 |

| Tissue reaction | 10 | 5 |

| Lateral vein | 7 | 0 |

Conductive Hearing Loss

The deciding factor for revision of conductive hearing loss is the hearing history after the primary procedure.17,18 The most appropriate surgical candidates have hearing improvement postoperatively and then development of another conductive hearing loss. Patients with the same or worse hearing postoperatively have a low success rate for revision surgery (Table 25-4).

| Air-Bone Gap | Successful Hearing (%) |

|---|---|

| Delayed conduction | 70 |

| No change in hearing | 35 |

| Increased conduction | 25 |

The operative experience of the previous surgeon is another factor. The greater the surgical experience, the less likely a reversible problem would be solved. Patients whose first surgeon was an experienced stapes surgeon and whose hearing did not improve are usually poor candidates for revision.19,20

The type of prosthesis used and whether an oval window tissue graft was used are also important. Conductive hearing loss with a Robinson prosthesis and vein is most frequently due to incus erosion, prosthesis malfunction, or negative findings.14,21 In cases of eroded incus, many tympanic membranes were atrophic. In these cases, the tympanic membrane is reinforced with fascia or vein. To decrease prosthesis malfunction, a large well with a narrow shaft is used in all stapedectomies, allowing the prosthesis more freedom of movement to center in the oval window.10 Incus erosion is common with a wire prosthesis and can be revised with good hearing results. Partial stapedectomy, in which the crus is mobilized into an opened covered oval window, is a procedure that is usually revised with a good result.

Surgical Technique

The surgical technique includes removing the previously placed prosthesis without disturbing the oval window seal, and placing a vein graft and a Robinson prosthesis. In cases with a wire prosthesis in which the patient experiences dizziness on manipulation, the end of the wire that is attached to the incus is detached and pushed aside, leaving the distal end of the wire in the oval window seal (Fig. 25-6). A vein graft is placed over the oval window area with a slit cut in the graft to accommodate the wire. A Robinson prosthesis is placed (see Video 25-1).

Surgical Findings

Incus Erosion

Incus erosion is the most common finding with wire prostheses. The pressure of the wire around the long process of the incus causes necrosis and erosion. If the only problem is a loose wire, the prosthesis can be crimped again. With prostheses that attach to the lenticular process of the incus, such as the Robinson, incus erosion most often results from a previous infection, manifested by a healed perforation or an atrophic tympanic membrane and incus. For wires and pistons, the success rate of revision with the Lippy modified Robinson prosthesis is 80%.18

Negative Findings

The so-called negative surgical finding category refers to the situation that occurs when no problem can be recognized. In cases with an oval window tissue seal and a piston prosthesis, a revision stapedectomy did not improve hearing. Hearing improved in 60% of cases, however, in which a wire prosthesis without a tissue seal was replaced by a Robinson prosthesis on a vein (Table 25-5). The reason for this disparity seems to be the efficiency of the Robinson prostheses. The heavier and more rigid piston prosthesis more closely resembles the stapes mass than does the wire prosthesis and is more efficient. With the use of laser, there are fewer cases that we call “negative findings” patients.

| Prosthesis | HEARING RESULTS (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Successful Hearing | Worse Hearing | |

| Wire–no tissue | 60 | 0 |

| Robinson-tissue | 0 | 9 |

Malleus Fixation

Malleus and incus fixations are discussed in the section on intraoperative problems. Malleus fixation may have been present but ignored at the initial surgery, or it may have progressed in the interim. Totally fixed cases can be revised with a footplate-to-drum prosthesis or a malleus-to-footplate prosthesis when an oval window tissue seal is present. Total ossiculoplasty with footplate removal may be performed at the same setting if the middle ear is healthy. The tissue seal preferably is vein or areolar fascia.23

Recommendations

In cases of revision stapedectomy, the following measures are recommended:

FAR ADVANCED OTOSCLEROSIS

Most important is the ability to hear, not just feel, the 512 Hz tuning fork on the upper teeth. This practical test gives 10 dB more gain than when the tuning fork is placed on the mastoid. Edentulous patients are tested on their dentures or on their gums if they have no dentures.24 In some patients, this test is the only one to yield measurable hearing evidence of far advanced otosclerosis. Patients with some of these findings should be considered for a stapedectomy.

Surgical Technique

In far advanced otosclerosis, the surgical techniques are the same as in routine stapedectomy, but the surgical findings are different. Fifty percent of the patients have obliterative otosclerosis; the surgeon must be prepared to drill the footplate extensively, as recommended previously.25

STAPEDECTOMY FOR SMALL AIR-BONE GAPS

Although most otologic surgeons advocate at least a 20 dB pure tone average air-bone gap as an indication for stapedectomy, a review by the senior author (W.H.L.)27 reveals that even smaller air-bone gaps may be corrected. Among 136 cases, overclosure was achieved in more than 80% of the patients with mean overclosure of 8.1 dB.27 These patients had a 10 dB or slightly less preoperative air-bone gap with an average 16.7 dB improvement postoperatively. Five-year follow-up revealed that almost all patients maintained their initial gains.

STAPEDECTOMY IN CHILDREN

Approach and management of children with otosclerosis differ from those of adults with otosclerosis. In our review of 47 children 7 to 17 years old, footplate pathology was greater in children necessitating drill-outs in 27% of cases for obliterative otosclerosis.28 In cases where inner ear malformations were suspected, they were ruled out with computed tomography (CT), and no such cases were identified in this study. Some older children can be operated with a local anesthetic. There is a greater than 90% chance of closing the air-bone gap to within 10 dB. In 5-year follow-up, the mean pure tone average deteriorated an average of 8.1 dB. Overclosure is not as great as in adult patients.

STAPEDECTOMY IN ELDERLY PATIENTS

Although otosclerosis usually manifests in patients younger than 40 years, some patients delay surgery until they are older than 70 years. In a review of 154 patients ranging in age from 70 to 92 years, 91% closed the air-bone gap to within 10 dB.29 Results were stable at 5 years with 2.5 dB deterioration at 5 years. There was no increase in complications in the elderly compared with a comparison younger group, with transient dizziness occurring in less than 2% of the patients postoperatively.

STAPEDECTOMY IN PILOTS

High-performance pilots with otosclerosis are a special group warranting attention. Six fighter pilots underwent stapedectomy, with three having bilateral stapedectomy.30 All the pilots returned to their active flight duties with no vestibular symptoms. Full flight status may be resumed after an altitude pressure test and a waiting period of 3 months.

STAPEDECTOMY IN PATIENTS WITH CHRONIC OTITIS MEDIA

The need for stapedectomy in patients with chronic otitis media is rare.2 Before performing stapedectomy, the middle ear should be free of fluid, and the tympanic membrane should be intact. When these two conditions have been met, stapedectomy may be performed.

The stapes fixation in these cases is due to tympanosclerosis secondary to chronic otitis media. In our review,2 these patients had significant improvement in their hearing, although the air-bone gap closure was less than that achieved in patients with otosclerosis. This difference is probably due to some residual stiffness and thickening of the tympanic membrane.

FINDINGS IN BILATERAL STAPEDECTOMIES

Because of the high percentage of patients developing bilateral otosclerosis, information on possible abnormal findings in the contralateral ear would be valuable. We reviewed 1800 patients and found that bilateral middle ear abnormalities occurred in 25% of the patients. The most common abnormality noted was obliterative otosclerosis (40% of the patients) requiring drill-out of the footplate. The second most common finding was overhanging facial nerve.4

1. Lippy W.H., Berenholz L.P., Schuring A.G., Burkey J.M. Does pregnancy affect otosclerosis? Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1833-1836.

2. Berenholz L.P., Lippy W.H., Burkey J.M., et al. Stapedectomy following tympanoplasty. Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:444-446.

3. Lippy W.H., Berenholz L.P., Schuring A.G., et al. Promontory drilling in stapedectomy. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:439-441.

4. Daniels R.L., Krieger L.W., Lippy W.H. The other ear: Findings and results in 1,800 bilateral stapedectomies. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:603-607.

5. Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G., Rizer F.M. Intraoperative audiometry. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:214-216.

6. Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G., Ziv M. Stapedectomy for otosclerosis with malleus fixation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1978;104:338-389.

7. Rizer F.M., Lippy W.H. Evolution of techniques from the total stapedectomy to the small fenestra stapedectomy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1993;26:443-451.

8. Lippy W.H., Burkey J.M., Schuring A.G., Berenholz L.P. Comparison of titanium and Robinson stainless steel stapes piston prostheses. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:874-877.

9. Fucci M.J., Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G., Rizer F.M. Prosthesis size in stapedectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118:1-5.

10. Krieger L.W., Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G., Rizer F.M. Revision stapedectomy for incus erosion: Long-term hearing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:370-373.

11. Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G. Solving ossicular problems in stapedectomy. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1147-1150.

12. Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G. Prosthesis for the problem incus in stapedectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1974;100:237-239.

13. Neff B.A., Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G., Rizer F.M. Stapedectomy in patients with a prolapsed facial nerve. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:597-603.

14. Lippy W.H., Berenholz L.P., Burkey J.M. Otosclerosis in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1307-1309.

15. Lippy W.H., Fucci M.J., Schuring A.G., Rizer F.M. Prosthesis on a mobilized stapes footplate. Am J Otol. 1996;17:713-716.

16. Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G. Treatment of the inadvertently mobilized footplate. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1973;98:80-81.

17. Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G. Stapedectomy revision following sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:580-582.

18. Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G. Stapedectomy revision of the wire-Gelfoam prosthesis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1983;91:9-13.

19. Lippy W.H., Schuring A.G., Ziv M. Stapedectomy revision. Am J Otol. 1980;2:15-21.

20. Lippy W.H. Revision stapedectomy. In: Johnson Jonas T., editor. AAO-HNS Instructional Courses. St Louis: Mosby–Year Book, 1994.

21. Lippy W.H., Battista R.A., Berenholz L.P., et al. Twenty-year review of revision stapedectomy. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24:560-566.

22. Lippy W.H., Wingate J., Burkey J.M., et al. Stapedectomy revision in elderly patients. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1100-1103.

23. Berenholz L., Lippy W.H. Total ossiculoplasty with footplate removal. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:120-124.

24. Lippy W.H., Rotolo A.L., Berger K.W. Bone conduction measurement: Mastoid versus upper central incisor. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1966;70:1084-1088.

25. Lippy W.H., Battista R.A., Schuring A.G., Rizer F.M. Far-advanced otosclerosis. Am J Otol. 1994;15(5 Pt 2):225-228.

26. Lippy W.H., Burkey J.M., Schuring A.G., Rizer F.M. Word recognition score changes following stapedectomy for far-advanced otosclerosis. Am J Otol. 1998;19:56-58.

27. Lippy W.H., Burkey J.M., Schuring A.G., Rizer F.M. Stapedectomy in patients with small air-bone gaps. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:919-922.

28. Lippy W.H., Burkey J.M., Schuring A.G., Rizer F.M. Stapedectomy in children: Short- and long-term results. Laryngoscope. 1998;108:569-572.

29. Lippy W.H., Burkey J.M., Fucci M.J., et al. Stapedectomy in the elderly. Am J Otol. 1996;17:831-834.

30. Katzav J., Lippy W.H., Shaniss A., Davidson B.Z. Stapedectomy in combat pilots. Am J Otol. 1996;17:847-849.