Chapter 62 Special considerations in skin of color

Taylor SC, Cook-Bolden F: Defining skin of color, Cutis 69:435–437, 2002.

U.S. Census Bureau: 2008 national population projections: tables and charts. Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/tablesandcharts.html. Accessed March 13, 2010.

Jablonski NG, Chaplin G: The evolution of human skin coloration, J Hum Evol 39:57–106, 2000.

Pappert AS, Scher RK, Cohen JL: Longitudinal pigmented nail bands, Dermatol Clin 9:703–716, 1991.

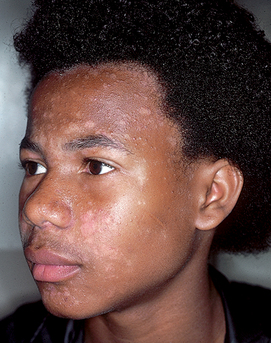

Figure 62-2. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in a patient with lupus erythematosus.

(Courtesy of James E. Fitzpatrick, MD.)

Nordlund JJ: The epidemiology and genetics of vitiligo, Clin Dermatol 15:875–878, 1997.

Figure 62-6. Annular lichen planus, demonstrating central postinflammatory hypopigmentation.

(Courtesy of James E. Fitzpatrick, MD.)

McLaurin CI: Unusual patterns of common dermatoses in blacks, Cutis 32:352–355, 358-360, 1983.

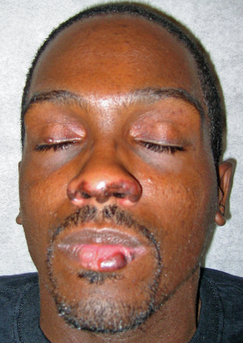

Figure 62-7. Multiple sarcoidal granulomas along the right eyelid, nasal margin, and lower lip in a patient with sarcoidosis.

(Courtesy of Whitney A. High, MD)

High WA: A woman with “keloids” on the nose and restrictive pulmonary disease, Medscape Dermatol Clin, September 7, 2004. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/488343. Accessed March 13, 2010.

Kelly AP: Update on the management of keloids, Semin Cutan Med Surg 28:71–76, 2009.

Kelly AP: Pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae, Dermatol Clin 21:645–653, 2003.

High WA, Hoang MP: Lipedematous alopecia, J Am Acad Dermatol 53:S157–S161, 2005.

McMichael AJ: Ethnic hair update: past and present, J Am Acad Dermatol 48:S127–S133, 2003.

Key Points: Skin of Color

Figure 62-10. Coccidioidomycosis. Disseminated coccidioidomycosis in a young black soldier.

(Courtesy of the Fitzsimons Army Medical Center teaching files.)

Pappagianis D: Epidemiology of coccidioidomycosis, Curr Top Med Mycol 2:199–238, 1988.

Gloster HM, Neal K: Skin cancer in skin of color, J Am Acad Dermatol 55:741–760, 2006.

Hinds GA, Herald P: Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in skin of color, J Am Acad Dermatol 60:359–375, 2009.

Table 62-1. Dermatologic Conditions More Common in Skin of Color