6 Special circumstances and considerations

6.1 How can families come to terms with the illness?

There are other aspects of the illness that families have to grapple with including the loss of hopes and dreams for the patient and for themselves and others in the family. Taking a realistic look at the illness and how much it will affect everyone’s lives is hard as there is a lot of uncertainty, particularly in the early years. Some will tend to go down a path of denial, and this is an aspect of thinking that most families go through at some point. They may either ignore what has happened or just hope that it will not happen again. Alternatively, they may move to the other extreme and assume that normal life is now entirely over. Keeping a realistic view of the future is important, and revising it as events unfold is part of that.

6.2 What is the best way to present information to parents about the cause of bipolar disorder?

Try to put this into perspective for the parents. There are risks for all of us that our children may develop manic depression (about 1%). If a parent suffers from manic depression then there is about a 10% risk of any child having a bipolar illness. The risk of depression in the general population is about 5% but nearer 25% for the children of bipolars. Depression and bipolar illness are also very variable illnesses in their severity. These are substantial figures but on average if a manic patient had four children only one is likely to have a serious affective disorder, and there are of course many other possible illnesses for which they may be at risk (see Fig. 2.2).

6.3 Do manic depressives have cognitive or intellectual deficits?

It is easy to recognise the intellectual impairments of severe depression, particularly when it is accompanied by retardation where even the most basic of mental tasks (e.g. getting a few words out) is difficult. The distractibility of mania also precludes clear and effective thinking. However, when there has been a good recovery from mania and depression, is there any cognitive impairment still present? At first sight there is not, but when detailed tests of intellectual function are undertaken then abnormalities emerge. Bipolars as a group do not have the severe impairments that those with schizophrenia show but they still do not equate to normal controls. It may be that this is part of the explanation for why those with manic depression often do not seem to be doing as well at work as would be expected even though they have made a good recovery in terms of being free of manic or depressive symptoms.

6.5 Do complementary treatments have a place?

Where the line between mainstream and complementary treatment is drawn is uncertain. We are still not sure what forms of ‘talking’ therapies are effective (see Qs 3.20 and 5.46) and many people find less specialist forms of talking useful, from non-directive counselling to assertiveness training and anger management.

Alternative medicines: There are really no good data to guide advice on alternative drugs or foods in bipolar illness, but it is inevitable that some patients are taking them as the market is huge. Often the treatments that are used in depression such as St John’s wort are tried in manic depression. St John’s wort has been shown to be of benefit in mild depression and so it seems likely that it would also help bipolar depression, but like other antidepressants it may also have the propensity to destabilise bipolar disorder (see Table 3.2). There are also concerns that there can be interactions with other drugs, and so if St John’s wort is being taken it should probably not be mixed with mainstream drugs. It is difficult to give advice on other herbs apart from exercising caution.

Alternative medicines: There are really no good data to guide advice on alternative drugs or foods in bipolar illness, but it is inevitable that some patients are taking them as the market is huge. Often the treatments that are used in depression such as St John’s wort are tried in manic depression. St John’s wort has been shown to be of benefit in mild depression and so it seems likely that it would also help bipolar depression, but like other antidepressants it may also have the propensity to destabilise bipolar disorder (see Table 3.2). There are also concerns that there can be interactions with other drugs, and so if St John’s wort is being taken it should probably not be mixed with mainstream drugs. It is difficult to give advice on other herbs apart from exercising caution. Vitamins and minerals: Vitamins and other mineral supplements are also popular but should not be seen as a substitute for a healthy diet. However, some bipolar patients with a severe and chronic illness can become malnourished and taking multivitamins would seem sensible. Those who also have complicating alcohol problems may well benefit from B vitamins.

Vitamins and minerals: Vitamins and other mineral supplements are also popular but should not be seen as a substitute for a healthy diet. However, some bipolar patients with a severe and chronic illness can become malnourished and taking multivitamins would seem sensible. Those who also have complicating alcohol problems may well benefit from B vitamins. Omega 3 fatty acids: Omega 3 fatty acids, usually found in fish oil, are popular for both rheumatological and psychiatric disorders and there have been some encouraging trials in manic depression (Stoll et al 1999). The doses recommended in the clinical trials have been high and most readily available preparations will not provide these high levels. These may well become mainstream treatments in the future.

Omega 3 fatty acids: Omega 3 fatty acids, usually found in fish oil, are popular for both rheumatological and psychiatric disorders and there have been some encouraging trials in manic depression (Stoll et al 1999). The doses recommended in the clinical trials have been high and most readily available preparations will not provide these high levels. These may well become mainstream treatments in the future.6.6 How does the stigmatisation of mental illness affect manic depressives?

There are also some rather paradoxical ideas–for example thinking that depression is a sign of weakness and that people should just ‘pull themselves together’ while at the same time thinking that nothing can be done to improve mental illnesses and therefore it will permanent. These views are so common and pervasive that many people with the illness will also share those ideas and so not think that it is worth bothering trying to get some help or treatment (see also Q 5.44).

The other view that people who have bipolar illness commonly hear is–‘You don’t seem like the type of person to suffer from depression’–which chimes with the idea that only certain people can experience mental illness (see Q 1.18).

CASE VIGNETTE 6.1 TACKLING STIGMA

CASE VIGNETTE 6.1 TACKLING STIGMA

He developed his career after the War, particularly as the writer of The Goon Show in the 1950s. He seemed to do this in a frenzy of activity with at times very little sleep in an intense and highly productive 6 years. Towards the end of this time he was probably manic but he collapsed into depression and was admitted to hospital.

He died in 2002, and the epitaph he chose for his gravestone reads: ‘I told you I was illRsquo;.

6.7 Should patients be given drug holidays?

![]() Several people have suggested that taking a break from medication might be a good strategy as it could minimise any long-term ill effects of the treatment and stop the beneficial effect wearing off. This may have some intuitive appeal as an idea but is in practice very likely to lead to more relapses and a worse outcome (see Case vignette 5.2) and following this line should be strongly discouraged. In particular nobody should stop lithium suddenly as there is a very high chance of relapse into mania (see Q 5.27).

Several people have suggested that taking a break from medication might be a good strategy as it could minimise any long-term ill effects of the treatment and stop the beneficial effect wearing off. This may have some intuitive appeal as an idea but is in practice very likely to lead to more relapses and a worse outcome (see Case vignette 5.2) and following this line should be strongly discouraged. In particular nobody should stop lithium suddenly as there is a very high chance of relapse into mania (see Q 5.27).

There are particular problems with treating patients with antipsychotics in the long term in that there is a substantial risk of tardive dyskinesia (abnormal involuntary movements which are usually permanent). However, if this type of treatment is needed in the long term then, rather than giving drug holidays, consideration should be given to using the newer atypical antipsychotics which have a lower risk of this disorder developing (see Q 5.41).

6.8 What is the future direction for treatments for manic depression?

The sad truth is that we are not using the treatments that we have at the moment to best effect. This is most apparent in the research that has looked at suicide in bipolar patients (Isometsa et al 1994, Schou 1998). Most bipolars who kill themselves have either not been prescribed appropriate long-term treatment or have not been taking it.

6.9 What is self-management?

The term ‘self-management’ has been used by the Manic Depression Fellowship (MDF, see Appendix 1) for this process of gaining more control over the condition. The MDF is a national self-help organisation in the UK. They promote this process of taking more responsibility for one’s own condition through literature, self-help groups and a national training course.

There are a number of elements in self-management:

6.10 What is the interaction between the medications used in treating bipolar illness and alcohol?

![]() Many of the drugs used to treat bipolar disorder have sedative effects; this is true not only of the antipsychotics and benzodiazepines but also the anticonvulsants, particularly carbamazepine. Alcohol tends to enhance these sedative effects and can also exaggerate other CNS side-effects, such as ataxia. There is no direct interaction with lithium unless alcohol is drunk to the level of causing dehydration which can raise lithium levels.

Many of the drugs used to treat bipolar disorder have sedative effects; this is true not only of the antipsychotics and benzodiazepines but also the anticonvulsants, particularly carbamazepine. Alcohol tends to enhance these sedative effects and can also exaggerate other CNS side-effects, such as ataxia. There is no direct interaction with lithium unless alcohol is drunk to the level of causing dehydration which can raise lithium levels.

6.11 What is the effect of bipolar illness on work?

Those who are acutely ill with depression or mania will usually be too disabled to work, either because their concentration and attention are not sufficient or their judgement is poor. In the longer run it is disappointing to see that only about a quarter of manic depressives seem to be able to maintain work at a level at which their qualifications and experience would suggest they are capable. The reasons for this include the direct effects of the illness on the ability to work and the attitude of others. The disruptions that acute episodes of illness can cause are the most obvious effect. Manic episodes that involve embarrassing and irresponsible behaviour can prove very disruptive to working relationships that thrive on trust. Even after recovery from an acute episode low level depressive symptoms are common and this can impact on the motivation and innovation that productive work requires. Some people have mild cognitive deficits which prevent them performing at the level that would be expected, even if they have apparently made a good recovery from their mood symptoms. Many patients feel that the medications they are taking are affecting their cognitive ability or their enthusiasm or creativity. These are aspects of medication that are not well described or investigated and it is very difficult to disentangle effects of medications from long-term symptoms.

6.12 What are the rules on driving?

Driving can be such an important part of life, particularly for those who live in more rural areas where public transport is limited, that doctors are loath to prevent driving. However, this needs to be balanced by the risks that driving entails. Patients are far more likely to injure themselves or someone else in the course of their driving than they are because of direct violence.

6.13 Are manic depressives more creative than other people?

On the other hand, the sad truth is that most people who suffer from manic depression have their creativity badly stifled by the illness so that productive work and family life are curtailed because of the disruption of the illness. Creative people come in all different shapes, sizes and temperaments and it is doubtful that there is anything inherent in manic depression that makes people more creative than others. There is some evidence suggesting that those who are close relatives of someone with manic depression tend to be more successful in their careers than the average. However, it is always difficult to interpret these studies because they can be very selective in which families are investigated.

6.14 What are the issues around manic depression and contraception?

![]() The most important issue is to ensure that women who are taking treatments for their bipolar illness are also taking adequate contraceptive measures. All these drugs are potentially teratogenic and some–particularly lithium, valproate and carbamazepine–have very substantial risks to the foetus (see Q. 5.22).

The most important issue is to ensure that women who are taking treatments for their bipolar illness are also taking adequate contraceptive measures. All these drugs are potentially teratogenic and some–particularly lithium, valproate and carbamazepine–have very substantial risks to the foetus (see Q. 5.22).

6.15 What advice should be given to a woman with manic depression who wants to have a baby?

There are two main aspects to this advice:

Women remain at risk of suffering acute episodes of mania or depression during pregnancy though the risk may be slightly reduced when compared to other times. However, the reduction in risk is small and it should not be assumed that pregnancy is protective against manic depression. On the other hand, the risk of relapse (particularly of manic relapse after childbirth) is very high, perhaps eight times the risk of any other month. Most women with manic depressive illness will need to take some preventive medication during pregnancy. Only those who have infrequent episodes are likely to get through pregnancy without a relapse and without medication.

Valproate and carbamazepine are associated with neural tube defects in about 1% of births. Valproate is slightly more dangerous than carbamazepine. It may be that taking folate can mitigate this risk and this is advised prior to and during pregnancy. Antidepressants and antipsychotic drugs, particularly the older ones, are of less risk to the foetus, though there are now reassuring data that fluoxetine is also a lower risk treatment (see www.ncl.ac.uk/pharmsc/entis.htm).

The safest tactic is to try to reduce and stop the medication prior to pregnancy. This is not always easy and the situation often arises of trying to take a woman slowly off preventive medication in order for her to become pregnant only to find that she relapses each time and has to restart treatment.

6.18 What is puerperal psychosis?

CASE VIGNETTE 6.2 RECOGNISING PUERPERAL PSYCHOSIS

CASE VIGNETTE 6.2 RECOGNISING PUERPERAL PSYCHOSIS

Alice has now not slept for three nights and ‘doesn’t seem to know what’s going on’. She phoned her mother to come and help but called her a ‘fucking bitch’ when she arrived. The midwife returned to find that Charlotte was half naked in the kitchen saying that someone had been banging on the back door demanding sex.

6.19 Can women breast feed if they are taking medications for bipolar disorder?

146If the mother is taking lithium then it is likely that the baby will have substantial lithium blood levels and may suffer toxicity, so breast feeding should be strongly discouraged (see Q. 5.24). The advice on valproate and carbamazepine is less clear and probably only small amounts get into the baby, though this can still cause problems (e.g. developing a drug-related rash).

6.20 What is different about treating adolescents with bipolar disorder?

Diagnosis can be a difficult issue in this age group. There are a lot of other changes going on for teenagers and irritability is commonly seen. There is a natural reluctance to give a mental illness diagnosis and pursue a line of medication use unless you are sure that this is correct. Adolescents have the same symptoms as adults although adolescents may be more likely to have psychotic ideas and mixed affective states (see Q 1.11).

Illicit drug use is common among those in their teens and twenties and more common among those who have a mental illness. This can not only affect the course of the illness but also lead to other health and sometimes legal problems (Case vignette 6.3).

CASE VIGNETTE 6.3 DRUG USE AND NON-COMPLIANCE CAN BE SERIOUS COMPLICATIONS FOR ADOLESCENTS

CASE VIGNETTE 6.3 DRUG USE AND NON-COMPLIANCE CAN BE SERIOUS COMPLICATIONS FOR ADOLESCENTS

Over the next 3 years she had three further admissions and on each occasion she was both elated and irritable, as well as being overactive, aggressive and paranoid. Though she made a good recovery at each admission and managed to get back to college (they were particularly indulgent of her illness as she had a considerable artistic talent) she continued to smoke cannabis regularly and did not take any medication unless strongly encouraged by her parents. She also continued to have some unusual ideas about the way that television programmes would mention her name in obscure ways and had made a compilation video tape of these, which no-one else found very convincing (see also Q 1.15).

6.21 How should anxiety be treated in someone with a bipolar illness?

However, others experience marked anxiety but do not have prominent depressive symptoms and the anxiety needs to be treated in its own right. A first step is to look at lifestyle factors, particularly the use of alcohol and caffeine. On the medication front antidepressants are usually the treatments of choice for anxiety disorders but the risk of precipitating mania should always be borne in mind (see Q 3.15). Benzodiazepines are effective anxiolytics in the short term but the risks of tolerance and dependence mean that these treatments should be used for a few weeks at the most.

6.22 Do people with manic depression have evidence of brain damage?

Many people with manic depression and their families ask that their brain be scanned to see if there is any abnormality. Many psychiatrists will perform brain scans particularly of new patients with manic depression to make sure that there is no organic abnormality but the pick-up of identifiable lesions is low and that of remediable lesions is even lower.

6.23 What is the treatment for rapid cycling?

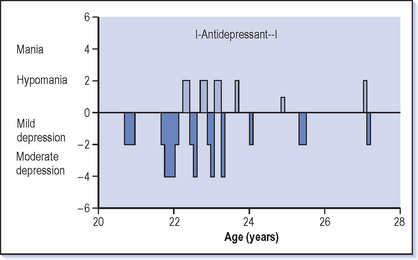

Taking antidepressants is strongly associated with rapid cycling (Fig. 6.1) and the best line of treatment is to stop the antidepressant. There is also a connection associated with thyroid dysfunction and this should be checked as well.

6.25 How should alcohol problems in bipolars be treated?

STAGES OF MANAGEMENT

The first stage of management is recognition; it is easy to overlook alcohol problems when you are focused on serious mood disturbance but this should be borne in mind with all bipolars because excessive drinking is so common.

TREATMENT

Encourage a trial of abstinence to see how this affects the mood. This only requires patients to commit to a short-term change and there is a fair chance that, contrary to their expectations, their mood actually improves and they gain more stability. This will hopefully show that the alcohol is actually worsening their mood in the longer term, even though they find it gives relief in the hours after they take it. Alternatively, the medication may prove more effective when the effect of alcohol is removed. It is often also said that alcohol prevents antidepressants working properly. It is certainly true that giving up alcohol in itself has a beneficial effect on depression.

Encourage a trial of abstinence to see how this affects the mood. This only requires patients to commit to a short-term change and there is a fair chance that, contrary to their expectations, their mood actually improves and they gain more stability. This will hopefully show that the alcohol is actually worsening their mood in the longer term, even though they find it gives relief in the hours after they take it. Alternatively, the medication may prove more effective when the effect of alcohol is removed. It is often also said that alcohol prevents antidepressants working properly. It is certainly true that giving up alcohol in itself has a beneficial effect on depression. Maximise the benefits that can be obtained from the treatments for the bipolar illness, particularly the longer term preventive treatments, but commonly also treating low grade depressive symptoms. This is an appealing strategy, especially if it means that the patient does not need to reduce their drinking; however it is rarely successful unless attempts to reduce the drinking are also made.

Maximise the benefits that can be obtained from the treatments for the bipolar illness, particularly the longer term preventive treatments, but commonly also treating low grade depressive symptoms. This is an appealing strategy, especially if it means that the patient does not need to reduce their drinking; however it is rarely successful unless attempts to reduce the drinking are also made.6.26 How should drug misuse in a bipolar patient be managed?

TREATMENT

Encourage a trial of abstinence to see how this affects the mood. There is a fair chance that, contrary to patients’ expectations, abstinence actually improves mood and they gain more stability. This may be because the drug is actually worsening the mood in the longer term, even though they find it gives relief in the hours after they take it. Alternatively, the medication may prove more effective when the effect of the drugs is removed.

Encourage a trial of abstinence to see how this affects the mood. There is a fair chance that, contrary to patients’ expectations, abstinence actually improves mood and they gain more stability. This may be because the drug is actually worsening the mood in the longer term, even though they find it gives relief in the hours after they take it. Alternatively, the medication may prove more effective when the effect of the drugs is removed. Maximise the benefits that can be obtained from the treatments for the bipolar illness, particularly the longer term preventive treatments, but commonly also treating low grade depressive symptoms. However, as with alcohol, response to treatment is often poor when the drug misuse continues.

Maximise the benefits that can be obtained from the treatments for the bipolar illness, particularly the longer term preventive treatments, but commonly also treating low grade depressive symptoms. However, as with alcohol, response to treatment is often poor when the drug misuse continues.6.27 Is it safe for me to have a baby?

Pregnancy does not protect you from suffering a relapse of your bipolar illness, though the chance of this may be a bit lower. This means that most women with manic depressive illness need to take some preventive medication during pregnancy if they are going to stay well. There are some risks to the baby from you taking medicines, particularly in the first few months of pregnancy. In fact the highest risk time is the first few weeks when you may not even know that you are pregnant. That is why it is important to plan this before you get pregnant, and also when you are taking treatments that you take good contraceptive measures (see Q. 6.14).

6.31 What should I tell my employer or put on a job application form?

This depends on the employer! The general advice about filling in application forms is not to write manic depression on the initial form. These forms are generally only seen by lay people who have very little understanding of the illness and so the stigma of the illness is likely to lead rapidly to rejection rather than a reasonable assessment of your abilities. On the other hand it is important to let employers know that you have been ill and what the possibility is that you might become ill again. One suggestion is to put on an initial form that you have suffered from depression and are taking medication and only go into further details when you are dealing with a doctor or nurse who is assessing your occupational fitness. Obviously with small firms there is not the same occupational health back-up and so you need to have a discussion at some point with your potential employer about your illness. In the end honesty is usually the best policy, though being cautious about how much you reveal may prove more useful in the beginning! Talking to others who have been in the same position (e.g. in groups like the Manic Depression Fellowship, see Appendix 1) is often the best way of generating ideas for dealing with this difficult area.